A Grave Situation

At what point do our obligations to the dead give way to our own wishes?

More than a century ago, immigrants who came to America from the town of Kolomea, in Galicia, formed a brotherhood and pooled their resources—as immigrants from so many other towns in Europe had done—to buy burial plots for their townspeople. These groups kept memories of their towns alive and put their members to rest among their own for eternity. In fact, whole sections were purchased in various New York cemeteries and reserved for landsleit.

Some made use of the graves, while others either forgot about them or made other arrangements. When the brotherhood’s secretary, Aaron Hisler, passed away in the early 1970s, my father—a rabbi and also a son of Kolomea; both his parents were born there—took over as secretary. He tracked the plots and the financial transactions at multiple cemeteries.

The society’s “constitution” dating back to 1903 mandated that membership fees not exceed $3 per year. After the graves were purchased, people kept paying their dues through the 20th century. Members would receive funeral and death benefits ($10!) as well as medical treatment from the society doctor. There were many members and as was true for the early immigrants themselves, nickels and dimes for the organization accumulated. Income eventually won out over spending, and my father put the funds in high-yield bank savings accounts, a low-risk investment house, and the stock market; it grew to a much greater sum.

Over time, though, the remaining members of the brotherhood passed on. The organization was moribund yet the money was still there. My father was left with a question: What to do with the money?

After holding it in limbo for many years, Dad, who was at that point in his 80s and feeling the pressure of time, had the general sense that the money could be disbursed to charity. But he wasn’t completely sure he was permitted to do so—and if he was, could he choose which one? Or did he have to think of the preferences of the people whose money it had been, even though they were no longer here?

It was a bit of a Talmudic tangle, but also a secular/legal one: How far did he have to go to find heirs who might come out of the ether of time and space? Could he be potentially sued if heirs were to surface?

As was true my whole life, he involved me with this task, copying me on emails and correspondence. “What should we do about this?” he would ask me from time to time.

There was a blur with my father—that we were all mixed up with each other, hopelessly, haplessly even, sometimes in joy and satisfaction, often in sweet enslavement.

Straight into my 50s, he would find reasons to speak to me many times a day. Not just me but all of his children.

“I just called to say, ‘I love you.’”

I felt his sincere love and attention, but it was a kind of love that was always conscious of our roles—he, father; me, son—but in this unchanging harmony, so essential to him, our ability to grow as separate people was neglected.

In fact, when I was growing up, I could not distinguish between my father’s voice and God’s. “I am the Lord your God who has taken you out of Egypt” was the same to me as “I am your father who has given you so much.”

And now, with this task before us, how could I turn him down? I loved him, and what’s more, this was a holy task, one that involved honor and money. As usual, I gave him my completely ambivalent consent.

What to do, indeed! Of course, there was no way we were going to keep the money for ourselves. We fiddled with it this way and we fiddled with it that way. Back and forth it went.

My father had the requisite rabbinical patience for these things: endless correspondence, seemingly, endless talk in a loop: Should we give it to tzedakah—and which one? What would they have wanted? What did he want?

The thought crossed his mind: Should he get something for his troubles? He consulted lawyers, and they offered their opinions. Like the old Jewish folktales where experts from Moscow and Vienna are called in to advise, each one having an opinion, a caution. Notes were kept, copies of correspondence made, filed away. In the meantime, years passed this way, Dad in and out of hospitalizations, the scares and near misses of old age.

Yes, he was concerned his time was coming, yet he was in no hurry. It went back and forth like a pingpong ball—every few days we would talk about it on the phone. Oh, that again?

Then, Dad passed away, and now the responsibility was mine alone.

I approached this task with some irritation (why hadn’t Dad taken care of this?) and dread (would this odyssey ever end?). After a lifetime of oneness with my father—I was his companion and aide-de-camp and had done everything with him—I finally had my own life, or so I wanted to believe. But I knew I didn’t. I was still “stuck” with him, or at least with this task. It was in a sense one more errand, one more task of his that became mine.

I looked at the bank statements. The money started as a relatively modest sum; but through my father’s careful management had mushroomed into nearly $200,000.

What were my responsibilities? What did I owe these people? What did I owe him? I chafed against this “debt.” I fantasized about ignoring it or giving it to someone else to figure out. This, of course, was based on the delusion that I could finally have my own life by neglecting his work or what remained of it. That would teach him!

