My Abortion, My Miscarriage, and My Right To Have My Own Feelings

Women are entitled to a wide range of emotions about their bodies and fertility. But under Jewish law, the rules are clear.

In my 20s, I had an abortion.

I was blissfully in love with the man who would become my husband. We’d been friends for a year, secretly pining for each other the entire time, and we’d finally begun dating despite living on opposite coasts. We’d been a couple for six weeks. The condom broke. Then the morning-after pill didn’t work. (This isn’t uncommon—emergency contraception turns out to be pretty crappy at preventing pregnancy; a recent study found that its effectiveness, once thought to be around 75 percent, actually ranges from 47 percent to 53 percent.) I was working for peanuts at a magazine I knew was going to close. I had a cat, a bike, uncertain job prospects, and no savings.

Jonathan flew to New York to be with me for the procedure. He stayed two days. He made me spaghetti with olive oil and hot pepper; I lay on the couch; we watched TV; and then he went back to San Francisco. I felt only relief about not being pregnant anymore. I was not ready to get married (though I strongly and correctly suspected that Jonathan was The One), and I was not equipped to have a child. I went back to work. Jonathan and I continued to date long-distance. When my magazine folded five months later, I moved to California. Jonathan and I lived together for a year, then got engaged, then got married, then moved to New York, then had Josie and Maxie. We’ve been together almost 17 years now.

