My great-grandmother Sarah Feinstein was murdered on Aug. 1, 1913, in Winnipeg’s “Hebrew Colony.” The city’s only unsolved homicide that year, it made the Canadian newspapers from Toronto to Vancouver, in English and Yiddish. The Winnipeg Tribune called it “without doubt one of the most mysterious occurrences ever recorded in the annals of this city.”

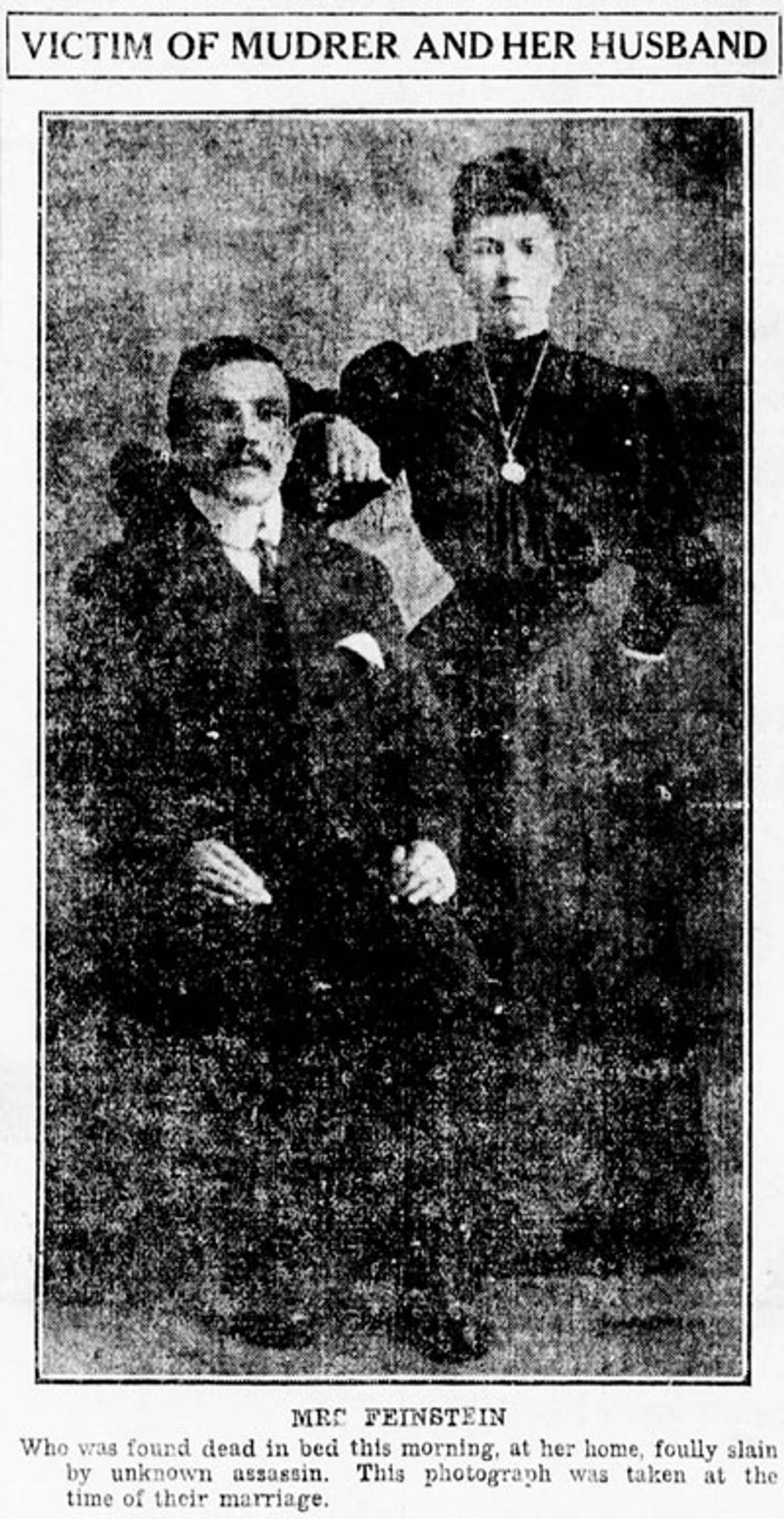

From the ‘Winnipeg Tribune,’ Aug. 1, 1913 (Courtesy the author)

A century later, when I set out to investigate this piece of my family’s history for a book I am writing about the murder, I knew almost nothing about my great-grandmother. I had just one photograph of her, taken on her wedding day. She is standing tall, stern-faced, her hair swept up, pendants hanging from her necklaces, her elbow resting on the back of a chair.

