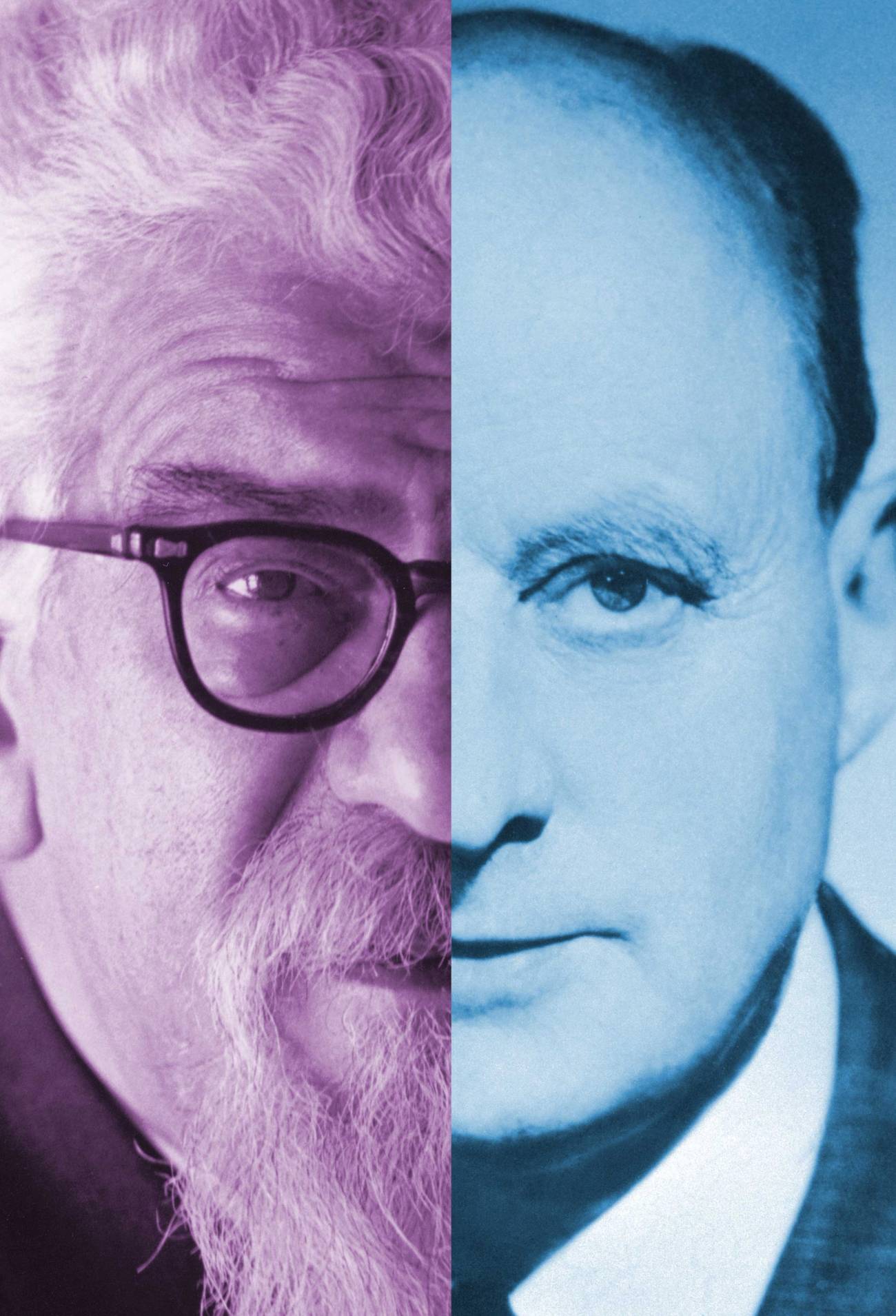

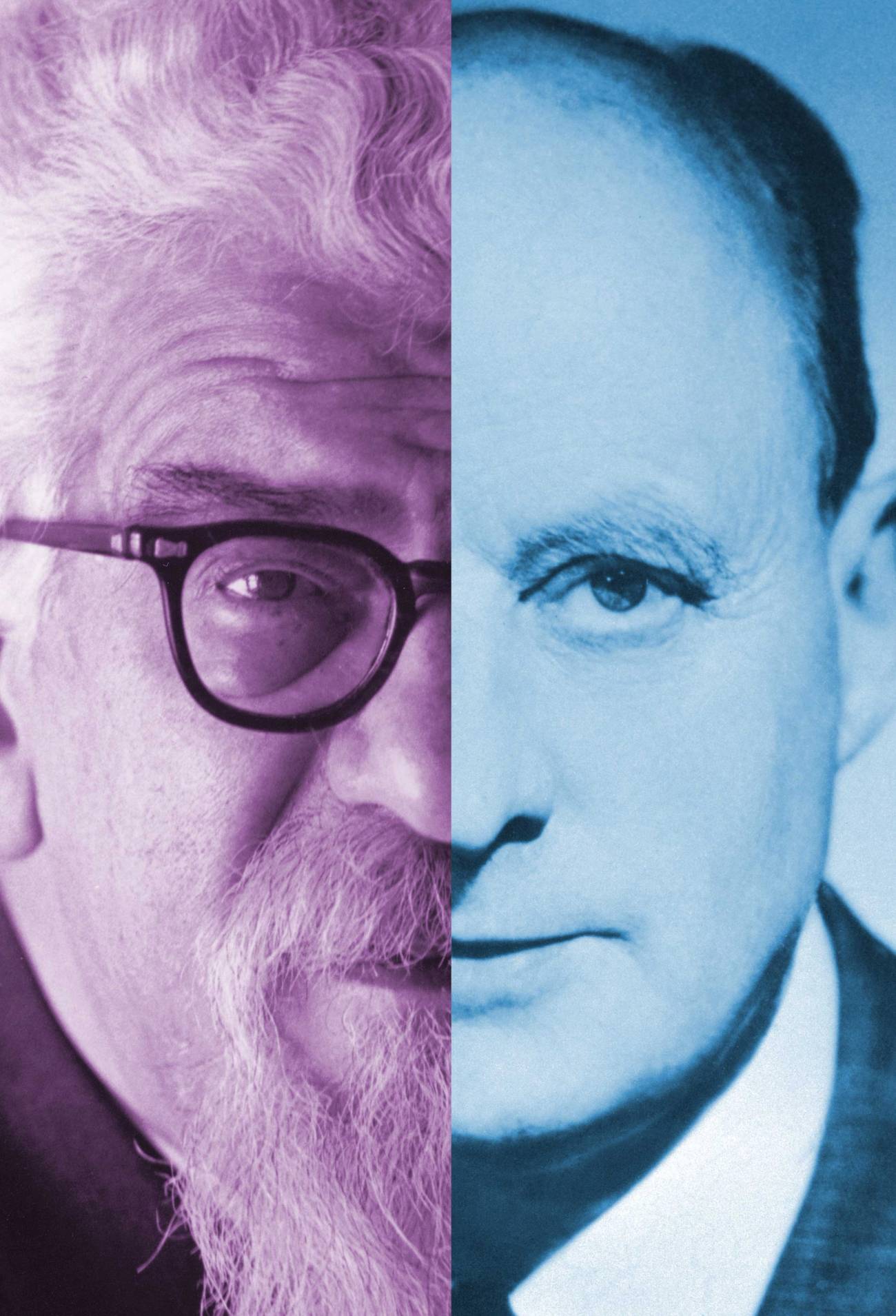

An Unlikely Friendship on Seminary Row

Looking back on the connection between Abraham Joshua Heschel and Reinhold Niebuhr, 50 years after their deaths

Half a century has now passed since the deaths of two of America’s most influential 20th-century religious figures: Reinhold Niebuhr (1892-1971) and Abraham Joshua Heschel (1907-72). For decades, Niebuhr taught at Union Theological Seminary (UTS), which has trained mostly mainline Protestant clergy for nearly two centuries. Heschel taught just across the street at the Jewish Theological Seminary (JTS), founded in 1886 as a nerve center of the Conservative movement, once the largest in American Judaism, sitting midway between the traditionalist Orthodox and the liberal Reform. Both storied New York City institutions near Columbia University still stand out like twin cherubim on opposite sides of Broadway’s sloping arc. They call the area Seminary Row.

