Inheritance

First as cattle dealers and now as dairy farmers, the author’s family has long been defined by their cows. A trip back to their Bavarian homeland revealed this legacy to be more unusual—and fraught—than she’d ever imagined.

When my grandfather went to Jerusalem for the first time, in 1968, he was given the grand tour of the city, but after just two hours, he’d had enough. “Take me to see cows,” he said to the guide, or at least that’s the family legend.

I am the inheritor of a strange and somewhat obscure legacy. I come from a long line of Jewish cattle dealers. Our family history has been tied up with cows since at least the 19th century. In fading family photographs, you can see cows as well as ancestors. In my own childhood snapshots, I am smiling, hair cropped and parted, boots high, a calf sucking on my fingers.

I grew up in Hollywood, Florida, an affluent, largely Jewish suburb of Fort Lauderdale. My father still resides for most of the week on the family farm that my grandfather founded in Okeechobee, a two-hour drive away. When I was a child, my father came home one night a week and then again, for weekends, usually a few minutes before the sun set on Friday. Some 4,000 cows live on my family’s farm. There is much to do and the days are always long. But before my father leaves the house each morning in darkness, he makes sure to put on tefillin and say the shacharit prayers. He is, as far as I know, the only full-time Orthodox Jewish farmer in the United States.

Growing up, my friends were the daughters of cardiologists who took their children to Disney World. My summers were spent in the hot Florida sun, milking cows, sorting through tool sheds, cleaning calf cages, chasing after wayward heifers, and seeking the small comforts of air conditioning in my father’s Ford F-150.

In Germany, Jewish cattle dealers abounded. Considered the de facto bankers of the countryside, they were particularly targeted by the Nazi propaganda machine. My grandfather, born in 1907, had been groomed to take over the family’s prosperous cattle business, based in Ellingen, a small town in Bavaria, which had branches throughout the region. Then Hitler came to power.