While I didn’t think much about it at first, this was also the only photograph I had of my great-grandfather David Feinstein, sitting in that chair with a trim mustache and neatly parted hair, wearing a stiff-collared shirt under a jacket and tie.

Sarah was just 26 when she was killed. Although she’d had a relatively full life in the seven years since she’d immigrated to Canada from Russia—she’d gotten married and had four children—her story was cut dramatically short by her assassin, leaving precious little of her for me to discover; there were no more photographs to find.

But David lived almost six more decades after the murder, finally dying of a stroke in 1971, a few months after I was born. So what began as an investigation into my great-grandmother’s death soon turned into an investigation into my great-grandfather’s life, years of research that revealed many more photographs, and tales I’d never heard, and relatives I’d never met. The things I learned about him as I collected these images and stories changed how I thought about not just my own family history, but the story of Jewish immigrants more broadly—a story that I thought I already knew.

I traveled from New York to Winnipeg, where I talked to historians and archivists, visited old houses and cemeteries, and pored over census reports and official documents. Immigrants from Russia, my great-grandparents lived in a modest wooden house in Winnipeg’s crowded North End, then a largely Jewish neighborhood known as the Hebrew Colony, or New Jerusalem. I could picture the area in those days, imagining it to be a sort of miniature Lower East Side—streetcars, Yiddish theaters, kosher butchers, small synagogues. My great-grandparents, I thought, were Yiddish-speaking urbanites living in a largely Jewish neighborhood filled with recent immigrants, scrambling to get by in tiny, crowded homes. I’ve spent time on the Lower East Side, I’ve visited the neighborhood’s Tenement Museum; I could imagine what their lives were like.

But as I dug deeper into the murder and its aftermath, learning more about my great-grandfather, I realized his life might have looked quite different from what I’d expected of a newly arrived Jewish immigrant in the early 1900s.

When Sarah was murdered, David was hundreds of miles away on business, in Canora, Saskatchewan. It was there that he received a telegram telling him his wife had been murdered, and he should return home at once. The 300-mile journey took more than 12 hours on the Canadian Northern Railway, whose acronym gave the recently incorporated town of Canora its name.

What was he doing there, I wondered? I’d never heard stories about Saskatchewan before. So when I located a few distant cousins in Winnipeg—people I’d never heard of, much less met, before I started doing research—I asked them if they knew anything about the family’s connection to Saskatchewan. They shared photographs and stories I didn’t know—about horses and cattle, liquor and gambling, organized crime and life on the prairie. The more I learned about my family, the more I realized that I’d only learned half the story in Winnipeg.

Saskatchewan, it turns out, wasn’t just a place my great-grandfather went on business. It was a key part of our family’s forgotten story—and a place that held a different kind of Jewish history for thousands of people, far from the big city’s crowded Hebrew Colony. And my great-grandfather wasn’t just an urban immigrant scratching out a living in a tiny house in the city; he was a cowboy, riding horses out on the Canadian prairies.

The first Jews arrived in Canora when the hamlet was founded in 1905, shortly after the railroad tracks were laid in 1904. Residential lots sold for as little as $150; ads for the Canora Townsite Company, which handled the sales, touted the town as “the future railroad and agricultural center of eastern Saskatchewan”—the province having been established in 1905 as well.