Heschel and Niebuhr still matter. Their insights about human nature are still cogent. And their lives remain beacons of integrity and purpose, in counterpoint to decades of disillusioning clerical scandals that followed. But their name recognition has diminished in a more secular America, where the percentage of religiously unaffiliated, millennial “Nones” (many now with young families) has climbed to a new high of about 1 in 3.

It’s hard to conjure American religious leaders today with an impact as sweeping as Niebuhr and Heschel. They reached across divides—religious and secular, liberal and conservative—engaging even those with whom they strongly disagreed. They can bring a nuanced perspective to this period of partisan rancor, when too many of us are siloed off from others in particularized and polarized bubbles.

To mark the 50th anniversaries of both men’s deaths, Yale and Oxford University presses have issued a new biography of Heschel and the most exhaustive handbook ever published on Niebuhr. Both have also been the subject of public television documentaries by the Emmy Award-winning filmmaker Martin Doblmeier.

Although their adjoining seminaries embodied rival religions historically enmeshed in theological hostility for nearly two millennia, Heschel and Niebuhr gradually and poignantly became friends. In addition, Niebuhr became the first Seminary Row professor ever to formally address the joint faculties of UTS and JTS. And, according to UTS’s Mary Boys, a leading scholar on Jewish-Christian relations, Heschel became the first Jew to be appointed a visiting professor at UTS.

When Heschel died, a close JTS colleague delivered the eulogy at his funeral. But shortly before Niebuhr died, he chose Heschel from the other side of Broadway to be his eulogist, although Heschel’s heritage was very different from Niebuhr’s. It was the capstone in a relationship of common ground amid striking contrasts.

To remember their legacies and their seminaries jointly 50 years later seems fitting, especially when measured against the equally contrasting backdrop of their more conformist, though also more consensus-seeking, midcentury American religious landscape.

Niebuhr hailed from rural Missouri, and was ordained by the German Evangelical Synod, an amalgam of Lutheran and Calvinist traditions now part of the United Church of Christ. Heschel was a Warsaw-born child prodigy from celebrated Hasidic dynasties. Unlike his mother and three sisters, all later murdered, Heschel fled Poland six weeks before the Germans invaded.

The two were different in other ways. Heschel called himself “an optimist against my better judgment.” As a poet who taught classes on mysticism, he was a florid and lyrical writer who sensed God’s presence through “radical amazement”—a feeling of awe for everyday wonders. In Heschel’s conception, God is “near to us,” affected by human joy and suffering, and desirous of a creative partnership with humans that is advanced by righteous living. It is a theology that has resonated with both Jews and non-Jews. Heschel is surely the only American Jewish theologian whose writings have been translated into Korean, Portuguese, and Urdu.

Niebuhr is best known for his Serenity Prayer, spotlighted by Alcoholics Anonymous in battling addiction. Niebuhr was somewhat pessimistic and hardly mystical. He was called a “crisis” theologian, reeling from the then-unprecedented carnage of WWI and its shattered optimism. Ultimately, this reaction may have tilted too far toward disillusionment with human nature which, according to William Hutchison, the historian of American Protestantism, “predominated in nearly everything Reinhold Niebuhr was writing” in his heyday. Niebuhr became a tough-minded, hard-hitting anti-utopian with a brisk, unadorned style, chiefly associated with the concept of Christian Realism.

