Inside the Camps

As anti-Asian violence surges, revisiting the history of Japanese Americans who were sent to internment camps during WWII

In 1942, Frances Adachi, a 20-year-old college student, was notified that she had to leave her life and everything she knew to relocate to a camp to the east. However familiar this story might first appear, Adachi wasn’t living in Nazi Germany nor even Europe. Adachi was an American living in Los Angeles and was sent to one of 10 camps in the U.S. that incarcerated Japanese Americans. Adachi had never been to Japan and was educated in the United States. Her only “crime” was being born to Japanese parents.

While U.S. internment camps certainly differed from Nazi concentration or labor camps, the disruption, xenophobia, and impact upon a generation of Japanese Americans should not be understated. The experiences of those incarcerated at Colorado’s Granada Relocation Center, also known as Amache, where Frances and her family were imprisoned, illustrate the lengths the U.S. government went to segregate Japanese Americans.

Today, the internment camp has been designated a National Historic Landmark, administered by the National Park Service; it includes some interpretive information, and is open to the public. Restoration projects throughout the camp are underway and visitors can download a map and virtual tour to make sense of what remains of the camp. Why should Jews, especially survivors of the Shoah and their descendants, commemorate the experiences of incarcerated Japanese Americans and visit Granada and other former internment camps? Especially in this time of increasing anti-Asian American violence, solidarity among communities is essential. Senior Rabbi Joe Black of Temple Emanuel in Denver, referring to the Talmudic admonition to take the words of Exodus 22:20—You shall not wrong or oppress the stranger, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt—to heart, asserted that: “This sordid story must be told and retold. Our collective history of persecution and displacement is a powerful reminder of the necessity to both remember the past and work to ensure that it never happens again. The shame of the Japanese-American internment camps that sprung up throughout the Western United States during WWII stands in stark opposition to this central Jewish value.”

The youngest of three children of Japanese-born parents, Tatujiro “Tom” and Tomiye Adachi, Frances earned her high school diploma in 1941 from John H. Francis Polytechnic High School in Los Angeles, which also graduated future Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley (1937) and Helen Gurley Brown (1939). Frances’ eldest brother, Kazumi, earned a bachelor’s degree in engineering and was working as a draftsman for the Summer Spaulding architecture firm; Tom supported his family as a gardener. The Adachis were practicing Methodists. Despite housing covenants restricting Asian Americans (as well as Jews and African Americans) from living in certain areas, the Adachis were building a quintessentially American dream—educating one’s children and providing opportunities for the future—until suddenly they weren’t.

