The Lower East Side Madam

‘Mother’ Rosie Hertz ran a network of brothels in the early 1900s and spent years paying off corrupt cops—until she finally ended up behind bars

“Mother” Rosie Hertz could have been mistaken for just another Yiddishe mama of the Lower East Side—albeit one who favored expensive jewelry, fancy lace, and fine furs. In 1912, she was in her mid-50s. At 5-foot-4, she was short, but not yet rounded like other women of her age. She preferred wearing a big white apron over her dress and like any doting Jewish mother she often pinched the cheek of any young woman or man she was speaking with. She always had pennies for the eager children who roamed the streets of the congested East Side.

Behind this façade, however, was a sharp and cunning businesswoman, who for close to three decades was the most notorious madam in New York City. Judge Joseph E. Corrigan described her in 1912 as a “kind of godmother for the prostitutes of the East Side, whose shop for disorderly women was as much a public feature of the Lower East Side district as the Brooklyn Bridge.”

Along with her husband, Jacob, or Jake, who, at 65 years old in 1912, was short and bald with a moustache; her two brothers, Dave and Max Rosenbach; a couple of cousins; and other clerks, procurers, and watchmen, she oversaw at the height of her notoriety, from the late 1880s to 1913 or so, at least nine brothels—disorderly houses or “resorts,” in the parlance of the day. They were all located in or near the Lower East Side; in 1913, it was reported that there were approximately 420 brothels in the neighborhood. Hertz employed dozens of mostly Jewish prostitutes in a criminal enterprise that had by 1912 made her and Jake close to $1 million (about $30 million today). “It is better to stay away from Allen, Chrystie, and Forsythe streets,” the Yiddish newspaper the Forverts (Forward) advised its readers in 1898. “There is an official flesh trade in the Jewish quarter. In the windows you can see human flesh instead of shoes.”

As the undisputed “Queen of the Harlots,” and one of the chief sellers in this “flesh trade,” Rosie held court from her home on Keap Street in Brooklyn, which she and Jake owned. In February 1913, The New York Times described her operation like this: “Every Saturday afternoon Mrs. Hertz would dress herself in the brightest colors of silk and laces, place jewels upon her head and around her neck, fill her fingers with diamonds, and then sit in a large chair placed on dais in the parlor of her Keap Street home. At a certain hour the eight women who managed the disorderly resorts for her would call and remain huddled in a little ante room until she gave the word, and then they would go before her one at a time. They would have to partly prostrate themselves when they reached the dais and hand to her their books, and all the money they had taken in enclosed in chamois skin bags. Mrs. Hertz would count the money, go over the accounts, and administer words of praise or blame as the occasion seem to warrant. Business over, tea would be served, and while the social function was going on Mrs. Hertz would give little lectures about how to succeed in business and by what trials of strength and endurance she had built up her business.”

The story Rosie related to her “management team” began with her immigration to New York City from Hungary in 1882 when she was almost 30 years old. She was most likely already married to Jake, who preceded her to the U.S. by several years. Her mother, Gittel Rosenbach, had also immigrated from Hungary by then. According to the resourceful Abe Shoenfeld—who in 1912 at the age of 21 was hired by Rabbi Judah Magnes, then the head of the recently established New York City Kehilla, the Jewish community’s central organization, to be the chief investigator of its Bureau of Social Morals with the aim of monitoring rising local Jewish crime, and prostitution in particular—Gittel Rosenbach may well have been the first Jewish madam in the city.

