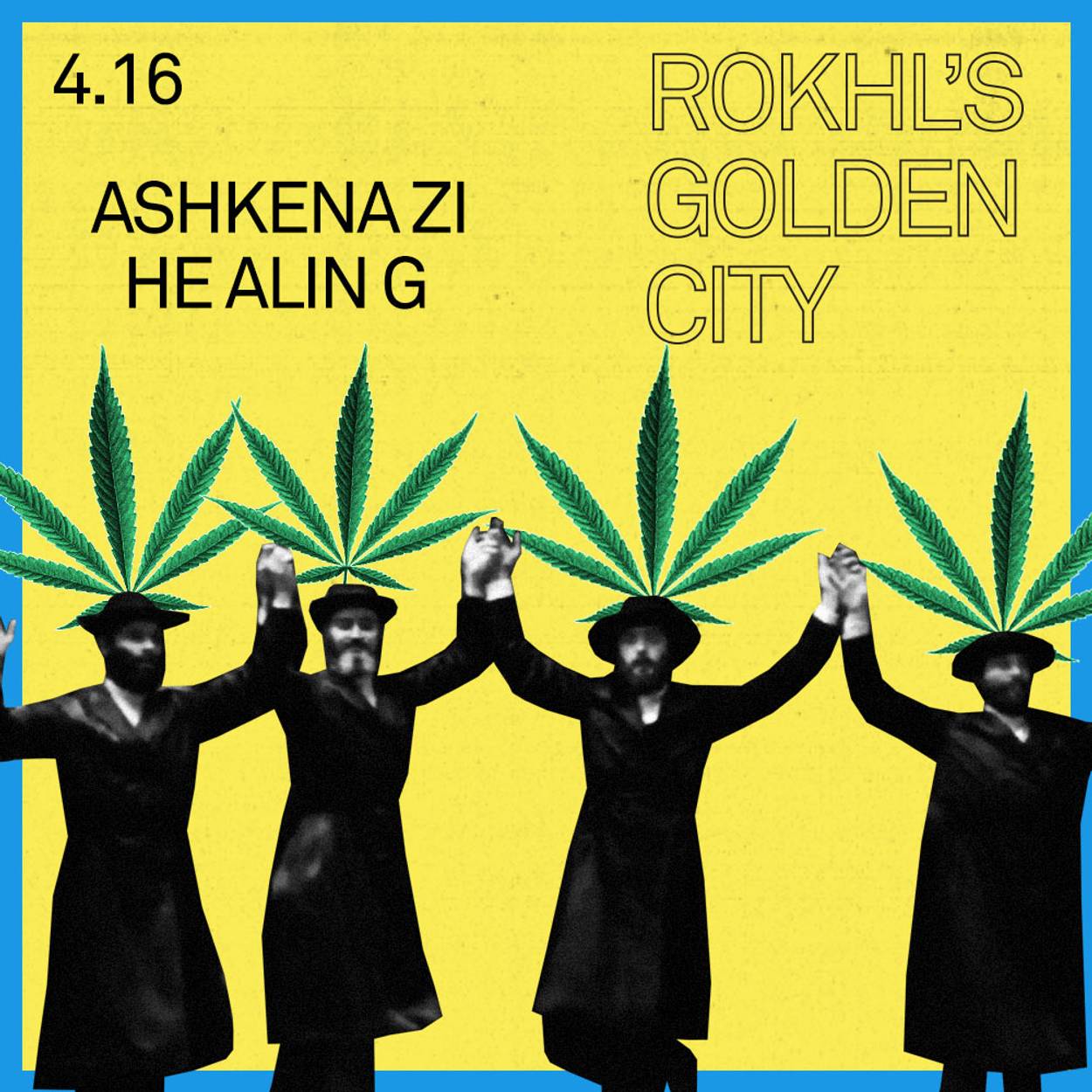

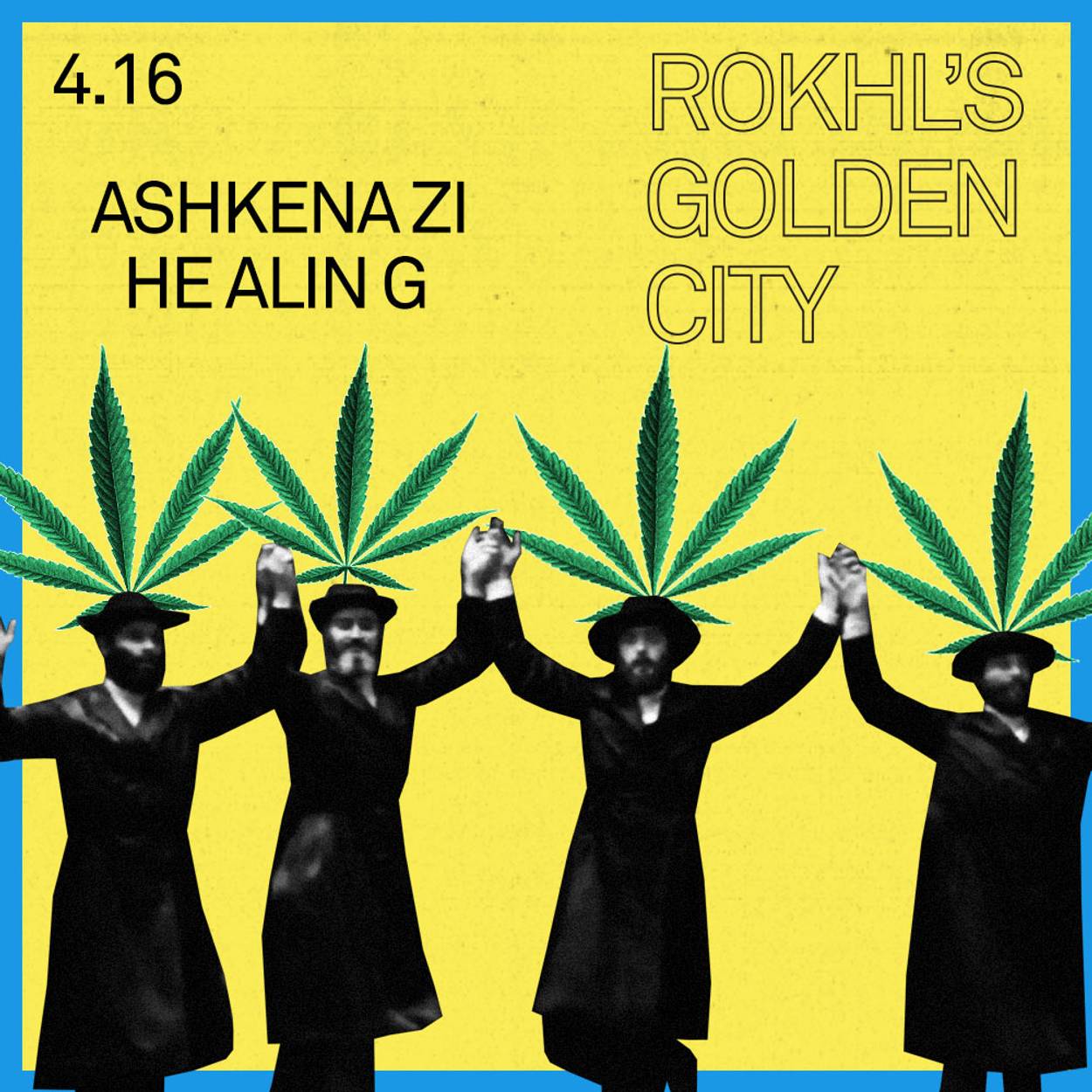

Green Wisdom

Rokhl’s Golden City: The roots of Jewish herbalism

It’s easy to lose track amid the nonstop news churn, but there was some truly joyful, non-vaccine-related news here in New York at the beginning of April. Our governor finally signed legislation decriminalizing recreational marijuana use and expunging the criminal records of those charged with marijuana offenses. We’ve known for years that, though people of color are a smaller proportion of marijuana users than white users, they are arrested at far greater rates. In 2020, for example “Black and Latino New Yorkers combined made up 94% of marijuana-related arrests.” April’s news had everything to do with long-term criminal justice organizing coinciding with an embattled governor looking for a win, and nothing to do with the kind of legalization arguments I remember from my own college days, like the hundreds of “miraculous” uses of hemp and our inalienable right to the sacred plant wisdom held within the leaves of Cannabis sativa.

It may have failed as a justification for legalization, but perhaps that means now is the perfect time to revisit the idea of plant wisdom and remaking our ancestral connections to all kinds of plants, including, yes, cannabis. Consider the story of my friend “Ben,” a fellow Yiddishist and a bit of a botany nerd. While chatting with him recently, he pointed out the difficulty of this kind of