Lured by cheap land and job opportunities, recent Jewish immigrants from Russia arrived at other nearby small towns around the same time; my great-grandmother’s brother-in-law, for example, opened a small grocery in Sturgis, Saskatchewan, 25 miles from Canora. Meanwhile, Jewish agricultural colonies began to grow and multiply as the Jewish Colonization Association purchased thousands of acres of land in Saskatchewan in the early 1900s—giving birth to colonies like Sonnenfeld and Edenbridge, commonly known as Yidn Bridge.

Jews quickly became a prominent part of Canora, swelling to 10 percent of the population within a few years. Samuel Korbin arrived in 1905 and opened a general store; when the town was incorporated in late 1910 he served as town councilor and in 1912 he was elected mayor. Sam Cohen, whose family had been among the founders of Winnipeg’s Shaarey Zedek synagogue in 1880, opened the Canora Hotel on Main Street across from the train station. Other Jewish newcomers were butchers and shopkeepers.

My great-grandfather and his brothers arrived in 1908. They farmed three-and-a-half miles northwest of Canora, and started a business as cattle dealers. They also owned horses: One of my newfound cousins in Winnipeg told me the brothers were “expert horsemen.” They had once been “true cowboys,” said another cousin, noting that they used to break wild horses and sell them to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. These stories were quite different from my mother’s memories of her “Zayde Dovid” from his later years as a Yiddish-speaking, synagogue-going, bespectacled and cane-carrying grandpa.

David’s brother Harry bought a house in Canora; the other brothers, who all had homes in Winnipeg, would stay with Harry when they came on business. That’s where David was staying when he got the telegram that his wife was dead.

But this wasn’t the end of David’s time in Saskatchewan, as I soon discovered. Two years after the murder, he married a second time, and in 1916, the whole family moved to Canora full-time so David could be closer to the livestock that provided his livelihood. They stayed for more than seven years.

Canora still had fewer than a thousand people in 1916, but it was surprisingly diverse, populated almost entirely by recent immigrants: Chinese waiters and laundrymen, Irish dressmakers and postal workers, German stenographers and carpenters, and Scottish veterinarians and police officers. Alongside the Jews lived Methodists, Catholics, Anglicans, and a large number of Doukhobors—radical Christian pacifists from Russia, several thousand of whom had settled on communes in western Canada after 1900.

By 1921, more than 13 percent of Canora’s 1,200 residents were Jewish. The community of nearly 200—representing some 30 families—started a synagogue, hired a Jewish teacher, and opened a kosher food store. David and his second wife, Bella, stayed in Canora long enough to witness the growth of the Jewish community; their two youngest children were born there as well.

David’s stay in Canora coincided with Canadian, and later American, Prohibition. According to a few of my cousins, some of the Feinstein brothers—possibly including my great-grandfather—were probably involved in bootlegging. There was more than just horses in those barns, one suggested; perhaps the family’s connection to organized crime had something to do with the murder? It did explain one odd thing I’d found in my research: While the brothers were dealing cattle in Saskatchewan, according to a business directory, they were also officers of a short-lived company in Winnipeg called Manitoba Vinegar Manufacturing.

The notion that the brothers might have been involved in unsavory endeavors was bolstered by other stories I learned, about how they were serious gamblers, and tax cheats; two of my great-grandfather’s brothers were later fined in what the Tribune called “Canada’s biggest tax evasion case.”

As the Jewish population of Canora started a dramatic decline in the 1920s, leading up to the Great Depression—foreshadowing a trend for Saskatchewan’s Jewish community as a whole, which saw its numbers peak at 5,000 in 1931 and plummet to less than half that today—David’s family returned to Winnipeg. He bought a house on Mountain Avenue in the North End. This is the place my grandmother Ethel, a teenager at the time, would later describe as her childhood home, starting her life story in Winnipeg’s Hebrew Colony; she never told her children or grandchildren that she’d spent half her childhood in Saskatchewan. The family’s history there was forgotten, just as the larger Jewish community’s history there has been largely overlooked.

I arrived in Canora, in the heart of what is now known as “Good Spirit Country,” on the last day of May 2017, to learn more about my family, and the area’s Jewish history. I was greeted by Lesia, a 15-foot-high statue of a woman in traditional Ukrainian dress standing at the side of Route 9, holding a loaf of braided bread and a shaker of salt on a tray draped in fabric.

