What’s in a Name

The legacy of Nazi laws can still be found in the official documents for our grandfather—and other Jews who had their names changed against their will

Our grandfather, the second son of a kosher butcher, came into the world late in the 19th century in the becastled river town of Wertheim, Germany. We called him our “Opa,” but his name was Felix Müller. At least we think that was his name. It might actually be Felix Israel Müller. We’re not sure.

This is the story of his name, the names of tens of thousands of other German Jews, and the persistence of the potent traces of Nazi law.

It’s not difficult to find an ancestor’s birth record in a German town if you know the year. You go to the archive holding the town’s Bürger-Bücher, or “Books of Townspeople”—bound volumes registering births, marriages, and deaths. You ask for the book corresponding to your ancestor’s birth year and flip the pages of babies until you reach your ancestor. The births appear sequentially, each new arrival on its own page.

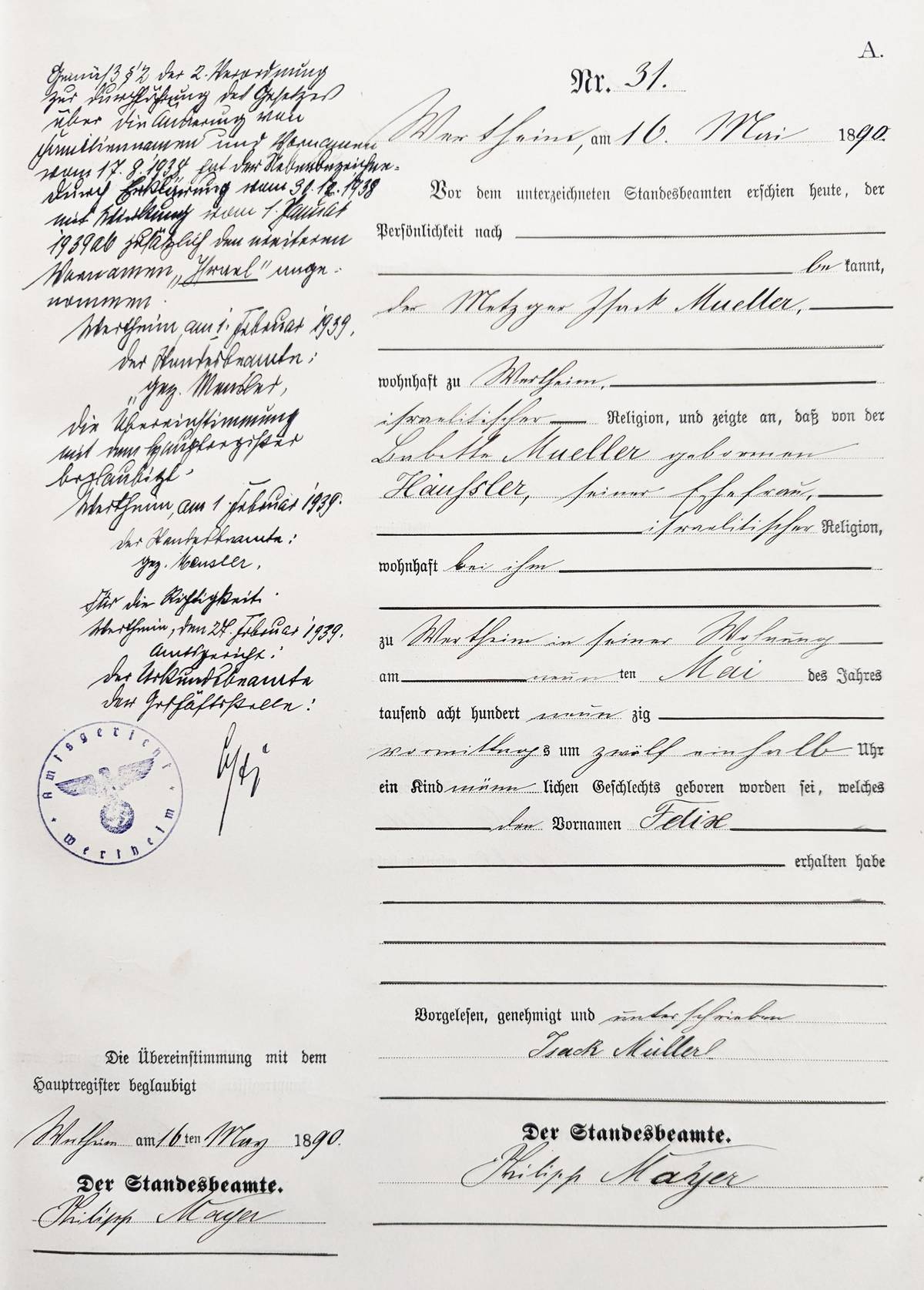

Our Opa’s page is number 31 for the year 1890. A town clerk attested to the following, filling in spaces with details: Isack Müller of Wertheim, butcher and of the “israelitische” faith, personally appeared before him on May 16 to report that a male child with the first name Felix had been born to his wife Babette Müller, née Häusler, also “israelitisch,” on May 9 at 12:30 in the afternoon at their residence.

There are similar entries in other volumes for Felix’s older brother Leopold Friedrich (born Feb. 5, 1889), sister Regina (May 21, 1899), and another sister, Hedwig, who died in infancy.

Though odd to our eyes today, the notations of religion on these pages were unremarkable in the moment, filled-in blanks on a preprinted form. The faith of every new Wertheim parent was recorded, whether Protestant, Catholic, or Jewish. It was nothing nefarious. At least not at the time.

Our Opa and his siblings grew up in a storybook town. Tracing its roots to the eighth century, Wertheim sits at the strategic spot where the Tauber River branches off from the Main, just beneath the crest of a hill the family of the counts of Wertheim deemed perfect for a castle early in the 12th century. Gabled, half-timbered houses crowd the edges of a small market square.

Felix and his siblings lived above their father’s butcher shop at the corner of the Maingasse (Main Street, named for the river) and the Judengasse (Jews’ Alley), possibly so named because it led to the town’s synagogue. This was the synagogue’s third location in town. The prior building was leveled in 1447 to make way for a church; the community destroyed the one before that in 1349 during the Black Death.

