The Kings of Suburbia

William Levitt and Joseph Eichler both pioneered suburban development. But one fought for fair housing, while the other refused to integrate his communities.

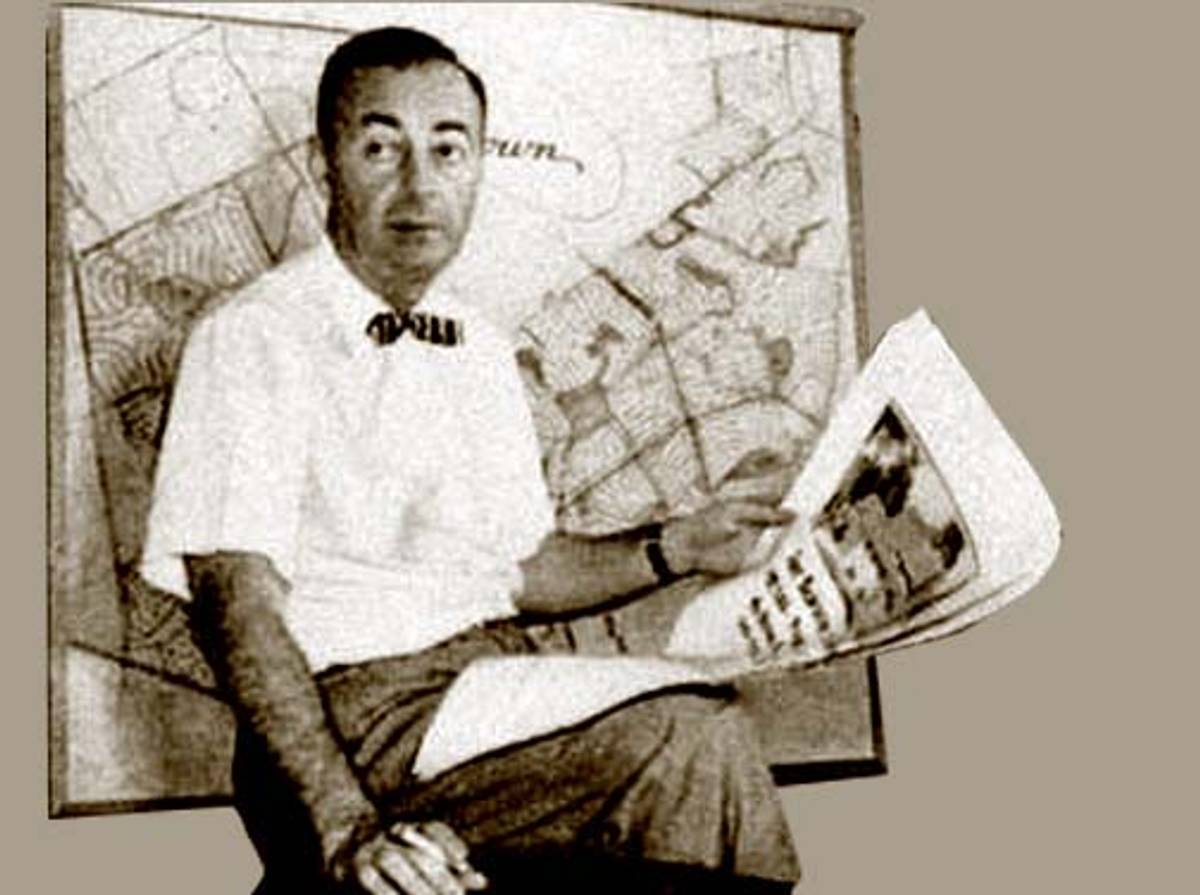

Suburban housing developments, simultaneously loathed and loved, began in the mid-20th century. Two of the major figures who built these developments were William Levitt (1907-1994) and Joseph Eichler (1900-1974), both sons of New York Jewish immigrant families. Yet the communities they created differed in one very important respect—one whose legacy endures to this day: While Levitt & Sons built “whites only” communities and refused to integrate their developments, Eichler and his son Ned fought just as hard to oppose discrimination in housing, even helping to write California’s fair-housing law.

Joseph Eichler was born in New York at the dawn of the 20th century. After attending New York University and marrying Lillian Moncharsh in 1925, he relocated to Northern California, where he worked as a food broker for his father-in-law’s wholesale dairy business for the next 20 years. After the family moved to a rented home designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, Eichler was so enamored by Wright’s architecture that in 1949 he decided to enter the residential housing market. Now known as the epitome of California Modern, Eichler’s open concept homes were designed by architects and typically featured inner courtyards, radiant heating, and a profusion of glass. Due to a streamlined building process, an Eichler home could be purchased for just under $10,000. Ned Eichler, Joseph’s son and business partner, described Eichler’s buyers’ as “having upper middle-class tastes with lower middle-class incomes.”

Seven years younger than Eichler, William Levitt was also born in New York City, the grandson of a rabbi. Levitt’s father, Abraham, dropped out of school at age 10 but educated himself to the point that he earned a law degree, specializing in real estate law. William attended Brooklyn’s Boys High School and New York University, although he didn’t graduate. In 1929, Abraham started a real estate firm and hired his son as president. The same year, William married his first wife, Rhoda Kirshner, with whom he had two sons.

