My Grandmother, the Undocumented Immigrant

On a recent trip to Cuba, I learned more about my grandmother’s journey to America—and the different ways my family has interpreted that piece of our history

In our family lore, we’ve regarded my grandmother’s year in Cuba as a bit of trivia in her heroic coming-to-America story, a peculiar intermezzo between the melancholy overture of shtetl life in rural Russia and the happy-ending crescendo of her American Dream. I hadn’t given it much thought until I decided to visit Havana myself in April, accompanying my husband, who was going there for work. It seemed like a rare opportunity to witness a country that had been off-limits to Americans for so long and was now going through a historic transformation.

We began preparing for the trip last fall, reading books and articles, filling out our visa applications, and loading up on essentials that our trip leaders had suggested we take along, like over-the-counter medications or extra rolls of toilet paper, which we were warned were not easily obtainable in Cuba because of the American embargo that’s still in effect.

However, our plans were put on hold because of the November election and the uncertainty immediately afterward about the new administration’s policies on Cuban tourism.

The trip was the last thing on my mind during those heady weeks late last fall. Among my many concerns about the election’s outcome was the fact that our country, which had such a strong heritage of immigration, had elected a president who’d made it a central part of his campaign to attack immigrants and to advocate closing our borders to immigrants with and without documents.

Growing up, I was taught to revere our grandparents as heroes for the sacrifices they’d made in moving to the U.S. And yet, there were Trump supporters in my own family, which had benefited from the sacrifices made by our immigrant ancestors.

Looking for ways to channel my worries into action, I marched and donated money to pro-immigrant causes. I volunteered to teach English as a second language. I called, emailed, and visited members of Congress. And when I learned that our trip to Cuba was back on, I decided to find out more about my grandmother’s much more fraught journey from Eastern Europe to Havana almost a century ago. As much as I could, I hoped to retrace her steps, or at least to see what she might have seen as a young woman suddenly transported from the mud and snows of small-town Russia to a tropical Caribbean island.

Most of what our family knows about this story is contained in roughly 20 minutes out of hours of interviews my brothers recorded with my grandparents during the 1970s and ’80s. (In the background, you can hear my grandmother offering to distract me, then a toddler, during the boring adult proceedings.) I had listened to these tapes years ago, but as I played them again, days before my journey to Cuba, I listened with careful attention.

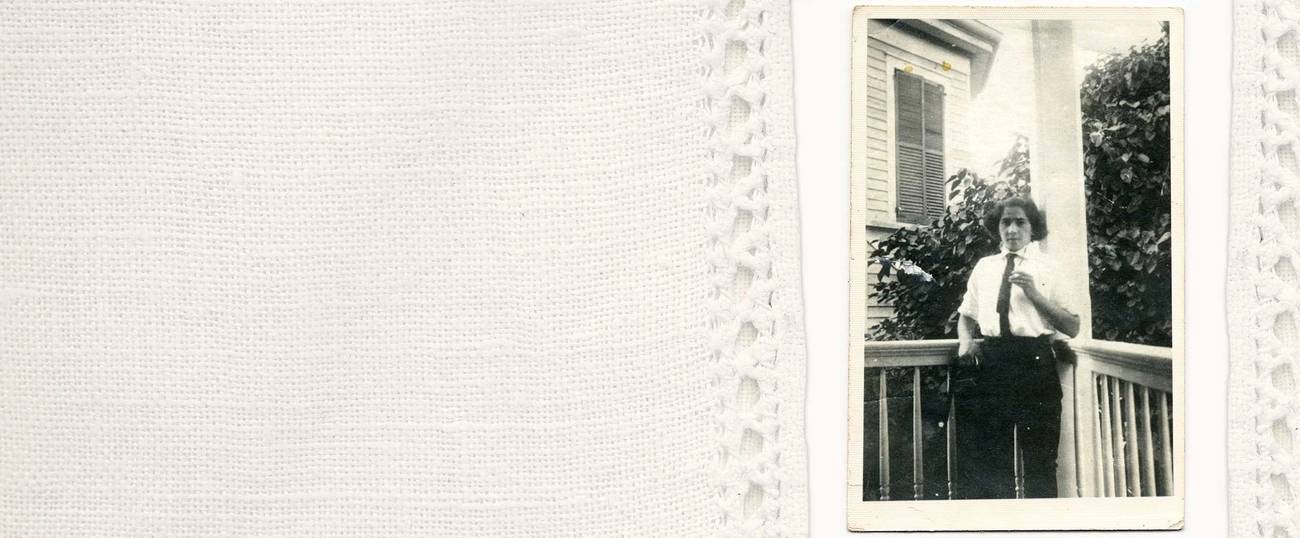

We don’t know the exact date or even the year when my grandmother Ethel Lansky—or, as we called her, “Ma”—was born in the shtetl of David-Horodok, in today’s Belarus. As the daughter of a cantor, she was relatively well-off compared with her neighbors, though she still endured poverty, anti-Semitic pogroms, and WWI. However, by 1921, the anarchy of the Russian Revolution had made life intolerable.

