Full Court Press

Uyghur Muslims in America turn to activism—putting pressure on the NBA and its sponsors—to help their fellow Uyghurs in China

The NBA season starts next Tuesday, and while basketball faces declining TV ratings domestically, it remains popular in China, where stateside games have been broadcast for 35 years. Fewer basketball fans at home are only one problem plaguing the league, however. NBA players, officials, and executives are frequently accused of catering to their (larger) Chinese market, while downplaying China’s human rights abuses. In particular, the NBA and its sponsors, including sports retailers like Nike, have been both directly and indirectly implicated in the Chinese government’s ongoing campaign against the ethnoreligious minority Uyghur Muslims in China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR). Abuses there include forced sterilization, slave labor, and internment camps. But the NBA and its sponsors are hardly the only high-profile American corporations to have unsavory ties to the abuses in the XUAR. That is why in December of last year, the Biden administration signed into law the bipartisan Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA), intended to take practical steps to sever the Gordian knot of soft power competition and economic interest that, along with Chinese Communist Party bigotry, binds Uyghur Muslims, even in the U.S.

Before it was the XUAR, the region in northwest China was known as East Turkestan, home to the Turkic-speaking Central Asian Uyghurs. Uyghurs converted to Islam in the 10th century CE, prior to which they practiced a mélange of Christianity, Buddhism, and Manichaeism. The Encyclopaedia Britannica says Uyghurs appear in Chinese historic records as far back as the third century CE, settling around western China’s Tien Shan mountains in the ninth century. The CIA World Factbook estimates that nearly 2% of China’s 1.4 billion strong population is Muslim; that’s around 25 million people, more Muslims than there are in Syria.

Tensions with the ethnic Han Chinese, who began moving to the XUAR in the mid-20th century, became more intense and frequent over the decades. And while the current CCP campaign of ethnic assimilation directed against the Uyghurs has garnered international attention recently, official Chinese persecution against Uyghurs is nothing new, according to Uyghur American Nury Turkel, chair of the U.S. Commmission on International Religious Freedom and Hudson Institute senior fellow.

“The Uyghur people have been subject to all forms of persecution, [to] rights violation, as long as I can remember,” Turkel said. He cites the Uyghurs’ ethnicity and religious background as reasons for official persecution in China, with the methods and justifications changing with the times. “Historically, they went after Uyghurs who have separatist tendencies. Not action. Tendencies. So they were able to measure who had tendencies demanding a separate Uyghur state.” This, he said, was the case in the 1980s and ‘90s. “And then after 9/11, they used counterterrorism, because of the U.S.-led war on terrorism.” Even now, Turkel said, it ostensibly “still is the case that they’re fighting against terrorism.” Combatting terror is only the most recent justification for suppression of Uyghurs, he said, with the Chinese government taking “a different direction” with regard to their methods around 2009 and 2010. They gave up on the carrot-and-stick approach, said Turkel, which allowed “those who are compliant, submissive, just to go about their lives: practice state-sanctioned religion, participate in some cultural affairs.” It was when Xi Jinping took office, he said, that “this turned into [a] full-swing racist campaign.”

“‘To clear out the weeds by chemical,’” Turkel said, paraphrasing a quote attributed to a government official about the government’s anti-Uyghur methods. “So, to the Chinese regime, specifically Xi Jinping’s China, Uyghurs’ ethnonational identity would pose a political threat, as long as they maintain that distinct ethnoreligious identity, way of life, and culture.” For the CCP, “all foreign religion, specifically Christianity and Islam, pose an existential threat. Because these two religions [are] not only foreign,” Turkel said. “It’s Western religion to them. Because they understand all the Abrahamic religions [believe] in individual liberties. You know, the things that we cherish and value in the United States, things such as free speech, free press, freedom of religion. They lump all this together in their constant battle against Western ideology. Any organized religion, or any religious teacher, preacher who preaches religion, goes in the face of the Communist ideology. The Chinese already know that religious freedom or religious belief and Communist ideology are incompatible.”