Niebuhr broke ranks with other clergy in the 1930s over pacifism, which he came to see as naïve. Although he remained an activist his entire life, he also took aim when starting out at the optimistic presumptions of the Social Gospel Movement in liberal Protestantism. Niebuhr concluded that “historic religion has a note of provisional pessimism in its optimism, for the simple reason that it takes cognizance of more of the facts of human existence.” Recurring human failings, therefore, could only be managed, not eradicated. We must still try to do what we can, though we are bound to fall short in our pursuit of justice and love. We must, as the Serenity Prayer goes, have the courage “to change the things that should be changed.” Beyond this, Niebuhr asks God to “give us grace to accept with serenity the things we cannot change,” and also “wisdom to know the difference.”

Heschel’s closeness to Niebuhr is puzzling for another reason: As a fully observant Jew, he seems more traditionally religious than Niebuhr was. Heschel’s daughter Susannah, a Dartmouth professor, notes that Niebuhr was drawn to the practical message of the Hebrew prophets—their rebukes of corruption and hubris. Heschel, however, also stressed divine revelation from a living God because, as Fritz Rothschild, the first to systematize Heschel’s thought, points out, in Heschel’s Hasidic childhood, “the presence of God was a daily experience.”

Niebuhr, on the other hand, called himself a quasi-secular Protestant and deemphasized biblical revelation. UTS’s Gary Dorrien calls his predecessor’s religious ideas “very liberal,” extending to a view of “biblical narratives and the doctrines of Christ and the Trinity as mythical.” While some Jewish scholars took issue with concepts in Heschel’s theology, they never argued he was insufficiently Jewish. But Niebuhr seemingly is seen in some quarters as not Christian enough.

There were, however, personal similarities between the two that may shed light on their unlikely friendship. As young men, for example, both strived to move beyond their provincial backgrounds. Niebuhr never had a Jewish friend until he was in his 30s, and Heschel never knew anyone who was Black until he arrived in America. And yet Niebuhr, like Heschel, was no stranger to the pain of bigotry. His father was a recent immigrant, and Niebuhr grew up speaking German. For over a decade, he pastored a German American congregation in Detroit. The WWI anti-German sentiment caused his denomination to delete the word “German” from its name, and also caused his more retiring theologian brother to switch from Helmut Niebuhr to H. Richard. (Reinhold, however, remained “Reinie” to friends and even students.)

Both theologians were the sons of clerics. They quickly chose their fathers’ profession and never looked back. Then they settled in at their respective seminaries and never left. Both married later in life (Niebuhr married a much younger UTS student), and both had daughters in their 40s. (Niebuhr also had a son.) Both daughters, in their own writing, have delved into issues that disturbed their fathers, such as the generally dispiriting performance of Holocaust-era German churches.

Both Niebuhr and Heschel were aphoristic essayists, and better preachers and public intellectuals than cloistered academics or systematic theologians.

Both were initially outsiders. Niebuhr never had the luxury of studying for a doctorate. He also called himself a country bumpkin because he lacked the punctilious social graces of the more high-born, starched-collar WASP faculty members of the era. So, too, Heschel’s common-person, heart-over-head Hasidism came with emotion more befitting a Pentecostal than a Presbyterian, despite Heschel’s vast erudition. This was not a good fit for the detached, sometimes elitist text scholars who made JTS, according to its new chancellor Shuly Rubin Schwartz, the epicenter of Wissenschaft scholarship, a German rationalist “science of Judaism.”

Both Niebuhr and Heschel were aphoristic essayists, and better preachers and public intellectuals than cloistered academics or systematic theologians. Niebuhr in particular was a riveting orator, who used both voice and gesture to hammer home his points like a seasoned trial lawyer.

Finally, Heschel and Niebuhr were ferociously hard workers who generated a torrent of writing, even as they also taught, traveled, and engaged in politics. Exhausted by too many commitments, Niebuhr wasn’t even 60 when he had a stroke that rendered him a semi-invalid. This exacerbated his struggles with family depression. But he lived on in a diminished state until 78, while Heschel, who had a first heart attack at 62, died suddenly in his sleep at 65 after a Sabbath dinner with friends. Today Heschel’s small book The Sabbath, on the idea of a day of rest, remains his most popular work, and a gateway to his spiritual orientation. Coincidentally, it will also be the topic of Doblmeier’s next documentary.