Yes, 1349: The Jewish community of Wertheim was old. There are mentions of Jews in Wertheim as early as the 11th century. A gravestone in the Jewish cemetery outside the city wall has been dated to 1405. By the early 20th century, when Felix became a bar mitzvah, a community of some 200 Jews prayed in the synagogue and dined on kosher meat from Isack’s butcher shop.

Our Opa excelled at Wertheim’s high school, earning a seat at vaunted Heidelberg University to study classics, Latin, and ancient Greek. Upon graduation he returned to his hometown for a probationary year as a teacher at his old high school. All career plans were shelved, however, as Germany went to war in 1914. Felix and brother Leopold both joined the kaiser’s army. Leopold quickly suffered a rifle blast to his arm; it would hang useless for the rest of his life. Felix served through war’s end, miraculously emerging unharmed just in time to return home to join Leopold and sister Regina in burying their mother, Babette, dead at 51, probably a victim of the Spanish flu.

Death records, like those for birth, included the decedent’s religion, so Babette was noted as leaving the world just as she had entered it: “israelitisch.”

The 19th-century bureaucrats who devised these records didn’t so much include religion as retain it. The recording of births, marriages, and deaths was sacred rather than secular business well into the 1800s. Churches and synagogues kept track of their congregants in their own records, supplying information to secular officials upon request. When cities and towns took over the task, they simply continued the existing practice.

Wertheim’s city records rest in an archive on the grounds of Kloster Bronnbach, a beautiful church and monastery dating to the early 13th century a few kilometers from the city walls. The Bürger-Buch for 1890 with our Opa’s birth record is, in the context of the collection, a recent acquisition. We focused on our family’s records during a brief visit, but with more time we might have asked to see, for example, a promissory note from 1303 in which King Albert directed Count Rudolph of Wertheim to collect the interest on a 100-silver-mark loan out of the property of the Jews of Wertheim, so long as the count didn’t overburden them.

In 1929, our Opa—now an established high school teacher of classical languages—married Alice Florence Weil in her home city of Freiburg im Breisgau, an event duly recorded in that city’s Bürger-Buch. Two years later, an entry appeared in the Bürger-Buch for the city of Karlsruhe recording the birth of Felix and Alice’s first child, our father, Joachim. The young family lived happily in Karlsruhe until 1933, when Adolf Hitler came to power as Germany’s chancellor and their lives began to unravel.