work, even when one goes all the way to the Old Country, and even when one has the rare luxury of spending time with native Yiddish speakers schooled in the interwar period. “When I was in [Vilnius, Lithuania], I tried to ask the old folks there about plant lore but didn’t really learn anything,” he told me. “I would sometimes point to common plants like dandelions and ask what they called them, but I think usually people could only remember Russian or Polish names.”

On a walking tour of Kaunas (Yiddish: Kovne), he was led by a particularly energetic 80-something Yiddish speaker, and former Jewish partisan, Fania Brantsovskaya. As Ben told me, “I saw some cannabis growing by the side of the road, so I pointed it out to her and she giggled and said, ‘You can make rope out of it, too.’” Quizzed on the Yiddish name, Brantsovskaya of course knew the answer: kanoplye.

I love this little anecdote for so many reasons. For one thing, in his still-essential reference work, Plant Names in Yiddish, Mordkhe Schaechter notes the common wisdom that it was interwar Yiddish language day schools in Eastern Europe that enriched “the Yiddish language with numerous loan words and new coinages for plant names, organs, and functions.” And Brantsovskaya was indeed a graduate of one of the new interwar Yiddish day schools. Of course, she would be the one to come through with the ancestral plant lore we crave. Or, at least, the biology class vocabulary of the average 1930s Yiddish middle schooler.

As Schaechter writes, those new Yiddish schools in “Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and the Soviet Union taught the sciences in Yiddish; hence the need to fill many gaps in botanical terminology.” Not only that, though she has lived in Vilnius for many, many years, Brantsovskaya was born in Kaunas in 1922. To be guided by a native speaker of prewar Yiddish, through the natural landscape of her own birthplace, has to be among the rarest of rare luxuries for my generation of Yiddishists. It’s a kind of deep rootedness, both figurative and literal, that at least to the Long Island natives among us, seems forever elusive.

At the same time, Brantsovskaya became an adult in postwar, Soviet Lithuania. Starting immediately after the revolutionary period, there had been a push in the Soviet Union to decrease dependence on imported plants and herbs for medicines. Task forces were deployed to survey the traditional botany of various communities, with an eye toward becoming pharmaceutically independent. And it wasn’t just pharmaceutical purposes. In Plant Names in Yiddish, Schaechter argues that clarification of Yiddish botanical terms was necessary to access a wide variety of texts, noting that “quite a bit was written in Yiddish, especially in the Soviet Union” about“ industrial plants …” Brantsovskaya’s giggle about kanoplye’s industrial use reminds us that American college kids were hardly the first to discover the “miracle” of hemp.