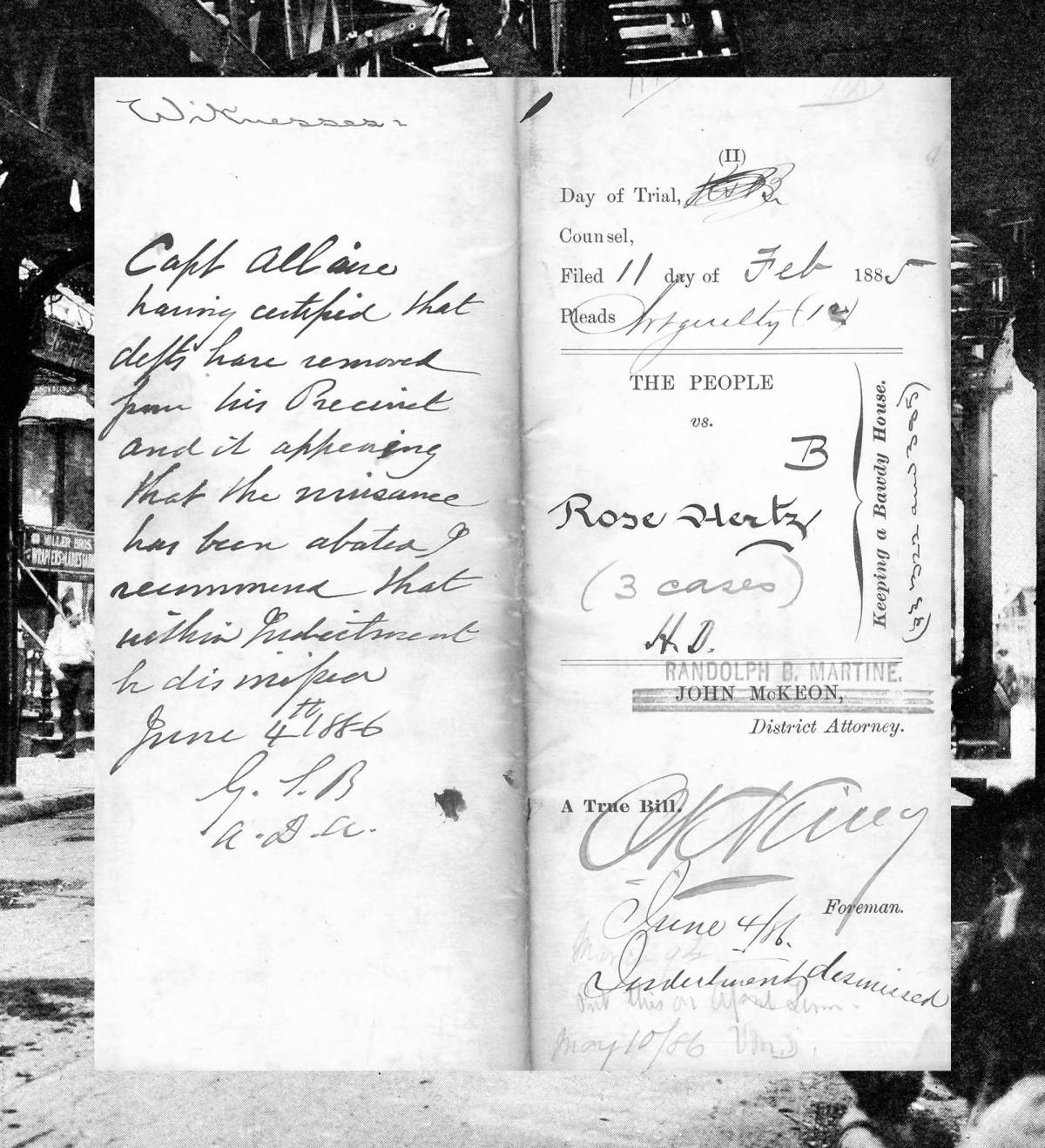

Rosie followed her mother into the family business and worked as a traveling prostitute, going “from one coal cellar to another—from one shoemaking basement to another and thus making money,” Shoenfeld recounted in a report. By 1885, she had opened her first brothel in a small apartment and faced her first of many arrests for “keeping a bawdy house.” But the charges, as with many that followed, for her, Jake, and other members of her family, were dismissed. And her business continued to expand.

