Little Shop on the Prairie

A century ago, Jewish immigrants in western Canada found a niche operating general stores in rural towns. My grandfather was one of them.

In the mass migration of Russian and Eastern European Jews to North America from the early 1880s to the 1930s, Canada was a clear second choice to the United States as a final destination. Among the more than 2 million Jewish immigrants who made the journey from 1882 to 1914, for example, less than 6%, or approximately 110,000, arrived in Canada.

As in the U.S., where the vast majority of these newcomers settled in cities such as New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago, in Canada, they mainly opted for urban centers like Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg. At least initially, most of these immigrants lived in crowded and impoverished neighborhoods and eked out livings as peddlers, shopkeepers, and garment workers.

A small minority ventured into the Canadian countryside where, owing to the financial aid provided by the Jewish Colonization Association, they established Jewish agricultural colonies, mainly in Saskatchewan. Nearly all of them either failed or were abandoned by the early 1930s. Other Jewish immigrants found more success in western Canada, however, by owning and operating general stores in rural prairie towns. One of these immigrants was my maternal grandfather, Sam Kliman.

Shaul (“Shailek”) Klejman was born in 1902 in Mezerich (also Mezhirichi or Międzyrzecz), 186 miles west of Kyiv, a Ukrainian—and at various times Russian and Polish—town celebrated as the home of great rabbis and scholars. He was 19 when he arrived in Canada in 1921, accompanied by two of his sisters, Hinda and Rae (or Ruchel). Almost immediately the family’s surname was changed to Kliman, and Shaul became Sam. Within a few years, his other two siblings, Sima and Meyer, joined them. The Klimans and their respective spouses all ended up in Manitoba and in one way or another, almost the entire extended family was involved in the general store business in a half-dozen different towns.

The decision by Sam and his family and many others to pursue careers as rural general merchants was not entirely by chance. Certainly the peddling and mercantile experiences of the first Jewish immigrants to Manitoba—linked to the petty trade done by generations of Russian and Eastern European in the old country—paved the way, but other factors played key roles as well. Jewish Winnipeg grocery and dry goods wholesale companies, in addition to several friendly non-Jewish companies, were prepared to provide the rural merchants with goods on credit. Plus, there was startup capital available from open-minded bankers and successful Jewish store merchants who had been in the business for a while. These budding entrepreneurs were interested in making smart investments in a network of country stores and also desired to help out the newcomers. In any event, it has been estimated that by the late 1920s, there were about 118 Jewish merchants scattered throughout Manitoba—the Kliman family among them. Likewise, in rural Ontario, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia, hundreds of Jews operated general stores. The impact these various merchants and their families on the individual communities in which they resided was substantial.

In the case of Sam, his brother Meyer, who established a general store in the town of McCreary (155 miles northwest of Winnipeg) and several other family members, the required financing began with the Rabkin brothers of Portage la Prairie, a town 53 miles west of Winnipeg. Max and Jacob Rabkin had come to Canada in 1908 as young men. For a brief period they had worked in northern Ontario as laborers, cutting trees and hauling wood. They eventually moved to Portage la Prairie, opened a general store, and prospered.

During the 1920s, one of the young men the Rabkins hired to work for them was Max Kirshner, Sam’s cousin. Both Max and Sam desperately wanted to be self-employed, something the Rabkin brothers could understand. At the time, purchasing and setting up a general store cost approximately $10,000. As newcomers, Kirshner and Kliman hardly had such available capital or the credit rating to obtain the money from a bank. Instead, they made a deal with the Rabkins, who in 1925 provided the two men with sufficient funds to open a general store in the town of McGregor, 76 miles west of Winnipeg.

The partnership in McGregor between Kirshner and Kliman lasted about a year. Sam sold his share in 1926 to Kirshner and the Rabkins for $4,000—a substantial fortune for a 24-year-old Jewish immigrant. By this time, he was dating 18-year-old Sarah Rosen from Portage la Prairie. Sam and Sarah were married two years later.

For a brief time in 1927 or so, Sam owned a general store in a village close to McGregor. Yet he could not make a go of it because of the small population and the antisemitism he encountered. He sold this store, absorbing a loss of $1,000, but soon found another general store in the town of Holland, about 90 miles southwest of Winnipeg. The Rabkin brothers agreed to become his partners in this venture in 1928. It would take him 10 years before he was able to buy them out.

