Teaching Kids About the Holocaust: How Young Is Too Young?

‘Let the Celebrations Begin,’ an acclaimed and controversial Australian children’s book, raises questions about Holocaust education

Let the Celebrations Begin has all the hallmarks of a successful children’s picture book: simple language with just the right amount of repetitive phrasing, watercolor illustrations, grumpy-yet-charming elders, and wide-eyed children who must learn to accept the difficult realities of their small universe. But—to paraphrase that very Jewish question—there’s one thing that makes this picture book different from all other picture books: The story takes place in a concentration camp on the eve of liberation, and all the characters are starving.

The book was originally published to great acclaim, and some controversy, in Australia in 1991, when I was growing up in Melbourne. Author Margaret Wild and illustrator Julie Vivas are both beloved and prolific contributors to the corpus of Australian kid-lit. There’s not a bookseller Down Under who doesn’t recommend Wild’s Harry & Hopper; and Possum Magic, illustrated by Vivas, is the country’s unofficial national picture book.

There was a copy in my school library, which I read many times; I must have been around 9 when I first read it, and I returned to it often as a teenager. Let the Celebrations Begin has been out of print in the United States for over a decade, but this September it will be republished. (Which is great, because it means I can finally stop scouring secondhand bookstores for battered, decommissioned library copies.) But even after more than 20 years, the book still raises the same questions it did when it first came out: How young is too young to learn about the Holocaust? And how frank and explicit can a book about the Holocaust be while still being appropriate for children?

