Discovering My Connection to Einstein, and Why I Have Maimonides’ Nose

In his new memoir ‘Free Spirit,’ Joshua Safran turns to the library to understand the Jewish heritage his mother can’t explain

I know now that my family tree is adorned with rabbis and Hebrew novelists, Yiddish auctioneers and shtetl folk healers. But, as a kid, I didn’t know a thing about it. I didn’t even know I was Jewish. My mother, Claudia, pulled up her roots as a teenager and came west to San Francisco in the Summer of Love, trying to find a new family—one based on a shared vision of communitarian love, not tribal bloodlines or ancient texts. She still hadn’t found what she was looking for by the time I was born at the end of the Vietnam War, and my early childhood was spent wandering the American West in search of an elusive utopia.

By the time I was ten we had hitchhiked for thousands of miles and befriended hundreds of remarkably strange people. My mother and I had danced around bonfires and lived in vans, buses, and an ice cream truck. Some nights we slept blissfully under the stars, others I lay awake frightened by the howling of wolves.

Our quest for utopia stalled out in rural Washington State when Claudia married Leopoldo, a former Central American guerrilla fighter who brought with him demons from the Salvadoran civil war and a serious drinking problem. My mother was convinced he was the messianic revolutionary hero she had foretold in clairvoyant visions. I was pretty sure he was going to kill us.

In the summer of 1986, we moved to a temperate rainforest on one of the San Juan Islands. Leopoldo told us he was going to build us an ancient Egyptian-style pyramid to live in, but his plan failed when he threatened to kill the property owner. As the rains winter fell, we found refuge in a dilapidated little apartment in the town of Stanwood, Washington.

That winter brought wild storms howling in off of the Puget Sound, followed suddenly by calm and open skies. Like the alternating rhythms of rain and sun, I accepted the rounds of violence and reconciliation in my home as normal. Not ideal, not pleasant, but reliable and certain. The steady cadence of Leopoldo and Claudia marching together as husband and wife.

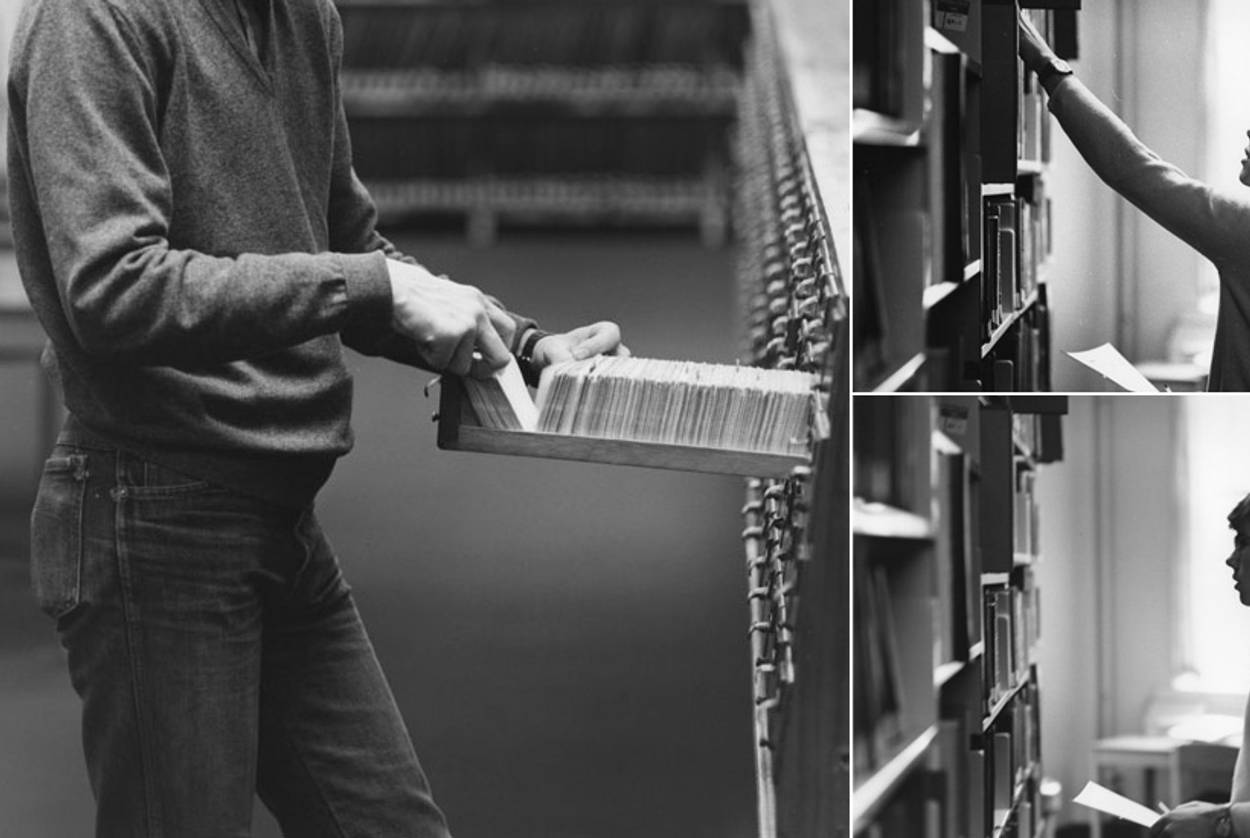

Home was bearable in times of peace, but in times of war I sought political asylum at the Stanwood library. There I began cruising the Dewey Decimal System for meaning and inspiration. But I didn’t just leap into the beige metal stacks with my eyes closed. I had a destination in mind—the neighborhood of call number 296. Judaism. Whatever that was.