In the early 1940s the Levitts won contracts to build housing for defense workers, and while William learned construction as part of the Navy’s Seabees battalion in Hawaii, his father and brother began purchasing land on Long Island for future developments. After the war, the Levitts began mass-producing inexpensive housing developments that included shopping centers, parks, and schools. The Levitts also focused on streamlining manufacturing techniques by using a single floor plan, eliminating basements, and employing nonunion labor. As The New York Times later recounted in his 1994 obituary, Levitt described the firm’s building process as a “reversal of the Detroit assembly line ... There the car moved while the workers stayed at their stations. In the case of our houses, it was the workers who moved.” The three-bedroom homes were available for under $7,990 with almost no money down—that is, if you were Caucasian.

Levitt & Sons sold thousands of homes to white Americans in developments called Levittown in three states (New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania). The firm’s success coincided with the postwar baby boom, suburban migration, and the availability of the GI Bill. Soon William Levitt was crowned “King of Suburbia.” However, throughout all Levitt & Sons communities, contracts included a clause stating that homes “could not be used or occupied by any person other than members of the Caucasian race” and covenants ensured that houses would not be resold to African Americans.

Furthermore, Black buyers, even veterans, did not have access to the same mortgage terms as whites securing loans under the provisions of the GI Bill. Since the administration of the GI Bill was locally controlled (thanks to congressional Southern Democrats), African American veterans often had to produce hefty downpayments and pay higher interest rates than whites to purchase a home. Edward Humes notes in Over Here: How the GI Bill Transformed the American Dream: “Shamefully, Levittown, like many other heavily subsidized suburbs ... took the concerns of segregationists to heart ... walling off this new American dream from black and brown veterans and other buyers of color.”

The practice of redlining—designating parts of communities as too risky for mortgages and thereby segregating them—also barred Blacks from suburban home ownership. These practices left African Americans frozen out of affordable postwar housing due to “James Crow” policies, notes Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Isabel Wilkerson.

William Levitt’s view on the issue was clear. “As a company, our position is simply this,” he said. “We can solve a housing problem or we can try to solve a racial problem, but we cannot combine the two.” Since federal fair-housing legislation was not enacted until 1968, Levitt’s policies stood.

In contrast, Eichler & Sons sold homes in their developments to Asian Americans in 1949 and African Americans in 1954. Eichler salespeople were advised that “selling without discrimination would be our policy from now on, that we would not seek any publicity for it but neither would I continue to employ anyone opposed to it,” recalls Ned Eichler in his book Fame or Fortune. Joseph Eichler told white homeowners in his communities who were concerned about their Black neighbors’ impact on home values: “I would be glad to buy anyone’s house back. We sold it too cheap anyway.” In fact, Eichler did buy back at least one home from a white homeowner and resold it again quickly.

In 1958, the Eichlers resigned from the National Association of Home Builders when the organization refused to support a nondiscrimination policy on the heels of a Sacramento, California, court decision to end discrimination against African American buyers. Ned Eichler explained his father’s position on the issues of profit and progress. “I think that builders cannot evade the fact that what they’re doing is going to have an impact on the whole community, even on the nation, for a long time and they cannot simply say, ‘Well, I’m just a businessman. I’m here to make a buck.’”

In 1961, Ned Eichler was selected to chair California Gov. Edmund “Pat” Brown’s Commission on Housing Problems. While a California law banning housing discrimination passed in 1963, the Rumford Fair Housing Act was repealed by ballot initiative in 1964.

Meanwhile, Levitt refused to budge on his whites-only sales and occupancy policies. In the early 1960s, tensions rose when Levitt built a whites-only Belair housing development in Bowie, Maryland, 18 miles outside Washington, D.C., featuring air-conditioned colonial homes for $18,500. The issue even came to the attention of President John F. Kennedy, who signed an executive order in 1962 to prevent discrimination in developments that received federal financial assistance. Despite the pressure and a summerlong protest that included the Congress of Racial Equality, Jewish War Veterans, and members of local synagogues, Levitt doubled down on his policy, arguing that the company was simply following local customs. In a 1963 statement, Levitt insisted that he would not open the Belair community to Black buyers until all other Washington, D.C., area developers agreed to do the same.

It is difficult to say how Levitt and Eichler’s Jewish identities affected their views on segregation. Levitt was generous to Jewish and Israeli philanthropic causes. In Fame or Fortune, Ned Eichler, who ironically served as president of Levitt’s company in the 1970s, explains:

I know little about Levitt’s relationship to being Jewish ... but I know a great deal about my father’s. He was not a reflective man, but his words and even his actions demonstrated his conviction that a Jew who inherited or earned a lot of money had two responsibilities. First, he should help those in need. Second, he should cultivate himself. When in his opinion someone shirked one or both of these responsibilities, he would remark with contempt, “That a Jew should act that way.”

Ultimately, Levitt and Eichler, both visionaries with strikingly similar backgrounds, made radically different decisions in terms of their business policies and larger role in society.

What is the legacy of Levitt’s refusal to integrate his developments? African Americans missed the opportunity not only to own a home but to build equity and generational wealth as a result. Levitt and Eichler homes have increased in value many times over with one-time $10,000 homes currently valued somewhere between half a million to several million dollars.

Strikingly, 75 years later, some communities that began segregated remain that way. In New York’s Nassau County, home to Levittown, 10% of the population is African American while in Levittown in particular, African Americans make up only 0.9% of the population, according to the 2010 Census. Humes notes, “While the children and grandchildren of white veterans enjoy the benefits of all that government-subsidized home equity, black and Hispanic home ownership rates remain stuck at below 50%.”

Hardest to quantify is what suburban housing discrimination cost all Americans in terms of the societal and cultural costs of ongoing segregation.

Naomi Sandweiss is the author of Jewish Albuquerque, and a past president of the New Mexico Jewish Historical Society.