My Last Veteran

Saying goodbye to the soldiers who fought in WWII

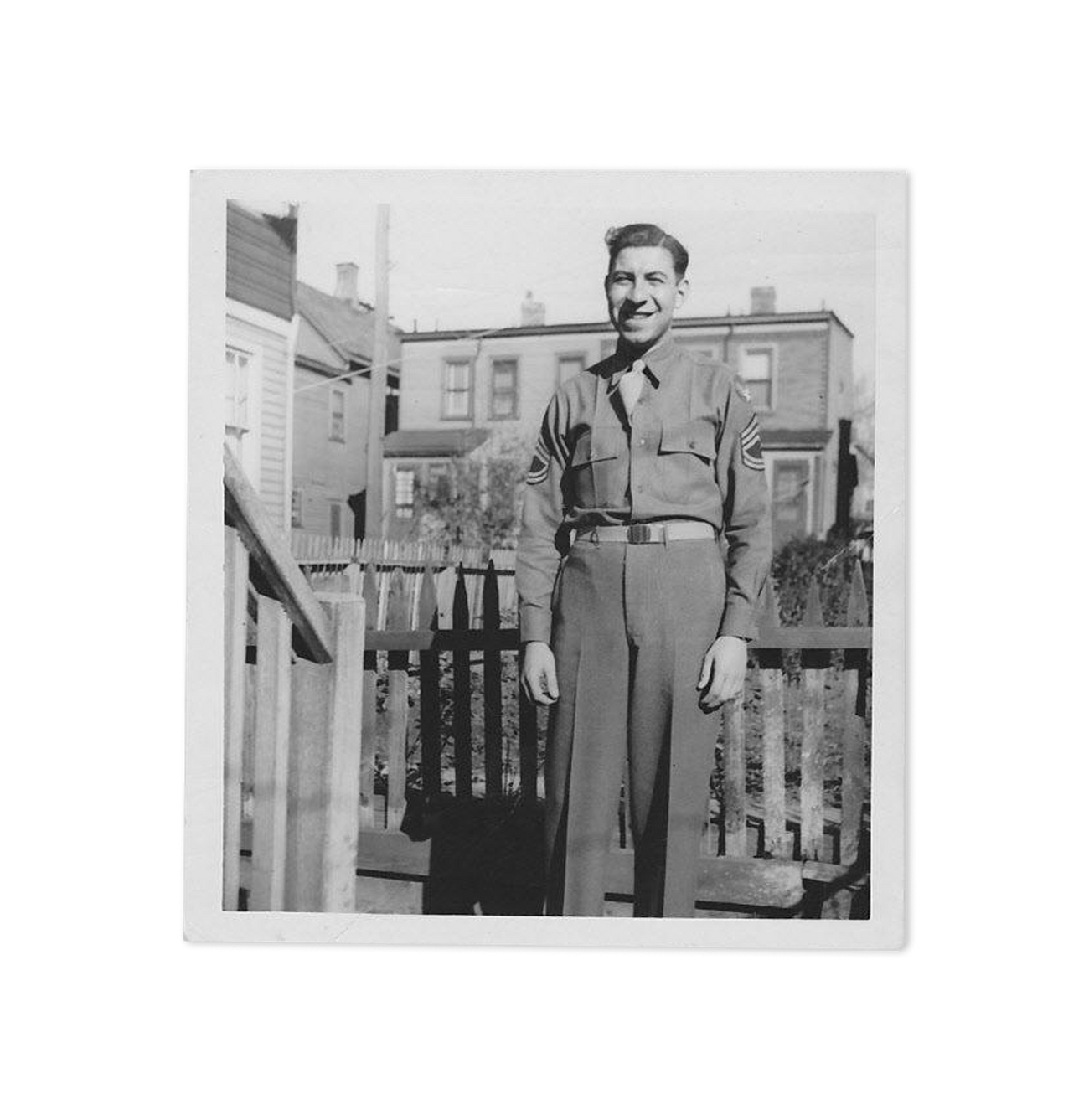

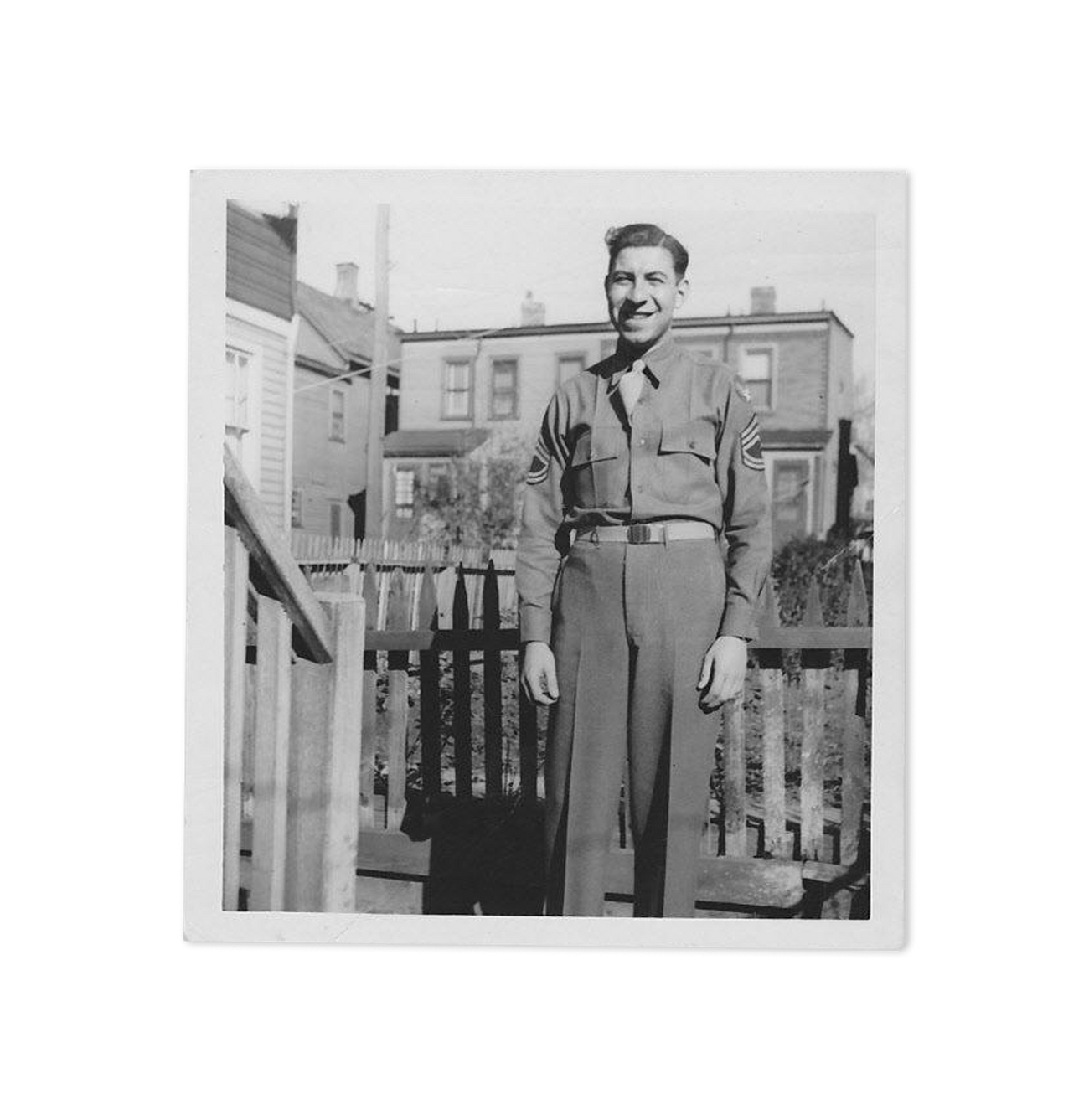

I became a fan of WWII combat veteran Isadore “Izz” Kozatch seven years ago, within minutes of our first meeting at his home in Denver. Maybe it was because he displayed that Jewish tough-but-funny persona that reminded me of my late father, who was also a WWII veteran. Maybe it was because he was unafraid to admit that he had been afraid—as flight navigator of a crew that had conducted 35 bombing missions over Europe—while asserting that he still “slept like a baby.” And maybe because he was unafraid to deliver his opinions on topics ranging from why the U.S. had won the war (“we out-produced the enemy”) to the negligible role of the bombardier (“a chimp could open the bomb bay doors”).

And then there was the way he immediately apologized after using a familiar profanity to relate his retort to a pilot who had been “on him.”

“Sorry, I know you’re a religious woman” he said, referring to my traditionally observant Jewish lifestyle.

But I was more charmed than offended. Izz was the last of the 15 American Jewish WWII veterans I interviewed for the Veterans History Project of the Library of Congress, and his free-range style of storytelling had me alternately laughing and saying, “wow.” As he walked me to my car, he gave me what I considered to be the ultimate mid-20th-century compliment: “Your husband is a lucky man.”