Despite being Sunni, like the majority of Muslims globally, Uyghur Muslims do not receive much attention from the wider Islamic world, said Turkel. Domestically, he said, the U.S. Muslim community “has been selectively very supportive” of Uyghur Muslims. He said one reason for this could be the position of other U.S. Muslims’ countries of origin vis-a-vis China. “Even if you’re an American citizen, if you do too much of anti-China activity, your country can still go after you,” he said. “What we’re dealing with is not kind of a Jeffersonian democracy.”

Internationally, Uyghur Muslims who make it to Saudi Arabia, for example, can still face deportation back to China, in an authoritarian intimidation technique called transnational repression. According to a piece in Foreign Policy earlier this year, it is emerging as a preferred way for authoritarian governments to keep individuals and minorities in check, no matter how far they manage to run. “Exile communities cannot feel safe,” wrote author Ryhan Asat, “even after they’ve escaped to outside countries, as the practice of transnational repression proliferates without any significant response. Uyghurs are at the greatest risk since China wields significant economic and diplomatic power over the countries with the largest diaspora communities.”

“I can’t imagine [Saudi] Prince Mohammed bin Salman would come out and criticize his friend Xi Jinping,” Turkel said, “It’s not going to happen. I can’t imagine countries like Pakistan or Iran coming out in defense of the United States’ sympathetic approach to the Uyghur crisis.” On the other hand, Turkel said he wonders at the relative silence of the academic communities and other faith communities in the U.S. and abroad. “I can’t imagine any country locks up a million-plus members of its Muslim community, we will be seeing this kind of silence,” he said.

If it is risky for many non-Uyghur Muslims to speak out, the danger is that much more immediate for Uyghurs themselves. According to Uyghur American Association (UAA) President Elfidar Iltebir, Uyghurs first began arriving in the U.S. for graduate degrees and Ph.D.s prior to the organization’s founding in 1998. Iltebir says ethnic riots between Han Chinese and Uyghurs in the city of Urumqi in 2009 caused younger Uyghurs to begin emigrating to the U.S. in larger numbers to finish their educations abroad. Today the UAA estimates there are between 8,000 and 10,000 Uyghurs living in the U.S., with many living in the Washington, D.C., area. Turkel describes the D.C. Uyghur community as tightknit. “But the vast majority of Uyghurs are not public, you know,” Turkel said. “They cannot go out and speak out against [the Chinese government], because [it has] been very effective in its efforts to silence the Uyghur American community.” Even those with U.S. citizenship cannot speak out on behalf of missing friends and family members for fear of reprisal.

If it is risky for many non-Uyghur Muslims to speak out, the danger is that much more immediate for Uyghurs themselves.

The Uyghur American experience, as Iltebir describes it, is inextricable from the Uyghur experience in China, characterized by constant anxiety for friends and family who remain in the XUAR and fear of transnational repression. “They’re even afraid to ask, ‘where’s my family?’” she said, because the price of speaking up—state retaliation against loved ones still within the XUAR—is deemed too costly.

This, Iltebir said, leads to survivor guilt among those living in the U.S. Here, she said, “they are just dying quietly.”

However, guilt is not the same thing as despair, and silence is not the same thing as inaction. Iltebir said that while the UAA was initially founded primarily to preserve cultural traditions, in recent years, it has transitioned to advocacy and activism for parents and siblings in concentration and forced labor camps overseas. She said that the UAA also helps Uyghurs in the U.S. apply for asylum and to access services and resources. Last month, the organization staged a protest in front of the Chinese Embassy in Washington, D.C., to protest the extreme COVID-19 lockdowns they say that Uyghur Muslims are experiencing in their home region, confined to their homes without access to food or other essentials. The UAA was also present at the 59th convention of the Islamic Society of North America last month, with Uyghur Americans speaking to attendees there of siblings in Chinese concentration camps, and of how Islamophobia drives Uyghur oppression in China.