What claim did my father impose on me even as he was already in his grave? Is there a time that one is allowed to stop being a son?

But I could not do that. This was holy money, dead people’s money, buried if you will in the depths of common memory and benkshaft for di alte heym—a sweet if often quixotic, even romantic longing for the Old Country. And to degrade the experience through abdication or neglect would have been to bind me further to him as the “bad” or errant son. Legitimately, he had tried to dispense with it in his lifetime, but I speculated other factors deep in his personality had burdened and handicapped him.

And then a memory came to me unbidden. I was 9 or 10 years old and I had gone with him on one of his Sunday morning rounds, which often included graveside funerals and unveilings.

This was the 1970s and many of these people for whom he officiated and often eulogized were the last of the sweatshop generation. He knew their heartaches, their yearnings, their disappointments in love and labor. One always sensed that something more than themselves, something of history went down into the grave with them.

Dad’s English was perfect and his Yiddish was even more perfect. It was neither decorative nor liturgical, but the spoken Yiddish of the salt of the earth: cultural, intimate, animated, with just a touch of that old-time religion.

Unzer rabbanan hobn gelernt, a froi is getrei ir man un er shtarbt nor baym ir.

A woman is loyal to her husband and his death is felt only by her.

Upon hearing these words, the dam of pent-up tears would burst forth—first a dabbing of the eyes by the women and then guttural, heaving sobs from the men, the air now thick with Jewish regret and sorrow—as though these people, who now lived on Long Island or in Westchester had their souls cleansed because they had been to the graves and heard a Yiddish word.

After the crowd dispersed, and the clay earth freshly dug in a mound, Dad and I would sit in his big Chevy in solitude. “Fannie worked in a sweatshop with my auntie Genedl,” he told me one day of the departed, who now lay in the new grave. “You know what a sweatshop is? Der bubbe, my mother, worked in a sweatshop for 12 hours a day for seven days—all for $3 a week when she came to America.”

On that particular day, Dad made a confession: “A groyser glick, some piece of luck, my mother. She met my father. Second marriage for him, first for her. Uber zey hobn nit hobn a gefil, they didn’t have feeling for each other, but they tried to get along. Yet she bade me once, Khayim, bagrob mikh nit leben im, don’t bury me next to him.”

It was a shock, but Dad had offered me unvarnished, a precious piece of psychic reality. Zey hobn nit hobn a gefil—his parents, my grandparents, didn’t have feeling for each other. And now they lay next to each other in eternal ambivalence!

“Of course,” he rationalized, “khob nisht gehat kein braira, what choice did I have? The plots were paid for. Besides, people are in a mood, they say things, they struggle with each other. You’ll see when you get older. Bai tag zum get, bei nakht zum bet. During the day, they quarrel, but at night they forget all about it and sleep next to each other.”

This confession, this revelation was quickly repressed—buried really, by both of us—until now.

Although these two things—the money entrusted to him and the burial plot for my grandparents—were very different, this piece of memory that parachuted back into my consciousness was an odd gift. It was an insight into my father’s personality. That Sunday morning all those decades ago, in his dissociated admission, he was negotiating his guilt in relation to an odd claim from his mother: bagrob mikh nit leben im, don’t bury us together.

What were my responsibilities? What did I owe these people? What did I owe him?

When I studied psychoanalysis, I learned that an aspect of love is about people being open to each other’s projections and claims. I received his (he projected onto me the idea that I was a “great” son) and he received mine (that he was a great and powerful dad). What’s more is that a good rabbi (and a good psychoanalyst) makes himself available to people’s fantasies as well. They may be outlandish, but in love, we contemplate even the most preposterous of claims.

I began to consider: What claim did these people have who had asked my father for help? They had wanted graves but they hadn’t needed them after all. And what kind of claim did my father imagine was made on him when his mother said, don’t bury us together—was she being serious?

And what claim did my father impose on me even as he was already in his grave?

Is there a time that one is allowed to stop being a son?

And still the question pressed on: What to do with the money?

I consulted a cadre of rabbis, men of learning and substance. Yet each of them independently referred me to the same person. That was uncanny enough, but even more strangely, my father had unwittingly gestured in the same direction long, long ago.

There was a time in my father’s life in the mid-1970s when he was in trouble and he needed definition: a clear-cut answer. It was a matter of contract. My father had been unlawfully fired.