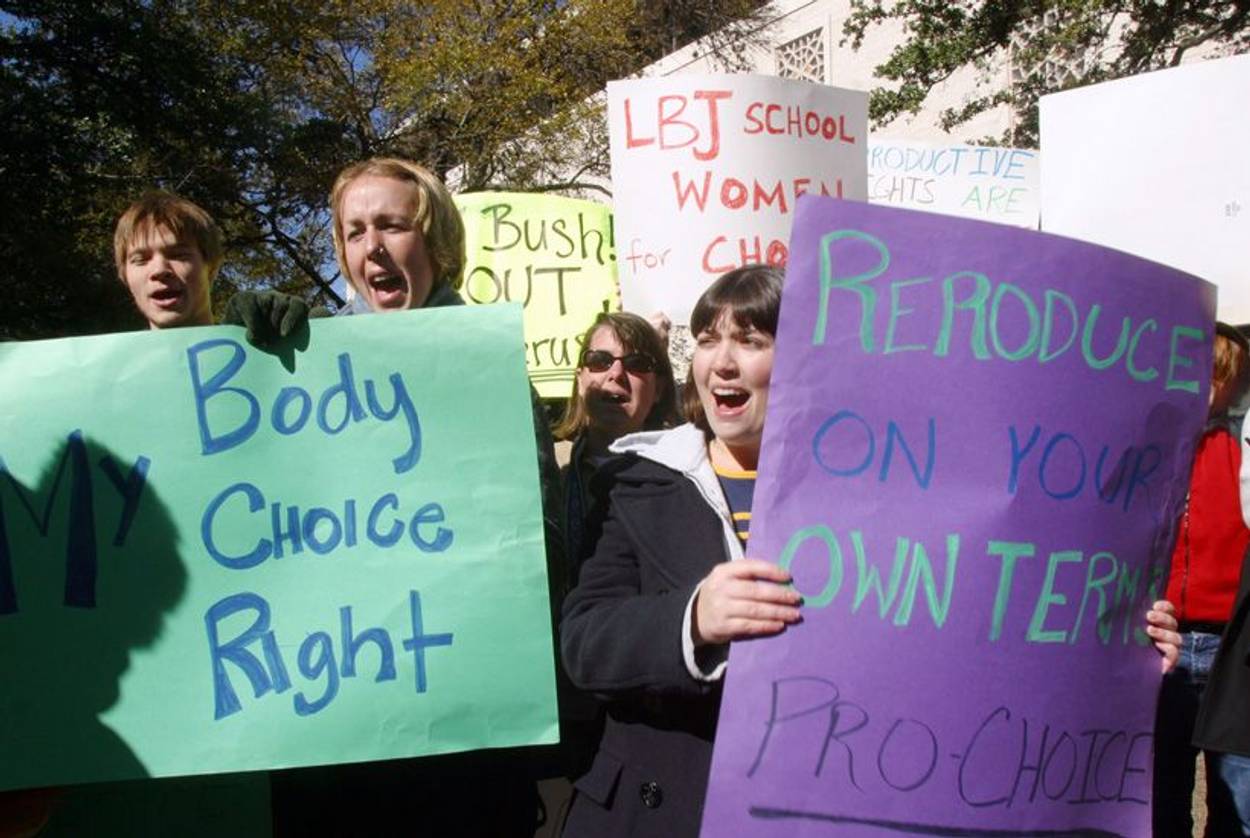

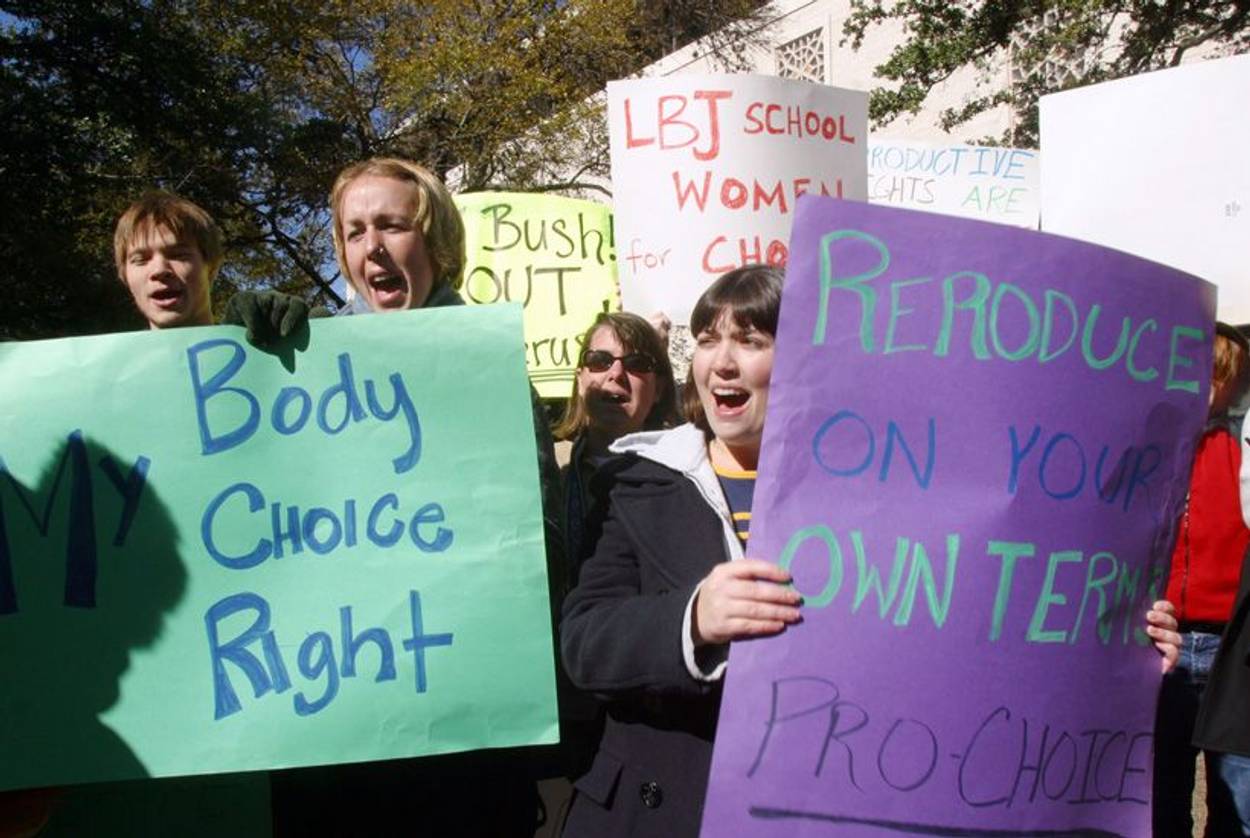

I rarely think about my abortion. I was pro-choice before it; I’m pro-choice now. And the experience hasn’t been something I’ve been eager to write about. Sarah Tuttle-Singer bravely wrote about her college abortion for Kveller, and the venom aimed at her on the Internet would curl your hair. I didn’t want to be a target that way. But then I thought about Jessica Grose’s recent piece in Slate about how first-person abortion stories in the media “are almost always about ‘appropriate’ abortions. Shrouded in mournful tones, regretting the baby that couldn’t be, reflecting on that upsetting choice.”