Seeking visas to come to America, Ma and her sister traveled to Warsaw, where they found themselves out of luck. In an atmosphere of anti-Communist and anti-Semitic hysteria, the U.S. Congress had recently passed the Emergency Quota Act, which tightened limits for immigrants from Eastern Europe, many of whom were Jewish.

But then Ma heard that if she and her sister went to Cuba, they could wait there a year before trying again for America.

On the recordings, my grandmother describes in her shaky yet emphatic voice her decision to leave behind most of her family and everything she knew for a country across the globe in three simple words. “So I vent,” she says in her thick Yiddish accent, her tone matter-of-fact.

After 20 days at sea, Ma arrived in Havana, where she received help from a Jewish immigration organization. (She claims it was HIAS, the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, but it was more likely a Cuban-Jewish group called the Ezra Society.) Eventually, she and her sister were housed with a middle-aged, childless Jewish couple. Ma, a skilled seamstress, earned her keep by making hats.

At that time, Americans often traveled to Havana as tourists on day trips back and forth from Florida. After six months, my grandmother’s sister paid one of these tourists to smuggle her into the States.

“So I thought, for another $10, I can smuggle, too,” Ma says on the recording. When she’d saved up enough money, she bribed an American couple to take her with them to Key West and pretend she was their daughter.

As she disembarked in Florida, Ma was immediately stopped by border agents and detained while they investigated her case, to see if she was involved in human trafficking. One of the officials had a Jewish name—Shulsinger—so when Ma wrote her father in Russia asking him to verify her identity, she hoped that because he was also a “Shul-singer,” she might earn better treatment.

She was detained for 10 days, then deported to Cuba without a penny to her name.

“They sent me back—and I did it again,” Ma declares defiantly.

This time, she tried a different tack. Back in Havana, my grandmother met a Jewish man who worked for the American consulate and helped her get a visa. He assured her there were no records of her recent deportation from Florida, but just to be safe, Ma entered the States via the port of New Orleans, where border controls were less strict than in Florida or New York.

I stopped the recording.

Here’s the odd thing. It wasn’t as if this information had been kept secret or that I hadn’t heard these tapes before. Yet only now, in the first hundred days of the Trump administration, did the full significance of this information hit me: My grandmother had been deported for trying to sneak across the border as an undocumented immigrant.

My first full day in Cuba, our bus dropped off our tour group in Old Havana, a bit north of the port where my grandmother would have sailed in from across the ocean. The air felt warm and heavy with humidity, and I pictured Ma stepping down from her boat, sweating in her heavy European clothes.

According to our guide, Jews from my grandmother’s time lived in this neighborhood, its narrow, crooked calles crowded with buildings in styles ranging from Spanish colonial Baroque to art deco.

In the streets where tourists tend to walk, busy with souvenir shops and women in colorful costumes who charge a few bucks to take their picture, the buildings have been lovingly restored, painted in bright pinks and blues, like frosting for birthday cakes.

But stray a block or two off this path and you encounter architecture that has crumbled to brown and gray facades, with rusted metal bars over the windows. Some buildings are merely roofless shells threaded with weeds, while a few have collapsed into rubble. I passed Cubans staring vacantly from dark, empty doorways, filling jerry cans with water from portable tanks, or filing into bodegas where they presented chits to receive government-issued subsistence rations of rice, oil, and beans.

Cuba in the 1920s wouldn’t have been much cheerier for people like Ma. In an article on the website Jewish Women’s Archive, Margalit Bejarano, author of the book The Jewish Community of Cuba: Memory and History, describes their desperate circumstances:

Immigrants were tempted to come to Cuba since travel agents promised them an easy passage from there to the United States. They found themselves without money in an unfamiliar environment, in a country stricken by economic crisis and unemployment. Jewish women from Eastern Europe were unaccustomed to the heat and to local conditions and were afraid to work in domestic service in a non-Jewish home. … They suffered from malnutrition, the difficult climate and loneliness. They crowded together in small unhealthy rooms near Havana’s red-light district, paying a monthly rent of $5 per bed…

My mother says Ma told her she had fond memories of her work in Cuba, decorating custom-ordered hats with ribbons and feathers. That may have been true. However, for others, the reality wasn’t so nice.