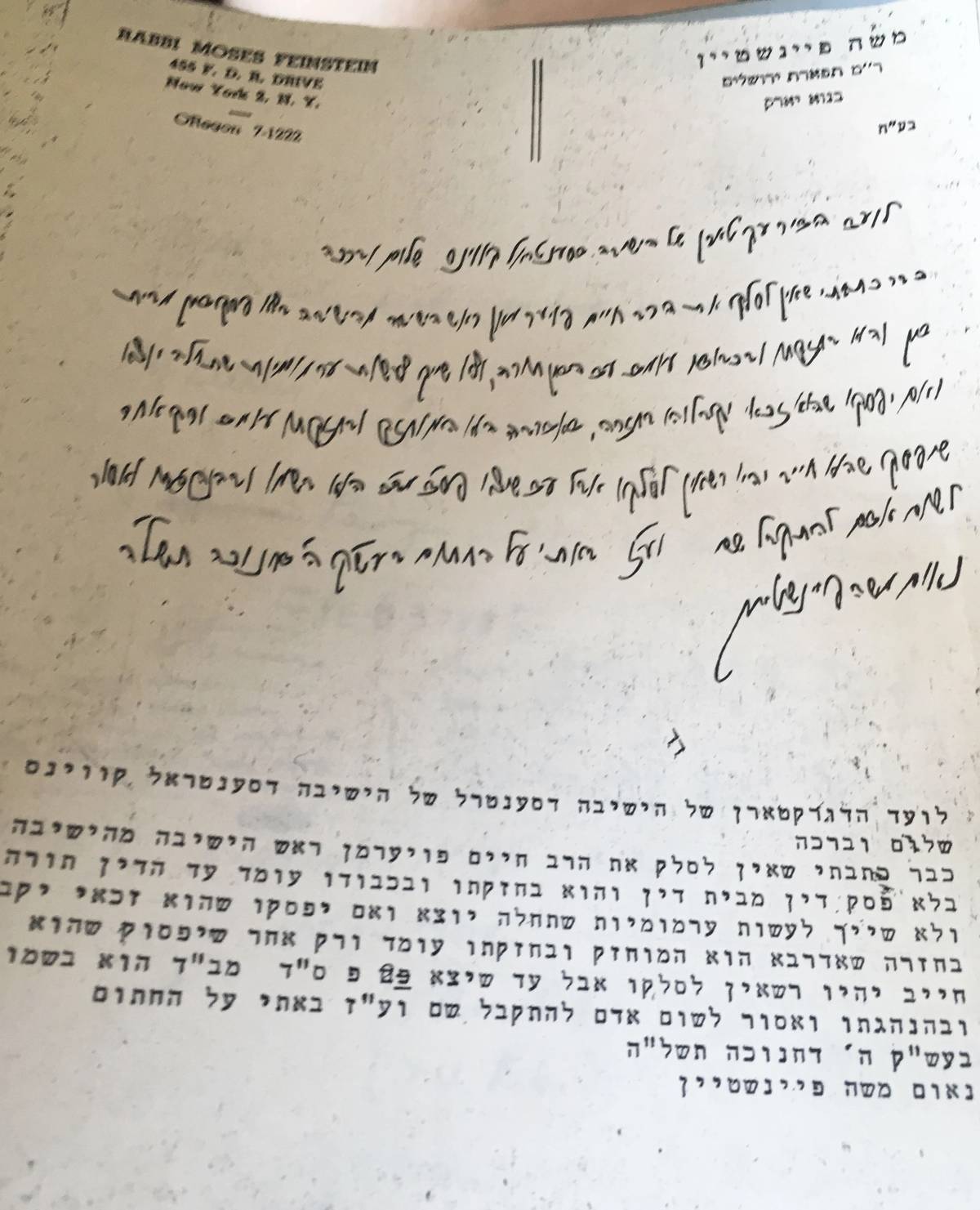

He needed a ruling and an unambiguous one. He went to seek the rabbinic sage of the generation, a diminutive man, who lived on the Lower East Side, a Russian man whose name was Reb Moshe Feinstein.

Dad had waited for 2 p.m., just after the afternoon service, to make a “jump” for the rabbi. The elder rabbi was a modest man, but a world-famous figure and this was the only time a stranger might reach him for serious conversation.

