Illustrious

Simms Taback, prolific children’s book author and illustrator and designer of the original McDonald’s Happy Meal, creates art that is kooky, zany, poignant, and seriously Jewish

Simms Taback is my favorite children’s book artist. This is like saying that John is your favorite Beatle, or Pee-wee Herman is your favorite tiny-suit-wearing bow-tied rouged freak: It’s not exactly going out on a limb. Everyone who knows anything about children’s books knows that Simms Taback is a genius.

Taback, who is an author as well as an illustrator, has written more than 40 children’s books, won a Caldecott Medal (the highest honor in children’s book illustration), made The New York Times Best Illustrated Children’s Book list twice, received several Notable Book designations from the American Library Association, and won a handful of Sidney Taylor Awards. But even more important, his work is the rare beast that appeals to actual children as much as it does critics. It’s colorful and antic and silly, and it’s studded with little visual treats and hidden surprises. It blends collage, typography, boldness, and delicious teeny details. His fondness for cumulative rhymes (in books like This is the House that Jack Built and There Was An Old Lady Who Swallowed a Fly) makes for books beginning readers can read to themselves and giggle at over and over.

So who is this wonder? Born in 1932, Taback grew up in the Coops, the cooperative housing project in the Bronx that housed many immigrant Jewish garment workers. His father was a housepainter and labor organizer; his mother was a seamstress and proud member of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union. Taback was named after Harry Simms, a Jewish labor leader murdered in 1932 while helping the mineworkers in Harlan County, Kentucky, unionize. (The other Simms was memorialized in a ballad popularized by fellow labor sympathizer Pete Seeger.)

Taback attended Camp Kinderland and other socialist Jewish camps, where his artistic talents were applauded and where he was encouraged to apply to the New York City’s High School of Music & Art (now known as LaGuardia). From there he went to Cooper Union, served in the Army during the Korean War, and began working as an art director shortly thereafter. In 1974, doing his power-to-the-workers parents proud, Taback began organizing freelance illustrators, helping to form the Illustrators Guild (which later merged with the Graphic Artists Guild) and serving as its first president.

While designers may appreciate Taback for his contributions to artists’ rights, parents appreciate him for making kids love books. His works are sneaky, because they are simultaneously fun and smart, two great things that don’t always go well together.

“Simms’s work is deceptively childlike,” says Taback’s onetime editor Regina Hayes, now the publisher of Viking Children’s Books. “When you begin to really look you appreciate the sophistication of the design, the color sense, the spatial relations—it’s all incredibly clever.”