My research was the fulfillment of a prophecy made back on Cultus Mountain, before the advent of Leopoldo. Climbing the trail one evening we passed the cabin of a neighbor named Ray and noticed it glowing through the darkening mist. Ray rarely ventured up from Seattle, so we stopped in to say hello. Ray looked like a fisherman from the back of a National Geographic map of Crete and exhibited an appropriately Mediterranean hospitality.

He welcomed us in with one of those thick Back East accents that vaguely reminded me of Grandma Harriette.

He was originally from New York, he told us, and wanted to know where we were from.

“The Bay Area,” replied Claudia.

“No way,” Ray said. “I don’t believe you.”

“Why not?”

“You’re Jews, right? Ain’t no lantzmen from San Francisco.”

Claudia laughed. “Yeah, we are Jews. How did you know?”

“Your kid’s got a rabbi’s nose.”

They laughed and spoke of ancient times. Places and people east of the Mississippi. Chicken soup and strange holidays. Ray’s whole body shook when he laughed, and he concluded his story with: “So I bet I was the only Italian kid in Brooklyn who had not one, but two bar mitzvahs.”

Claudia and I stepped back into the mist, and a faint light of recognition flared in my mind. We weren’t totally alone in this universe. There was a name for us. A name for why Grandma Harriette said “Who really knew?” when I asked her where we were from. A name for being Russian, Lithuanian, and German, but cringing at the memory of the Russians, Lithuanians, and Germans. The name explained why my grandfather was blacklisted by McCarthy and forced to drag his family from place to place. And this same name must be the reason we continued to wander, searching for a promised land, while we avoided Christians, read books, and gesticulated wildly with our hands. A name that explained it all. But I’d forgotten what it was.

“Claudia, what was that thing he said we were?”

“What thing?”

“There was something he knew we were. Because of my nose.”

“Oh, Jews?”

“Yeah. What is that?”

“I never told you we were Jewish?”

“No. What is it?”

“Jews, you know. Like Einstein, Freud, Marx.”

Being my mother’s son, I knew who those men were. But I didn’t see the connection. “Like we’re related to them?”

“Sort of.” And then she gave me a very Jewish answer: “You know, Joshey, I don’t exactly know what it means to be Jewish. We’ll have to go to the library and look it up.”

I was in the library now, riding the reading room through space and time, discovering that I was part of something. Something profound. I was the descendant of an ancient tribe that had emerged from the mists of prehistory to introduce the world to God, to write the Bible, and to shine unto the nations like a beacon of righteousness. We had been scattered to the wind, driven to the four corners of the Earth. Oppressed and demeaned time and time again, yet we wandered on, excelling in isolation wherever we went. We didn’t need to be normal like everyone else; we were Jews. When the library closed, I walked through the darkness, an only child no more. Now I knew I descended from the seed of Jacob, and somewhere out there were a million of my nameless brethren, clinging to diasporic rocks just like me, but thriving nonetheless.

“I was flipping through the pages,” I whispered to my mother in the rank, lutefisky darkness of Inga’s sitting room. “And there was a drawing of Maimonides. He looked just like me, but with a beard and a turban. The same face, the same rabbi’s nose.”

“He spoke to you across the generations,” Claudia assured me.

“Yeah . . . he did,” I agreed with her for once.

My mother whispered to me about our family. My great-great-grandmother Rivka was a folk healer in the forests of Russia. My great-grandmother Eta called the mounted police Cossacks and threw her body in front of the Nazi ships unloading in Boston Harbor in 1939. And then Claudia told me that somewhere out there I might have a half-brother. When she was a teenager she’d dated a Colombian Marxist revolutionary and had gotten pregnant. She’d given the baby up for adoption in New Jersey and had never seen him again. It was 1987 now, so that would make him twenty-three. My mother shook her head and shrugged. It was all part of an old world she’d forgotten about so long ago.

But it was a brand-new world for me. I lay in bed that night still immersed in my voyage of self-discovery. Though I sojourned at the very end of the Earth, the blood of Abraham still coursed through my veins. And beyond the horizon, in the wilds of far-off New Jersey, that same blood might course through the veins of a brother as well. Maybe someday this brother would find me, grasp me by the arm, and pull me up out of this broken world where screaming and smashing were considered normal. Maybe I’d finally go home, wherever that was.

Adapted from Free Spirit: Growing Up On the Road and Off the Grid, by Joshua Safran. Published by Hyperion Books, a division of the Hachette Book Group. Copyright 2013. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.