“Because of our faith, we are being oppressed,” Iltebir said. “So that’s why we like to get the relationship with faith groups.” She said that some attendees weren’t fully aware of the situation with the Uyghurs in the XUAR, but, she said, given the preponderance of evidence of systemic abuse of Uyghur Muslims there, “once they know, they do support.” And while she sees Americans as a whole waking up to the issue, she feels there is a disparity between what the general public knows, and the familiarity of academic and political elites with the subject. For that, Iltebir credits the activism of the UAA and others who worked to inform U.S. lawmakers about the events in the XUAR, which she believes influenced the passage of legislation intended to target the Chinese government’s treatment of Uyghurs. However, she echoes Turkel’s disappointment with other Muslim countries’ unwillingness to follow suit.

“Sometimes I hear that some of the—especially the Muslim countries—other countries say this is U.S. propaganda,” Iltebir said. She is careful to draw distinctions between the citizens of these countries and their leaders, who, she said, “are silenced by the economic incentives given by the Chinese government.”

Amid these challenges, Uyghur Muslims in the U.S. remain committed to their faith and to their cultural identity. In 2021, for example, D.C.-area Uyghur Americans founded the Uyghur Islamic Center to meet for prayer and cultural activities. Meanwhile the Boston Uyghur Association website offers a variety of religious, cultural, and language resources to what it says is a local population of around 200 Uyghurs, as well as free legal assistance for refugees and asylum seekers.

The UFLPA’s intent is to break up the complex network of supply chains by which goods produced by Uyghur slave labor enter U.S. markets. “We do not want to purchase products made by Uyghur forced labor,” said Iltebir. “It may be made by my cousin or my friend.” As a result, she said, seeing corporations like Nike and others “selling the products that are linked to Uyghur forced labor really disappoints us.”

The discrepancy between corporate America’s stated commitment to equality and justice, and their dependence on unethically manufactured products, dates back two decades, to the end of the Clinton administration, and the establishment of “permanent normal trade relations” with China. It was an end-of-history, pre-9/11 pledge of good faith in the coming global harmony of interdependent economies and markets. After all, no two countries with a McDonald’s had ever gone to war with one another.

In a 2019 National Affairs op-ed titled “Shock Therapy,” Niskanen Center director of poverty and welfare policy Samuel Hammond put forward a grand theory of how permanent normal trade relations between China and the U.S. affected the cultural and economic shift we are currently living through in America, in which he says corporations pay lip service to social justice, while ignoring the injustices in which they themselves are complicit. If Hammond’s thesis is broadly correct, it might go some way toward explaining why, for example, despite its vocal positions on domestic cultural issues, Nike was one of the corporations lobbying lawmakers to tone down the provisions of the UFLPA, which holds corporations responsible for identifying forced labor in their supply chains, and which prohibits imports from the XUAR.

Hammond said in his article that in normalizing trade relations with China, the U.S. was operating from the economic theory of comparative advantage, or the idea that when two countries engage in free trade, each is freed up to focus on the areas of production in which they excel. What it actually meant, he said, is that the U.S. developed into a knowledge economy, which prioritized (and rewarded with higher wages) highly skilled workers with advanced degrees, and accordingly outsourced or automated labor-intensive manufacturing jobs. But China, according to Hammond, did not behave the way conventional macroeconomic wisdom said they would: contenting themselves simply with low-skill manufacturing. Rather, China got busy investing in the diversification of its export production. The result was the U.S. importing more, cheaper goods, the stagnation of wages among U.S. workers with fewer academic bona fides, and the decimation of low-skill jobs in rural America. Hammond describes a cycle of lopsided co-dependency, in which the U.S. laptop class produces IP that is then manufactured in China by workers who are more proficient with highly technical manufacturing processes (he cites the copy on a new iPhone box: “Designed by Apple in California/Assembled in China”). He said the result was a rapidly deindustrialized rural America alienated from an urban progressive elite that had more disposable income. Corporations, Hammond wrote, recognized this reality, and catered to the latter’s tastes and worldview. “Republicans buy sneakers, too,” Michael Jordan once famously said in jest, about why he didn’t speak out on politics. However, today the company that traded on Jordan’s iconic status to become a titan of the basketball shoe market beginning in the mid-1980s, does not share his political agnosticism. In recent years, Nike has taken public stands on a range of progressive political issues. “The Twitter left’s problem with Nike,” Hammond wrote in his op-ed, “is not that they employ sweatshop labor, but that they would design a sneaker with the Betsy Ross flag,” a purportedly white supremacist dog whistle.

