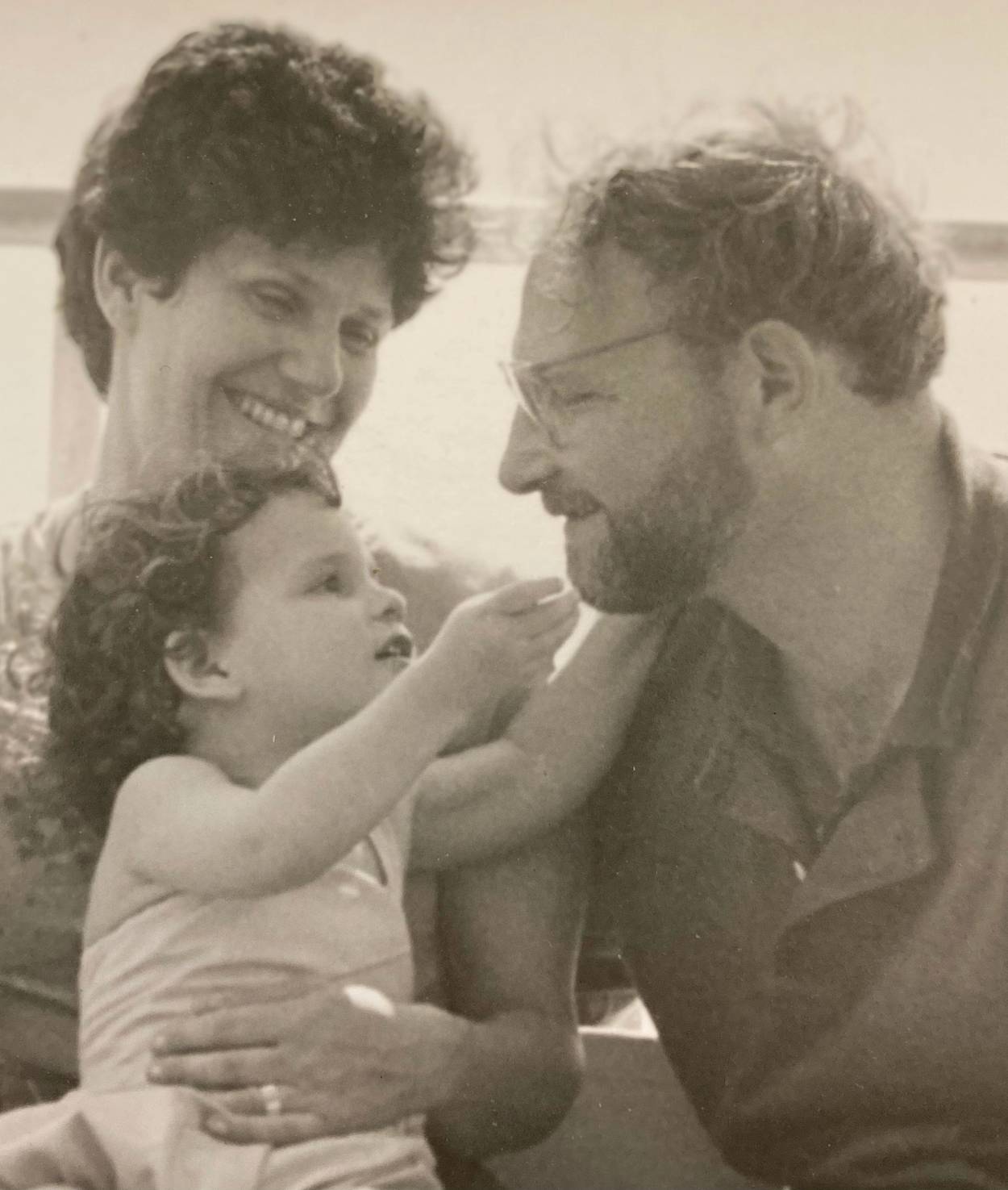

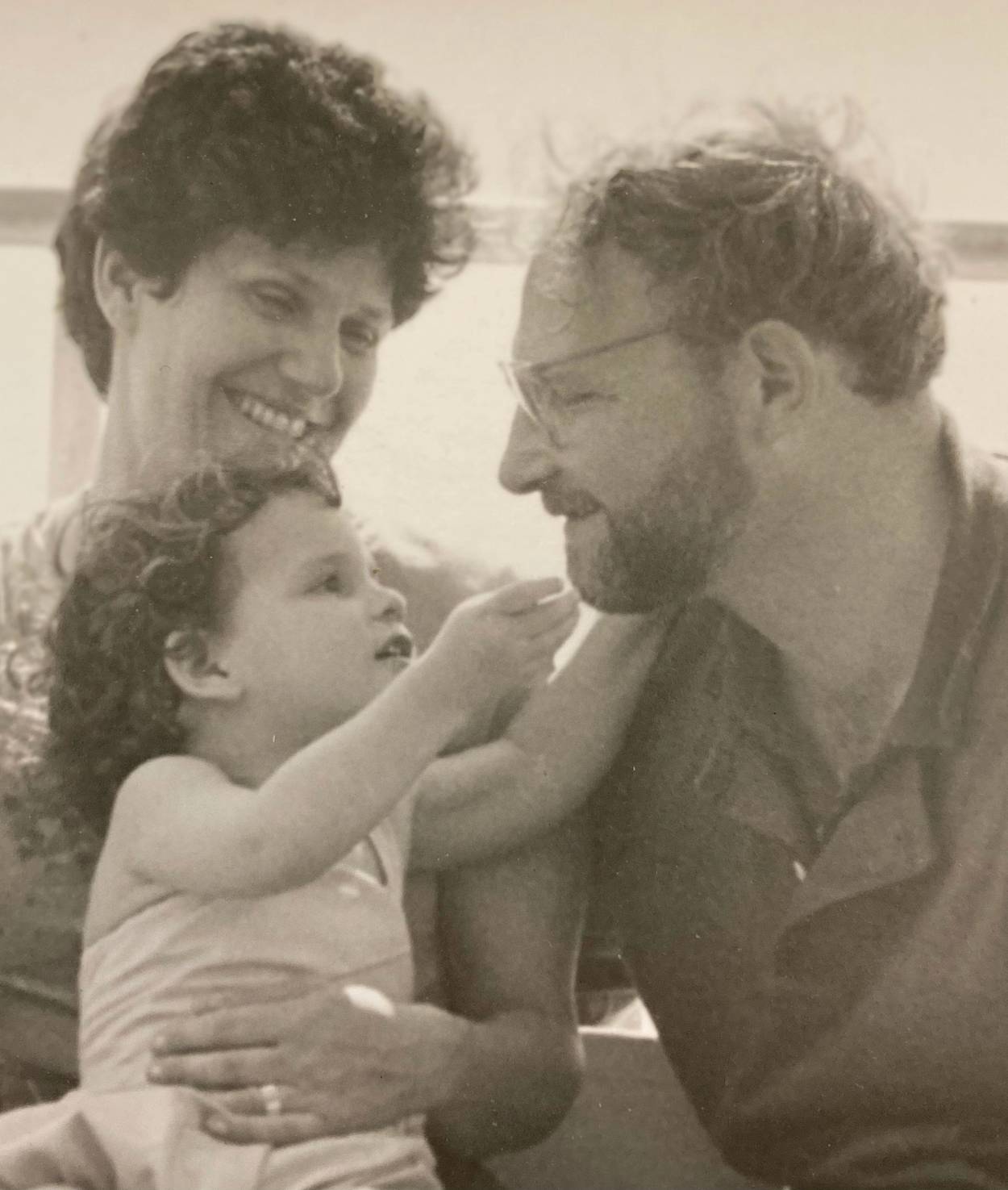

When the Cake Stops

Managing your relationships while mourning

Witnessing death transformed me, and when I emerged, relationships were fresh and complicated terrain. I was new, as if in all ways I was beginning my life again. Same life, new vantage point. Could my old friends understand this emergent woman I was becoming, marked by such a profound loss?

My relationships were about to change.

From the moment we buried my father, Jewish communal mourning rites and time sanctions were put into place.

The pre-communal time of aninut begins when a close family member dies and ends when they are buried in the earth. Aninut is a time for shock to be remedied, for death in its acuteness to be processed, with a sole task of working to bury the dead and to prepare all funerary rites. This is a period when one is considered to be in a suspended state, outside of normal functional activities. It is not yet time for full rituals of communal comfort.

