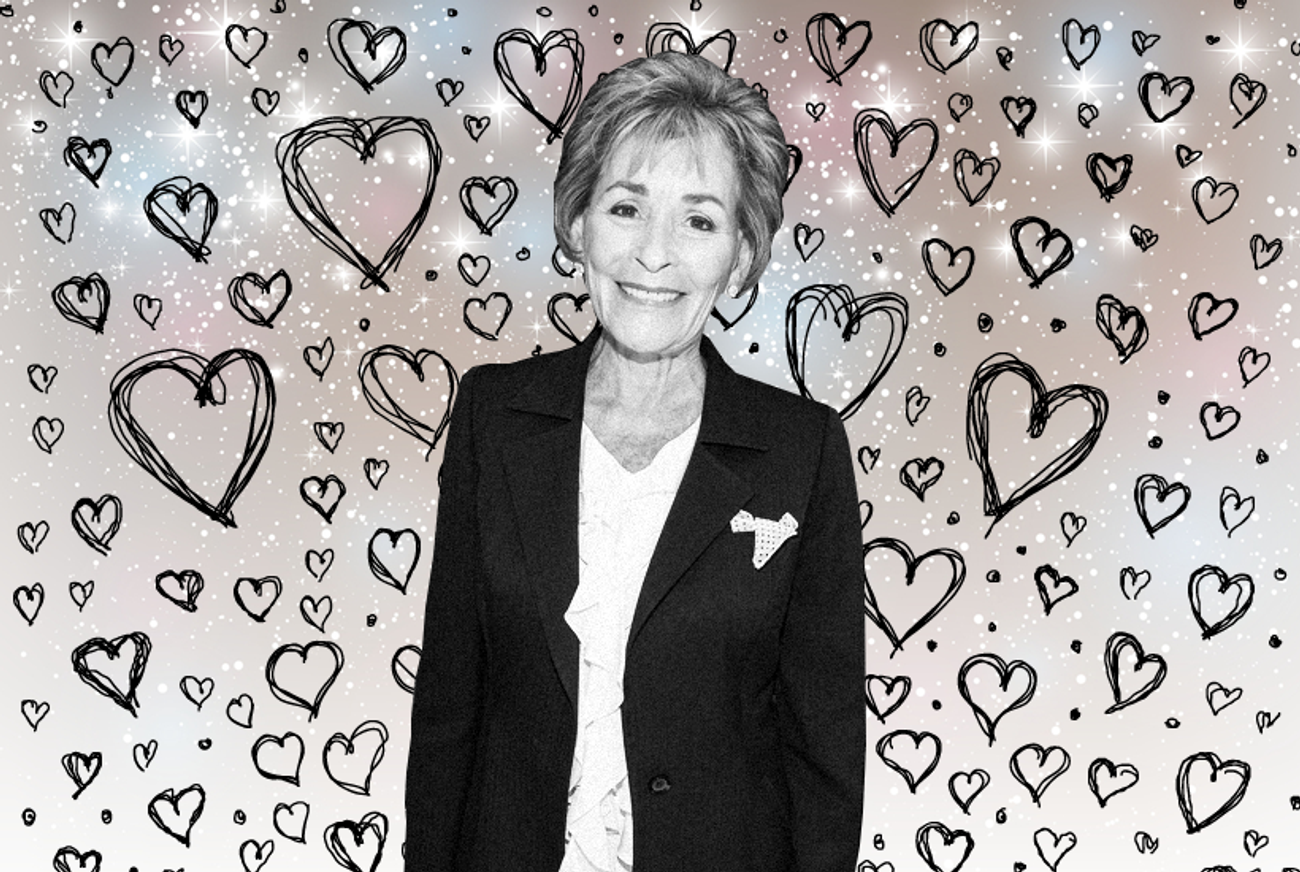

Meeting Judge Judy—America’s Jewish Mother

TV’s most popular judge always reminded me of my mom. Last year, the two ‘no-nonsense broads’ met in person and hit it off.

At a fundraiser last spring, I bid on and won the chance to attend a taping of my favorite TV show: Judge Judy. I have admired its star, Judge Judith Sheindlin, for the show’s whole run—nearly two decades. After all, this is the woman who told some particularly audacious litigants: “I eat morons like you for breakfast.” Her attitude reassured me that in a world full of scammers and nudniks, there were still people who exercised the same kind of no-nonsense approach to life that was a cornerstone of my upbringing.

In other words, she reminded me of my mother.

In the spectrum of Jewish mother prototypes, mine manages to embrace her cultural charms while avoiding the stereotypical behavior that would make me want to strangle her. Meaning, she doesn’t harass me about the fact that I’m single, childless, and overweight. She is happy to consider my dog one of her grandkids. But no one would accuse her of timidity. She’ll gladly tell me where I went wrong in my attempts to copy her chicken soup, or why I should stop complaining about my job. “What would you rather do? Live on the dole? Or quit and move back home? Who says I’d let you?” she’ll say to me, with Judge Judy-style bluntness.

Naturally, my mother is also a Judge Judy fan. So, when Armando from the show’s production team contacted me and said that I could bring a guest, there was no question that my guest would be my mother. We scheduled the visit for November, shortly after she celebrated a milestone birthday. This would be her greatest present.

In addition to seeing the taping, we learned, our visit would include a meet-and-greet with the famous jurist. As the date approached, the thought of actually speaking to the woman whose Brooklyn bark resonated in my Los Angeles living room weekday afternoons filled me with a combination of joy and nervous excitement that made me fret about every aspect of our forthcoming encounter.