Jake, too, attracted unwanted attention from the police, district attorney’s office, and civic reformers intent on ridding New York of this “social evil.” In October 1901, an official with the Committee of Fifteen, a New York citizens group that targeted prostitution and gambling—one of the committee’s major supporters was the Jewish financier and community leader Jacob Schiff—castigated Jake Hertz, as “the most notorious vender in this class of crime in the city … He is head of the ‘Red Light District Trust.’” (This probably refers to the Independent Benevolent Association, a burial and mutual aid society created in 1896 mistakenly suspected of being a Lower East Side “vice trust” of brothel owners, pimps, and everyone else involved in this enterprise.) Jake was said to be “pretentious and aspired to social standing, keeping carriages, a coachman and two liveried footmen.” He was arrested in late October 1901; the case vanished after an initial court hearing.

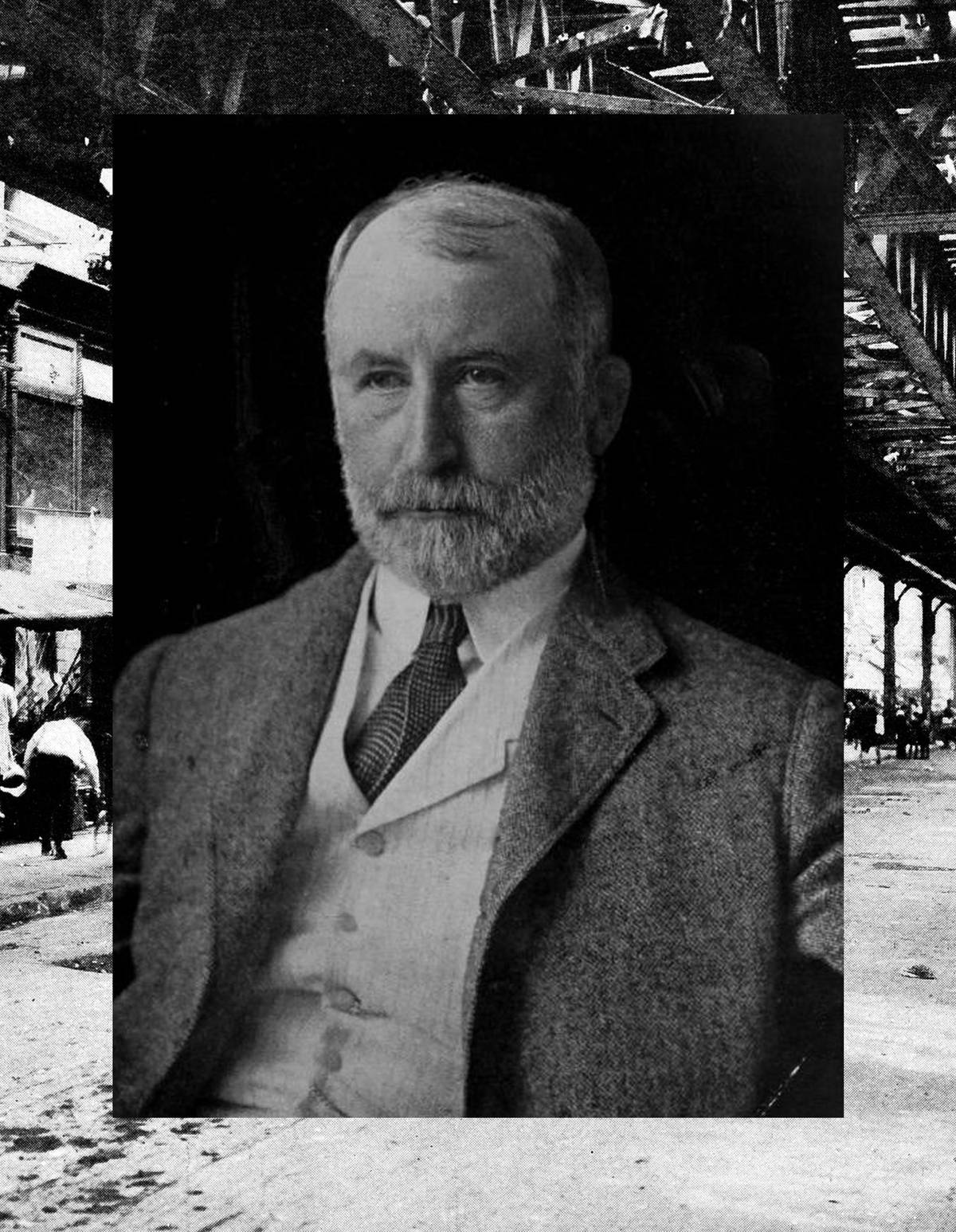

How did the Hertzes evade justice for so many years? Rosie befriended Democratic and Republican organizations and made generous donations to both annually. In 1904, William Gaynor, a friendly judge and liberal reformer when it came to constitutional legal rights (he was later the mayor of New York City from 1910 to 1913), granted a permanent injunction against the police standing in front of the Hertzes’ brothel at the Dry Dock Hotel at Bowery and Third Street and intimidating customers. This action outraged more conservative judges and magistrates, like Corrigan.

If the police were bothering Rosie and her various businesses, it was not because of the moral implications of what she was doing, but rather because they were not satisfied with the amount of the so-called “protection” fees she offered them. Rosie and nearly every other madam in New York benefited, legally at least, from widespread police and political corruption. Despite major investigations into the