Sam and Sarah were the only Jewish family in the town for most of the three decades they lived in Holland. This was the experience of nearly every other Jewish family that owned a rural general store in Canada. With their four children—Freda, Bernice (my mother), Melvin, and Sharon—the Klimans lived in a large house, a short walk from the store. While Holland had electricity by 1935, it did not have a public water or sewer system until the early 1960s. It was possible to install indoor plumbing, connected to private wells and septic systems, but Sam, who watched his money, resisted doing so because he and Sarah were always planning to move into Winnipeg. Consequently, the family endured a backyard privy and hot water heated on the stove for weekly baths in a large tub placed in the middle of the kitchen. In 1951, the Klimans finally purchased a house owned by a cousin in Winnipeg’s North End. Freda, the eldest, who was soon married moved into the city first and Sarah and the other children gradually relocated there as well. Sam continued to run the Holland store and commuted the 90 miles back and forth (other than in the summer) until his death in 1958 from a heart attack at the age of 56. Sarah died in 1995.

The Klimans found the economic and social climate in Holland welcoming. By the mid-1920s, southwest Manitoba had a diverse rural population: Mennonites, Belgians, Dutch, Ukrainians, and Poles, as well as English and Scottish, with First Nations reservations here and there. For a Russian or Polish Jew, dealing with this multicultural mix and learning bits of several languages—including Cree and Ojibwe—was natural and became a part of doing business in the country. The storekeeper became, as Louis Rosenberg, a JCA official, commented, “the adviser, letter writer, translator, and friend. No merchant with a command of only one language and lacking practical experiences of the psychology of the various groups could have met the requirements of this pioneer period. The Jewish country general storekeeper extended credit to the farmer until the crop was harvested. He sold everything from cornflakes and canned salmon to overalls, fur coats, and harnesses, and knew the names of each article in several languages.”

The members of the Kliman family integrated themselves into the life of Holland. My mother and her siblings (other than Sharon, who was 2 when Sarah and the children moved to Winnipeg) attended the public school; they joined clubs, participated in community events, and even donated money to the local church. In 1967, the Holland History Book Committee, which assembled a town history, noted that Sam Kliman “was a kind and good-hearted man, always willing to listen to anyone’s hardships and offer help if possible. He was a friend to everyone.”

