Jewish Burials Without Mourners on Staten Island

Coronavirus victims make their way to Mount Richmond

The aron arrived on the back of a white pickup truck, and two men in yellow Tyvek suits unloaded it onto a gurney. Hours of a now-misting rain had loosened the ground into a swamp, and the space-suited workers struggled to push their cargo through a morass of wet mud as the few attendees—a rabbi, three cemetery workers, a young member of the local chevra kadisha, and a couple of writers—observed the casket’s turbulent final journey. No one present knew very much about the person inside.

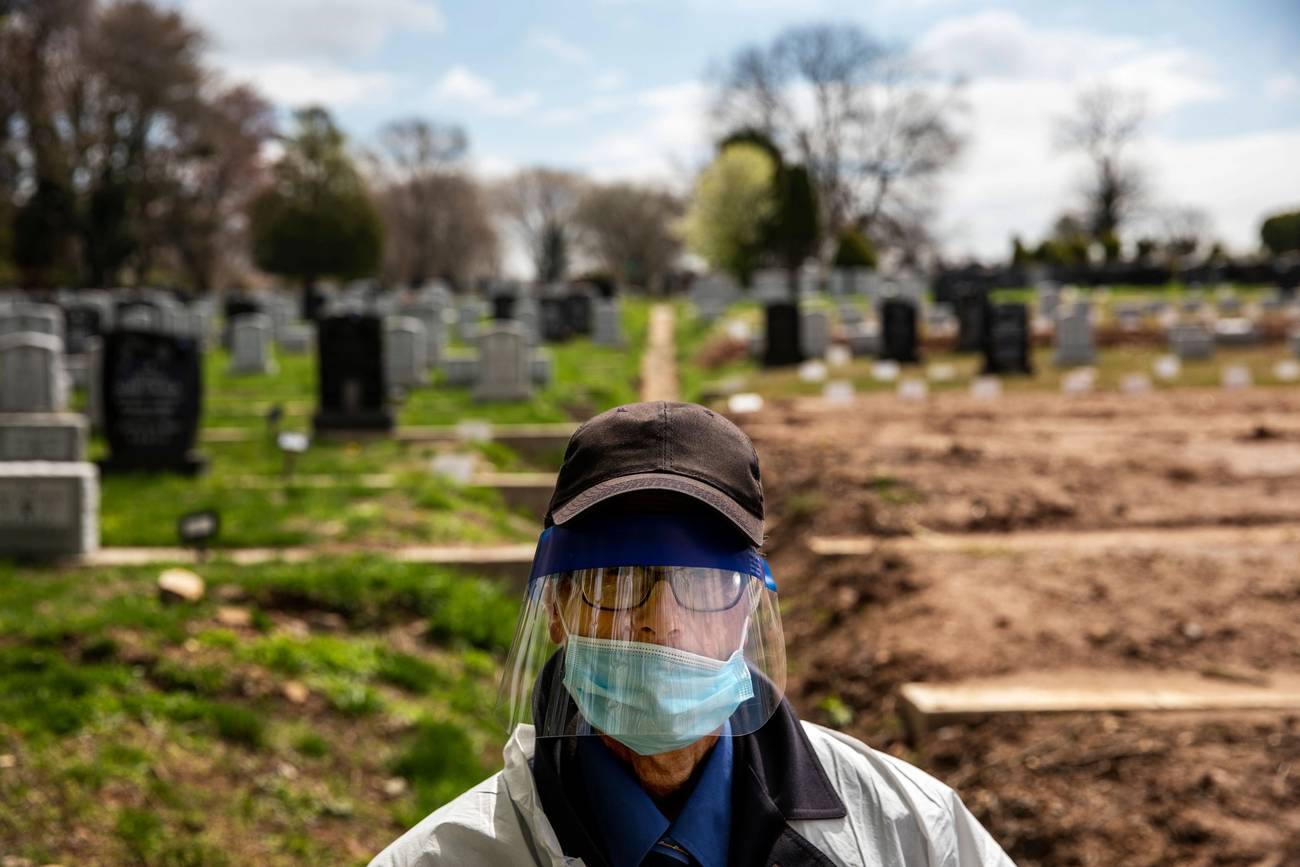

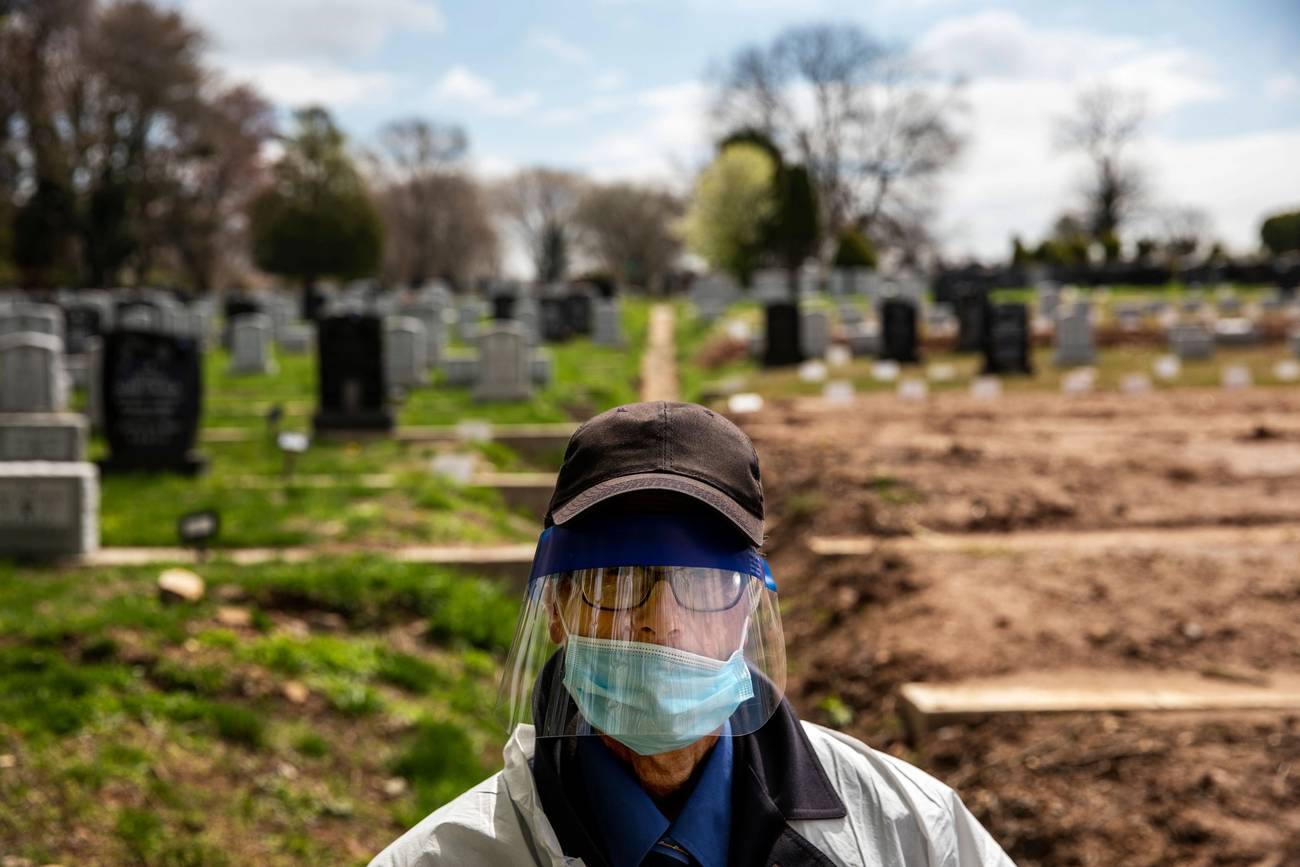

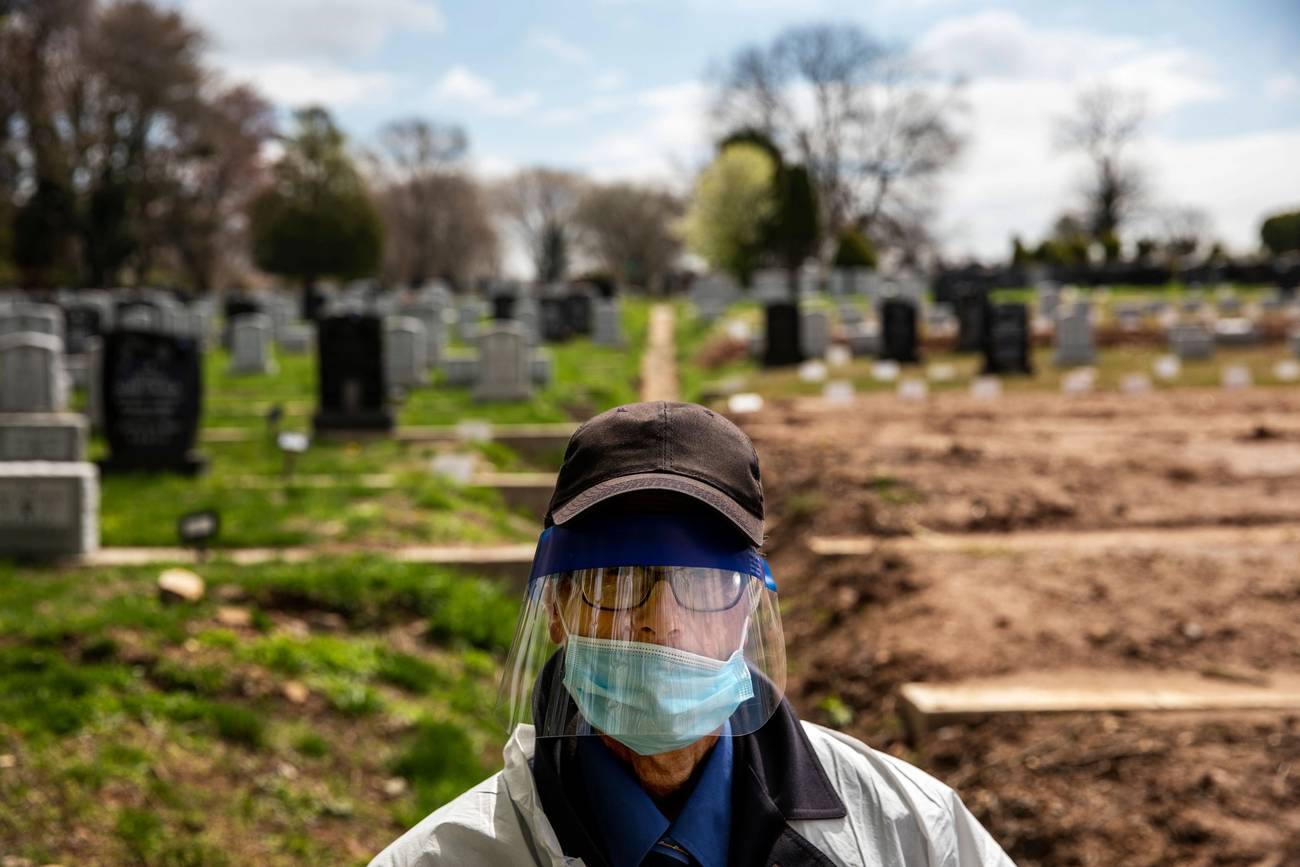

