Messages in Stone

A new study of old Jewish cemeteries in Europe finds the epitaphs whispering at us

On page 236 of Metropolitan Jewish Cemeteries of the 19th and 20th Centuries in Central and Eastern Europe: A Comparative Study, a talmudically discursive new survey from Rudolf Klein, in the upper-left-hand corner, there is a photograph of a gravestone. The stone, which stands in the Jewish Philanthropy Cemetery in Bucharest, is tall, with an unconventional top, a “semicircular arch and simplified angled acroteria.” Beneath that semicircular arch, two carven hands meet in a warm handshake. The epitaph on the stone identifies the deceased as a hatmaker who lived between 1832 and 1892. It describes him in the Hebrew as an “ish yakar,” or dear man.

And what was this dear man’s name?

Adolph Hittler.

There is, of course, no relation. It seems that this Romanian Jewish hatter lived out his 60 years in esteem and respect, without any notion of the ignominy that his name would come to bear. Only in the dubious illumination of historical posterity does the cruel joke become clear.

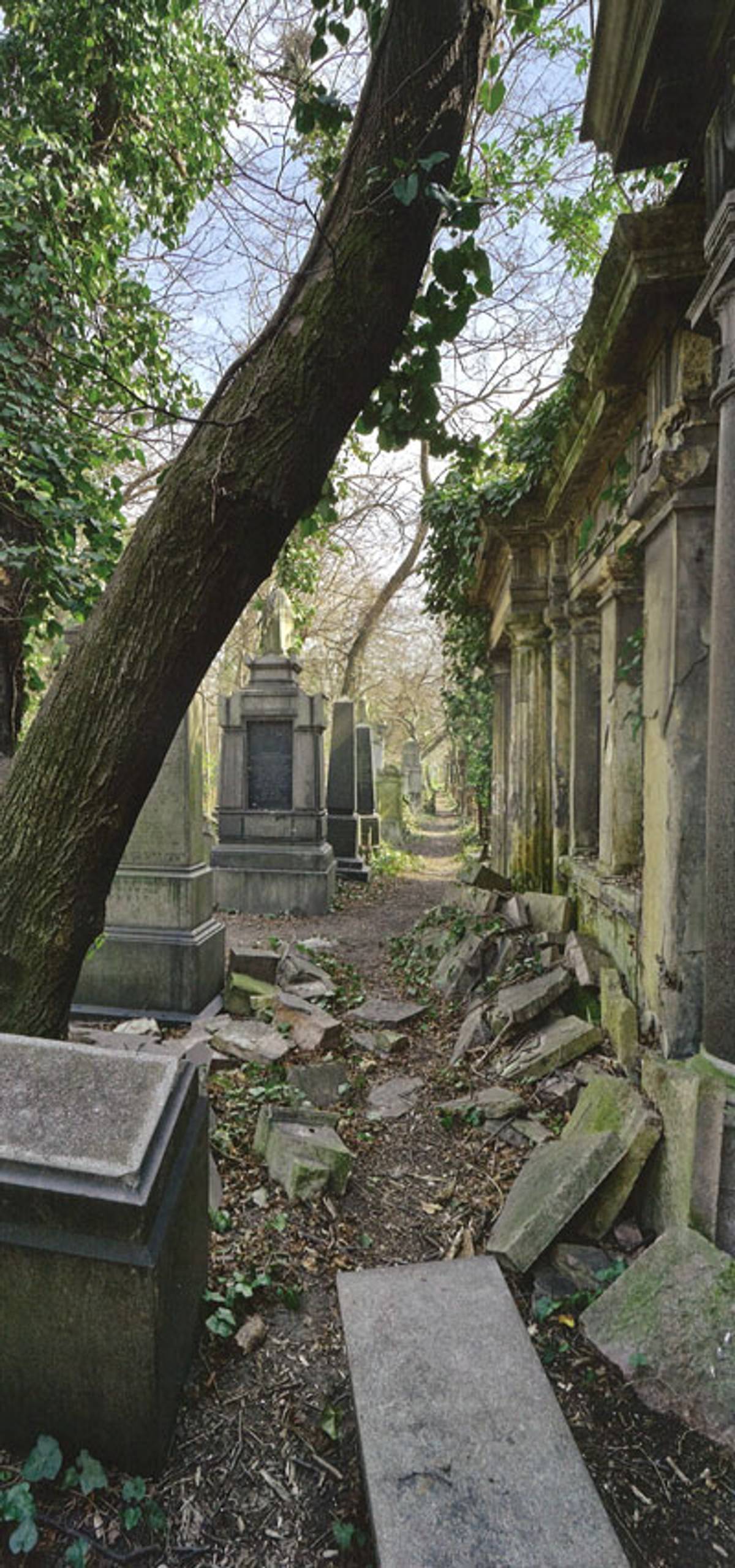

This feeling, this ironic hindsight lingering somewhere between crassness and sublimity, as if Larry David and Franz Kafka were jointly responsible for the long arc of Jewish history, pervades the experience of thumbing through Klein’s book, which is full of photographs of graveyards—their paths and byways, monuments and markers. It’s nearly impossible not to see these graveyards, these weighty, permanent, stone necropolises, through the lens of intervening European Jewish history—a history of massacres, pogroms, ghettos, murder. In this light, these cemeteries seem like a series of monumental mistakes, like huge stone beds neatly made in the cradle of a trap.