Felix was stripped of his teaching position in April under the government’s new “Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service,” which removed Jews from the civil service. After a short time he regained the job under an exemption for Jews who had fought at the front for Germany in WWI, but that lasted only until 1935, when the Nuremberg Laws revoked the exemption, leaving him unemployed. Not just unemployed, but also quasi-stateless; the Nuremberg Laws stripped German Jews of their citizenship, shifting them to a class of “state subjects” without political rights.

By 1938, our father was ready to start school. That could not happen in Karlsruhe; throughout Germany, Jewish children were barred from the public schools. A Jewish school remained open in Frankfurt, so the family relocated there in the spring.

The fall brought terror. A gang of Hitler youth chased our father through the Frankfurt streets with a noose one day as he walked home from school. Gestapo agents arrested our grandfather on the night known as Kristallnacht and delivered him to the Buchenwald concentration camp. He came home after two weeks—20 pounds lighter, head shaved, skin covered with eczema. For a week he sat motionless in a corner, staring into space.

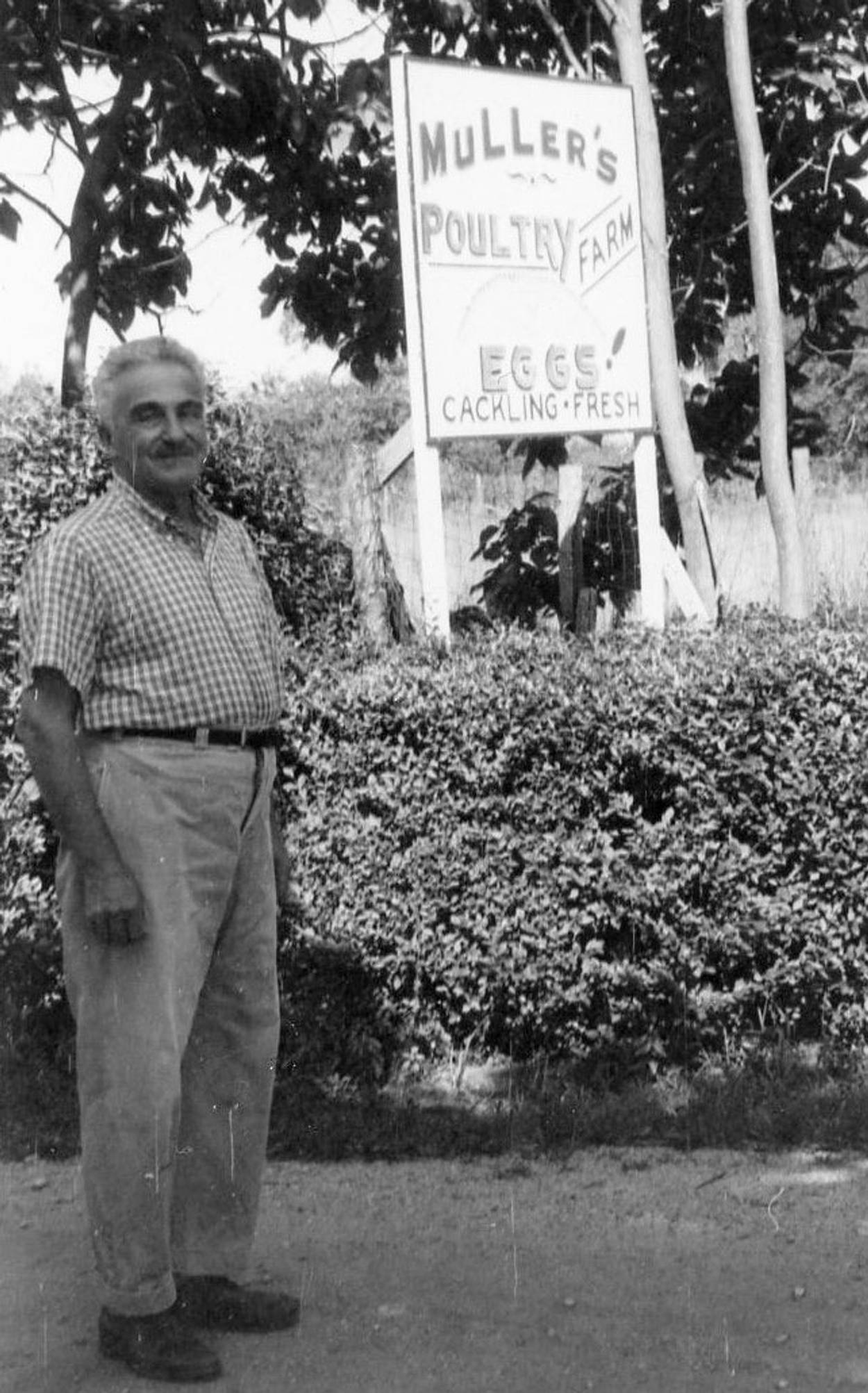

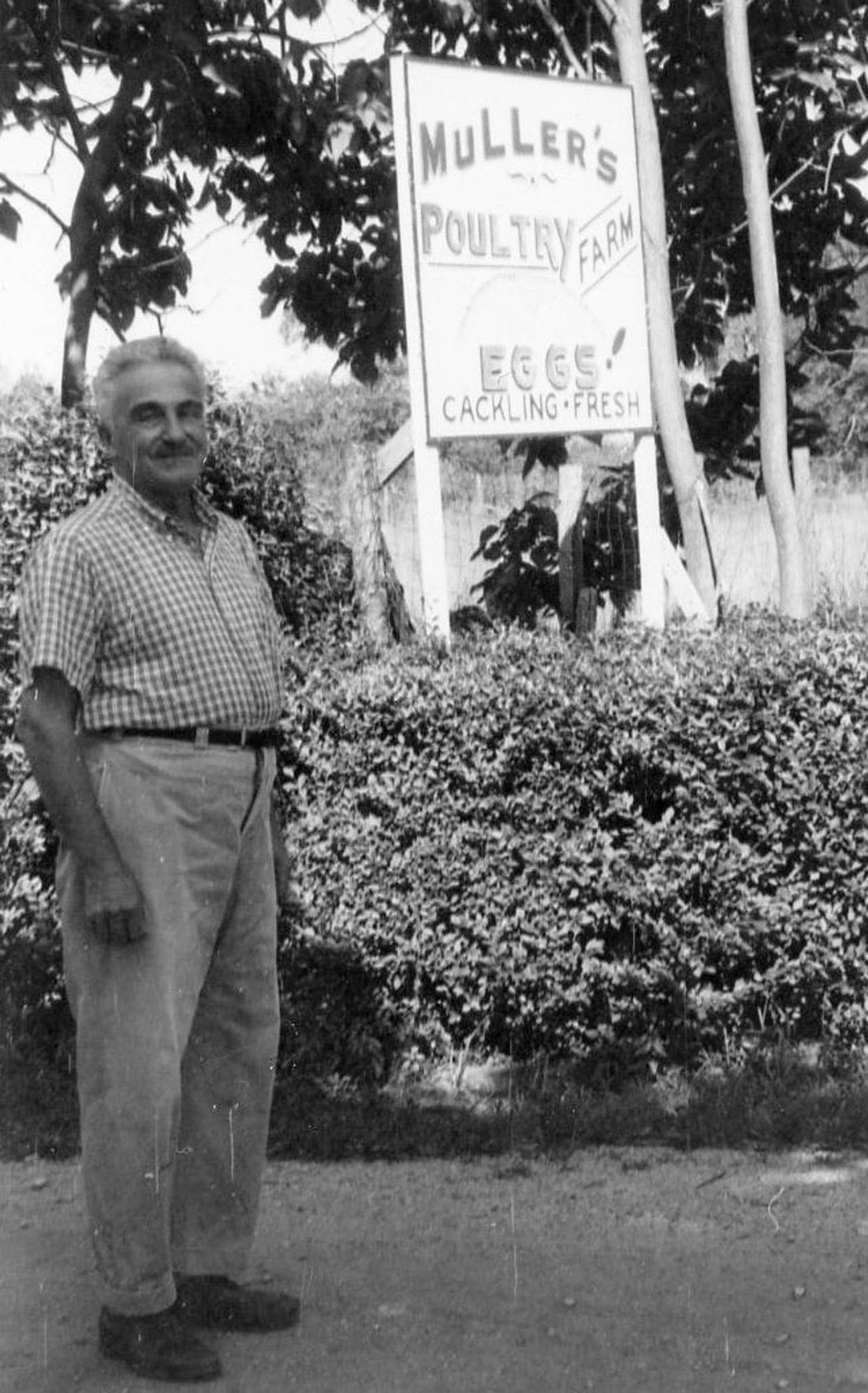

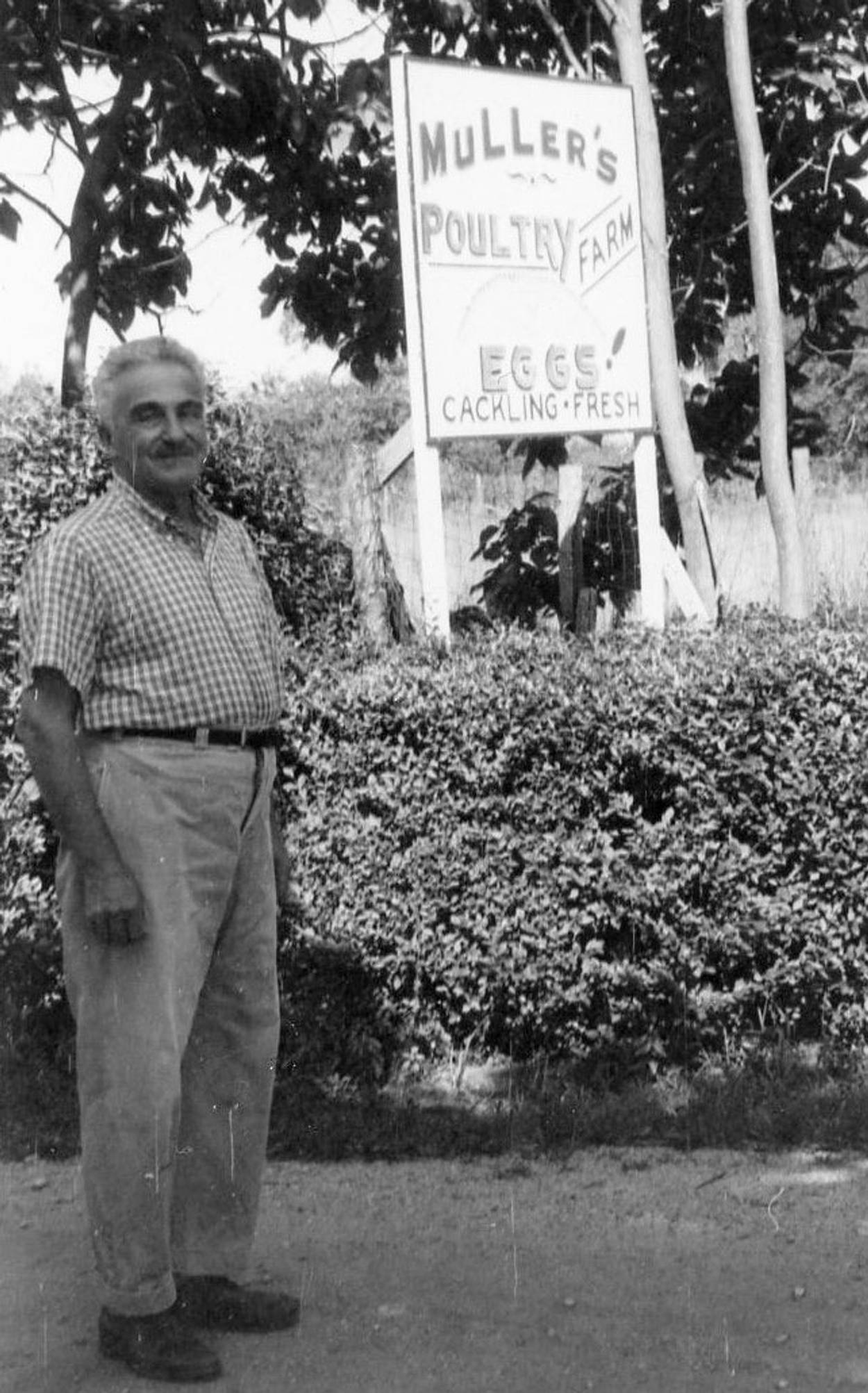

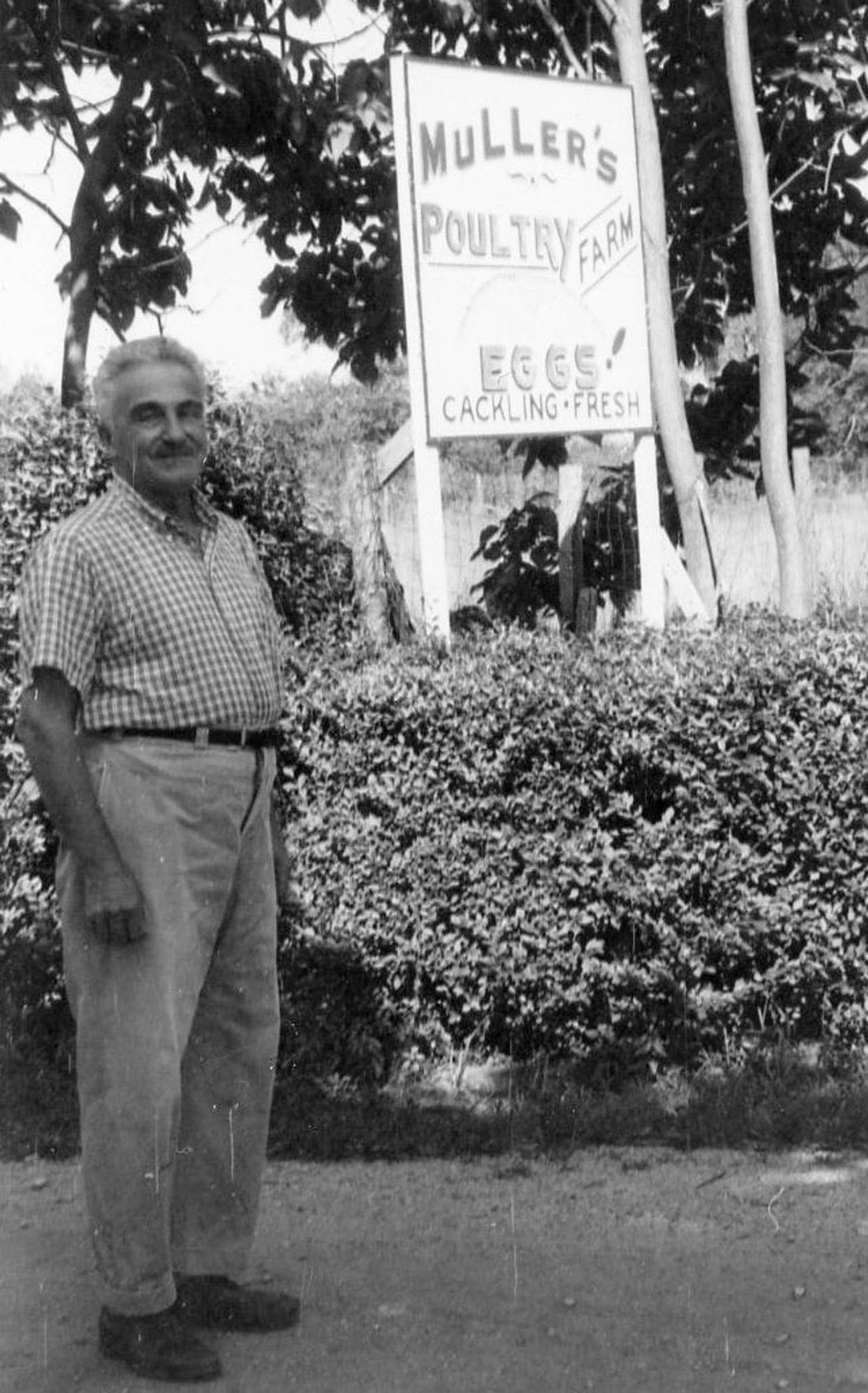

The family was able to flee to Switzerland with the help of a well-placed Swiss connection at the very end of 1938. There they spent more than two tense years waiting for a visa from any country that would take them. Finally a visa came through for the United States. Felix, Alice, Joachim (soon to become “Jim”), and little sister Beatrice arrived in New York Harbor on April 1, 1941. By year’s end they were installed on a chicken farm in southern New Jersey, out of harm’s way.

Felix’s sister Regine was also safe, having found her way to England. Leopold, however, remained in Germany with his wife, Irene. Felix and Regine’s efforts to secure them a visa failed. In April 1942 they were deported to a transit camp in the Polish town of Izbica. They were murdered either there or in the Sobibor death camp. We don’t know which. That event, alone among the family’s milestones, went unrecorded in any government register.