“We are burying a young man,” began Rabbi Shmuel Plafker. Rail-thin, the rabbi wore a black baseball cap, circular tortoiseshell glasses, heavy tan leather construction boots, and a suit and tie under his white full-body Tyvek. “Seventy years old. Dead of COVID. Never married.”

In his nearly 30 years as the rabbi at the Hebrew Free Burial Association’s Mount Richmond Cemetery in central Staten Island, Rabbi Plafker has seen forests gradually turn into rows of caskets that he has personally committed to the earth. Lately, the transformation of virgin ground to coffins has been happening more rapidly. “We did 187 funerals” between March 1st and April 30th, said James Donofrio, the HFBA’s funeral director. Before the plague, the usual monthly number was about 30.

Below the fresh grave were a half-dozen rows of low concrete embankments that will serve as foundations for burial monuments. Before the coronavirus hit, HFBA believed it would take several years to fill these rows. Now they might be occupied within a matter of months.

At the beginning of the epidemic, HFBA ordered a small mortuary cooler that would have increased on-site storage from seven to 11 people. “We thought that was gonna do it,” Amy Koplow, HFBA’s executive, recalled in a mid-April interview. But the need escalated so quickly that the organization soon obtained a 40-foot refrigerated trailer about the size of a shipping container. Its generator hummed through the service, which lasted a little over 10 minutes. “The phone’s been ringing nonstop,” Koplow added. “Death after death after death after death. And every story is sad.” She said the nonprofit organization has about 10 full-time employees, depending on how you count.