Cultures around the world each have their own funerary practices and mourning rituals, often bound to prescribed time periods, and these ceremonial rites are almost universally communal. During an NYU talk on Black grief, I learned from radio host and political commentator Esther Armah of One-Week Ceremonies in Ghana, Nine-Nights celebrations in Caribbean cultures, and the Black Southern tradition of memory jugs, to name just a few.

Burial is ideally performed, in Jewish tradition (and remember, Jewish practice and law varies between all the iterations of Judaism out there), within twenty-four hours to one week after death and marks the beginning of mourning in community. Generally, barring festival times and other possible exceptions, the first seven days after burial are called shiva, a time when the mourners are cared for and nourished by their communities, receding as much as possible from their normal daily life. They are meant to sit lower than others, to cancel all work functions as much as they are able, and, ideally, their most basic needs will be met by the community in this time.

The burial also marks the beginning of aveilut, a period of mourning that dictates how long one might practice saying the Mourner’s Kaddish, a daily prayer for those in mourning. (Some believe this prayer is recited on behalf of the dead; others believe it is to raise the depleted spirits of those grieving; and still others might believe both, or neither, of these ideas. There are many iterations of Jewish practice and observance.) This period of being an avel, or mourner, lasts thirty days for the loss of a sibling, child, or spouse, and it continues for eleven months for the loss of a parent.

The first thirty days after burial are called shloshim. This period continues the staggered process of grieving—from shiva, the most intense phase, to the next, less intense (but still heightened) phase of mourning. During these thirty days, you return to functional daily life, but you are not yet a full member of joyful society. In strict Jewish sects, you don’t go to parties, weddings, or listen to music while mourning. You are still permitted by ancient code to dwell in the depths of despair during this time.

Separated out from collective time cycles otherwise marked on the calendar, these prescribed phases offered me personalized checkpoints for my process of mourning. I was grateful to have them.

In the Jewish tradition that I was raised in—a strict but not ultra-Orthodox iteration—mourners are told to remain at home for seven days after the burial of a close family member. People come to the mourners. They bring food. All kinds. My mother is a food writer; so in the days after we buried my father, chefs showed up with decadent challah bread pudding, Indian vegetarian food, Sephardic chicken soup, corned beef, Iraqi-style mujaddara, lox, bagels, Persian baklava, lasagna—everything.

I was a shut-in, and I was tended to, gathered around, cared for completely. Kaddish prayers were recited in our home in the evening. In fact, hundreds of people moved through our house over the course of a week, saying prayers, recalling great memories, and stuffing us with food. It was easy to make choices in those seven days, because they were made for me. No work. No travel. No nada. Supported exponentially, I sat with my grief, dropping deeply into it, a true privilege of time and space afforded me, during which I was able to remedy the symptoms I had of shock and trauma after seeing my dad die.

On the seventh day after his burial, ten people came to my parents’ house to do a ceremonial walk that marks the transition from shiva to the rest of shloshim. It was our first outing as mourners. It was December and very cold. I remember everyone who was there: three of my mother’s friends, my sister, my brother, my best friend and his mother, my sisters-in-law, and the rabbi who officiated the funeral. We did a walkabout in silence. Ten of us, dressed in black, around the DC neighborhood. It was solemn and, for me, scary: It was a coming out of sorts, a stepping out of this cocoon of care, a completion of the marked period of mourning.

I was panicked.

Do I go home?

Can I keep crying?

Can I fall apart?

Am I expected to resume my previous form?

What about my bed, can I still take to my bed?

Can I keep asking for help when I need it?

Is it weird that I feel completely confused?

What is this shame thing that has suddenly returned?

When is my sadness too much?

When, Freud, does mourning turn into melancholia?

Things moved so fast when shiva ended. My sister and her family flew home. My brother left soon after. A house filled with dozens and dozens of people was suddenly empty. Where there once were flowers and nurses and the enormous presence of my father at his soul’s fulcrum, there was now emptiness. The house felt void, dead, inverted, awful, and no one really wanted to come over.

I tried to fly back to New Orleans, thinking I was ready, two weeks after my father died.

I wasn’t ready.