sordid inner workings of the police and the Tammany political (Democratic Party) machine in the 1890s and early 1900s—most notably by the Lexow Committee of 1894-95, led by New York state Sen. Clarence Lexow—the payoffs continued unabated. Over more than 20 years, Rosie had no choice but to regularly hand over thousands of dollars to police inspectors, captains, and patrolmen “on the take.” Often the funds were transferred via Tammany ward heelers, who worked for political bosses, who in turn were in cahoots with the police. It was simply the cost of doing business.

In 1913, the reform-minded Manhattan District Attorney Charles Whitman (who was elected as governor of New York in 1914 and served a four-year term) estimated that Rosie, at one point, was doling out as much as $2,400 a month (about $72,000 today) in graft. Thus, during this period, the police, “far from protecting the city from vice, were rather actively engaged in aiding and abetting the very conditions which they were obliged to protect,” Willoughby Cyrus Waterman pointed out in his 1932 study of prostitution in New York City. Nonetheless, it was a dangerous game. The police often reneged on assisting Rosie or one of her associates beat an arrest and a few nastier cops she dealt with over the years kept on upping their demands and became violent with her if she did not comply. She eventually paid them what they wanted.

Rosie was no saint or victim however—far from it. While many of the Jewish women she employed willingly chose to work as prostitutes and accept the reprobation of their families and community because it paid so much more than working in a sweatshop—$4 or $6 a week in a garment factory or doing piecework versus $12 to $15 (or more) a week “entertaining” male clients at a disorderly resort—some did not. (It should be added, as historian Edward Bristow notes, that in 1909 a Lower East Side physician “asserted that 80% of the prostitutes in New York suffered from venereal disease.”)

