Mommy, What’s a Spliff?

How to keep your kids from hopping onto the magic bus

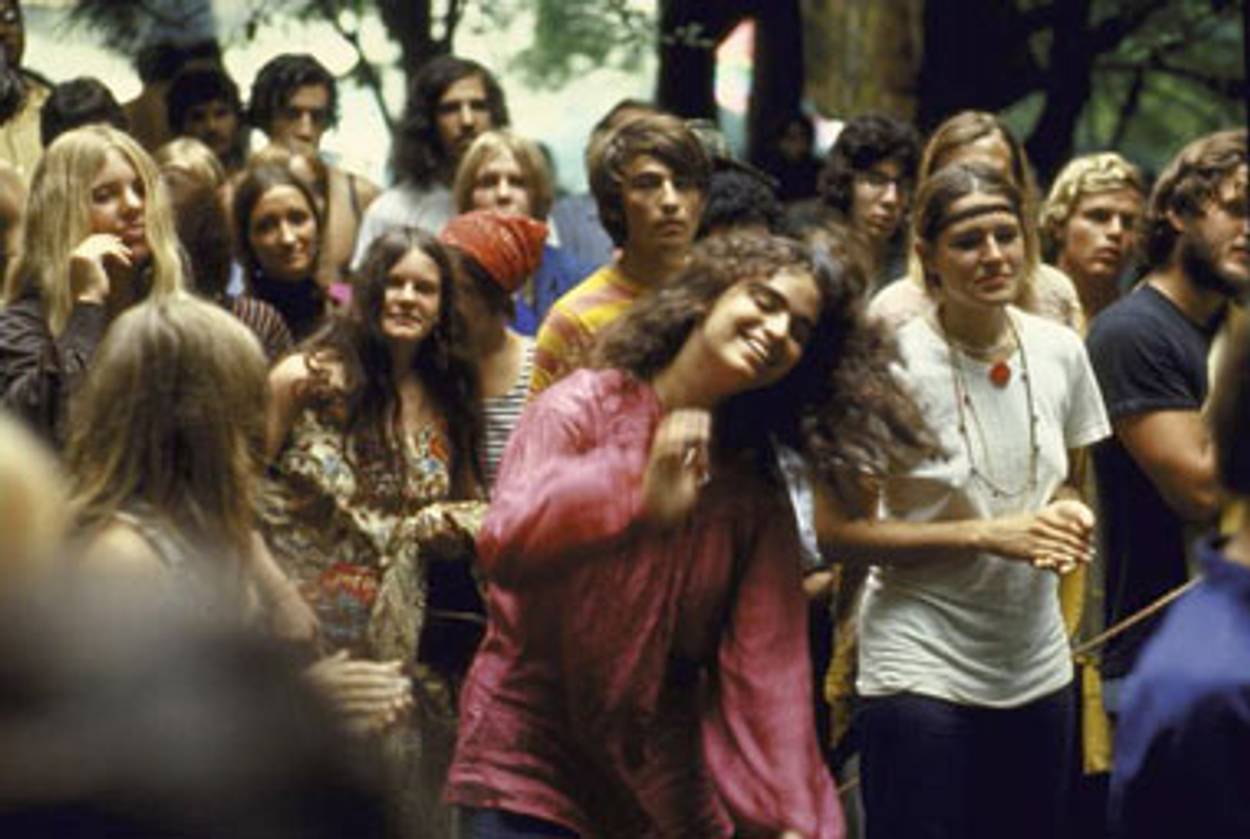

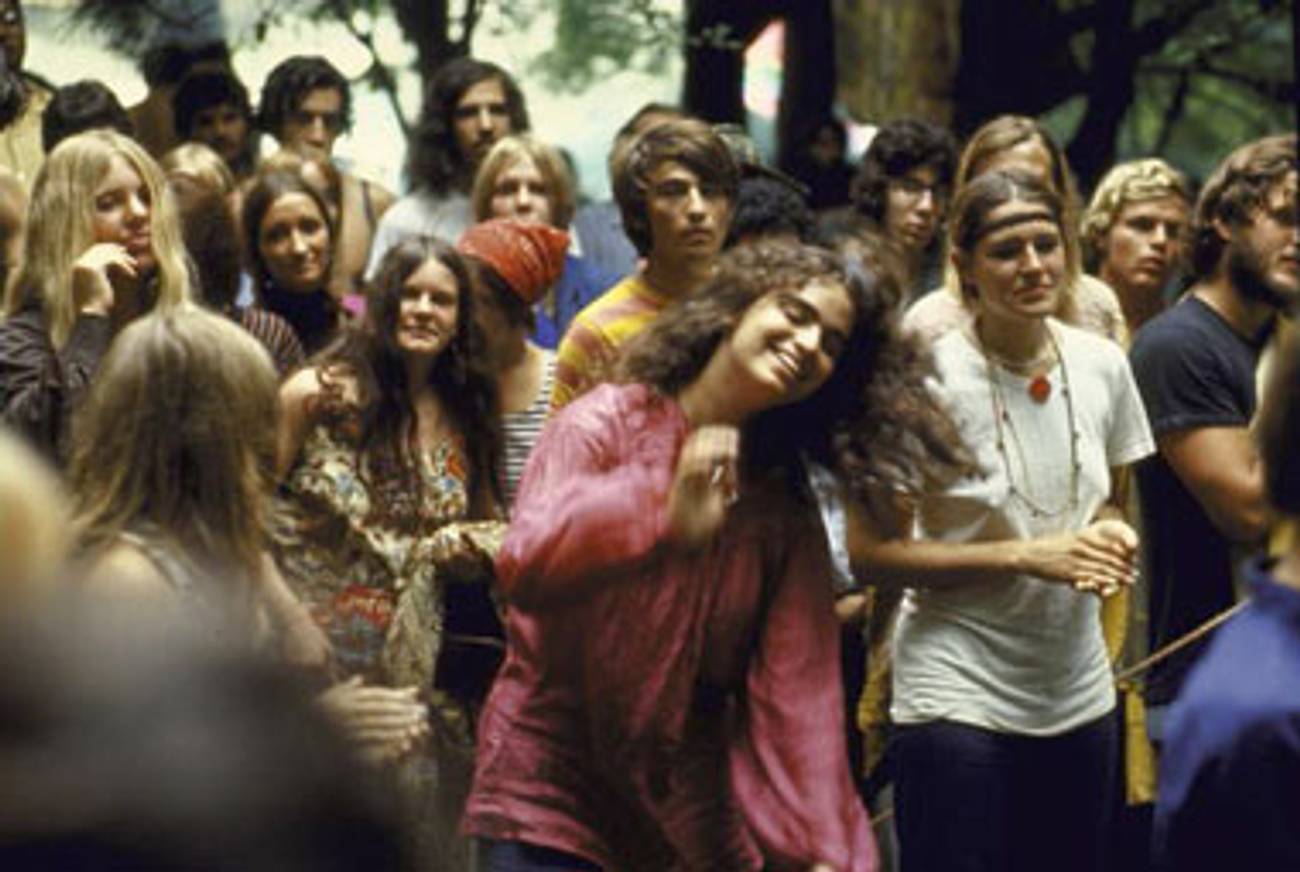

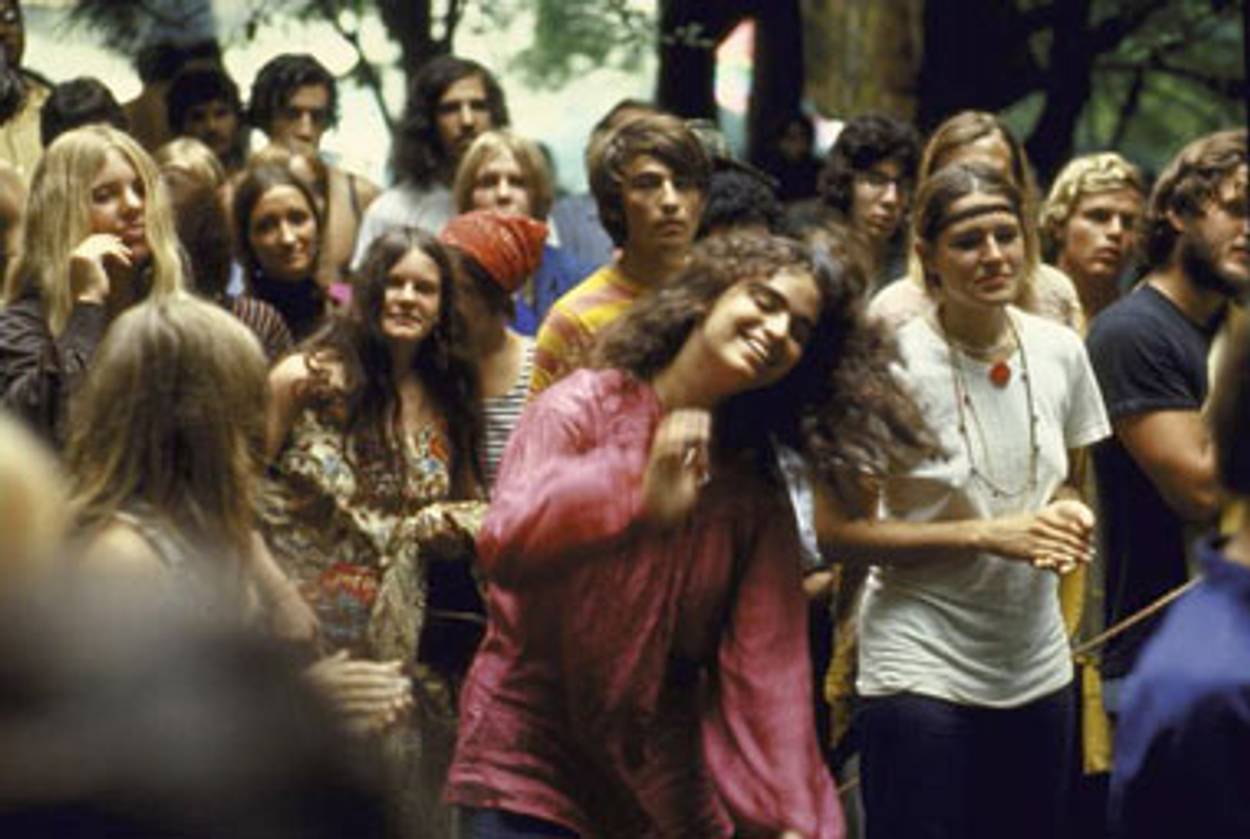

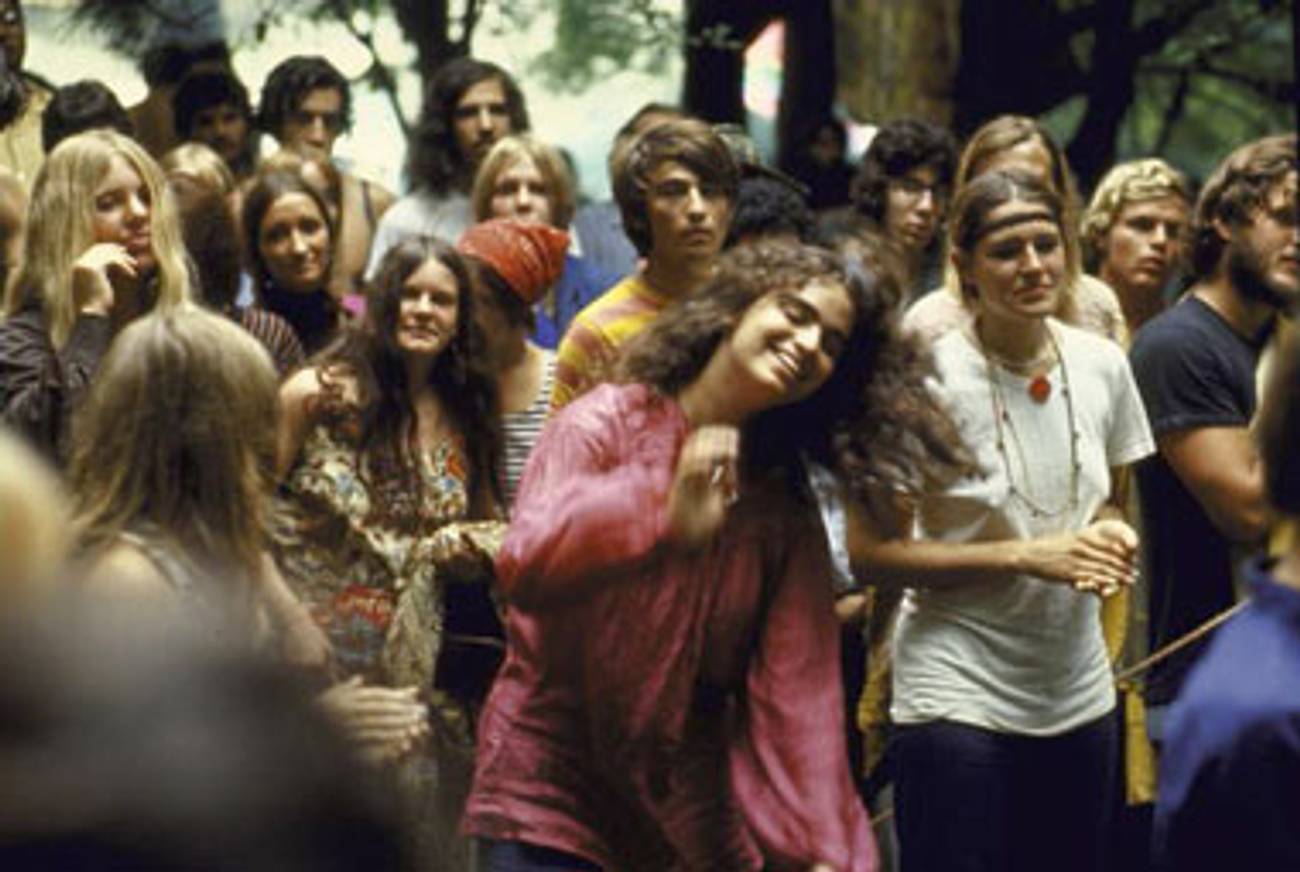

Was the world crying out for a self-published children’s book about the Woodstock Festival, minus any mention of drugs or sex, written by two married Orthodox Jews and illustrated by a visionary painter who is a ba’alat t’shuvah? Probably not. Yet the book, Max Said Yes! The Woodstock Story (Change the World Press, 2009), timed