Niebuhr’s thinking was never static. He outgrew both pacifism and socialism. Eventually, he became a Cold War anti-communist championed even by neoconservatives. But early on he learned from the leading lights of then-contemporary liberal Protestant theology, a remarkable number of whom were German-speakers, and some of whom harbored condescending views of Judaism as passé. Their term Spätejudentum (“late” Judaism even in the first century CE) suggested a jalopy on its last legs, ready for the junkyard. Heschel, whose doctoral dissertation in German focused on the consciousness of the Hebrew prophets, wrote and taught in that language as well as Niebuhr did, including briefly as a successor to Martin Buber at a school in Frankfurt. Buber is the only other 20th-century Jewish theologian besides Heschel with a comparably large influence on Christians.

More Americans have German ancestry than English or Irish, but Niebuhr, like many other 20th-century German Americans, was an assimilationist. He never changed his name, but he exhorted his immigrant congregation to become fully American and relax their attachment to a Germanic past. Nevertheless, he despaired over the rise of the Nazis in the homeland of his parents, seeing in Nazism the reversion to a primitive tribalism that displaced God to worship an idealized Volk. Niebuhr’s daughter Elisabeth Sifton, a prominent book editor, divorced her first husband and married the refugee Columbia historian of Germany, Fritz Stern, who was consumed by a “burning question that I have spent my professional career trying to answer: Why and how did the universal potential for evil become an actuality in Germany?”

After the war, Niebuhr visited the family of his most famous student, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, about whom Doblmeier has also made a documentary. Bonhoeffer studied at UTS on a fellowship, long before he was hanged in 1945 for his complicity in a nearly successful plot to kill Adolf Hitler. Niebuhr saw in this Lutheran theologian’s martyrdom “the hope of a revitalized Protestant faith in Germany.” Heschel, by contrast, would never return to Germany or Eastern Europe, haunted by images “of mothers burned alive, of human beings asphyxiated.” He found it difficult to write much explicitly about the Holocaust, though he blamed humans, not God, for the catastrophe.

Heschel and Niebuhr were both protagonists in dramatic, seminary-based rescues from Nazi tyranny. Heschel’s ticket to New York was procured through the Reform movement’s Hebrew Union College, which offered him a position in Cincinnati, where he remained for five years. Niebuhr helped rescue the anti-Nazi theologian Paul Tillich, yet another son of a Lutheran clergyman, saved from the clutches of the Gestapo in Frankfurt. Niebuhr telephoned Tillich on one of his trips to Germany, inviting him to join the UTS faculty. Its members voted to contribute 5% of their Great Depression salaries to fund the position. Niebuhr and Tillich would go on to become the Mantle and Maris of UTS in the immediate postwar years, theological power hitters whose impact exceeded all the others.

Heschel and Niebuhr cannot be fully understood outside the context of the illustrious seminaries in which they were planted. As Serene Jones, UTS’s president since 2008, notes in her recent autobiography, “seminary” comes from the word for seed plot. Seminaries teach clerics-in-training to harness religion to help others mark, interpret, and share the joys and burdens of life. For Niebuhr and Heschel, this became their life’s work, and their seminaries remained their home base, though each was distinctive. UTS was generally more liberal than JTS, which Gordon Tucker, the former JTS rabbinical school dean, characterized as “intellectually open-minded but more traditional overall.”

“Theology” is a word that can emit a musty, medieval odor. But Heschel relished his role as a JTS theologian. He complained in a 1966 Newsweek profile that “[t]he content of American Judaism is profoundly anti-theological. We have forgotten that Judaism is a way of thinking as well as doing.” But he was not entirely right. According to Jonathan Sarna, the historian of American Judaism, in the postwar suburban synagogue boom and religious “revival” that may have been as much a search for stability and belonging, there was an “unprecedented interest in Jewish theology and religious thought.”