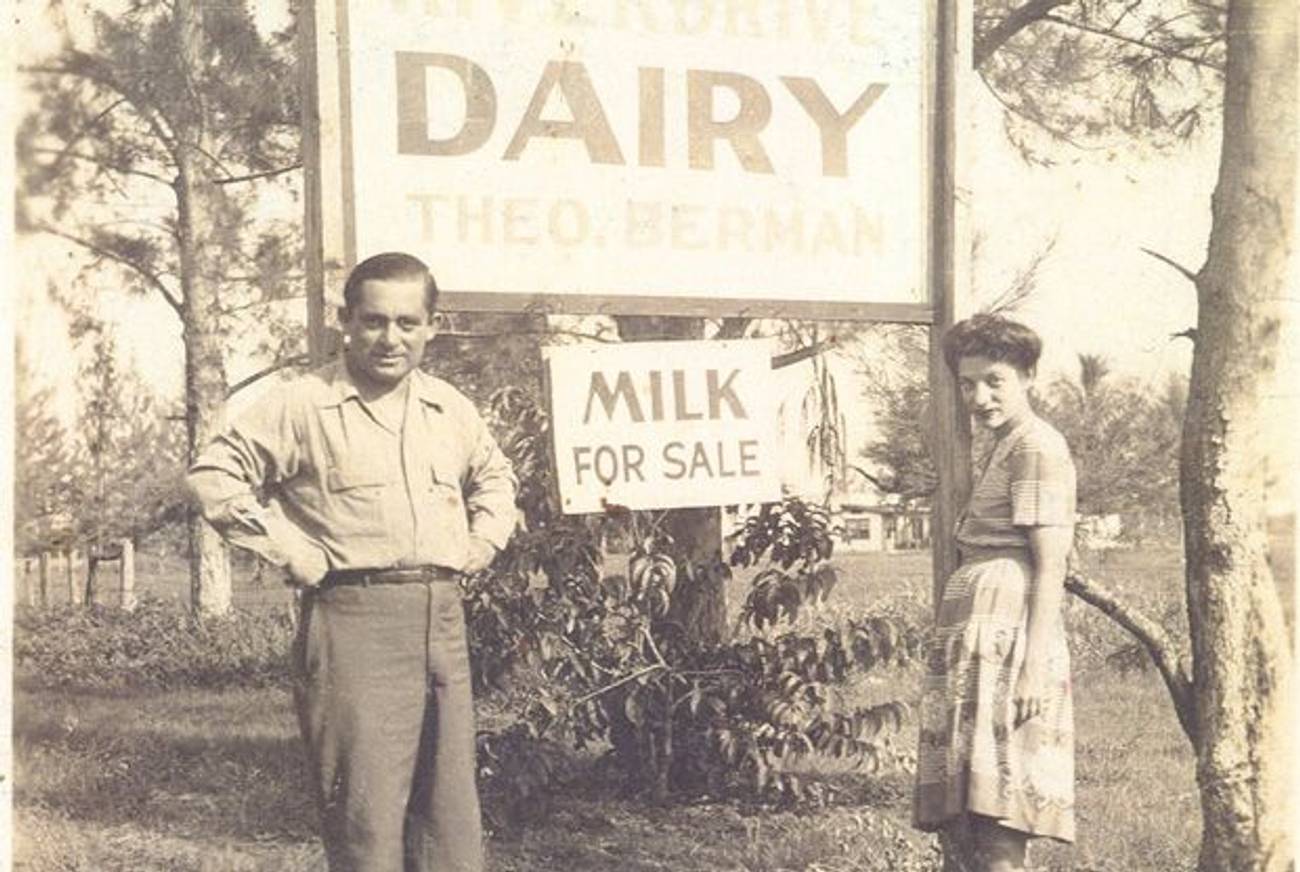

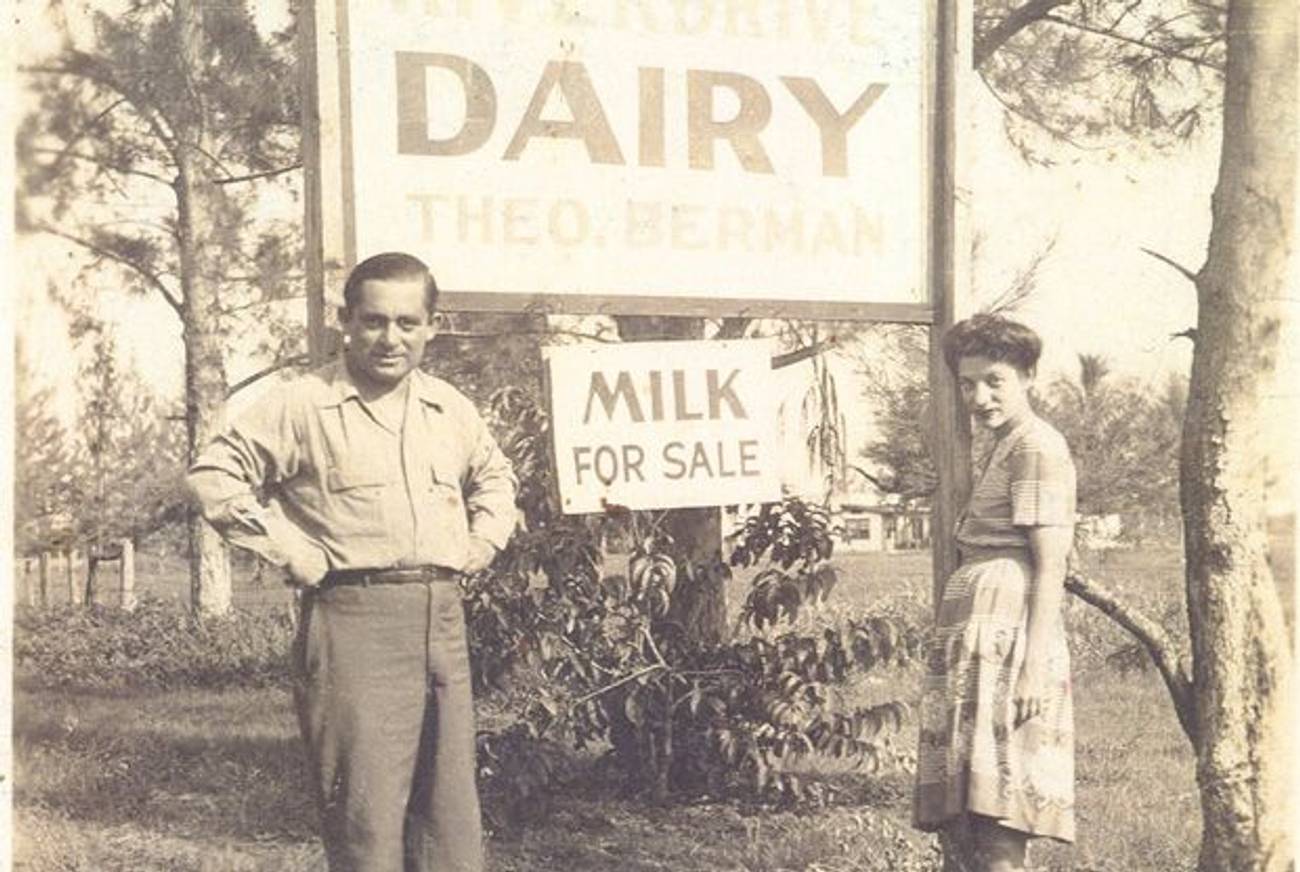

My grandfather escaped in 1938, and, after a few years in Cuba, he found refuge in Miami. When it came time to stake out his American dream, my grandfather turned to what he knew best. Though Bavaria is a long way away from Florida, Holsteins are Holsteins and farmers everywhere speak the same language. When he arrived in Miami, the area surrounding the city was still farm country. With an old pick-up truck, he slowly built a business buying and selling cows throughout the state. Around 1945, he decided to deviate slightly from the family tradition; he began to produce and sell milk, rather than just buy and sell livestock. It was a gradual process, and for a while, he did both simultaneously, establishing his first farm in Miami Springs, where the international airport is now located. “Cattle dealing was in his blood,” my father told me. “He was good at it, he loved it, and he could have made a very good living if he had continued.” But he made an intentional decision to shed his cattle-dealer past, a decision I learned more about when I visited his German hometown last summer.

I had been to Germany twice before: as a college student on a research grant, and later, as a journalist covering a conference in Berlin. But my interest in this period was always confined to my maternal side—my grandmother, who was born in Frankfurt, is a survivor of Bergen Belsen. My paternal grandfather, who never spoke about his childhood, died months before I was born and his wife—my grandmother—was a fifth-generation American who knew little of her late husband’s German past. Some photographs survived, and with them, small scraps of information about a small Bavarian town and a once-thriving business, but beyond that, we knew nothing. For the most part, my grandfather, an aloof figure, wiped a clean slate when he stepped onto American soil.

About 15 years ago, my brother went backpacking through Europe and decided to take a detour to Ellingen. There, he met a retired veterinarian named Bruno Buff who had heard of the Berman family from the farmers he worked with in the countryside. Buff also volunteered his time working in the city archives and took an interest in our family. In the years since, the family has stayed in periodic contact with him, mostly through Christmas cards.

But recently, Buff began corresponding more frequently. He told us about a German doctoral student named Stefanie Fischer, who had unearthed archival information about our family and was writing her dissertation on the relationship between Jewish cattle dealers and German farmers. He also sent us a copy of a book about the town’s Jews that had just been published by a ragtag group of amateur historians. He asked: Would we want to come to Ellingen for a visit? After some convincing, my father agreed; this would be his first trip to Germany.