I found my proof in flashbacks that knocked the wind out of me and brought me, crying, to my knees. When I did the laundry and the machine stopped, the way it just ceased to spin provoked a vivid flashback of my father’s breathing and heartbeat suddenly ceasing before my eyes. I slumped to the ground in my nook of a laundry room and just shook.

Want bananas in your cereal? No problem! But suddenly I’m in the kitchen remembering how my father used to leave his half-eaten bananas in the family fruit bowl, and then I’m cross-legged on the floor again, sobbing.

A few weeks after my father died, I returned again to DC to the comfort of family. When Christmas came, like good American Jews we went to the movies. And there, while getting popcorn, my brother pointed out that the man who was assigned to watch my dad’s casket for days and nights before his burial was working at the ticket counter. I couldn’t focus on the movie and pretended to go get some candy, but instead went in search of this man.

When I finally found him, I thanked him, deeply, for being with my dad and his spirit.

I was standing at a popcorn stand. At the movies. On Christmas.

My father’s death was everywhere I went.

Even though burial rituals and visits to the mourners had ended, my grief was still very much alive.

Was it true that I was ready to stand alone?

Expect error, recalibration, to not know 100 percent what you need. Like a crying newborn, you are a wild landscape of new and unpredictable needs, and it’s fair to not be able to foresee exactly how to soothe yourself in this early stage of everything-is-a-total-incomprehensible-emotionally-charged-messy-wild-horrible-touching-disaster grief. This lack of knowing your own internal terrain can wreak havoc on relationships.

There will be false starts. Forgive yourself—and then cocoon.

Climb into your bed. Pull the covers over your eyes. Get in the fetal position. Breathe.

When I stepped in error, I leaned, steady, into the timeline of grieving Judaism set up for me. You don’t need to be Jewish to glean meaning from these time markers: like a semester in college, these periods of 7, 30, and 365 days helped me to calibrate my specific experience of mourning, to pause and re-evaluate shifts and changes within me, to mark the constant evolution. Having a slight handle on what I was going through, or a remedial map of the depth of mourning I was supposedly in, helped me find some peace in my relating to others—it helped me give myself permission to take space, ask for what I needed, and to rest where I could find pockets to do so.

I suggest marking time according to your markers of death, burial, cremation, birthday of the dead—whatever is your whim—and using those time markers to notice how your cycles of mourning shift. These time-based practices, older than me and my dad combined, bear wisdom. They are pivot points, markers of transition, and allow for places to pause, look around, and assess whether things have actually evolved. For me, at every marker, my grief certainly had evolved, until I felt almost normal again. This helped me process my grief in immeasurable ways.

Come January, one thirty-day grieving cycle after my father’s burial, I resumed my life alone in New Orleans in my home. No one was sending packages anymore. The calls stopped. So did the food deliveries. Suddenly there’s this territory with no funeral, no anniversary, and less coddling, less asking after you. I was on my own. I had to remember to eat. I had to remember to cook. I had to make my own tea.

I was on the phone with a friend while hunting my own desserts because cake stopped being delivered to me. No more carrot cake. No more babka. No more sweets on my doorstep at all.

“Maybe,” he told me, “now that it’s not showing up at your doorstep, it’s time to stop eating the cake.”

I hated him for saying it. I bought two cupcakes instead of one just to spite him.

But he was raising an important point: What do we do, how do we shift, when the immense amount of care for the griever subsides?

Cupcakes turned into a cautionary tale of the transition from excess to temperance, from the time to lie down, to the time to sit up.

I missed my family.

I missed being a griever that people cared for.

I felt suddenly very single and deeply alone.

I knew I needed to start calling on my strength again, and on the strength of my community.

Asking for help now, postmortem, post-life-altering loss of any kind, is different than it was earlier. People aren’t going to sprint over with a casserole. They aren’t crowd-funding for the funeral. They aren’t even mobilizing for prayers. The acuteness of your needs have, at least to the naked eye, subsided—though that may very well not be true for you.

In fact, in my incubated state of extreme collapse, I had come up from the earth with a whole new part of me exposed and, as a result, had a whole new set of needs. Now, after the burial, after family time, alone in the netherworld of months two through nine after my father’s death, when asking for support or needing it, I had to ask for new things, draw new curtains, and say no to things that used to be normal for me.

Be ready in the first few months after a great loss to greet your new self.

Be ready to embrace the shifts inside of you and the wildness to soon emerge.