The meeting lasted a few minutes but it was, for my father, the most mystical event of his life. The Russian rabbi, whom he had never before met, spoke to my father in the soothing jargon, the Yiddish of old, and like father to son, comforted my father and wrote a ruling in longhand in the sacred tongue on a piece of his letterhead. My father upon returning home sat at the kitchen table, waved the piece of paper (which he preserved forever in his files) and wept and wept. I was 11 years old and it was the first time I ever saw my father cry. My mother kept trying to ply him with a bowl of bananas and cream and he waved her off, as if to say, “This is the high point of my life and you bring me bananas?”

Reb Moshe was now long gone, but his son Reb Dovid, 90, was still on this earth and occupied the very same position. This is the man to whom so many people had referred me to for advice regarding the money. I tried to reach him by phone but to no avail.

Taking the same steps as my father, I drove to the Lower East Side to the congregation on East Broadway. The windows were caked with grime, as though it hadn’t been washed in 150 years. The paint was stippled, the benches wooden—it had a vaguely Russian feel, like a prewar shtetl in Minsk or Belarus. He, too, had been born in Russia, but came here as a boy of 7.

Like my father before me with the elder Rav Feinstein, I approached the younger Reb Feinstein, a spry and handsome 90, just following afternoon prayer—he, like his father, had the simple manner of a shoemaker, but had the entire Torah on his lips.

“I come here on behalf of my father, recently gone,” I said. “What to do with the money?”

“No heirs?”

“I could advertise to seek them out.”

He shook his head. “No need.”

“My father had preferences for the money …”

Reb Dovid stopped me. “Your father is in heaven now. His preferences are no longer relevant. It’s your day—what do you want to do with it?

I told him my preference: “These people were from the Old Country. Could I give it to a Jewish museum?”

“No, you may not. Only Torah, only Torah. Any place you choose that teaches Torah, you can give it to,” he said. Then he added: “My advice? Get rid of it quickly.”

I took him at his word and drained the account of the money within six hours. I gave the bulk of the money to my father’s (and my) alma mater, Yeshiva Rabbi Chaim Berlin. This was an easy decision since the Kolomear organization would be kept intact, the graves are held in trust, and a proper memory would now be set up for Kolomea. Why Chaim Berlin? My father himself had named it as one of his preferences because for him Torah was always at the center of the Jewish experience. This was the place he had received the Torah that he then gave to me. Besides that, they have a large library, and in it are volumes written by various “sons” of Kolomea or its environs. For example, the Baal Shem Tov is said to have revealed himself in Kolomea and before the war, there was an apartment and mikvah he used there that was later named for him. The Taz and the Pnei Yehoshua, Rav Hillel Lichtenstein, a student of the Chasam Sofer, all giants of Talumdic law, are said to have come from Kolomea or nearby. In fact, Rabbi Josef Lau (later murdered in Treblinka), the great uncle of the present-day chief rabbi of Israel, was the last rabbi in Kolomea. It was not a one-horse town. The sculptor Chaim Gross came from Kolomea, as well as the great 20th-century cellist Emanuel Feuermann, who was my grandfather’s first cousin.

The last chapter of Kolomea is beyond cruel: In 1942 most of the residents were slaughtered in an open field—it is said that 72,000 remaining Jews from Kolomea and the surrounding area lay in a mass grave that was still open for years after the war.

The rabbis taught that when the dead are quoted, their lips move in the grave, a form of resurrection in a minor key, as though God brings them back to life for just a bit. This may be the origin of the well-known expression “Rashi says” instead of Rashi said. He is alive as we quote him.

The venerable Reb Dovid Feinstein has since passed away, but he is alive to me. The rabbi inadvertently showed me that the preferences of the dead are not always binding on the living; my father had given me not just life, but my life. I was to keep my own counsel. That day Rav Dovid, famous for brevity, had in 130 seconds administered a karate chop that sliced through generations of primitive guilt. Your father’s preferences are no longer relevant in this matter. He had his life, now you have yours. With his words, he helped me put Dad at rest with respect to his mother’s wishes. We had both received liberation from an unlikely source.

By the way, it was incredibly loving of my father to buy me a plot near him and my dear mother in the Queens cemetery. However, I have made other arrangements.

Alter Yisrael Shimon Feuerman, a psychotherapist in New Jersey, is director of The New Center for Advanced Psychotherapy Studies. He is also author of the Yiddish novel Yankel and Leah.