It’s our brothers and sisters who are working in those forced labor camps.

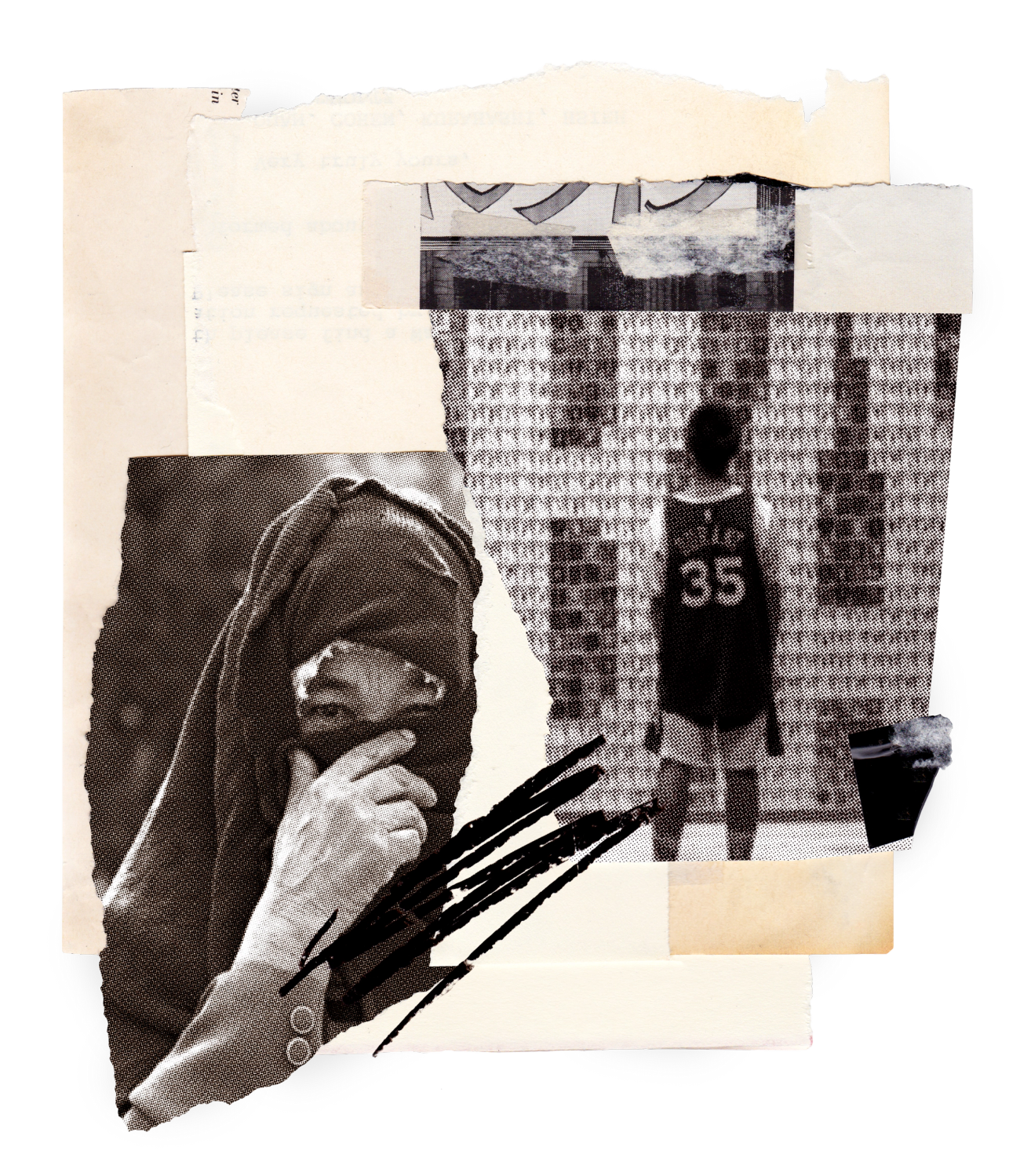

“To me,” Turkel said, “even to this day, LeBron James, people like LeBron James, do the bidding for Communist China.” Like Hammond, Turkel detects a mismatch between the values the players espouse domestically with what they are willing to tolerate abroad. “So instead of influencing the leaders in a repressive society in an authoritarian regime, the American athletes are adopting something that they despise based on their public statements,” he said, “so that those people who are protesting against our government, against certain issues in our society, are not willing to even call out the Chinese.”

After Houston Rockets’ general manager Daryl Morey tweeted in support of Hong Kong democracy protesters in October 2019, his team owner and other NBA officials distanced themselves from the sentiment. James, in China with the LA Lakers for some exhibition games at the time, refrained from taking a position while overseas. Upon returning to the U.S., James insinuated that Morey, who had tweeted “Fight for Freedom, Stand with Hong Kong” on Oct. 4 of that year, had been “misinformed,” or perhaps not fully educated on events there. Morey’s tweet led to the Chinese government pulling NBA games from the air and Chinese companies pulling sponsorships. NBA broadcasts resumed in the country earlier this year.

James is one of Nike’s most outspoken sponsored athletes on race relations, and arguably its most high profile. In 2016, James signed a lifetime deal with Nike, a partnership worth $30 million annually. Four years later, in 2020, Uyghur forced labor was found to be used in assembling Nike products in China.