***

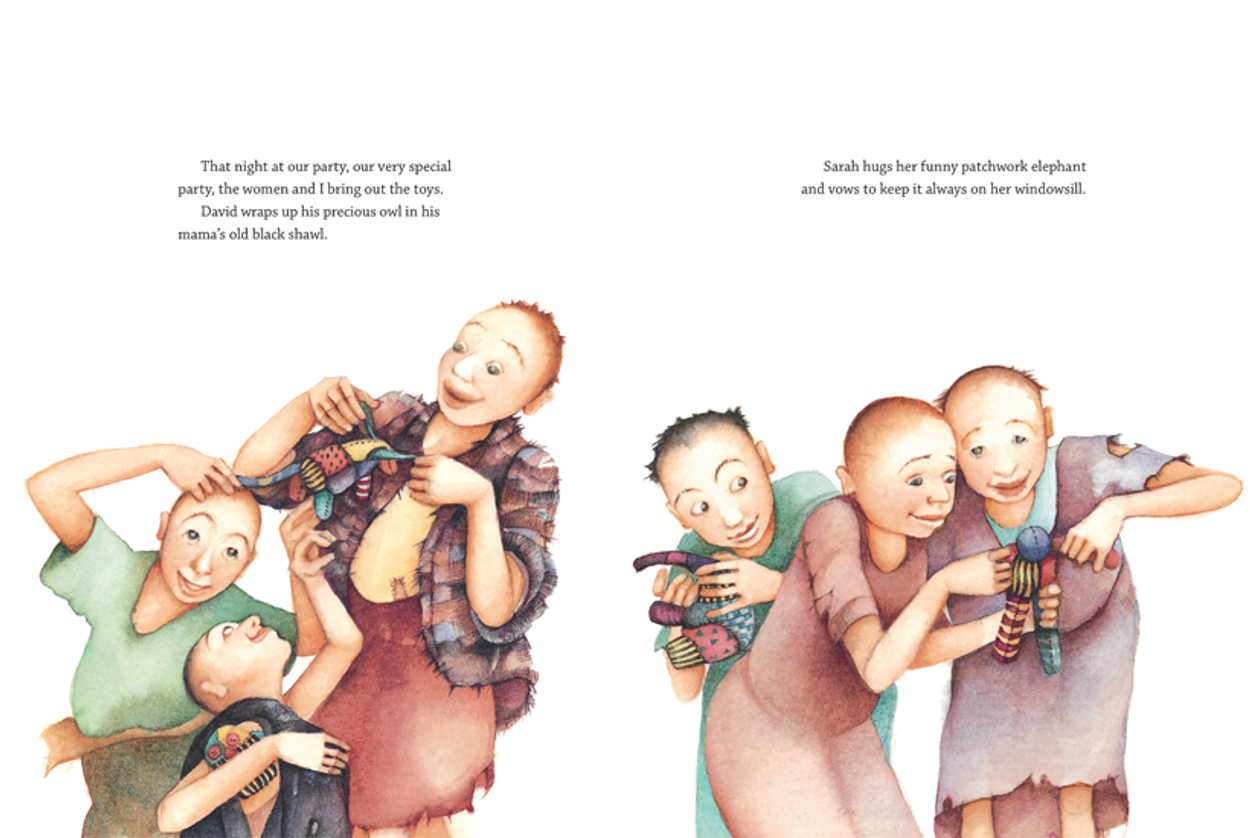

For a story set in a concentration camp, the opening sentence is incongruous: “We are planning a party, a very special party, the women and I.” The narrator is a girl of about 10, Miriam, who lives in hut 18 with a group of older women, a younger girl named Sarah, and a 4-year-old named David. Unlike Sarah and David, Miriam is old enough to remember a time before the war, when she had a mother and a father and her “very own bedroom” with her “very own toys.” Here, in this unnamed place of horror, there are none of those things, only a longing for what once was. But the people in Miriam’s hut are resourceful and hopeful; emboldened by rumors of impending liberation, they are making toys for the children with whatever scraps of fabric and thread they can find. The story is fictional but inspired by true events: Wild includes two quotations as a foreword and afterword, one describing the stuffed toys made by women in Belsen for the first children’s party after the liberation, the other from a first-hand account of the liberation of Bergen-Belsen by Dr. Hadassah Rosensaft.

Miriam narrates the story in simple, unsentimental language, at times reminiscent of a 1950s primer. Describing David, she says: “See him there in the corner with his mama’s old black shawl. See his hungry eyes and legs.” Later, when the camp is finally liberated: “Everyone, everyone, the soldiers are here! See their guns and their tanks and the big gates swinging open!” For adult readers, this phrasing is incongruous. Instead of Dick and Jane, we see the mechanisms of oppression and war from a child’s point of view, told in a child’s voice. If we’re disturbed by the simplicity and naivety of the language, it’s because we’re supposed to be. For younger readers, especially those unfamiliar with the Holocaust, the text reads differently: Miriam is simply a peer describing her experiences in a straightforward way with minimal historical context, as any child would.