What would I say to her? “Nice to meet you. I’m a big fan,” felt ridiculously clichéd. But blurting out, “I love you and hope we become friends who text each other pictures of our dogs,” was a major boundary overstep. I wanted to show my appreciation, not behave in a manner that would put me on the receiving end of a psych evaluation.

When I considered what to wear, my pulse thumped, and I mentally vetoed half the clothes in my closet. Armando said that business casual, even denim paired with a blouse, would be fine. It took every ounce of self-control not to tell my mother how to dress. As if my modest, smart, and accomplished mom would have showed up in a tube top. I was overthinking this.

The morning of the big day, I paced in front of my complex, waiting for Mom to pick me up. Morning rush hour in Los Angeles was not our friend, but I needn’t have worried. My mother is chronically punctual—in our family, there is no such thing as Standard Jewish Time—and we arrived at Sunset Bronson Studios five minutes early.

Armando answered all of our questions and used my iPhone to snap lots of staged pictures throughout the show’s set before taping began. In several shots, Mom and I pretended to be plaintiff and defendant, fighting from the litigants’ respective tables in the TV courtroom. Once we were seated in the front row, the stage manager had instructed the audience, mostly comprising paid extras, to pay attention during the cases and keep our eyes open so we wouldn’t “look drunk.”

Sheindlin walked in and began to adjudicate the first case. I tried to soak in every moment while I watched her berate a college student whose voice quivered as he tried to remember how many roommates he had. It was a little hard to hear. The participants wore microphones, but their voices were amplified for the purposes of television production, not live theater.

During the short break before the next case, Mom said, “Did you notice when she left the set? She’s wearing jeans.”

“Cameras are still rolling,” I hissed. “We’re supposed to be making fake small talk, not staring at her.”

After the next case, I asked my mother if she was enjoying herself. “Yes, but I like it better when you can hear the music and see everything from all angles,” Mom said. “Like when I’m watching it at home. That’s what makes it fun.”

“Surely, you didn’t think we were going to get all the production value while we were here,” I said. “That’s why this is so frigging cool. We’re experiencing Judge Judy in the raw.”

After sitting through a few more cases, Armando asked us to take out our phones again because it was time to meet the judge. Blood banged against my cheeks as we walked through a darkened studio hallway. I made a mental note to not say anything stupid.

We shook hands with Sheindlin, and Armando took our picture. I blurted out my practiced praise but was drowned out by the commotion of stagehands passing through the area. I knew she didn’t hear me, but at least we got a photo together, lasting proof of this memorable moment, which I later had made into a mini-poster that hangs in my office.

Mom caught her attention, though, and in the space of our 30-second greeting, lauded her for making mincemeat of all the deadbeat litigants who filtered through her TV courtroom, specifically referencing the case we had just witnessed.

“I know we don’t know each other, but your America and my America are the same America,” Mom declared. “I wish it were everyone’s America.”

The judge gave her a knowing nod before heading back to her made-for-TV bench.

“Holy cow!” I whispered. “You and Judge Judy just totally shared a moment.”

Later, we joined the production crew in the commissary for lunch. Mom jabbed my arm, pointing out that Sheindlin was sitting just one table over, eating with everyone else. When we finished lunch, Armando asked us to hang out for a minute.

Then something totally unexpected happened. Sheindlin got up from her seat and walked over to join us at our table. Just to kibitz. I almost plotzed.

“Lunch wasn’t very good today,” she said to Armando. “Fried chicken. Uch. Very fattening.”

She turned her attention to us. “Did you have fun?” she asked.

I answered quickly, “Yes, and I meant what I said when we met downstairs. My mom is my hero. And so are you. You are the two women in the world I admire most.”

“Well, then, you must like, tough, old, no-nonsense broads,” Sheindlin said.

I nodded, grinning dopily, like the kind of star-struck fool I usually mock.

For the next 15 minutes we sat chatting with her … about dogs! Just like I had imagined. Well, not quite. No phone numbers were exchanged. Mom told stories about boiling fresh chicken every night for her Great Danes, and how they broke her heart when they died. Sheindlin commiserated, talking about her past and present shih tzus.

Just for a moment, watching the two women I hold in the highest esteem banter with the ease of old friends fed my ridiculous fantasy that this was anything more than a one-time shot. Eventually, Sheindlin stood up, shook our hands again, and excused herself to confer with the director. Clearly, it was an otherwise, humdrum business as usual day for the greatest judge/TV star on the planet.

On the car ride home, I could hardly sit still.

“Well, that was all kinds of awesome,” I said.

“Wow, you really had a good time,” Mom said. “I haven’t seen you this enthused about anything in a while.”

“So did you,” I countered. “You commandeered the whole conversation with her.”

“Yeah, I guess I did. She’s very nice and much more personable than I would’ve expected for someone in her position.”

I smiled. To people who don’t know my mom well, she too can be a bit terrifying. When I was 9, she screamed at my elementary-school principal for commenting on the contents on my lunch. A few years ago, she almost caused a security incident at a Hawaiian airport when the airline had a problem with my boarding pass. She has never let anyone push her around in the male-dominated industry in which she works. But underneath that sometimes-intimidating demeanor, my mom is the most generous, open-minded, and caring person I know. And though she never said it, I knew how much it pleased her when I compared her to Sheindlin, my second-favorite Jewish mother.

Erin Auerbach is a writer whose work has appeared in the Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, and Salon.