“Sponsors like Nike,” said Turkel, “also sponsored the [2022 Winter] Olympics. And to this day, none of the U.S. companies that are implicated in the slave labor practices has said even anything remotely close to the fact that there’s human rights abuses in China.” Turkel points to Beijing Olympic sponsor Coca-Cola, which publicly criticized 2021 Georgia voter access legislation, but declined to mention abuses against the Uyghurs in China by name during a 2021 congressional hearing on the subject with other Olympic sponsors.

And the Nike story wasn’t the only one linking U.S. basketball to China’s treatment of Uyghur Muslims. That same year, news broke that the NBA operated training camps for young people inside the XUAR, intended to identify upcoming international talent. Accounts emerged of the physical abuse of the young players (predominantly Uyghur, according to ESPN reporting) and surveillance and harassment of the American coaches and staff.

Of course, sports isn’t the only thing linking the U.S. economy to China, or specifically to the XUAR, which produces much of the world’s cotton. Turkel said the U.S. policy of climate cooperation with China contributes to problems in the region. Although climate talks between the U.S. and Beijing are stalled as of this writing, in response to House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s recent Taiwan visit, Xinjiang has been reported as a known link in the electric car battery supply chain. The XUAR is also critical in solar panel manufacturing. However, the UFLPA’s impact will have ripple effects, given that other parts of China manufacture with raw materials from the area. Under the new law, which went into effect this year, U.S. companies are now responsible for providing U.S. Customs and Border Protection with detailed maps of their supply chains and proof of good working conditions.