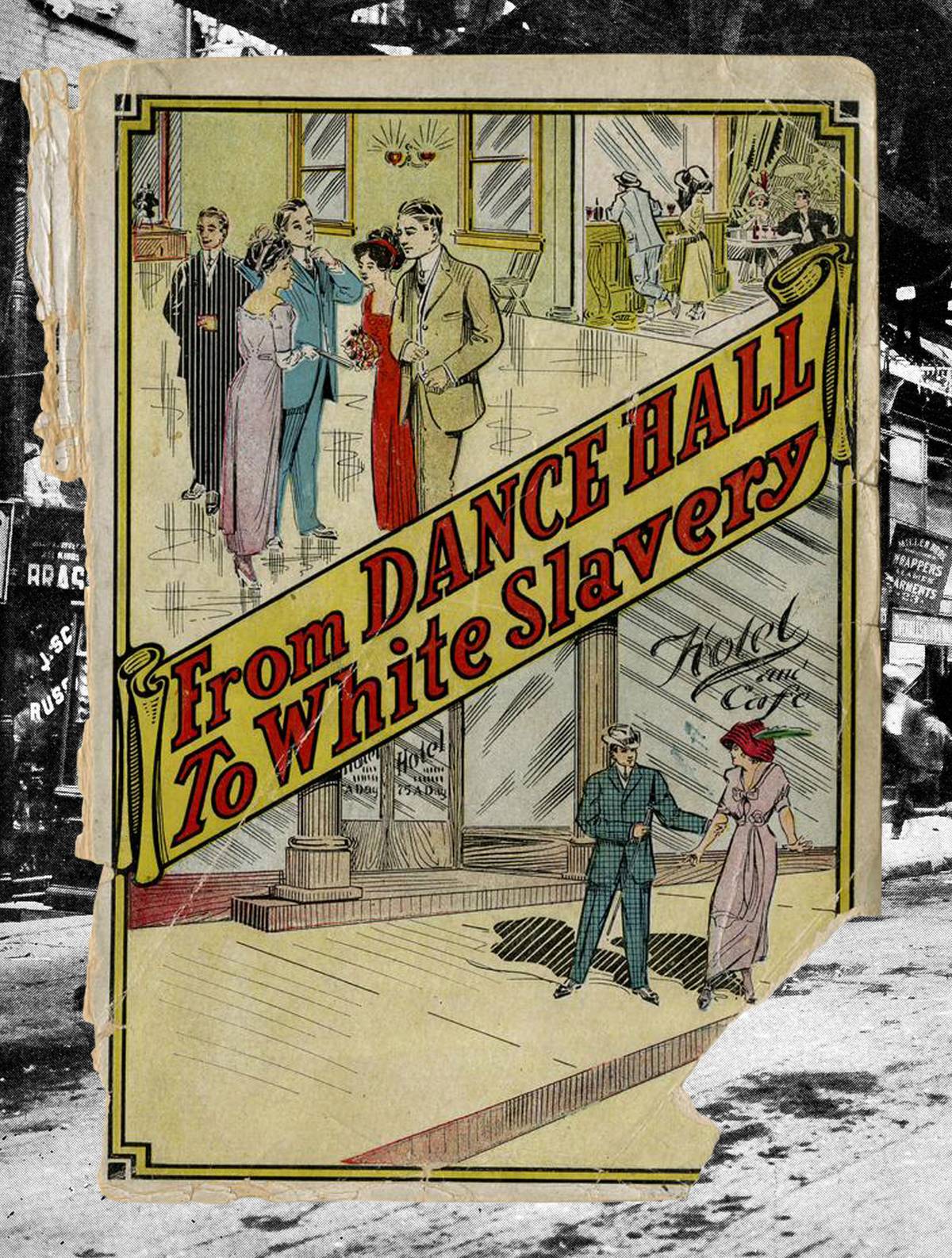

“White slavery,” which received much attention by politicians, social reformers, and the press in the first decade of the 20th century, may be now regarded as something of a moral panic, yet it did exist. And while Jews might not have been at the center of it, as the muckraking journalist George Kibbe Turner claimed in his sensational 1909 McClure’s Magazine article, “The Daughters of the Poor,” many Jews were indeed involved. Young Jewish women in Russia and Eastern Europe were conned by Jewish men into bogus marriages and brought to New York (or Buenos Aires and other locales), sweet-talked by Jewish cadets (pimps) on the lookout for single girls arriving at Ellis Island, seduced at dance halls by Jewish swindlers, and even kidnapped and then literally sold to an East Side brothel. It was brutal human trafficking that drove some of these young women to suicide by ingesting carbolic acid. And Rosie, whether she admitted it or not, sustained it, or at the very least, was willfully blind to the abuse happening in the commercial enterprise she cultivated for much of her life.