“We come from earth, we go back to the earth,” Rabbi Plafker said at the graveside, the aron now in place for eternity after dangling from a metal arm over the awaiting trench. “The wood will disintegrate over time ... The body will return to the earth ... The soul will return to the Almighty.” Plafker read Psalm 23 in English and Hebrew from a much-used paperback Art Scroll volume. Then: “You are the judge of truth ... Your judgments are accurate and true, even if we as human beings cannot comprehend them.”

The earthmover then pivoted left and right, smoothing over the damp mud with the back of its scoop. There were no shovels–none of the attendees could pour earth on the aron, as would happen at any Jewish funeral held in less pestilential times. There was no Kaddish, no family in attendance.

A week earlier, when I had spoken to him by phone, I asked Rabbi Plafker how many funerals he had conducted during the epidemic in which there had been no other mourners present. He consulted a log book, and then counted aloud as he numbered the dead, people that he and he alone had buried, one by one: “66 burials that no one came to. Blank.” Though he added: “I may have called family in some of these cases.”

At the grave Plafker continued, “We do not know much about this gentleman we are burying today. In fact, we know almost nothing. God alone knows what this individual did. But we ask God to reward him in the next world.”

The rabbi almost mumbled at times, but his voice never lost feeling. Not a single word was uttered with indifference. He did not weep, but it was his duty not to weep—instead, he must shoulder a burden of grief that no one else can or will carry, then move on to the next burial. During a funeral with attendees or with family on the other end of a phone call, Plafker said, “I ask, take two minutes to tell me who they were, and briefly discuss who this person was. This was a human being. This was a fellow Jew. I want to hear something about that person.” He recalled a dermatologist who overcame anti-Semitism to earn a medical degree in the Soviet Union, and a 92-year-old who went to the racetrack even in the final year of his life, and a mail carrier who loved fishing and “only caught kosher fish.”

But today, Rabbi Plafker knew nothing—just a first name, a last name, a father’s name, an age, a cause of death, and the fact of his body having gone unclaimed. The dead man was somehow both no one and everyone, in addition to whatever other, now-unknowable things he might once have been. After the El Malei Rachamim, in which the mumble broke into clear and aching high notes that rose above the ambient bird song, Rabbi Plafker concluded the service: “May this special human, this special Jew, rest in peace.”

Rabbi Plafker, who lives in a Jewish neighborhood in central Brooklyn, received smicha at the Rabbi Jacob Joseph yeshiva, “actually known as the Mother Yeshiva,” back when it was still on the Lower East Side. He later got a secular college degree and went into business. He became the HFBA rabbi through a personal contact during a brief spell of unemployment a few decades back—he says that at the time he had never really conducted a funeral before.

Because a strict code of moroseness would in fact be poor tribute to the dead, Plafker’s rabbinic wit isn’t wholly wasted on these acres of departed congregants. Thus he offered a breezily profound meditation on bald spots, his being a bit fuller-blown than mine—“grass doesn’t grow on busy highways”—immediately followed by an arresting history lesson; an invitation to picture an earlier and no less surreal train of death that had ended almost exactly where we walked.

“Twenty-two Triangle Fire victims are buried here,” he told me. Nearly all of the dead are women. Back in 1911, their bodies would have arrived in Staten Island by boat, as there were no bridges to Brooklyn or to the mainland. A long caravan to this innermost point in New York’s most isolated borough was required to give these people, who had died in unfathomable fear and agony, whatever solace a Jewish burial could provide them. “Getting here from Manhattan was a full day. They came on horse-drawn carriages. Imagine what that must’ve been like—one, after another, after another.”

HFBA purchased the land used for the Mount Richmond Cemetery in 1909. Since then, it has been the burial option of last resort for New York metro area Jews. In some cases, a family must prove to HFBA that they do not have the resources to bury their dead loved one anywhere else. If there is no family, and if a body goes unclaimed from the medical examiner’s office, a county official called a public administrator effectively becomes the dead’s legal next of kin.