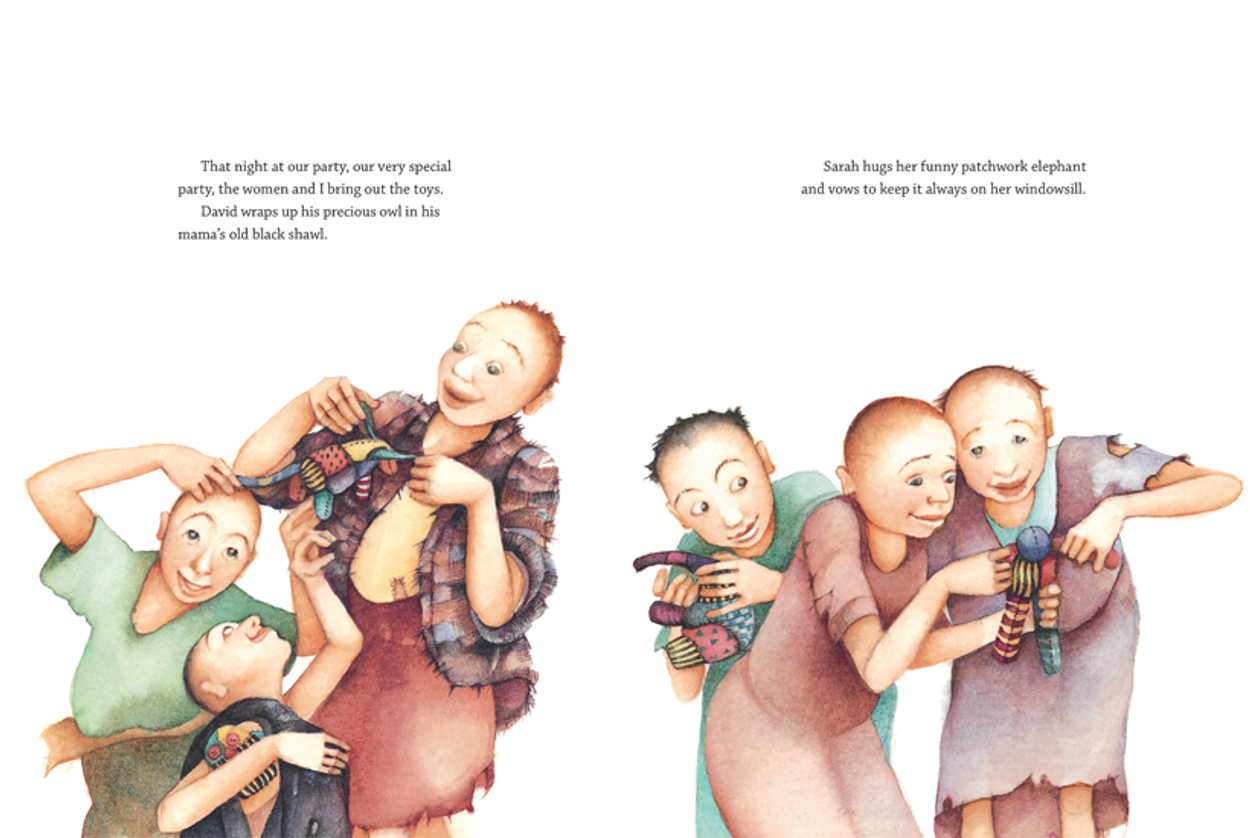

Like the text, Vivas’ illustrations—rendered in a muted, pastel palette—juxtapose the horrors of the camps with a more naive, childlike, storybook world. The women and children have skinny legs and shaved, almost bulbous, heads. Their clothes (not uniforms) are threadbare and torn. But Vivas draws them in a way that restores their dignity: Their watercolor eyes are wide and expressive, alternately fearful and mirthful; their meager figures fill the large pages. Their proportions, and the fact that we do not actually see the liberators, reinforce the message that the prisoners are the heroes of the story, not its victims.

These narrative and illustrative choices are incredibly moving, but not without their weaknesses. When the book was first published, some reviewers expressed disappointment at how the topic was handled, concerned that the themes and imagery were inappropriate for young readers. The Publishers Weekly review took umbrage at its “improbable plot” and “grotesque figures,” concluding that there was “something monstrous about forcing the moribund into cheerful attitudes.” Most reviews were positive, however, and the book was short-listed by the Children’s Book Council of Australia for Picture Book of the Year in 1992.

Michelle Prawer, who taught English at Jewish schools in Melbourne (including the one I attended) for many years, and is now a Ph.D. student in literary studies, recently wrote to me in an email that she found the illustrations alarming when she first read the book: “They are stylized depictions of survivors, distorted for effect, but they are quite haunting.” At the time of publication, she explained, there would not have been “many attempts to depict the Holocaust in a picture book for such young readers, and this in itself would have been confronting.”

The promise of “celebration” is certainly an unorthodox entry point to a story about the Holocaust. Miriam’s focus (and thus, the reader’s) is on life and imagination and the comfort of memory. The final message is a hopeful one. The arrival of the soldiers represents the restoration of order and justice, chicken soup is abundant, the children receive their toys, the human spirit reigns triumphant. This is entirely appropriate for young children—why should a 9-year-old expect anything else from the world? And yet, Let the Celebrations Begin is a fantasy of survival, one which elides the truth of Holocaust, in which 1.5 million children died, and very few as young as Miriam and David survived the camps. Should Wild or the publishers have included more historical facts within the text of the story? Or does that responsibility fall to us, the adults who will read and teach this book to children?

Though the critic in me is cognizant of the book’s limitations, the reader in me loves it and finds solace in it. I cannot read Let the Celebrations Begin without tearing up, especially when we are told that the liberators stare at the inmates “oh, so strangely, making soft noises in their throats.” Their horror is inarticulate. In that moment, multiple perspectives are masterfully layered: We are close to Miriam’s point-of-view and her jubilation, but we also gaze upon the characters as the liberators would have, their cachectic faces peering out from the page. This poignancy is heightened by our own knowledge of the incomprehensible scale of the Holocaust, of which neither Miriam nor her liberators are yet aware. The effect is haunting.