But sports remains a visible flashpoint, with regard not only to U.S. basketball, but internationally, as well. Turkel publicly advocated against U.S. participation in what he calls the “genocide Olympics,” the Winter Olympic games held in China earlier this year. He points to the way the Olympics helped normalize Hitler’s regime in 1936, and to the Russian invasions of Georgia and Crimea after the 2008 and 2014 Summer and Winter Olympics, respectively, to demonstrate how sports coverage can soften and obscure the truth about a regime. “We should not,” he said, “let the CCP use this friendship-purpose event to normalize their behavior: setting up concentration camps at the industrial scale, committing genocide against ethnoreligious groups, daily threatening Taiwan, upending Hong Kong democracy, and engaging in very aggressive forms of coercive diplomacy around the world.” The diplomatic boycott of this year’s Winter Olympics wasn’t enough in Turkel’s estimation, and he said it remains important to “shine a spotlight on the U.S. sports world’s complicity in the ongoing crime committed against Uyghurs.” The overseas training academies and what Turkel calls “the Houston Rockets episode,” are in his opinion, “more than tone deaf.”

Turkel is hopeful that the UFLPA going into effect will start to disentangle the business of U.S. sports from its problematic associations with human rights abuses in China (although he pointed out that Brooklyn Nets owner Joseph “Joe” Tsai is also the owner of Chinese juggernaut online retailer Alibaba). He said he believes it is “already having an impact.” In Turkel’s view, this is because the ball is now in the court of corporations, rather than of U.S. taxpayers, making the former responsible for investigating and policing themselves to ensure that their products are not manufactured using slave labor. “I think that’s the brilliance of this law,” he said, “essentially telling them, ‘We believe everything that you bring to the United States is made by slave labor, unless you can prove with evidence.’” It is in companies’ best legal and financial interest to comply, he believes. “Businesses like Nike,” Turkel said, “know that this will create enormous pressure on them in China. It creates serious legal issues in the United States.” He points to a recent decrease in sales for Nike, which he argues may indicate that retailers are placing fewer orders for Nike products in light of U.S. lawmakers’ interest in forced labor practices (Nike attributes it to the effect of ongoing lockdowns in China). He also said it could reflect a backlash in China to Western concerns over Uyghur forced labor. The New York Times published an explainer last year about Chinese social media influencers encouraging Chinese consumers to boycott Western companies and to purchase Chinese brands instead.

“These businesses should know better,” Turkel said. Rather than “pressuring our Congress, pressuring the administration not to go hard on them, watering down the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, they should have used that influence that they have in China to tell the Chinese minders, the Chinese entities, the government offices, that look, if you want me to stick around this country to continue to do business, I have to do things the way that the United States wants me to do. There’s a legal risk. Instead of doing that, they pressured Congress, lobbied it, against the Forced Labor Prevention Act.”

Despite the promising initial effects of the UFLPA, there remains the harsh reality faced by Uyghurs in the XUAR, who in addition to forced internment and its accompanying abuses, also live in proximity to what satellite imagery suggests is China’s newest nuclear testing site. Even those who make it out encounter ongoing threats and hardships.

“I recently published a book, and I give my book a title, No Escape,” said Turkel, who was born in a Chinese reeducation camp during the Cultural Revolution. Despite U.S. citizenship, a senior fellowship at a think tank, and a position in the U.S. government, he said, “I don’t feel I’m free yet.”

For Turkel and Iltebir, Uyghur forced labor is not mere abstraction. “It’s our brothers and sisters who are working in those forced labor camps,” said Iltebir. “We should visit every single university, we should visit every single church, the synagogues, the mosques, to bring awareness about this Uyghur genocide.”

But money talks, goes the saying. If the richest athlete in one of the richest countries in the world is unwilling to lend his voice to the Uyghur Muslims’ cause, there is little reason for anyone else to risk theirs. As the NBA gears up for its first season since the passage of the UFLPA, it remains to be seen how far the league and its sponsors are willing to extend their stated dedication to human rights and social justice.

This story is part of a series Tablet is publishing to promote religious literacy across different religious communities, supported by a grant from the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations.

Maggie Phillips is a freelance writer and former Tablet Journalism Fellow.