Ellingen is a small, picturesque town just a short train ride from Nuremberg. We arrived from the United States, Israel, and England—more than a dozen in all, from my two-year-old nephew to a 70-year-old cousin who was born in Germany but now refused to speak the language. Ellingen boasted cobblestone streets; flowers spilling out of windowsills; the constant, somewhat maddening din of church bells; and a castle looming at the entrance of the town. Walking through the idyllic streets, I couldn’t help but think that ours was a particularly painful exile; Ellingen in the summertime seems too good to be true.

For most of us, it was our first trip to the town. My aunt was one exception; she had been to Ellingen in the 1980s, and as the story goes, she asked for directions to the Jewish cemetery. When the town’s German-speaking residents drew a blank, she started yelling, “Dead Jews! Dead Jews,” repeatedly at the top of her lungs.

Our arrival in Ellingen was a much talked-about novelty. Before World War II, the town had just a handful of Jewish residents, and now everyone—from the carpenter to the mayor to the innkeeper of a local bed and breakfast—seemed to know the name Berman. Buff, in his 80s, organized the three-day tour for us. He had fought in World War II, and won us all over with his warmth, kindness, and deep-seated regret. It was Buff who introduced us to the entourage of locals who accompanied us along nearly every stop: the retired baker, didn’t speak English, but communicated through strudels, thrusting baked goods our way with smiles; the town’s lawyer and self-appointed historian, who co-authored a book about the town’s Jews, despite what appeared to be no special affinity for Jews; and the makeshift archivist, a middle-aged, unemployed woman with bright orange hair who lived alone with her dog and spent hours sifting through the old papers, documenting the lives of the town’s Jews.

She told me that sometimes she walks the streets of Ellingen and sees the faces of the town’s Jews who have since vanished from its cobblestone pathways.

“They have become my friends,” she said with a sad smile.

In the years leading up to World War II, the German countryside was intensely poor. A farmer who wanted to buy cows was dependent on credit that he received from his local cattle dealer, not the bank. My family’s business, Berman-Oppenheimer, emerged as the leading cattle operation in Bavaria in the southeast region of Germany. On any given week, they would send upwards of 150 cows to market, an astronomical number for most German farmers.

“No other group was assaulted so much when the Nazis came to power,” Fischer, the German doctoral student, said of Jewish cattle dealers. “They became synonymous with ripping off farmers.” Nazis mythologized the struggling farmers in the heartland who worked the soil, and pitted them against the relatively well-off Jewish cattle dealers.

German municipalities tried to promote “Judenfrei” cattle markets, but many farmers boycotted them—not because of philo-Semitism, but because “Aryan” prices were deemed too high. For a time, German farmers prohibited the distribution of the Nazi newspaper Der Stürmer at their cattle auctions because it kept Jewish cattle dealers away.

Soon, Der Stürmer began to publish names of German farmers who continued to do business with Jews, branding them enemies of the state. “Jews had no soil,” Fischer explained. “They didn’t milk cows. They only traded. People looked at Jews as if they didn’t work.” The aging farmers Fischer interviewed for her dissertation told her that it never occurred them that the Jews couldn’t own land. “They saw trading as part of the Jews’ nature,” she said.

Walking the streets of Ellingen, our guides pointed to various buildings where Jews had once lived, and to the former synagogue, which is now a private home. The deputy mayor gave us a tour of City Hall and then invited us to show off his elaborate garden and in it, a tiny but ornamented garden shed.

“This comes from Bernard Berman’s house,” he said, pointing to the letters “BB” formed out of the wrought iron that now decorates the shed’s window sills. Bernard is the name of my great-grandfather, but also my own father’s namesake. “My father got it, but I’m not sure how,” he said.

We tried to pry more information out of him, but we didn’t make much headway. “My father bought it after the war,” the deputy mayor repeated several times in his limited English, surprisingly unselfconscious. It angered me; I waited for the deputy mayor to put on a work shirt, take the tools out of his shed, cut through the wrought iron, and return the decoration to its rightful owners—but of course my waiting was for naught. He never offered it, and we didn’t ask. In fact, he never invited us in inside his home.