So when Izz’s daughter emailed to tell me of her father’s death on April 19 at age 99, the finality hit me. My vets, as I called them, were now all gone.

When I first began interviewing American Jewish WWII veterans in 2006, beginning with my late beloved father, Louis Brown, my not-so-secret mission was to learn how this war had shaped their lives and bifurcated identities, and to do my small part to ensure that even after their cohort of 550,000 American Jews—out of the 16 million Americans who served in WWII— all disappear from the earth, at least some of their stories would remain.

And that people would know that Jews “weren’t just clerks or typists in the war,” as Izz said, in explaining why he joined the Jewish War Veterans organization 60 years after the war. “I wanted to make a statement,” he told me.

Still, despite dealing with the antisemitic tropes of their time and in the military, neither Izz nor the others had known about the extent of the Holocaust until after the war. They also kept their own wartime experiences mostly to themselves. Like others in their generation, “they went home and lived their lives,” as actor Mark Rylance said of his grandfather, in the recent PBS series My Grandfather’s War.

But as old men, my vets were finally ready to talk, especially to a stranger who was also a member of the tribe. Along with their stories, most of which I donated to the VHP, a few gave me their memoirs and some of their memorabilia.

There were times, while interviewing this diverse group of men in Colorado, Delaware, Maryland, New York, and Washington, D.C., that I wished I could have gathered them at the WWII Memorial, or better yet, in a room at a JCC or Y somewhere, for a once-in-a-lifetime Memorial Day brunch. I envisioned arranging a table with bagels and lox and Danish pastries, like at the Sunday morning JWV meetings I attended. And maybe even throwing in some whitefish salad.

I would have the former flyboys in one corner: navigator Izz; Harry the bombardier, who had gone on 40 missions over Germany, France, and Italy; and Harold, the pilot who flew missions during D-Day. In another corner, I’d put David and Al, who both fought in the Battle of the Bulge and against antisemitism in the military. I’d put the two Jeromes, one a concentration camp liberator, the other in Army intelligence, together with German POW interrogator Seymour, or Sy, who had arrested German commander Alfred Jodl and hung out with Eisenhower’s girlfriend Kay Summersby. And finally, I’d get the guys who were in the Pacific Theater together at their own table, including my dad, Louis, and Harvey, who were both on Guam; Leonard, the proud Seabee; Bernie the Navy lieutenant who remediated battleships for Japan; Irving the medic; and Herman, a battle-scarred Army Signal Corps operator who had served in the “hellhole of Okinawa.”

I’d ask Murray, a career military man and decorated first lieutenant, who eventually rose to major, to take charge of the discussion—because of his deep don’t-mess-with-me voice, because he’d landed on Normandy Beach and seen the carnage as it was depicted in the movie Saving Private Ryan, and because, as he told me, “I always took care of my men.”

There would be arguments, no doubt, between Izz and Harry on the role of bombardiers, between those who had “seen action” and those who had been spared, and whether, as Irving lamented, the guys who had been in the Pacific didn’t get as much credit as those who had served in Europe. But I would hope that there would also be some joking and schmoozing and agreeing to disagree on the value of attending JWV meetings.

Listening in on their tales of chutzpah and bravado, while probably filling coffee cups, I would hope to get further insight into how these guys seemed not to have been defeated by childhood poverty and trauma, war and postwar nightmares, family difficulties and deaths (Irving’s mother died while he was carrying the wounded in the Pacific), or the effort of having to prove themselves as Jews.

Resilience was one thing, but I also believed that these vets may have been one step ahead of other generations in finding meaning in their lives—in the sense that psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl asserted in his groundbreaking book Man’s Search for Meaning. Helping to stop Hitler from taking over the world and wiping out their people seemed to me to be a damn good legacy for boys named Irving and Seymour and Isadore.

Izz told me that he didn’t like the “greatest generation” label, though. “I don’t buy into that,” he said.

But, with apologies to Izz and the others, I do—not least for helping to make my life and my children’s lives possible.

Fifteen years ago, when I started this project with my father in mind, I expected to feel gratitude, admiration, and even awe when recording the stories of other American Jewish fathers, grandfathers, uncles, and cousins who had made it through WWII. What I didn’t expect was that I would end up loving and even mourning them. And wishing that we could have had that Memorial Day brunch.

Marla Brown Fogelman is a freelance writer in New York City. Her work has appeared in The Washington Post, Parents, The Forward, Moment, and other national and regional publications.