In one case, as Abe Shoenfeld reported, a young girl was ensnared by a pimp at an East Side dance hall. She was taken to one of Hertz’s brothels “where she was ruined and left as a prostitute.” Like other members of the Jewish community, Shoenfeld regarded Rosie and her family with disdain. “The operations of Jake and Rosie Hertz and family have been such that due to them firesides have crumbled—hearts have been broken—virginity has been polluted—virtue has been contaminated—and the very Eastside [sic] was leperously [sic] disgraced by the Hertz activities,” he wrote. “Rosie Hertz has been the teacher and mother of more prostitutes, whore madams, etc. than any other individual woman in the world. They would bring recruits to Rosie and she would show them the way. She would open up avenues of vice to the minds of innocent girls, and she would act motherly to these girls—and when I say motherly, I mean that she would relieve them of as much of their earnings as she could.”

Her luck ran out early in 1913. On Feb. 3, Rosie was convicted of operating a disorderly house at 218 East Ninth Street and incarcerated at the Tombs jail in Manhattan. A few weeks later, she received a one-year sentence to be served at the penitentiary on Blackwell’s Island (now Roosevelt Island). “Your name has long been notorious in connection with [prostitution],” stated Justice Cornelius Collins. “Only God knows the number of your victims.”

There was, however, a ray of hope for her. In the aftermath of the murder of Herman (“Beansie”) Rosenthal, a Jewish bookie and gambler, in mid-July 1912, DA Whitman wanted to get to the bottom of police corruption. (Rosenthal’s killing was allegedly ordered by New York Police Department Lieutenant Charles Becker, who was subsequently convicted and executed in July 1915. While Becker had been extorting brothel owners and illegal gambling operators like Rosenthal—who, tired of paying graft, had exposed Becker’s actions in an affidavit published in the New York newspaper The World and threatened to tell Whitman about it—questions have been raised about his guilt in the assassination plot.) Whitman offered a possible deal to Rosie, but first she had to confess to everything she knew about payoffs to the police. Her immediate response to this proposal was a definite “no.” She claimed she had been threatened at the Tombs and said she “would be cut into little bits before she would tell anything.”

It was later learned that following her arrest, she had paid Jacob Reich, alias Jack Sullivan, a Jewish fixer and bodyguard—who was initially implicated in the Rosenthal murder though later released by the authorities—more than $12,000 after he promised he could “deliver” an assistant district attorney who would see to it that the charges against her were dropped. She soon realized that neither Sullivan nor her so-called friends in the police department and the district attorney’s office were going to save her. On March 10, she met with Whitman for two hours and told him about paying graft to a long list of crooked cops and politicians for decades. When her meeting with Whitman ended and she was being led back to her cell at the Tombs, she began weeping and believed that her life was in danger because she had spoken to the DA. No one touched her and Whitman never came through with a deal to lessen her sentence. She lost her appeal in April and in early July she was transferred from the Tombs to Blackwell’s Island. “Woman White Slaver Goes to Jail,” The New York Times headline on July 6 declared.

Thereafter, Rosie Hertz more or less vanished from the public record. She presumably served most or all of the 12 months of her prison sentence. Then, she resumed her career as a madam. On Oct. 12, 1916, in one of the last newspaper articles to mention her, she appeared in women’s night court on a charge of running a disorderly house on Broadway and released on bail.

Jewish participation in prostitution in New York City, at least, began to wane by the early 1920s. According to Bristow, by 1924 only 11% of the women arraigned on sex-related crimes in New York City were Jewish. No doubt, there were Jewish madams still operating brothels in the Lower East Side into the 1930s, but Rosie Hertz, who would have been close to 80 years old if she was still alive by then, had likely retired before that.

Historian and writer Allan Levine’s most recent book is Details Are Unprintable: Wayne Lonergan and the Sensational Café Society Murder.