Later, I asked my father about that moment; wasn’t the decorative piece his rightful inheritance? “I didn’t want it back,” my father replied. “I don’t need anything from him.”

One afternoon, we were sitting outside our hotel, enjoying the crisp Bavarian afternoon and sipping German beer in the cool shade when Hermann Seis, the town’s lawyer-turned-historian, came to greet us. My parents had corresponded with him via email, but this was our first meeting with a man who seemed to know more about our family than we did. Seis talked a great deal, but when he took a newspaper article out of his binder and started to pass it around, our large and somewhat unruly crowd sat in rapt attention.

What he passed around was a copy of Der Stürmer, dated December 1937, which none of us had ever seen. There, featured prominently on the front page was an article about my great-grandfather—“the greatest and most cunning of these Ellingen Jews”—who was arrested after he was accused of paying a farmer he worked with to murder a leading Nazi.

The article features three mug shots of my great-grandfather, presumably taken upon his arrest. We sat there, speechless, dumbfounded. My father had heard about an arrest once—not from his father, but from a distant relative who provided no details—but he didn’t know anything beyond that, and certainly not that it was front-page news. No one knew about the article’s existence. (It’s nearly impossible to get a copy of the paper in modern day Germany—wartime propaganda is kept under tight wraps by the country’s anti-Nazi laws—and so researchers need to jump through extensive hoops to prove their interest in the newspaper is purely academic.) To this day, we don’t know how long my great-grandfather sat in jail.

The article is long—more than 2,000 words in the English translation we commissioned—and it is extensive in outlining my great-grandfather’s alleged sins: betraying and displacing farmers, expropriating farms, destroying property, and causing poverty across the countryside. In the article, my great-grandfather is described as a “man of foreign race who corrupted farmers.”

“The Jew is a born criminal,” the article continues. “The strongest laws will not be able to change him.”

Later we learned that my great-grandfather was released soon after and fled with his daughter to London. He died there in 1943, but not before he settled his Ellingen city taxes from exile. If he were to return after the war, my great-grandfather wanted to be sure it would be as a citizen in good standing.

Presumably, my grandfather saw the article on the newsstands in Breslau, where he moved to establish another branch of the family cattle-dealing business in the mid-1930s. But he never mentioned it to his wife, children or grandchildren; we only heard of it for the first time over beer in Ellingen, church bells ringing in the background, from a man who was a stranger.

The next afternoon we visited the nearby town of Markt Berolzheim, home to another branch of the family cattle business. Hermann Bauer was our host. He had been mayor of the town for three decades and his father was the town’s leading Nazi politician during the war years. We talked in his garden and drank fresh apple cider. He asked my father how many cows he owned and when my father answered, the mayor blanched.

“That’s four times as many cows as in the whole village,” he said.

My father tried to downplay the success; he tried explaining how for Florida the farm is considered midsized. But it didn’t make much of an impact. Later, when we visited the home that once belonged to my grandfather’s cousins, the man who lived there shared with us a rumor that was floating through the town. “I heard that there is a man named Bill Berman who has more than 2,000 cows,” he whispered, wide-eyed, to my sister. Bill, of course, is my father, and the man’s estimate was off by half. Jews were reviled for their success in the pre-war years and here was my father being forced to return to the same situation; his discomfort—laced with pride, among other things—was palpable.

Before we left, my father took Fischer aside. “Tell the mayor we don’t sell cattle anymore,” he insisted.

Fischer obliged and the mayor nodded, as if in comprehension. But I’m not sure he understood what my father was trying to say. My father, and his father before that, were no longer traders. Family legend has it that until the day he died, my grandfather could look at a cow and remember where and how much he bought her for, even if years had passed. And though trading was clearly his passion, he wanted something else, felt it was essential to become something else. And here in Germany, my father—who has watched each of his five children choose career paths that have taken them away from the family farm—wanted to be sure that the distinction was clear.

Daphna Berman, a former Jerusalem correspondent for Haaretz, is now a senior editor at Moment magazine.