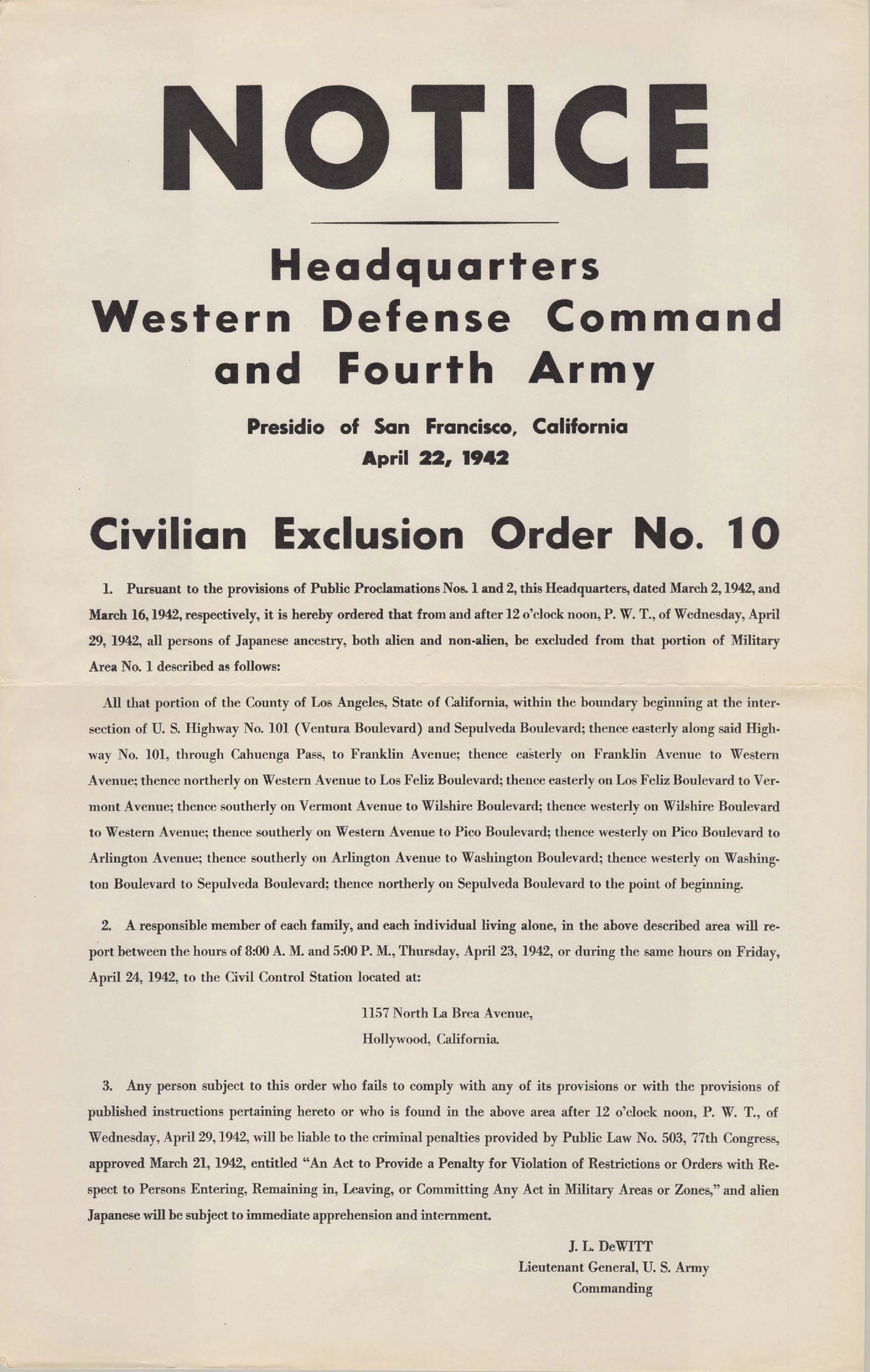

The change came quickly. Two months after the Japanese Imperial Navy bombed Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which designated much of the West Coast as a military zone, enabling the removal of persons of Japanese birth or descent ostensibly for the sake of national security. In 1942—79 years ago this week—Civilian Exclusion Order No. 10 went into effect; the Adachis were among the 120,000 individuals forced to leave school, employment, and homes and abandon property and possessions to immediately report to assembly centers and then to internment camps. The so-called “evacuees” were advised that they could only bring what they could personally carry, which typically amounted to a suitcase or two. In comparison, only 14,000 “enemy aliens” born in Europe were detained by the U.S. government during the same period, according to the Holocaust Encyclopedia.