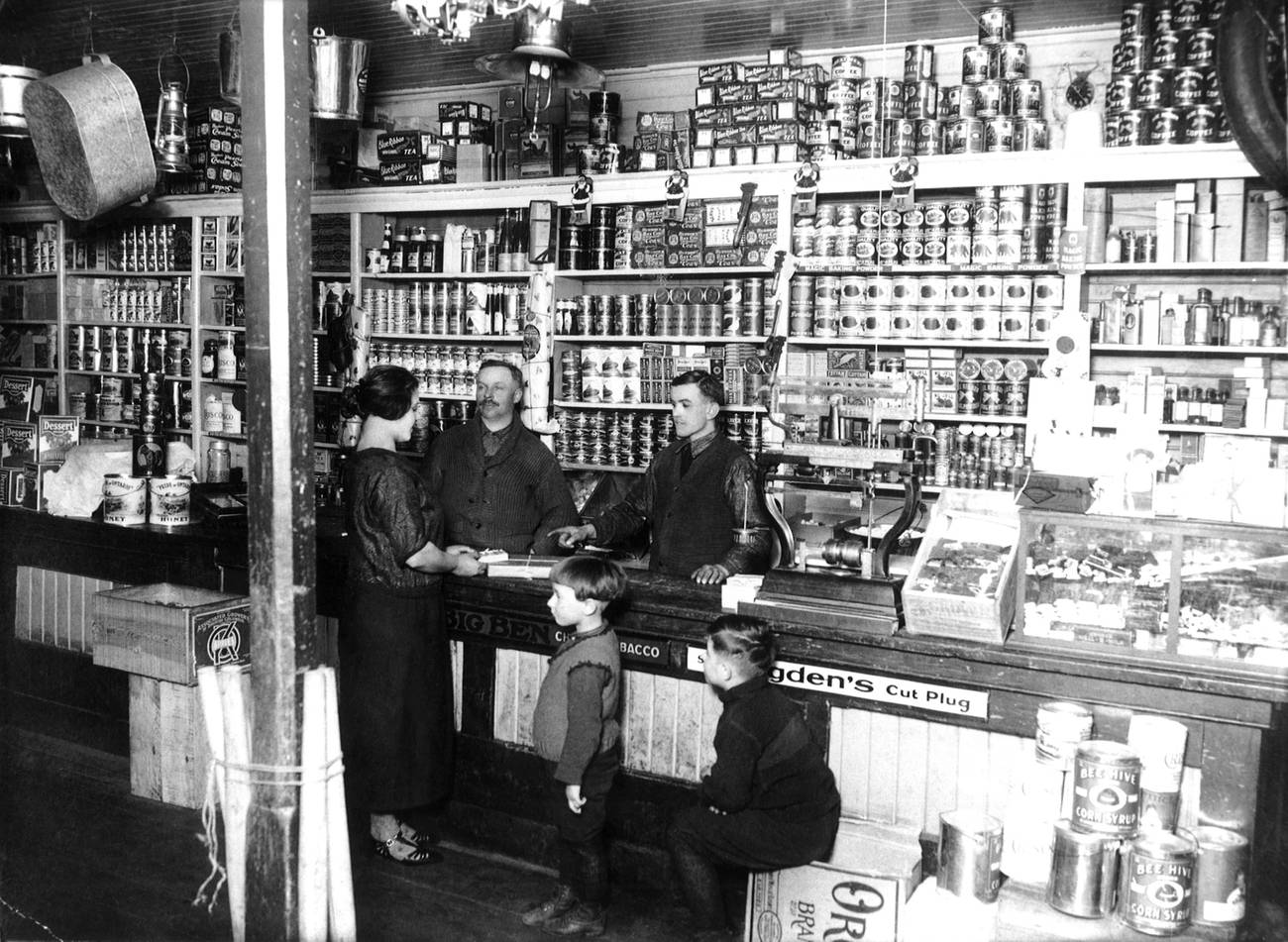

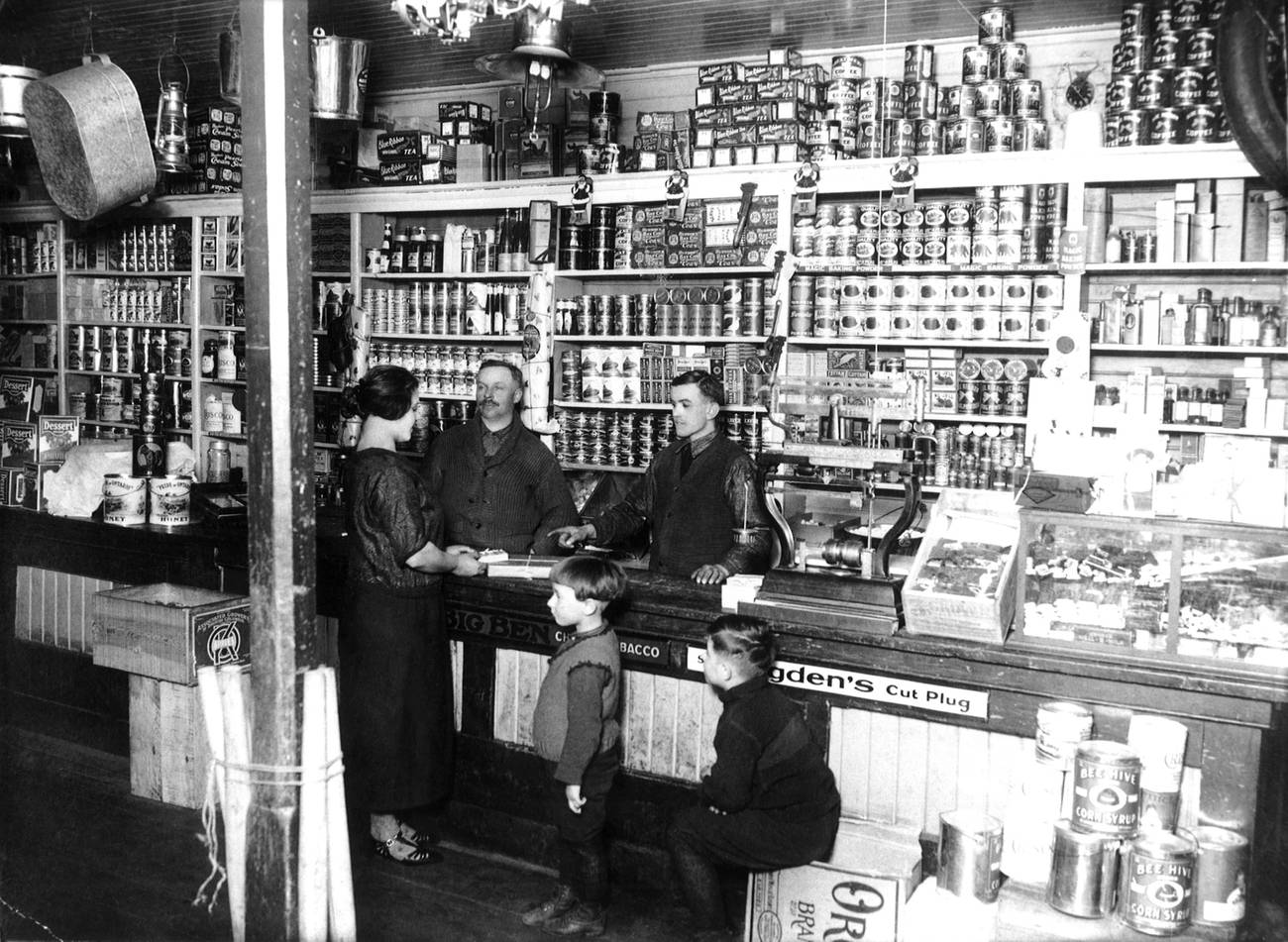

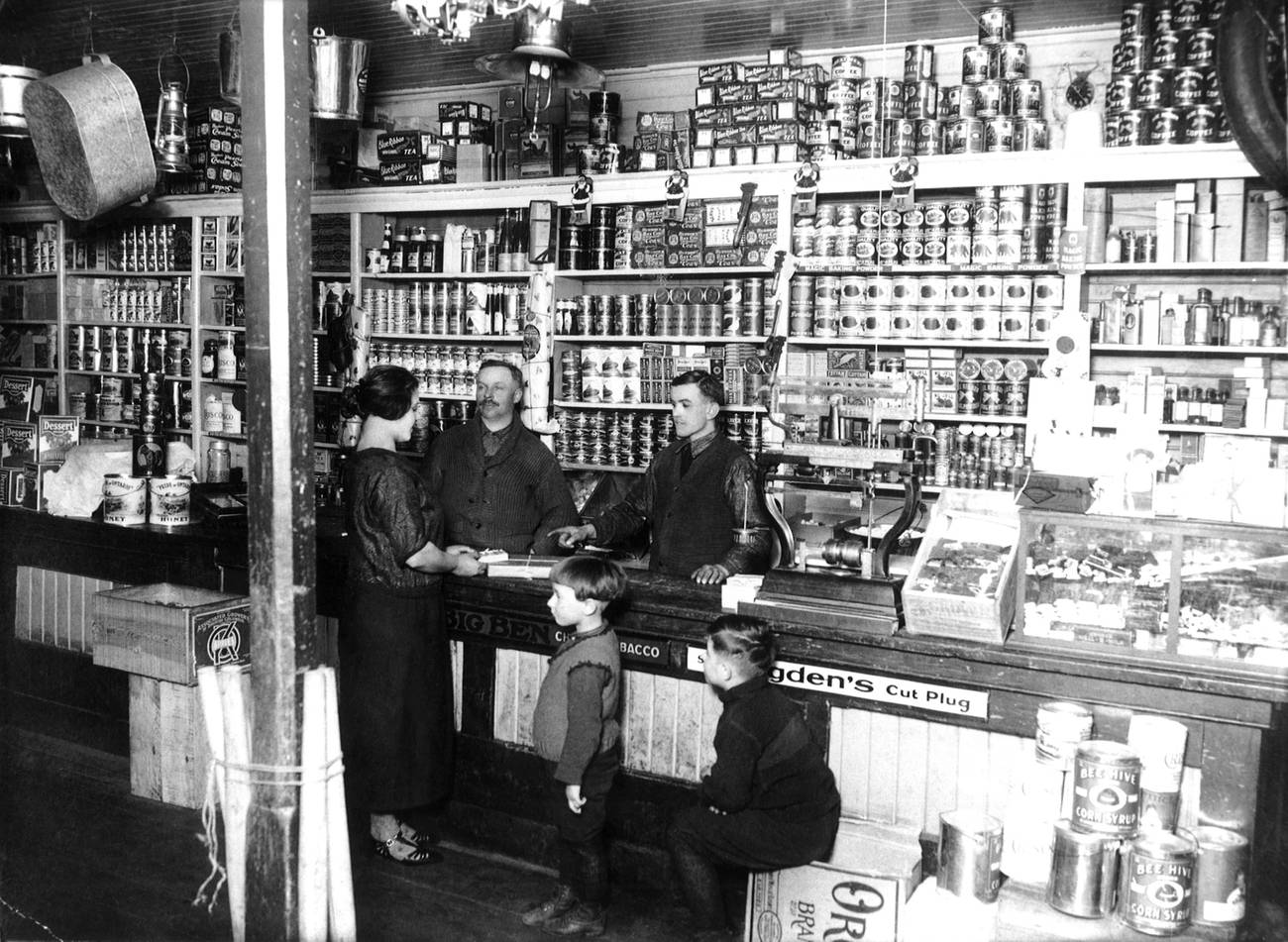

Kliman’s general store, like every other store across rural Manitoba, was a virtual Turkish bazaar of groceries, spices, clothing, boots, shoes, pots, pans, and knickknacks of every type. The store was open six days a week, from early morning until early evening, and on Saturday evening during the summer until midnight. Stocks were replenished by traveling Jewish peddlers, train and truck shipments from Winnipeg, and with goods brought in from partners like the Rabkin brothers. Local farmers regularly bartered live chickens for cash and/or groceries—those used by the merchants’ families were kept apart from others, and sent to the shochet (ritual slaughterer) in Winnipeg to be killed. In Holland, Hutterite farmers from a nearby colony brought fresh honey packaged in one- and two-pound tin tubs to the Kliman store. First Nations traded fur skins and Seneca root.

Sam, his brother, and their relatives, like all Jewish storekeepers on the prairies, worked hard and put in long hours. Most of them made a decent living; owning a store always put food on the table, especially during the Depression. But the entire business revolved around an elaborate and problematic credit system based on an unpredictable agricultural economy. The storekeepers obtained their goods on credit from Winnipeg wholesalers. The merchants, in turn, sold their groceries and supplies to farmers, who often could not settle their bills until the fall harvest—and sometimes not even then. Invoices stacked up and cash flow became a real problem. No one liked the system, yet that was the price of doing business in the country. Local banks frequently came to the rescue, but they had tough policies. Often, farmers ran up huge debts at the store. Most were eventually settled, yet some were not and had to be written off.