to the 40th anniversary of Woodstock this month, is oddly charming. Written by Abigail Yasgur (a cousin of Max Yasgur, who owned the farm in Bethel where the event took place) and her husband Joseph Lipner, and illustrated with artist Barbara Mendes’s hallucinatory, electric, deliciously far-out Aquarian paintings, the book celebrates Max Yasgur’s hospitality. (“He raised cows, sold milk and cheese./He liked kids with big ideas like these.”) The rhythm’s a bit forced, but the notion is sweet: a story about one farmer who opened his land to hippies when all the other farmers said no.

Was Max an observant Jew like his writer cousin? “We do not have good information on ‘how Jewish’ Max was,” Lipner told me. “But his welcoming hundreds of thousands of people onto the farm strikes me as a rather extraordinary example of the Jewish value of hachnassat orchim—welcoming guests.” Max Said Yes! isn’t an explicitly Jewish book, and it doesn’t draw an overt parallel between Max’s behavior and that of our tent-opening forefather Abraham, but the authors believe the analogy’s there. Still, is it weird to have a book about Woodstock that doesn’t mention sex or drugs at all? Lipner and Yasgur told me they’d joked around with some couplets that were left on the cutting-room floor:

In land filled with alfalfa seed

They relished LSD and weed.

They lay down in the fields and went to bed

With people to whom they were not wed

Mm, not so much. Ultimately, the authors decided that parents could use the book as a jumping-off point to talk about sex and drugs with their kids—or not. So for those of us—Woodstock Generation, Gen X, and Millennials—who did inhale, the question remains: how do we talk about drugs with our kids?