Niebuhr, on the other hand, preferred to see himself as a social critic more than a theologian. And Niebuhr’s focus on international affairs influenced government officials as much as clerics and seminarians. Presidents Obama and Carter, and many foreign policy experts, have credited his influence on them.

Some shy away from Niebuhr’s thought because they think it is too entangled with Christian views of original sin. Heschel obliquely suggested as much in a respectful and admiring mid-1950s evaluation of Niebuhr’s thought. But Heschel in his later writings admits his own thinking is also divided between the sin-focused, dyspeptic Kotsker Rebbe, whom Heschel compared to the Protestant progenitor of existentialism, Soren Kierkegaard, and the joyous, accepting attitude of the founder of Hasidism, the Baal Shem Tov. Niebuhr himself protested that his notion of sin as human weakness is not that far removed from the Jewish “doctrine of yetzer hara (evil inclination).” And, according to Niebuhr’s UTS colleague Roger Shinn, who also crossed Broadway to teach at JTS, irony in Niebuhr’s thought eventually “comes to occupy the place that sin [had] occupied.”

Irony in Niebuhr’s theological arsenal demonstrates that we are not as savvy and virtuous as we think. In The Irony of American History, he found the concept rooted in human limitations like sin but more light-hearted because it points to “cosmic absurdities that provoke reflection and humility.” It lives with tensions even if they are not easily reconciled. It points us to unintended consequences. The solution to one problem often creates other problems, such that democracy itself is forced to come up with ‘‘proximate solutions for insoluble problems.” Irony sees truth emerge in paradox, as in Niebuhr’s second-most-quoted adage: “Man’s capacity for justice makes democracy possible; but man’s inclination to injustice makes democracy necessary.” Heschel himself was an illustration of irony and paradox, a rationalist Talmudic scholar who loved mysticism, a traditionalist believer who was also a religious pluralist—calling the denigration of any of the great religious traditions the “height of arrogance.”

Some will gravitate to the cooler, more earthbound Niebuhr while others will prefer the fervent, more spiritual Heschel.

One of the most interesting ironies is that Heschel said he sometimes thought Christians understood his theology better than Jews did. The foremost Roman Catholic Heschelian, John Merkle, thought Heschel “may have done more to inspire an enhanced appreciation of Judaism among Christians” than anyone in the post-biblical era. Meanwhile, Niebuhr, this son of the German Evangelical Synod and the dominant American Protestant public theologian of the 20th century, had extensive Jewish sympathies. Heschel himself found Niebuhr’s thought largely congruent with key aspects of biblical thinking in Judaism. And the Niebuhr biographer Richard Wightman Fox wonders what was specifically Christian, as opposed to Jewish, about Niebuhr’s steady focus on the Hebrew prophets?

Will Herberg wondered, too. Herberg, author of a 1955 bestseller on the American religious scene, had no Jewish education, and sought spiritual counsel from Niebuhr. Niebuhr urged him across Broadway to JTS, and Herberg eventually became a noted theologian himself and the prime Jewish Niebuhrian.

Niebuhr not only refused financial help to relatives who supported the Nazis, he was also among a small minority of Protestant intellectuals who wrote in worry over the fate of European Jewry post-Holocaust. He also understood some common elements of conspiracy-obsessed, nonreligious antisemitism that apparently have not changed much since the Nazis. As Deborah Lipstadt, the Biden administration special envoy on the subject, put it recently: “The Jew is seen as more powerful, the Jew is richer and is smarter, but in a malicious way.” As such, Niebuhr repeatedly advocated for the creation of Israel as a haven against enemies.

The biographies of Heschel and Niebuhr are rewarding in themselves, but especially because both spoke out against clear injustice. To Heschel, faced with a dead end as he tried vainly to save his European family, indifference was among the greatest sins. Except for his role as a Jewish emissary with definite views on proposed Catholic reforms that constituted the Second Vatican Council, Heschel is better known today for his civil rights work than for his theology. A Selma-to-Montgomery march captured Heschel in an iconic photo looking like a prophet with his flowing white hair and beard, marching in the front row with his friend Martin Luther King Jr., at real risk of being beaten. It also recalled when King cited Niebuhr in his well-known “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.”