For the lone Jews in a town or village, maintaining a Jewish identity and adhering to religious precepts was a challenge. Sarah routinely sent chickens into Winnipeg where they were koshered. On the High Holidays, the families would journey to Brandon, Portage la Prairie, or Winnipeg for prayer services. Passover also entailed extended visits from relatives from other towns for large Seder gatherings.

Jewish parents living in the country shared one great fear—that their children would not marry within the faith. Friendships and social and sports activities with non-Jews were acceptable, but actual dating was out of the question. Eventually, most rural Jewish parents sent their children into Winnipeg or another larger prairie city to further their education and meet a Jewish spouse.

The worst time of the year for Jewish youngsters, by far, was Christmas—“the season of bitterness,” in the words of Fredelle Bruser Maynard, whose father operated a string of general stores in towns in Saskatchewan and Manitoba during the 1920s and ’30s. “Lights beckoned and tinsel shone, store windows glowed with mysterious promise,” she wrote, “but I knew the brilliance was not for me.” Her father, like every other Jewish father, tried to placate her with Hanukkah. But somehow the holiday celebrating the Maccabees’ courage and resistance did not have the same pizzazz. Not being allowed to share fully in the town’s festivities, to receive a present from Santa Claus at the town Christmas concert was a bitter pill to swallow. It reinforced every Jewish child’s feelings of separateness, difference, and isolation.

One Christmas, a teacher at the Holland Public School decided that my mother, her only Jewish student, should play the Virgin Mary in the class’s holiday pageant. She was ecstatic, her mother, Sarah, was not and Sarah put her foot down. No matter how much Bernice cried and pleaded, her mother refused to give her consent. “Another little gentile girl got the part instead,” as my grandmother later told the story.