Be ready for this to change your relationships, your needs, your asks, all of it.

Friendships after a death can be challenging.

The second month after his burial was a fraught time of no formal assistance and total fragmentation of my emotional world. Everything under the sun in my life had changed. My bed. My city. My job. My doctor. My friends. The immortality of my dad. And now the ebb and flow of baked goods and care packages too. The space of life after the death of a parent required recalibration at every single turn. Suddenly, I was in phase 567,884 of mourning. The last-week-was-hell-now-how-do-I-measure-this-less-intense-but-nonetheless-ridiculously-hard grieving stage.

And while I had just been taken to the brink, witnessed something life altering, and navigated the depths of my own despair, a lot of my friends had been going on with things at a normal, less intense pace. If we were the same before, now many of us were not. I lived alone, I did not want to also feel alone while speaking to my friends. I needed my experience of death honored, marked, and made space for inside of conversation.

Many friends who were by my side in my time of loss as my father was dying were less equipped to handle the landscape of after-death loss. Many of those who comforted me profoundly when my father was dying felt like foreigners once my father was actually dead. They didn’t share my lived experience. And I felt they didn’t have the tools to share equally in basic conversation: I knew the very thing I was going through was the biggest fear for so many. The loss of a parent is horrifying, and I was living it.

Thirsty for unfettered connection, and eager to dodge the possibility of handling other people’s fear in the midst of a conversation about my life, I found myself asking close friends questions like, “Have you ever seen a dead person?” and “Have you ever been in the room when someone died?” I was separating out those who could understand the gravity of what I had been through, and those who could not. Those for whom projection or imagination was a means of connection, versus those who, deep in their gut, simply knew what I knew.

I called random people from my life, often not understanding why at first, only then to suddenly be deeply entwined in intimate conversations about the loss of a parent. It was as if I had a new sixth sense for those who knew what this pain was. And, a new aversion to those who did not.

Don’t be ashamed of needing new company, or of finding that friends who were once comforting are suddenly out of touch with your reality.

You have gone through a sea change.

Rather than offering pithy (though kindly intended, I know) comfort, such as “your dad is still shining down on you,” I wanted my company to just sit with the facts as I experienced them: My dad was dead. I didn’t need to paint that with rose-colored glasses. I watched it happen. I buried him.

I remember when my friend Giulia’s mother passed away, and I went over to her house with care items, hoping to comfort her. I also remember being terrified of her pain, so frightened by what I was seeing, and, consequently, terrible postmortem company. Not until my father died did I understand how medicinal fearlessness is for the griever, and how burdensome other people’s terror becomes.

“All things happen for a reason.”

“He can hear your prayers.”

“Your father is in heaven now.”

“Isn’t it nice, he’s up there with your grandparents!”

All said with good intentions, these ideas felt to me like side steps to the burden I was facing.

My dad’s heart stopped beating in front of me.

My dad had made his last sound.

I closed his eyes.

I watched his body taken to a freezer.

I witnessed a massive concrete plate get lowered over his casket.

I scattered earth over his dead body.

I was concerned with the stuff of mortality. The basics of a Dead Dad. Anyone who wanted to convince me otherwise felt like they wanted to deny my reality.

“An odd byproduct of my loss is that I’m aware of being an embarrassment to everyone I meet,” C. S. Lewis writes in A Grief Observed. “Perhaps the bereaved ought to be isolated in special settlements . . . To some I am worse than an embarrassment. I am death’s head.”

Grievers, like single people, are vectors.

They are vectors of the things we are taught to avoid, to loathe, to fear. In this case, it is parallel to the feared aloneness of the single woman. Grievers confront those they encounter with the prospect of:

• Death.

• Sadness.

• Suffering.

• Pain.

• Loneliness.

• Dead loved ones.

The funny part is: No one gets out alive, everyone will die, and yet we are asked to live in a fantasy where we do not admit death, nor the acute pain that follows for the living. Everyone on earth experiences this horror, yet we are not taught or trained to navigate the abyss.

The boundaries for what I could stand as well as what I wanted to guard had all changed . . . and that means the things that set me off had changed too. Like clockwork, conflict followed.