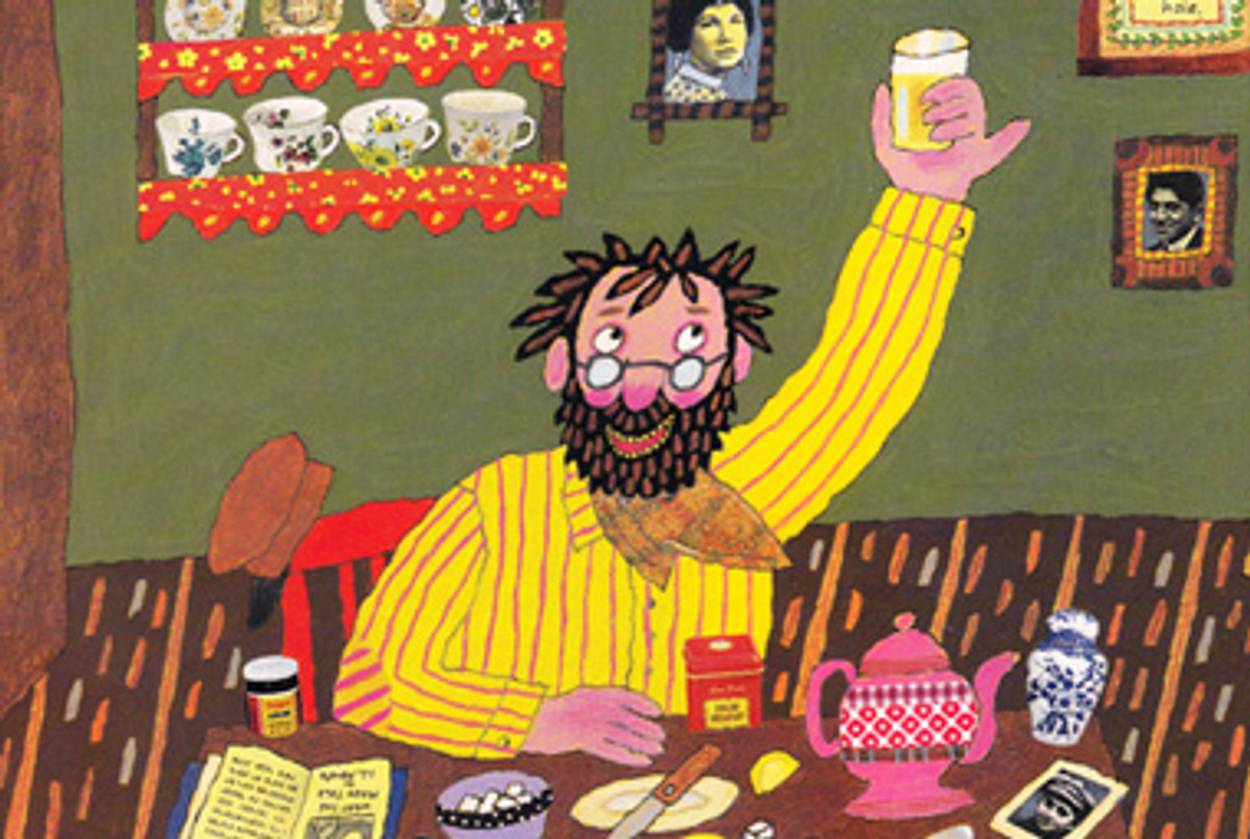

And, boy, do his books feel Jewish. His 1999 Caldecott-winning Joseph Had A Little Overcoatis adapted from a Yiddish folk song and set in an idealized shtetl. Joseph’s overcoat gets increasingly worn, so Joseph turns it into a jacket, a vest, a scarf and so on, until it becomes nothing. And then he writes a book about it. The moral: You can always make something out of nothing. (A good lesson for tailors, storytellers, and bored children on rainy Sundays.) Kids can peek through cutouts in the pages at the ever-changing, ever-shrinking coat. Hidden in the illustrations are a collaged Tevye poster, photos of different fabrics, a teeny copy of the Yiddish Forward—so much texture you could plotz.

The book feels airy and effortless, but it clearly isn’t. “Yiddish was my first language,” Taback said at the Caldecott dinner in 2000. “When I started school, I forgot all the Yiddish I knew as a child. So when I started to do the artwork for Joseph, I knew I had research to do. I started at the Workmen’s Circle bookstore on East 33rd Street in Manhattan. I found five or six books on Jewish life in Poland and Russia with many wonderful photos and a video of the Jewish section of Vilna in Poland before World War II. I visited the Jewish Museum to see articles of clothing and other artifacts. … I illustrated the ethnic clothing by using collage fragments from various catalogues. So even as I created the artwork for Joseph, I was making something new from something discarded.”

Kibitzers and Fools: Tales My Zayda Told Me is another explicitly Jewish book. It features old Eastern European jokes, folktales, and Chelm stories interspersed with Taback’s trademark googly-eyed citizenry, jam-packed layouts and excellent chickens. (No one draws a chicken like Taback.) It’s dedicated to Sholom Aleichem, I.L. Peretz, and Mendele Mocher S’forim. Though most of Taback’s books are like Levy’s Jewish Rye—you don’t have to be Jewish to love them, but it wouldn’t hurt—this one might not resonate with your average Episcopalian second-grader. The specific rhythms and shruggy, rueful, “nu” tone are a definite “hamavin yavin” situation.

But even the non-Jewish books give off Jewish vibes. A note at the end of This Is The House That Jack Built suggests that the famous rhyme was probably derived from “an ancient Hebrew chant”—Taback is referring to Chad Gadya. And in his voice, the nursery rhyme does indeed feel like a Passover melody. In I Miss You Every Day, based on Woody Guthrie’s “Mail Myself to You” (Guthrie’s estate wouldn’t give Taback permission to futz with the lyrics, so he wrote his own), Taback finds the sweetly minor-key, melancholy tone of a klezmer violin. A little girl misses an unnamed someone and mails herself across the country to this person. Could that mix of joy and mystery and sorrow feel any more Jewish?

Many of Taback’s works feature flaps and die-cut holes, but his forthcoming book, Postcards from Camp, due in June, takes interactivity to a whole new level. An epistolary novel about a homesick boy at sleepaway camp and his supportive dad, the story is told in postcards, foldouts and inserts. “It’s Griffin and Sabine meets ‘Hello Muddah, Hello Faddah’,” says Taback’s current editor, Nancy Paulsen, president and publisher of G.P. Putnam’s Sons. (See the slideshow for an exclusive peek at the forthcoming book.) The book brought tears to my eyes: My dad wrote wonderful letters when I was an emo little drama queen at Camp Yavneh and Camp Ramah, and I miss him every day.

“When a simple story touches emotional strings, that’s where the best children’s picture books come from,” Taback told the Ventura County Star in 2007. (He moved from New York to California a few years ago to be closer to his children and grandchildren.) “The best ones look simple, but they are not simple to do.”

The illustrator Steve Brodner, who contributes to Tablet Magazine, agrees. “[T]his kind of simple is the hard eloquence we all strive for: nothing out of place or distracting,” he recently wrote in an appreciation of Taback posted on his blog. “The story, the design, the color, the humor all arrive together at one time, in one moment. This is art; the delight of seeing a piece by an artist in full charge of all the elements and delivering to you a wonderful world.” (And check out the comments on Bodner’s piece, from Taback’s childhood pals from camp and the Bronx, testifying to his menschlichkeit.)

Taback is quite ill with pancreatic cancer. He told me he didn’t want to be interviewed for this story because he’s concentrating on enjoying his family and finishing up his work. I hope he rallies. I hope every family is as touched and tickled by Postcards from Camp as I am. And I hope Simms Taback has many more books in him.

CORRECTION, March 10: Simms Tabak was born in 1932, not 1935, as this article initially stated. It has been corrected.

Slideshow image credits: Happy meal: James Glover II/vcstar.com. Book images and author photo: Penguin Young Readers Group.

Marjorie Ingall is a columnist for Tablet Magazine, and author of Mamaleh Knows Best: What Jewish Mothers Do to Raise Successful, Creative, Empathetic, Independent Children.

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.