The search for ancestral plant lore, and the rootedness it can bring, is at the heart of an utterly fascinating new book, Ashkenazi Herbalism. In the preface, one of the book’s co-authors, Deatra Cohen, describes her experience as a beginning student in the field of herbalism. Her program “encouraged students to get to know our own ancestral healing practices.” But when she went looking for resources on Ashkenazi “medicinal plant knowledge” she found almost nothing. Cohen had many years professional experience as a librarian, as did her co-author, her husband, Adam Siegel. What they found was that there was no existing ethnobotanical survey of the Ashkenazim of Eastern Europe. Downhearted at this nondiscovery, Cohen said, “I didn’t want to feel like an herbal interloper, forever having to refer to other peoples’ traditions, never knowing what plant knowledge my own grandparents had relied on.”

Cohen’s sentiment was entirely familiar to me, and to anyone who has found their way (back) to the traditional language, music, art and foodways of Ashkenaz. But the focus on herbalism was a revelation to me. As I eagerly made my way through Ashkenazi Herbalism, I found myself getting goosebumps more than once. Just a few weeks ago, I published a column on traditional Ashkenazi mourning practices. There, I reflected on the ways this pandemic had changed my relationship to Yiddishland. What had once been an endless source of consolation, joy, and deep fascination, had been tempered by the bodily vulnerability of our plague year. “In the past, reading that a handful of graveyard dirt was considered a cure for helish fayer or kadokhes (i.e., terrible fever) would have secretly delighted my inner Goth kid. But now, delving into the complex world of Eastern European folk medicine, as I did for a column this fall, I found it intolerably upsetting.”

And then, just a few weeks later, along came Ashkenazi Herbalism to make me rethink my understanding of Jewish folk healing once again. In its pages I did indeed find some of the remedies which now seemed so disturbing. For example, in the notes of a 17th-century feldsher (a military trained surgeon-barber who performed many kinds of healing duties), we find that to prevent gangrene in a gunshot wound, a plaster of bread mixed with saliva and cobwebs might be applied. One has to wonder how often that actually worked. (Curiously, spiderwebs show up often as a traditional remedy for cuts, scrapes, and wounds of all kinds, even into the 20th century.)

But Cohen and Siegel’s herbalist perspective brings new light to the broader picture of healing in Jewish Eastern Europe. The book consists of a brief overview of the history of Ashkenazi folk healers, followed by the largest part of the text, a materia medica, or listing of some of the plants and herbs known to be used by “folk healers in towns within the Pale of Settlement with a significant Jewish population between the two world wars.” Cohen and Siegel chose 26 plants, and they provide a wealth of information about each, including their names in multiple languages (Yiddish, Hebrew, and co-territorial languages) as well as their medicinal applications.

And though surely many of the traditional healing remedies were ineffective, leafing through the materia medica, one realizes that an enormous amount of time-tested wisdom lies in these plant medicines, many of which will be familiar to readers and are still used today in many herbal and healing traditions.

As I read, it struck me that a book on Ashkenazi herbalism could not capture the zeitgeist more perfectly. Jewish farming, home pickling, fermented everything. Of course herbalism comes next, right? Where are the Brooklyn vendors offering the neo-artisanal Yiddish tinctures, syrups, bitters, and healing teas I need? (I can forage the spiderwebs from my own windowsill, thanks.)

For confirmation of my hunch, I reached out to my friend Jeffrey Yoskowitz, co-author of The Gefilte Manifesto cookbook and my own personal touchstone on all things Jewish and fermented. “Fermentation was what roped me in,” Yoskowitz told me. “I never knew there was deeper wisdom to my cultural traditions, that Jewish pickles weren’t just a free deli side but were magical, nourishing, probiotic foods that played a fundamental nutritional role in the Jewish Eastern European diet. What else didn’t I know? Upon visits to Eastern Europe, I learned … how important foraging for mushrooms was to Ashkenazi history, as well as foraging for berries, herbs, and even horseradish. All that knowledge was lost as my ancestors adapted to American life. I see the interest in Ashkenazi herbalism as an extension of that question: What else didn’t I know?”