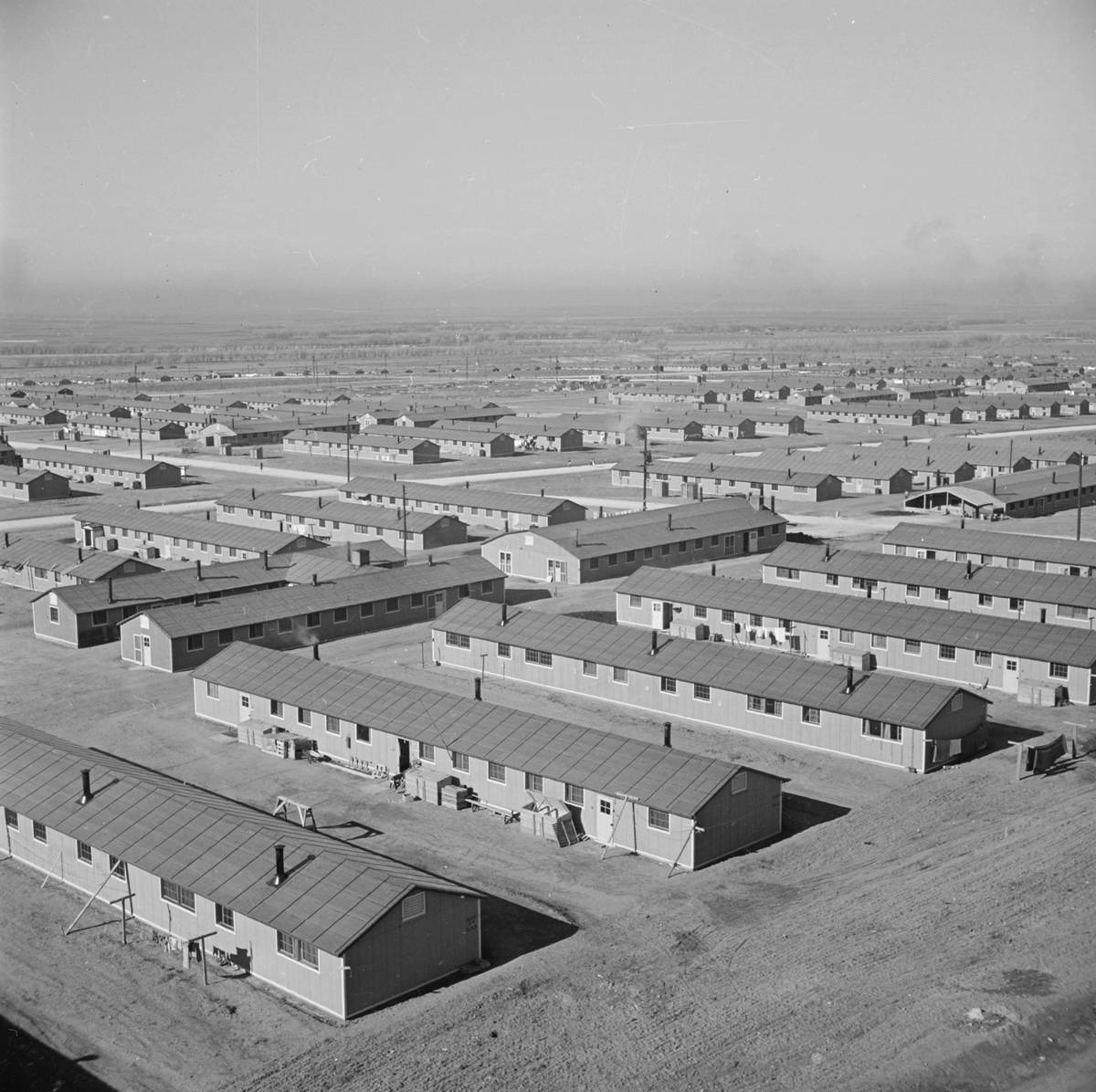

The Granada Relocation Center (also known as Camp Amache), 15 miles west of the Kansas-Colorado border, occupied 10,000 acres of arid prairie in which one square mile housed all 7,000-plus of those incarcerated. Like other families, the Adachis lived together in a 20-by-23-foot room outfitted only with cots, and used communal facilities for meals, bathing, and laundry. The facility, like the other such camps, was operated by the newly created War Relocation Authority and secured by armed military police posted in watch towers. At the same time, the WRA maintained a pretense of normal life. New “residents” received welcome packets that oriented them to the services and activities of the camp. Newcomers were advised to “meet your neighbors” (fellow prisoners). Children attended school and participated in Boy Scout troops. Men and women worked in camp clinics and kitchens, in the productive fields outside of the camp center, and in the camp’s screen-printing shop. Incarcerates planted gardens and celebrated holidays, worshipped and attended movies. At the same time, families lost businesses, property, and more. Residents were reminded by the WRA that it was their duty as Americans to conform to the demands of their incarceration.