By the time Leopold Friedrich met his end, he had a new official middle name: Leopold Friedrich Israel Müller. Felix had the same: Felix Israel Müller. Their sister had become Regina Sara Müller.

They were far from alone: Every Jewish male in Germany was given the middle name Israel by the Nazis, and every woman Sara. This renaming was an important part of Hitler’s push to isolate and stigmatize German Jews. It came about by operation of two laws, the first being the “Law Concerning the Changing of Family Names and First Names” of Jan. 5, 1938, which authorized the interior minister unilaterally to change any name that did not comply with German law. (Names in Germany required the approval of the local civil registration office, and they still do.)

That law’s principal purpose was to lay the groundwork for a second law, enacted on Aug. 17 of the same year. This “Second Ordinance Implementing the Law Concerning the Changing of Family Names and First Names” did two things. First, it decreed that as of Jan. 1, 1939, Jewish parents could give a newborn only a name from an approved list of typically Jewish ones. There were 185 permitted names for boys (think Akiba or Isodor or Schmul) and 91 for girls (of the Chana or Hadasse or Rachel variety). Second, the law ordered that every Jewish man or woman in Germany who did not already have one of those approved names—every Leopold, every Felix, every Regina—would be branded with the new middle name “Israel” or “Sara.”

From then on, a name alone would tell “Aryans” everything they needed to know about who they were dealing with.

It took a little while for the renaming order to reach the town hall in sleepy Wertheim. On Feb. 1, 1939, an official pulled down the numerous Bürger-Bücher stretching back decades and started the tedious task of flagging the birth registration page of Jewish babies. On each, he added by hand an identical codicil in the margin implementing the name changes. The codicil was so wordy it stretched halfway down the page.

As a result of the clerk’s efforts, our grandfather’s birth record was now marred by this:

Pursuant to § 2 of the Second Ordinance Implementing the Law Concerning the Changing of Family Names and First Names, dated August 17, 1938, through a proclamation dated December 30, 1938, and effective as of January 1, 1939, the adjacent person has also taken the additional name “Israel.”

Wertheim, 1 February 1939, the Registrar: signed by Mensler

Certified in conformity with the main register, Wertheim, 1 February 1939, the Registrar: signed by Mensler

For correctness: Wertheim, 27 February 1939, clerk of the office of the district court

Beneath all of this appear the official’s initials and, in purple ink, the large official stamp of the local court. It’s a circle about the size of a half dollar featuring an eagle with wings outstretched. The eagle’s talons clutch a wreath displaying a swastika.

Leopold’s birth record was marked identically, as was Regina’s, but with “Sara” in place of “Israel.”

Germany’s 1949 constitution, drafted under watchful Allied eyes, offered restored citizenship to people stripped of it on racial, religious, or political grounds between 1933 and 1945. The law also extended this offer to those people’s descendants. The process for obtaining German citizenship through the law is daunting. Trust us; we did it. You need to submit certified proof of your own birth, citizenship, and, if applicable, marriage, as well as information about all the places you’ve ever lived. And you have to submit all of that documentation for the forebear on whose Nazi-stripped German citizenship you are basing your claim.

We based our claims on our father because he had already gotten his own German citizenship restored and had all the necessary documents on hand.

But if he had not been born in Germany, we would have had to base our claim on our grandfather. We would have had to support our applications with certified copies of our Opa’s birth record, the one last updated by a Nazi official in 1939, the one that forced on him the middle name “Israel.”

The one with the swastika.

It’s easy to see the entries in Germany’s Bürger-Bücher as traces of a dead and distant past, but they’re not. They are legal documents with enduring life and force. And those of the Jews of Wertheim (and, no doubt, some other German towns and cities) still bear the disfiguring scar of an uncorrected Nazi past.

That’s not quite true. A correction came soon after the war ended. The first act of the Allied Control Council governing occupied Germany in 1945 was to repeal a long list of Nazi laws, among them the one requiring Jews to take the names “Israel” and “Sara.” Germans took back all reins of governing power from the Control Council in 1955 and promptly rid themselves of their former occupiers’ rules. But a few of the Control Council’s actions they endorsed, including the repeal of the Nazi name-changing law.

We might wonder about the legal effects of the repeal. Obviously no Jewish baby born in Germany would ever again have to take the name Israel or Sara. (There were likely to be few such babies.) But what about all the German-born Jews alive in 1939—those who became refugees and those who perished? Did the repeal restore to them their pre-1939 names? Did Felix Israel Müller revert to Felix Müller automatically? Or did he need to file a request that a clerk in Wertheim’s town hall strike the swastika stamp and the name “Israel” from the margin of his birth registration?