For me and I think other Australian Jews of my generation, Let the Celebrations Begin is more than just a book about the Holocaust. It’s a portal into a dark, mostly inaccessible world that once contained our grandparents, and many more family members who did not survive. This perhaps speaks more to the bubble of my community and the myopia of childhood, but I remember being truly shocked to learn that there was a country with millions of Jews—America!—and most of them had no direct connection to the camps. Almost all of my peers in Melbourne had grandparents who were survivors, and this simple fact explained the quirks, or neuroses, of our loving but overprotective families. (One of my friends once wryly commented that some sort of collective Holocaust memory dust must have been added to our milk in preschool, like a supplement.) I have no memory of learning about the Holocaust for the first time—I simply always knew that millions had died in horrific circumstances, that my grandparents were lucky to have survived, and that my existence, therefore, was a small but miraculous accident of history.

Reading Let the Celebrations Begin, I think, was how I first began to empathize with my grandparents’ experiences. Up until that point I had imagined all the survivors I knew enduring the war in their elderly bodies, speaking heavily accented English peppered with Yiddish and the occasional, surprising Aussie idiom. Now I realized that like me, they, too, were once young, and native to a different world. Color started to creep into a narrative that I had always imagined in grayscale, mirroring the scene in which Miriam recalls her home and her toys—the only spread rendered by Vivas in the vibrant primary hues of childhood. I could suddenly imagine myself in that inarticulate world or at least imagine them as young people in that world. In one of the most poignant scenes, Miriam recalls the simple act of eating chicken:

It is years since I chewed on a chicken leg. Back then, I didn’t like the skin or fat. Now I would gobble it all up—skin, fat and bones. I would lick the plate and pull the wishbone and make sure David had second helpings, third helpings, fourth helpings of everything!

This is exactly how I learned to eat chicken: skin, flesh, marrow, and all. At the end of each Shabbos meal my father would gather the bones from our plates and systematically bite them open vertically, down the center, sucking out the marrow, till all that remained on his plate was a graveyard of bone fragments. It’s not the most genteel way to eat chicken, but it’s certainly the most gratifying, and the least wasteful. Like a magic pen, Miriam’s hunger and wistfulness highlighted for me the invisible connections between my present and my family’s past. I suppose I didn’t need the fact of death spelled out for me explicitly in the story; it was always amorphously present.

Of course, this isn’t so for all readers, and criticisms of the book tend to focus on its vagueness and lack of historicity, and also on the question of whether it is even appropriate for children. The text contains no mention of the terms “Nazi,” “Holocaust,” “concentration camp,” or even “Jews” although the title page shows a hand-sewn Star of David, and a larger spread shows barracks surrounded by barbed wire. The Publishers Weekly review recommended the book for children aged 4-7, which wrongly conflates the format with its intended audience. “The book is not meant for 4-year-olds,” Wild cautions in an author’s note in the new edition, “yet because it is in picture book format, some people automatically think it can be read to little kids.” Prawer echoed this sentiment, recommending the book for “a secondary classroom [seventh grade up] rather than a primary one,” citing the emergence of picture books as a genre for older readers. Based on my own experience, I’d recommend Let the Celebrations Begin for older children—say, 8 and up—as long as an adult or teacher is available initially to provide context.

“These days I don’t think the book is regarded as so radical,” Wild wrote to me this week in an email, highlighting the popularity of novels such John Boyne’s The Boy in the Striped Pajamas and Morris Gleitzman’s Once series, which have accustomed readers and reviewers to Holocaust stories for children set in concentration camps. Kids are always more emotionally resilient, and book-curious, than we realize. (How many of us read Maus before we were teens?) We may want to protect young children, especially Jewish children, from the trauma of the Holocaust, but we shouldn’t underestimate their ability to grasp basic concepts of war, persecution, and genocide—after all, the world looks pretty grim right now. The challenge lies in in striking the right balance between objective historical facts and age-appropriate storytelling.

The problem is, we can’t have it both ways: A book cannot frankly convey all the facts of the Holocaust (or any violent historical event) and be suitable for all young readers at the same time. Maturity and literacy levels vary. There’s no such thing as the perfect Holocaust book for children, just as no novel can fully convey the experience for adults. The only way to subvert this dilemma would be to restrict our reading to nonfiction and memoir, but those genres have their own limitations. Fiction is one of the best ways to cultivate empathy and curiosity in children. If the point is to gently assimilate knowledge of the Holocaust into a child’s consciousness with emotional honesty and hope for humanity, Let the Celebrations Begin is a compelling place to start.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Elissa Goldstein is Tablet’s director of audience development. She also produces Unorthodox. Follow her on Twitter here.

Elissa Goldstein is Tablet’s director of audience development. She also produces Unorthodox. Follow her on Twitter here.