In the years following WWII, the majority of Jewish families gradually purchased houses in Winnipeg or other cities, sold their rural businesses and properties, and left their country lives for good. Most Jewish children had no desire to stay or take over the family store. Many had plans to attend university and become professionals. But a few did become storekeepers, and had no regrets about doing so.

A year after Sam’s death, Sarah sold the store in Holland to a local resident who modernized it and turned it into a Lucky Dollar Store. Sam’s brother Meyer’s family in McCreary held on to their general store for more than a decade after Meyer died in 1950. His son Hy and his wife, Lovee, ran it for about a year. Then, in 1953, Hy’s younger brother Lou, who was pursuing a career in show business in New York City and had married Estelle Kravitz from Brooklyn, decided to return to the town and take over the store—much to the chagrin of Estelle’s parents, who could not understand why their daughter wanted to live in the backwoods of Manitoba. Nonetheless, Lou and Estelle ended up staying until 1962 and raising their family there.

There were a few other Jewish families scattered across the prairies who kept operating their general stores into the early to mid-1960s. Yet, a strong desire to raise their children in a more Jewish environment where they could attend synagogue, find a Jewish spouse, and send their own children to Jewish schools made moving into urban centers both desirable and inevitable.

Partly adapted from Coming of Age: A History of the Jewish People of Manitoba.

Historian and writer Allan Levine’s most recent book is Details Are Unprintable: Wayne Lonergan and the Sensational Café Society Murder.