Requiring Jews to go the lengths of filing requests might seem an absurd interpretation of the law’s repeal, but consider a parallel situation. When the Control Council repealed the name-changing law in 1945, it simultaneously repealed the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, including the provision stripping Jews of their German citizenship. But that repeal was never understood to restore German citizenship automatically to each person from whom it had been taken and their descendants. To bring about that change, a person had to file a formal request, as we ourselves have done.

If a postwar repeal didn’t automatically restore Jews’ citizenship, why would a postwar repeal automatically restore their names?

Indeed, some German officials held that it didn’t. In her fascinating recent book Personal Names, Hitler, and the Holocaust, scholar I.M. Nick relates the example of Frankfurt am Main, the largest city in the state of Hesse, where in 1947 administrators, citing the administrative burden, decided to strike “Israel” and “Sara” only from the records of Jews who took the initiative to ask. Surely, as one Hessian official coldly put it, the “racially persecuted” Jews, “who had to endure far greater unpleasantness,” could “take on the very small task” of filing a request, which, after all, would require a message of “only two or three lines to the Registry Office.”

What was one little letter for a person who’d already fled with their life and little else, or survived a concentration camp?

Despite everything he endured—the loss of liberty and profession and home, the murder of his brother—our Opa never lost his love for the storybook town of his childhood. In the German-language night school classes he taught after retiring from the New Jersey chicken farm, he would routinely pass around a picture book of Wertheim so that his students could admire the town’s history and charm.

It helped that Wertheim took steps in the mid-1970s to rebuild a relationship with its surviving former Jewish residents. A remarkable mayor named Karl-Josef Scheuermann made it his mission to locate them all over the world and extend a hand of friendship. Our Opa welcomed the contact and hosted the mayor when he came to the United States to visit.

In 1976, when the town commissioned a memorial plaque for the site where the synagogue once stood, our grandfather traveled to Wertheim for the dedication. As the oldest former resident in attendance—he was 86—he was invited to give some remarks. We have a copy of his words, and often wonder at their gentle, appeasing tone. “Forgiving and forgetting are often spoken of together,” he noted. “We can forgive, but we can never forget. A new and different Germany has arisen, a new generation has grown up.”

“How,” he asked rhetorically, “could we hold today’s Germany responsible?”

Our Opa was a kindly and gentle man by nature, but his magnanimity perplexes us a little. A mayor’s friendship and a town’s welcome seem a slender foundation for forgiveness of crimes so vast and, for our Opa, so personal. Would it have affected his judgment, we wonder, to know that the German government was then still riddled with former Nazi Party members? That most of those charged with Nazi crimes in the decades after the war had been acquitted by German courts? That a judge who denied his postwar restitution claim was a former Nazi? That even as he spoke, on a shelf a few blocks away, the swastika-emblazoned record of his birth still identified him as Felix Israel Müller?

We can’t say for sure whether this would have mattered to him, but it matters to us. Some German cities and towns did dig back into the Bürger-Bücher in the decade after the war to note the repeal of the Nazi renaming law. Such a notation appears, for example, on our grandmother’s birth record from the town of Donaueschingen even though she didn’t request it. The notation, dated Aug. 30, 1947, states that “the above note in the margin regarding the additional first name ‘Sara’ is canceled by operation of Order 10 950 of the Interior Ministry of Baden dated 10 June 1947.”

We can’t know how many towns’ birth records still stand uncorrected, like our Opa’s does. A web search turns up similar examples from the towns of Oberellenbach, Netra, and Hildesheim. There are surely others.

Would Wertheim entertain a specific request from us to correct our grandfather’s record today? Or would the town maintain that such a request woud have needed to come from him while he was still alive?

We don’t know, but the burden shouldn’t be on us. As it stands, the Nazis got the last word on our grandfather’s name and the names of untold numbers of others. It is time for all German cities and towns to take the initiative to check their birth records for these traces of Nazi law and correct those it finds. Yes, this will be an administrative burden. But if the government could devote the time to affix this stigma then, a new democratic Germany can take the time to remove it.

Eric Muller is a law professor and writer living in Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

David Muller is an investment professional living in Weston, Connecticut.