After all, the cemeteries here are specifically of the urban 19th and 20th centuries. The Jews buried within them are not the fiercely traditional European ancestors so commonly imagined by contemporary American Jews—poor but plucky in their timeless shtetls. These are, rather, the Jews who embraced their full citizenships in what they thought was a newly open world. Their proud emancipation seems, with the benefit of hindsight, to be the most horrific gotcha in history.

It can even feel tempting to cast these cemeteries as artifacts of a kind of hubris: You believed the Germans, the Poles, the Hungarians, and Romanians when they said you were equal, and this is what you got. Because not even the splendid monuments of the well-to-do religious reformers escaped the ravages of the 20th century—an entire chapter of Klein’s book is devoted to “damages caused by wars, Nazi or Communist destructions, neglect … and profiteering.”

But this line of thinking—this kind of internalized gaslighting—is what Hitler (one “t,” this time) and his eugenicists wanted. The Jews buried in Klein’s cemeteries were fully German, Austrian, Polish, Romanian, Lithuanian, Hungarian, and Russian, and no one’s hate—no matter how thoroughly they legislate it—can change that.

So much of European Jewish life seems to have been overwritten by the tragedy of the Holocaust. But Jews lived—and importantly, also died—in Europe for generations, and they left behind monuments, cemeteries, and headstones for us to see and interpret when they were gone. We must, of course, continue to remember the tragedy of the Holocaust. But I think we do our ancestors a disservice if we study the Nazi deaths at the expense of the Jewish ones.

*

What, then, might we learn from the way that the 19th- and 20th-century Jews of metropolitan Europe memorialized their deaths? In this formidable book, Klein, an architectural historian at the Szent István University in Budapest, has collected and analyzed an extraordinary breadth of examples. What can these cemeteries tell us about the lives and Judaisms of their occupants?

The major unifying factor throughout Jewish history may well have been one God, but in no period has there ever been one Judaism, and the cemeteries expounded upon in Klein’s book demonstrate this decisively. The diversity in approach, particularly with regard (or in some cases, disregard) to traditional religious law, is vast.

At the Žižková Street Cemetery in Bratislava, for example, the organizing principles are highly traditional: The graves are marked with vertical slabs grouped in loose lines. The stones bear few figurative markings. Decoration is abstract where it is present, and the defining visual elements are the bold cornered shapes of Hebrew letters. Even the setting is stripped back to the barest essentials; the grass grows thick between the graves on the hillside, and the wide Danube River rolls by to the south.

By contrast, the Weissensee Cemetery in Berlin is one massive departure from tradition. It is scrupulously planned, laid out like an urban pleasure park, with paved diagonal lanes providing orientation for the graves rather than the traditional East, toward Jerusalem. The graves here are predominantly marked in German, rather than in ancestral Hebrew, and huge monuments abound, designed to decidedly non-Judaic aesthetics: Romanesque columns and arcades, grand Teutonic mausoleums. There’s even the occasional Egyptian motif.

In fact, after flipping through Klein’s book, one comes away with an impression of decided Jewish diversity, and not just between disparate rites—even within discrete communities. We can often fall into the habit of thinking of our Jewish forebears as generally unified in their approach to religious law, but the cemeteries here tell a very different story.

To take another example: There are several verses in the Hebrew Bible prohibiting the manufacture and worship of idols. These verses are most often interpreted as a wholesale ban on the engraving or sculpture of any image, natural or divine. But some understand these verses to prohibit figurative art entirely, no matter the subject.

In certain of the cemeteries in Klein’s survey, this traditional prohibition is largely honored. Only the most customary symbols are employed, and then only in simple, two-dimensional iterations: a pair of hands upraised in benediction to denote a Kohen, a simple handled jug for a Levite.

But other graveyards, such as the ancient Battonstrasse cemetery in Frankfurt, seem to have cultivated a distinct system of images to adorn their gravemarkers. Even angels, in violation of the halakhic proscription, are represented.

And at the furthest end of the spectrum, detailed depictions of the human form, the most widely prohibited of all figurative images, are not too hard to come by. The joint grave of Ruzha and Jakob Klopfer in Belgrade provides a particularly striking example, in which sculptor Toma Rosandić depicts the couple in three dimensions, head and shoulders, eternally locked in a passionate embrace.

Who, then, are these Jews? They niggled, they compromised, they rebelled as they struggled with their traditions, but in the end, each of them was buried—whether traditionally or transgressively—in a Jewish cemetery. Their homes, their shops, and many of their synagogues are gone, but their cemeteries remain.

So visit them, if you’re in the neighborhood—I think you’ll find that you have more than a little bit in common. And if ever you’re in Bucharest, give my best to poor old Adolph Hittler.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Gavriel Savit is the award-winning author of the New York Times Bestseller Anna and the Swallow Man and has performed on Broadway and stages around the world.