This is yet another reason why, though they lived in another time, remembering and reading both Niebuhr and Heschel are still worthwhile. Some will gravitate to the cooler, more earthbound Niebuhr while others will prefer the fervent, more spiritual Heschel. Heschel radiates an authentic gratitude for being alive; Niebuhr instills a sensible caution about trying to remake our flawed humanity. But if they were alive today, they would not be trying to win over what the 19th century’s most influential Protestant theologian, Friedrich Schleiermacher, called the “cultured despisers” of religion as much as the 21st-century shoulder-shruggers, the Nones who are increasingly indifferent to denomination-centered religion, which no longer seems germane to their lives.

Five decades after their deaths, we can say that Heschel and Niebuhr, these unlikely friends, were understandably drawn to each other. The differences in their backgrounds amid their shared religious enterprise must have created a mutual fascination, but those differences were offset by even greater similarities. Nevertheless, Fox, who wrote the best-known Niebuhr biography, does not mention Heschel at all except for his eulogy. And Edward Kaplan, author of a two-volume Heschel biography, confirms that the relationship has been largely undocumented.

Ursula Niebuhr published a reminiscence of her husband’s friendship with Heschel. Their interaction seems to have been mostly confined to walking and talking on Riverside Drive near the seminaries where they both lived. Niebuhr’s doctors insisted that he must walk regularly because of his strokes and his depression. For years Heschel kept him company.

Niebuhr’s daughter Elisabeth Sifton discusses the friendship and the walks warmly in her own memoir, though she can’t be sure what exactly they talked about. Although there apparently are more religiously Christian Heschelians than religiously Jewish Niebuhrians, Niebuhr did have a number of prominent secular Jewish friends, including Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, the Oxford philosopher Isaiah Berlin, and the Columbia literary critic Lionel Trilling. But somehow, according to his daughter, “despite a lifetime’s devotion to the Hebrew Bible and a lifetime habit of philo-Semitism,” Niebuhr “had few associations, let alone friends, among America’s rabbis.”

Susannah Heschel is the only one of these three relatives who mentions the eulogy in her writings. The eulogy was delivered at the First Congregational Church in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, home for a time to the Puritan Jonathan Edwards. In 1741 at a different church, Edwards preached one of the best-known sermons in American history titled “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.” The sermon provided a graphic warning of the terrors of hell that awaited those who strayed from the true Calvinist faith.

Edwards believed that God would ultimately return the Jews to their ancient homeland, but he still likely would have been surprised to see his fellow theologian, the distinctly non-Calvinist Rabbi Heschel, addressing the Stockbridge congregation. Indeed, the scene of the eulogy must have been spellbinding in its quiet drama, especially given not only Heschel’s unapologetic Judaism but also Niebuhr’s exalted status in the larger Protestant world.

Heschel’s theology makes compassionate deeds the centerpiece of humans partnering with God in trying to create a better world. Humans are a symbol of God, and the human “deed is the source of holiness,” he wrote. Niebuhr himself had written that while we “may be quite unable to define the meaning of life,” we may still “live by a trust that it has meaning,” that how we conduct ourselves is important. So, it was entirely characteristic of Heschel to praise his departed friend and mentor by saying that “Niebuhr’s life was a song in the form of deeds.” The same also could be said of Heschel’s life. And maybe their friendship alone is enough to explain why Niebuhr chose Heschel for the eulogy, who would be dead himself barely a year later. Or maybe Heschel and Niebuhr were both making one final Seminary Row pilgrimage across Broadway.

For more than two decades Gordon Mehler, a lawyer, has lived near the neighboring seminaries where Heschel and Niebuhr taught. His articles have appeared in The Atlantic, The New York Times, and The Wall Street Journal.