As Cohen and Siegel found, answering that question is not an easy task. A fascinating aspect of Ashkenazi Herbalism is how the authors pieced together the materia medica from scattered and diverse sources. One of their most important sources ended up being a Soviet ethnobotanical survey with the unpromising name of Herbs Used in Ukrainian Folk Medicine. Despite the name, the authors’ research convinced them that though Jews are not named therein, the plants and traditions described are almost certainly Jewish. The Jewish towns and villages listed in the survey, along the west bank of the Dnieper, fit the criteria of the scientists looking to study and scale up indigenous plant wisdom. These towns and villages were long settled and had not yet been collectivized. This meant that the people there had hundreds of years of connection with the local ecosystems and locally rooted healing traditions.

The authors of Ashkenazi Herbalism present their work not as a comprehensive end point, but the beginning of a journey. If I have any critiques or quibbles with the project, it’s mostly that the authors rely heavily on English language translations and not enough Yiddish-language primary sources. I’d love to see the book connect with the new generation of Yiddishists who have the advantages of being connected to each other, as well as having an entire universe of primary sources available digitally, meaning that specialized information can now be gleaned, gathered, and organized in ways previously unthinkable.

Moreover, the story of Ashkenazi healing continues the ongoing work of writing the marginal back into Jewish history. In Ashkenazi Herbalism we find so many of the unwritten stories of women: the midwives, evil eye exorcisers, professional mourners, and more. Whether you’re in it for the gender analysis, the Bubbecore aesthetic, or because your inner Goth can’t wait to use a spider web as a bandage, it’s a project that offers important answers, and questions, for a time that needs all the healing it can get.

LEARN MORE: Buy Ashkenazi Herbalism here … KlezCalifornia and Jewish Learning Works will co-present a talk by Deatra Cohen and Adam Siegel on May 6 at 7 p.m. (PST) Register here …

REFERENCE: One of the most comprehensive Yiddish reference works on all things botanical is Di geviksen velt in yidish (Plant Names in Yiddish: A Handbook of Botanical Terminology), by the late Dr. Mordkhe Schaechter. Schaechter began working on the book in the 1960s and finished the bulk of it in the 1970s. The introductory chapters were written in the 1990s but it was only published in 2005, with much assistance coming from the book’s publisher, YIVO. You can download Plant Names in Yiddish as a PDF for free. It’s not exactly user-friendly, but what it lacks in ease of use, it makes up in its richness in not just terminology, but linguistic and folkloric insights. … All the way back in the summer of 2008, I sat next to Marek Tuszewicki in our YIVO summer refresher course. Today, Marek is the deputy director of the Institute of Jewish Studies at Jagiellonian University in Kraków. His latest book on Jewish folk medicine, A Frog Under the Tongue: Jewish Folk Medicine in Eastern Europe, is finally out in an English language edition. Frog Under the Tongue is a complementary volume to Ashkenazi Herbalism, offering an academic look at the larger field of traditional healing in Jewish Eastern Europe.

ALSO: On the afternoon of May 2, Yiddish scholar Dovid Katz will talk about his father, the poet Menke Katz, and the world of the radical Yiddish writers of Proletpen. Register here … On June 10, YIVO will host a fascinating afternoon talk, “Jewish Anarchist Women 1920-1950: The Politics of Sexuality.” More information here … On June 17, Eddy Portnoy will be talking about the Modicut Yiddish Puppet Theater for the Yiddish Book Center… Klezkanada has just announced its 2021 program, Aug. 23-27. Unfortunately, the retreat will once again be a virtual affair, but, circumstances permitting, Aug. 28 and 29 will feature in person concerts in Montreal. More info here … Who knows what international travel is going to look like in the coming months, but if I had the money, I’d immediately book my tickets for this October 2021 event on the Isle of Man. Organized by Jewish Renaissance magazine, it’s a historical tour and blue plaque unveiling ceremony, honoring the 80th anniversary of a shameful episode in British Jewish history: the internment of thousands of Jewish refugees from Nazi Europe.

Rokhl Kafrissen is a New York-based cultural critic and playwright.