Volatile means “easily evaporated at normal temperatures.” It means “liable to change rapidly and unpredictably, especially for the worse.” As a volcano, and a very active one, myself, it was vital to try to mitigate the blending of my hurt with someone else’s: Two people’s trauma could so quickly become an unpredictable explosion. When my father died, I could only tolerate the most genuine, sweet, caring, loving people. If you were even slightly annoying, self-involved, dissociated, or anything but fully present to the sacredness of loss, I honestly excused myself from the room.

If someone rubbed me wrong, I went zero to one hundred in no time.

This is common after-death behavior.

Your loss, your trauma, and the death of a loved one, all will make you more easily moved to anger, frustration, and sadness. There is a roiling hell just under the surface that’s likely always willing to bubble up and rattle your relationships. It’s good to know that this chaos is coming, to plan for it, and to know that as scary as it may feel, and as strangely resistant as others may be at times, it is 100 percent OK to talk about it.

I had rage, and not just rage about the death and dying of my dad, but rage about old untended griefs galore. Old wounds, in this new bottom-of-the-barrel state of honesty, were raw and real and here and refusing to be hidden. Trauma will rattle the body. Death will shake the nerves and rip any veil, any secret loose.

What you could ignore before, good luck hiding now. Plan for volatility.

And plan to prevent it.

Yes, even you can prevent emotional eruptions.

The more we treat grief and mourning like basic needs that must be met, the less, as my old landlords in Oakland cautioned me, “crazy gets to drive the bus.” Would you put your furious three-year-old in the driver’s seat and cruise through the city? Nope. You would keep them in the back seat and wait for the tantrum to subside. When we’re grieving, we are at times like a tantruming child.

We need to do little doable things in this tender time to mitigate our proclivity towards explosion.

For example, I ate cake (duh) all the time when my dad was dying. I needed it. It was my drug. And, sugar makes me angrier than usual, quick to react. If I could go back in time, I would have added more vitamins to my regimen. I would have added more water. And maybe asked a friend to stretch with me a couple times a week. Something to break up the sugar’s control over my emotions. But to not have sweets, in such a horrible time, that would have been too punishing.

Instead of unrealistically eschewing alcohol, sugar, or whatever your vice may be, (I support you and your twelve-step program too, this is not about sincere addiction, rather about temporary bad habits) buy a lot of water and keep it in the car for after-hospital visits. Have protein bars, whatever vitamins and minerals are safe and fortifying for your system on hand. If you drink to cope, it will also increase the possibility of anger and reactivity. So balance whatever your vice is with remedies that lessen the possibility of volatile explosion. These little things could prevent a mountainous explosion, or at least reduce it to hill size.

Just because you are ready for a raw conversation, ripped open by death and loss, doesn’t mean others in the room are, nor does it mean they have the emotional tools for said emotional conversing. Stay in your corner of the ring.

Go easy on others, and go easy on yourself. Save your sacred words, thoughts, reflections, and wisdom for those worthy of it, for those able to deeply hear your messages. And forgive yourself if you explode on occasion. You are hurting.

The best and most vital ingredient to relationships after a death are as follows:

1. Be realistic about your state of distress.

2. Be realistic about your wants and needs.

3. Be realistic about the actual emotional capacity of those you encounter.

Ask yourself, even in times of acute pain and deep loneliness: Why am I calling this friend? Do they have the tools within them to hear me, comfort me, meet me where I am?

Knowing in advance what it is that is driving you, and what it is you seek, will serve to protect you in your highly vulnerable state. Why are you calling them? Is it to fill the void of pain and sadness? Is it because they understand your experience? Is it because you know you can be with them in a quiet, real way? Or perhaps because you know they can be a positive distraction from the pain? Slow down before pushing send, before calling, and check in with yourself.

Come back to your five things. Sink into your bones.

You don’t want to spend the days of sacred processing cleaning up emotional messes and navigating further guilt and shame on top of grief. You want to fall down, cocoon, release, and get the fuck back up again.

Hopefully, in time for next Mardi Gras.

Excerpted from Forget Prayers, Bring Cake: A Single Woman’s Guide to Grieving. Merissa Nathan Gerson, © 2021. Reprinted with permission of Mandala Earth and Insight Editions, L.P.

Merissa Nathan Gerson is a writer, sex educator, and rape prevention advocate. She teaches Alternative Journalism at Tulane University in New Orleans.