HFBA, which is in constant contact with area public administrators investigates the background of any unclaimed individual who might potentially be Jewish, sparing them cremation or burial in a potter’s field if a Jewish identity can indeed be established. Once the bodies are released to HFBA, they are taken to Mount Richmond, which has a tehara facility that includes a mikvah, staffed with men and women’s chevrei kadisha that conduct the final ritual purifications. Until March 12, a volunteer minyan would sometimes be convened to say Kaddish over the dead, who would still get an El Malei Rachamim and a reading of Psalm 23 even if Rabbi Plafker and the gravediggers were the only ones around to hear it. In those cases—any of those 66 in which there were no others present—Rabbi Plafker fills the silence by reciting psalms as the aron is covered.

What are you thinking during a funeral? I asked the rabbi during the 20-minute break between burials. “That I’m under pressure of time,” he replied. In the coronavirus era, when there have sometimes been a half-dozen burials in a single morning, an HFBA funeral can’t really go more than 15 minutes. Perhaps it shouldn’t go any longer than that anyway—the ceremonies are expansive as only something instantaneous can be. “Try to feel for the people” Rabbi Plafker told me when I asked him how he could bury so many people without losing sight of the human element. “Try to feel their pain. Don’t prolong it—don’t schlep it out, if you know what I mean. Do it with dignity. Do it respectfully. It’s someone’s father, mother, brother, sister being laid to rest—someone they’ll never see again. They’ll never hold them, never kiss them, never argue with them—all of what makes life what it is.”

In addition to being HBFA’s funeral director, Paul Donofrio runs a funeral home in south Brooklyn, meaning he had some role in roughly 400 burials during the month of April; a number that we, unlike Donofrio, have the luxury of not needing to comprehend. A tzaddik by any definition, Donofrio isn’t Jewish. Even so: “He knows more about Jewish burial than most people in Borough Park,” Rabbi Plafker explained. “None of us can feel anything,” Donofrio told me at the cemetery. “We just have to do what needs to get done and then we’ll figure out what to do afterwards.” In a later phone interview, he clarified: “The ‘afterwards’ is gonna be that most funeral directors are gonna need some form of counseling.”

Mourners who do attend an HFBA funeral at Mount Richmond must now stay in their cars, a safe social distance from the actual grave. From their vehicles they squint at a foursome of white- and yellow-suited space aliens surrounding the small earth mover. Rabbi Plafker communicates with them by phone. So it would be for the next burial. We walked to the outer edge of the cemetery, where two cars worth of mourners were waiting, including the wife of the deceased, who would one day be buried next to him.

“Can you hear me?” Rabbi Plafker asked, speaking into his phone. “I can hear you!” the widow replied, from a car about 100 yards away. I never saw her face. “He went away April 1,” she said, explaining her late husband’s disappearance into hospitals and nursing homes, places now beyond the reach of just about any outside human contact. “I never saw him again.”

Toward the end of the burial, Rabbi Plafker recalled a Yiddish saying to the woman: “A gitte bitte—He should be a good intermediary in heaven,” someone who could plead with God for this plague to end.

I asked Rabbi Plafker to further explain the phrase during our slow walk back to the cemetery entrance, toward the mud tracts that would fill far earlier than anyone had once expected. For the entire year, Rabbi Plafker explained, Jews pray directly to God. But there was a tradition of visiting the graves of loved ones before Rosh Hashana, to request just a little extra help. “I always say on Rosh Hashanah, we’re asking the landlord to extend the lease another year. No one has a guarantee.”

But a Jewish burial ritual is a guarantee of sorts—it at least contains the certainty that the dead will be prayed over, that their bodies will remain intact, and that they will be granted the ultimate kindness of the tahara, cared for even in death, regardless of their earthly circumstances, which have finally ceased to matter.

Every funeral at Mount Richmond is its own victory against the abyss. The people buried here will not have simply vanished into the earth. So the lessons one might draw from conducting scores of coronavirus burials are not wholly discouraging. “You have to appreciate every single day,” Rabbi Plafker told me. “Don’t take your loved ones for granted. Tell them you love them. Appreciate what God has given you. We have so much: a roof over our heads, food. Most of us can feed ourselves. We have clothes to put on. Maybe we didn’t buy new clothes for Pesach, but thank God we have clothes to wear. When you think about it, there’s so much to be grateful for.”

Armin Rosen is a staff writer for Tablet Magazine.