My great-grandfather would never have seen her. Lesia was erected in 1980 as a tribute to the town’s Ukrainian community, who counted among the region’s first settlers and remain a major demographic group today among Canora’s 2,000 residents—none of whom are Jewish, according to the most recent census.

I turned up Main Street, which was decorated with maple leaf flags in honor of the upcoming celebration of 150 years of Canadian independence: Here, in a month’s time, a festival would feature jugglers, magicians, a petting zoo, and bands playing everything from rock to country to Ukrainian music. I saw just one familiar chain store: Tim Hortons, Canada’s ubiquitous doughnut shop. There was a pizza parlor, a dollar store, a local bank, as might be found in any small town. But I also saw places that only made sense in Canora: the outdoor ice cream stand that serves poutine, the Chinese restaurant that advertises its chili and pierogies in the window, the Ukrainian Heritage Museum.

At the end of Main Street, I parked in front of the Canora Hotel, which Sam Cohen had opened a century earlier. This was a prominent building—a three-story brick block that today comprises eight guest rooms over a bar and restaurant—that my relatives would surely have known well. They would have arrived in Canora not by road, but by train, and as they exited the station, the first building they would have seen was this hotel, across Railway Avenue. A hundred years ago, my great-grandfather and his brothers might have stopped for a drink in the street-level bar. Now, this was where I’d be staying.

Unlike my earlier research trip to Winnipeg, in Canora I had no old houses, no graves, no synagogues to visit, and no relatives, however distant, to meet. I didn’t think I’d find anything specific to connect this place to my family’s history.

Canora does have a museum of local history, however, housed across from the hotel in the small train station. Canora has the country’s oldest Class 3 railway station still in operation, built in 1904 for $5,000. These days the VIA Rail trains only run twice a week to Winnipeg; the trip takes eight-and-a-half hours each way—a long ride, but shorter than the one my great-grandfather took back in 1913 when he learned of his wife’s death.

As I walked through the CN Station House Museum, I saw several exhibits on display: an eight-foot-tall Orange Crush bottle that was used to promote the brand’s new clear soda bottles in the 1950s, souvenir golf shirts and DVDs, and a poster touting Canora for winning a competition for the best-tasting municipal water in Canada. More along the lines of what I’d expected, there were train-related artifacts from the past hundred years. A quilt made during WWI commemorated the area’s early homesteaders, and historic photos of the town, where the Canora Hotel is readily recognizable, hung on the wall.

The museum was filled with curiosities that helped me understand Canora in a broad sense, but there wasn’t much that connected me to my family’s specific history—not the quilt, or the giant soda bottle, or the delicious tap water. And then I saw a small item on display that seemed quite old: the train station’s original telegraph.

I’d found a piece of my history. It was this very machine that transmitted the message to my great-grandfather back in 1913, telling him that his wife was dead, and he needed to return to Winnipeg at once.

It was just past noon on a Friday when he got the message. I imagine he was returning to town after spending the morning on the family farm. Distraught, he probably packed a suitcase as quickly as he could before heading back up Main Street, past the Canora Hotel, to this very station. The next train to Winnipeg wasn’t leaving until 4:55, so he had time for the news to sink in. Maybe he had a drink at the bar across the street. Maybe he sat silently for hours on a bench on the platform, or asked the telegraph operator to send a message back to Winnipeg to say he was on his way. Or maybe, while he waited to begin his long journey home, he stood in front of the station, staring down Main Street at this remote prairie town where one chapter of his life had just come to an abrupt end—and another unlikely chapter of his life as a Jewish cowboy would begin a few years later.

I haven’t found any photos of David in Saskatchewan. But now that I’ve visited the town he once called home, I can create a mental image of my own, a picture of my great-grandfather and his brothers—cowboys, gamblers, bootleggers, and cattlemen—on the prairie. It’s not how I used to picture my Jewish ancestors. But it’s one of the ways I think of them now.