Grose pointed out that these experiences aren’t most women’s reality. A third of American women have had or will have an abortion; we are not all devastated by the experience. And it’s important for us to tell our stories, too. Hey, abused women and poor women and women who desperately want children but discover they’re carrying a fetus that will be born with a fatal, painful, genetic disease still get attacked as baby-killers. I’d like my perspective, as someone who is not haunted, to be out there, too. Tuttle-Singer shouldn’t have to take the heat alone. So, go ahead and curl my hair, haters. It’s already pretty wavy.

So: I rarely think about my abortion. Sometimes when I’m marveling that Josie is so grown-up, I try to calculate how old a child I’d have if I’d let that long-ago pregnancy go to term would be. I can never quite remember. The date is not seared into my memory.

I do, however, vividly remember my miscarriage. It’s not that I ponder it incessantly; most of my ruminating these days is about what to make for dinner when I forgot to buy the broccoli and how I need to get Maxie a new school backpack and when I’m going to be paid for that farshtunkiner women’s magazine story and how I need to find time to work on that piece about fat kids in children’s literature. But sometimes I flash back to how ineffably sad I was, how fiercely I’d wanted that pregnancy. In general, remembering the saddest time in my life (except for my father’s death) helps me feel empathy for other women’s pain—empathy I think many anti-choicers lack.

It was the year before Josie was born. I was just on the edge of my second trimester, 11 or 12 weeks along. Jonathan and I were supposed to leave that morning on our first vacation in ages. But in the middle of the night I’d started to bleed and didn’t stop. I had my second procedure then—I suppose, technically, it too was an abortion—because my body didn’t expel the entire fetus on its own. I lay on the couch a lot longer after that one, and not just because the pregnancy had been further along. I cried constantly. I lashed out at well-meaning friends who said dumb, well-meaning things like “Don’t worry, you’ll get pregnant again.” (You know this how?) Jonathan didn’t know how to help me. And I hated myself for being so upset.

No matter what we feel—sadness at a miscarriage, relief at an abortion—women are told their feelings aren’t legitimate. Someone—a politician, a friend, a member of the clergy—invariably tells us to buck up if we’re devastated by the loss of a wanted pregnancy, and/or to hate ourselves if we’re not devastated to end an unwanted one. Jewish law, however, is about rules and remedies, not emotions. In our tradition, babies who lived less than 30 days weren’t considered full-fledged people. “We do not mourn for fetuses, and anything which does not live for 30 days, we do not mourn for it,” wrote Maimonides in his Laws of Mourning in the Mishneh Torah. “The infant, for 30 days, even including the full 30th day (if it dies), we do not mourn for it,” said the Shulhan Arukh. That’s pretty clear and stark.

But today, Jewish tradition encourages women to mourn if they want and need to. Jewish feminists have created rituals, poems, and prayers for miscarriage. And I was surprised to read in Josie Glausiusz’s recent piece in Tablet that there’s a similar movement happening with abortion. Three founders of Mayyim Hayyim, a Massachusetts mikveh, wrote a ceremony to help women work through the decision “to interrupt the promise of life.” (The writers are a poet, a psychologist, and a rabbi.) The ritual opens with a kavannah—the “intention” by which a person prepares herself to do a mitzvah in the fullness of her heart. I find this strangely beautiful. Conservative Rabbi Amy Eilberg also wrote a post-abortion ritual, out of “a general Jewish feminist awareness that the tradition was created substantially by men . . . who didn’t necessarily know what women, if they had agency, would want to have included in the tradition.” Rabbi Tamar Duvdevani wrote a ceremony, too, this one influenced by the Rosh Hashanah tashlich service.

I love the idea of women having the option to mark events—positive or negative—with ceremonies that bring meaning to their experiences. But I don’t think I personally would have needed these rituals when I chose abortion. I felt no ambivalence. I needed no validation. My point is that we’re entitled to a wide range of feelings when it comes to our bodies and our fertility.