According to Bejarano: “Havana in the 1920s, like New York in the early 1900s, had its Jewish sweatshops, with young women employed by other Jews during long working hours, in suffocating heat, for a poor salary.”

Ma and her story kept popping up during my journey, often when I wasn’t expecting it. One afternoon, on the way to Cuba’s National Capitol Building, our guide explained the avenue where we were driving had once been lined with high-end department stores. Her grandmother, like many women in her day, would dress up to stroll along and admire window displays of beautiful clothes they could never afford. I wondered if Ma, who’d always loved fashion, had also found some solace looking at these windows.

During our group’s visit to Hemingway’s house in the suburb of San Francisco de Paula, we viewed his pleasure yacht, Pilar, and heard how he’d sail back and forth to Key West for fun, the same fateful trip my grandmother had made, most likely with her heart racing. I asked how long the ride took. “About a day,” said the docent, “but he made lots of stops.”

Another time in Old Havana, I chatted with a genial bathroom attendant who reminded me of my grandmother: that same tender smile, soft cheeks, dark, intelligent eyes. She mentioned she had a brother in Dallas. Because of my rusty Spanish, I misunderstood what she said next, so I asked if she’d enjoyed her visit there.

The woman shook her head and wagged her finger. “We can’t leave this island,” she said, still wearing her warm smile, and gripped her wrists to mimic handcuffs.

Every night, we’d return to our hotel and read the news. Much of it that week focused on the plight of Syrians caught in a civil war like the one Ma had escaped. Like my grandmother, many of them were seeking asylum in the West. And like my grandmother, many of them found doors slammed in their faces.

Yet for me, passing through immigration control in and out of Cuba was a breeze. The biggest hassle I encountered was in the Miami airport, where half of the newly installed electronic Global Entry kiosks were out of order.

Friends, acquaintances, even strangers who hear my grandmother’s story are eager to hear more. They immediately note its timeliness, given the current political debate about walls, bans, and refugees.

My family, however, has a different reaction.

Shortly after my trip to Cuba, I began recounting Ma’s Cuba story with my siblings and cousins, many of whom were unaware of it or had forgotten it (including one of my brothers who’d interviewed her for those recordings).

At our family Passover Seder, I read a selection from an alternative haggadah prepared by HIAS, focusing on our connection as descendants of immigrants with the plight of today’s refugees, who come from places like Syria or Central America instead of Eastern Europe. I noted that if our grandmother hadn’t come here, she’d likely have shared the fate of the rest of her townspeople, who were murdered by Nazi Einsatzgruppen in 1941.

“They didn’t have the State of Israel,” my brother pointed out.

“Syrian refugees don’t have the State of Israel,” I said.

“Let’s move on.”

Though Ma’s descendants all have varying views on immigration—as well as the current occupant of the White House—they share to varying degrees a general reluctance to connect Ma’s story to that debate. Again and again, I heard my family say that what happened to my grandmother belonged to a different time, that you can’t compare apples and oranges.

Two of them who are lawyers focused on some of the distinctions between immigration law then and now, while another who’s in business pointed out various economic differences. Several others told me their pro-immigrant views aren’t directly related to Ma’s history. Some simply didn’t want to discuss the issue.

My overall impression is that my family regards Ma’s story as a Jewish story rather than an immigrant story, which perhaps explains why those who support Trump see no contradiction in their love and admiration for her and their support of him. (We’ll set aside, for the sake of this argument, his relationship with the anti-Semitic alt-right.)

I hear all this, but I don’t agree, maybe in part because my vocation as a fiction writer prompts me to approach stories like Ma’s less from abstractions like identity politics or law or economics, and more from the specifics of character. As Walt Whitman said, “the particular is the only universal.”

When I try to put myself in my grandmother’s shoes, I see a desperate, fearful, yet determined young woman whose decision to cross the border illegally was animated by the same dream that motivates today’s immigrants: the hope for a better life for themselves and their children.

Perhaps the luxury of her descendants’ reluctance to identify her struggles with theirs is the ultimate proof that my grandmother’s dream came true.

Aaron Hamburger’s fourth book, Hotel Cuba, comes out from Harper Perennial in May.