Kiki Schaffer, a social worker and director of parenting, family and early childhood at the 14th Street Y in Manhattan, laughs: “This subject is to parents of teens what sleep is to parents of newborns.” In other words: it’s the biggie, the giant bong in the room. Schaffer’s strategy is to plant the seed (as it were) early. “I tell younger kids, ‘Think about what we put in our body,’” she says. “Would you put worms in there?’” Schaffer believes that early education about drugs and alcohol is about encouraging kids to think about choices and self-regulation, so that when they grow older, they’ll continue to question what they ingest. As they reach preteen and teen years, she says, “Parents can start saying, ‘There are a lot of things we once didn’t think were harmful but studies have since shown they were: cigarettes, medications women were given in pregnancy.” Like many experts, Schaffer is not a fan of “Just Say No” education. “I hate it,” she says. “It doesn’t engage the hearts and minds of children or empower them to make good decisions—real life is about learning to be a decision-maker.” Indeed, those of us who grew up with Reefer Madness-style education learned only to laugh at parental paranoia.

Julie Holland, an assistant professor of psychiatry at NYU School of Medicine and author of the forthcoming Weekends at Bellevue: Nine Years on the Night Shift at the Psych ER (Bantam, October 2009), agrees that the “Just Say No” approach is misguided. For one thing, she says, recent studies indicate that marijuana isn’t a gateway drug—hysterically insisting to your kids that one toke is a fast track to Cobainville makes you look like an untrustworthy doofus. In 2008, 43 percent of 12th graders reported trying marijuana once or more—clearly they haven’t all become raving, heroin-shooting, paint-huffing street addicts. A better strategy, Holland says, is to stress the potential consequences of doing something illegal. “Many schools have random drug tests,” she says, “and if you test positive, you can’t do sports. If you’re a senior, you could lose your student loans.” Explaining how drugs affect developing brains is also vital, she continues. “Because the adolescent brain is still in a formulation stage—pathways are getting laid down, connections are being made—in a perfect world kids wouldn’t use any substances, including alcohol. But in the real world, statistics show that’s unlikely.”

Holland stresses that parents should be as concerned about legal drugs (cigarettes, alcohol, and prescription drugs) as about street drugs. Unlike the kids at Woodstock, kids today rarely experiment with acid. Today, the big drug of choice is “pharmies.”

“Excuse me?” I say, like the old fart I am.

“‘Pharmies’ are what kids today call prescription drugs,” Holland explains. “So keep track of what’s in your medicine cabinet—especially all you neurotic Jews taking benzodiazepines [Xanax, Valium] so you can sleep.” Other modern-kid faves include narcotic pain killers (Vicodin, Percocet, Oxycontin), ADHD drugs (some kids resell them as weight-loss aids), steroids, and the cough suppressant dextromethorphan (which the kids call “Robo”). Not to harsh your mellow or anything.

So, my fellow post-Woodstockians, what should we do? There are terrific online models of nuanced, non-scare-tactic-y speeches to give to teenagers. With my own kids (now seven and four), my inclination is to wait until they start asking questions. But I also don’t want to end up in the same situation as my mom, when she tried to give me the sex-ed talk long after that particular train had left the station. So in a couple of years, I think I’ll sit Josie down and say, “You may start having kids offering you drugs to feel good—pills, things to drink, things to sniff, and things to smoke. My hope is that you’ll talk to me about it. Just because something is legal doesn’t mean it’s safe. You don’t know who got what where. And if you ever get in a situation where you feel unsafe or out of control, know that you can call me or text me and I will help you or get you, no questions asked and no punishment given.”

And what if Josie or Maxie ask about Mommy’s drug history? Well, I’ll tell the truth. (And no, I’m not telling you.) And we’ll continue to share a regular sip of Shabbat wine. One recent study found that kids who drank with their parents were less prone to binge drinking. Thus in the spirit of Woodstock, I offer my own conclusion:

Your kids’ addiction you will head off

If you think of Max, and share a quaff.

Treat your kids like sensate beings.

And they’ll grow into responsible teens.

Or so I hope.

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.