But again, Jewish law is not about feelings. Which is why it’s important to repeat here that Jewish law is rather clear on the fact that abortion is not murder.

The Torah and Talmud commentator Rashi wrote of the fetus, “lav nefesh hu”—it is not a person. The Talmud says “ubar yerech imo”—the fetus is as the thigh of its mother. It’s part of her body, not a separate human entity. These statements derive from a passage in Exodus saying that if two men are fighting and one winds up pushing a pregnant woman and causing her to miscarry, that man needs to pay a fine, but it’s not “a life for a life.” Jewish law interprets this to mean that the fetus doesn’t have the same legal status as the mother, a full-fledged, autonomous human being. The Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice adds that the legal principle that the fetus is part of the woman’s body is backed up by one of our tradition’s many delightful rules about livestock. In the Talmud it says that if a guy sells a cow he later learns is pregnant, he can’t get further compensation from the guy he sold the cow to, because that wee bovine fetus is part of the cow’s body. And then there’s the rule about how if a pregnant woman converts to Judaism, you don’t do a separate conversion ceremony for the fetus, because it’s part of her. The RCRC also discusses the texts that call a fetus that threatens a woman’s life a rodef, a pursuer, that she must be saved from. Of course, for anti-choice people, there’s always the question of how threatening that pursuer actually is. Do we need proof that she’d die in childbirth, or is it sufficient that she might kill herself later? Exactly how depressed does she have to be to warrant an abortion?

Some rabbis—mostly Orthodox ones—do not think any reason but an actual physical threat to a woman’s life is a valid reason for abortion. Some rabbis—including some Orthodox ones—would still argue that a woman’s emotional health is a valid reason for abortion. There is diversity of opinion. And although nearly 75 percent of the American Jewish community is pro-choice, even spiritual leaders who wouldn’t legislate against abortion aren’t entirely supportive of women, you know, having abortions. I literally gasped at the quote from a Conservative rabbi in Glausiusz’s article on abortion rituals saying that if a woman “has to terminate a pregnancy due to her own physical and emotional health crisis, or because she was raped, or because the fetus was terminally ill,” then acknowledging the event with a ritual might be all right, but only in “one of those regrettable instances when one terminates a pregnancy for responsible and defensible reasons.”

There are two problems with that perspective. One is that a rabbi is a spiritual leader; it’s hard to feel spiritual and pastoral support from someone who you suspect thinks your choice is irresponsible and indefensible. Because when you know he thinks other women’s choices are irresponsible and indefensible, it’s legitimate to wonder what he might secretly think of yours. The other issue is, of course, that abortions happen no matter what. (At my 15th college reunion, I chatted with a friend who’d become an OB-GYN and performed abortions as part of her practice. She told me that several of the protesters outside her clinic had come to her for abortions—for themselves or their daughters—and then went right back to protesting.) It would be lovely to get rid of the shame and hypocrisy, the notion that you have to be really, really sad to deserve an abortion, the notion that other people’s abortions are wrong but yours is necessary, the notion that if we just make it exceptionally hard to get an abortion we’ll create a better world for women and children.

Because the second problem with putting up barriers to abortion is that when abortions are illegal, women die. And when abortions are inaccessible (by distance, anti-choice laws, parental notification requirements), unwanted and under-cared-for children are born. (Please don’t get me started on the simplistic “just put it up for adoption” comment. Saying “just put it up for adoption” is like telling me “don’t worry, you’ll get pregnant again” after I miscarried. Yes, this comparison is ironic. But the reasons for the idiocy of the comment are the same: You have no clue about my health, my finances, my relationships, my body.)

I keep coming back to one of the prayers from an abortion ritual discussed in Glausiusz’s story. “May the One who blessed our foremothers, Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel, and Leah, bless, heal, and renew [woman’s name]. May the Healer give her support and strength, patience of spirit and courage.” To me, it’s striking that this prayer is fitting for both abortion and miscarriage. It invokes the strong women of our tradition, and it asks for what we need to withstand the cruelty—both deliberate and unwitting—of people who presume to know our bodies and lives better than we do.

Marjorie Ingall is a columnist for Tablet Magazine, and author of Mamaleh Knows Best: What Jewish Mothers Do to Raise Successful, Creative, Empathetic, Independent Children.

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.