The racism that existed toward Japanese Americans, even those incarcerated in camps, was palpable. The local community and U.S. Sen. Johnson (Colorado) resented what they perceived as “pampering” of the incarcerated families. Additionally, concerns were raised about providing education for incarcerated children. Under the auspices of the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Un-American Activities, the WRA was investigated, and a recommendation made for the U.S. Army to manage the internment centers, which did not come to pass.

Within the Jewish community, some Jewish leaders, especially on the West Coast, publicly opposed policies of Japanese American incarceration and resettlement. Rabbi Irving Reichert of San Francisco cautioned that Jews should be particularly attuned to prejudice given their own history of persecution in his sermon following the attack on Pearl Harbor. According to Cheryl Greenberg’s article “Black and Jewish Responses to Japanese Internment” in The Journal of American Ethnic History, the NAACP and the National Council of Jewish Women were the only two national civil rights organizations to speak out against Executive Order 9066. Greenberg recounts a 1942 statement of the latter group: “NCJW should take cognizance of the implications of the mass evacuation. Our committee recognizes … the wholesale evacuation of the Japanese without regard to their citizenship … disregards Article 14 of the Constitution.”

Indeed, two years later, despite previous decisions to the contrary, a Supreme Court decision, Endo v. The United States, ended incarceration for those individuals who had affirmed their loyalty to the United States, ruling that the WRA had no right to constitutionally incarcerate loyal U.S. citizens. Residents were advised in no uncertain terms to relocate eastward, separating them further from their prior homes and lives, although 86% of Granada internees wished to return to the West Coast if that were an option. Hotels were secured in East Coast cities and a number of religious organizations assisted with resettlement. The soon-to-be-released prisoners were admonished by the WRA to be “honest, industrious and loyal. … by being these things, you are helping to win this war,” and were curiously advised to “take pride in your Japanese origins.”

Frances Adachi and her parents initially settled in New York City while her brother Kazumi moved to Cleveland. Frances married Matao Tomimatsu, an American of Japanese descent who was himself incarcerated in a Utah camp. The family ultimately returned to the West Coast and parented two children. Frances died at age 87 in 2010.

Built hastily, the buildings in the Granada Relocation Center have crumbled in the more than 75 years since it opened, but there are efforts to preserve and share the history as the site works toward National Park status. The Camp Amache Preservation Society, founded and led by Granada High School dean of students and historian John Hopper, provides numerous online resources and is coordinating restoration efforts.

“You cannot take U.S. citizens’ rights away all because of their ancestry, race, ethnicity, color, or whatever the government would like to say about it,” Hopper told me. “Japanese Americans were treated completely and absolutely wrong during WWII—especially knowing all the Japanese American soldiers who fought and died defending the United States while their families were behind barbed wire guard towers and military police and had lost everything.”

And today, the sites may be particularly resonant, according to Scott Levin, regional director, Anti-Defamation League Mountain States Region: “The creation of a National Historic Site at Amache not only helps us remember, it provides an opportunity to confront our past to help dismantle the lingering xenophobia that allowed for internment and is still visible in the anti-Asian hate that has risen at alarming rates during the COVID-19 pandemic,” he told me. “Our generation and future generations have a moral responsibility to remember the shameful act of forcibly interning Japanese Americans and people of Japanese ancestry on American soil.”

Naomi Sandweiss is the author of Jewish Albuquerque, and a past president of the New Mexico Jewish Historical Society.