Objects of War

My grandfather fought the Nazis in WWII, and brought home war trophies, including a belt buckle and a helmet with swastikas on them. Now that I’ve inherited them, I wrestle with what to do with them.

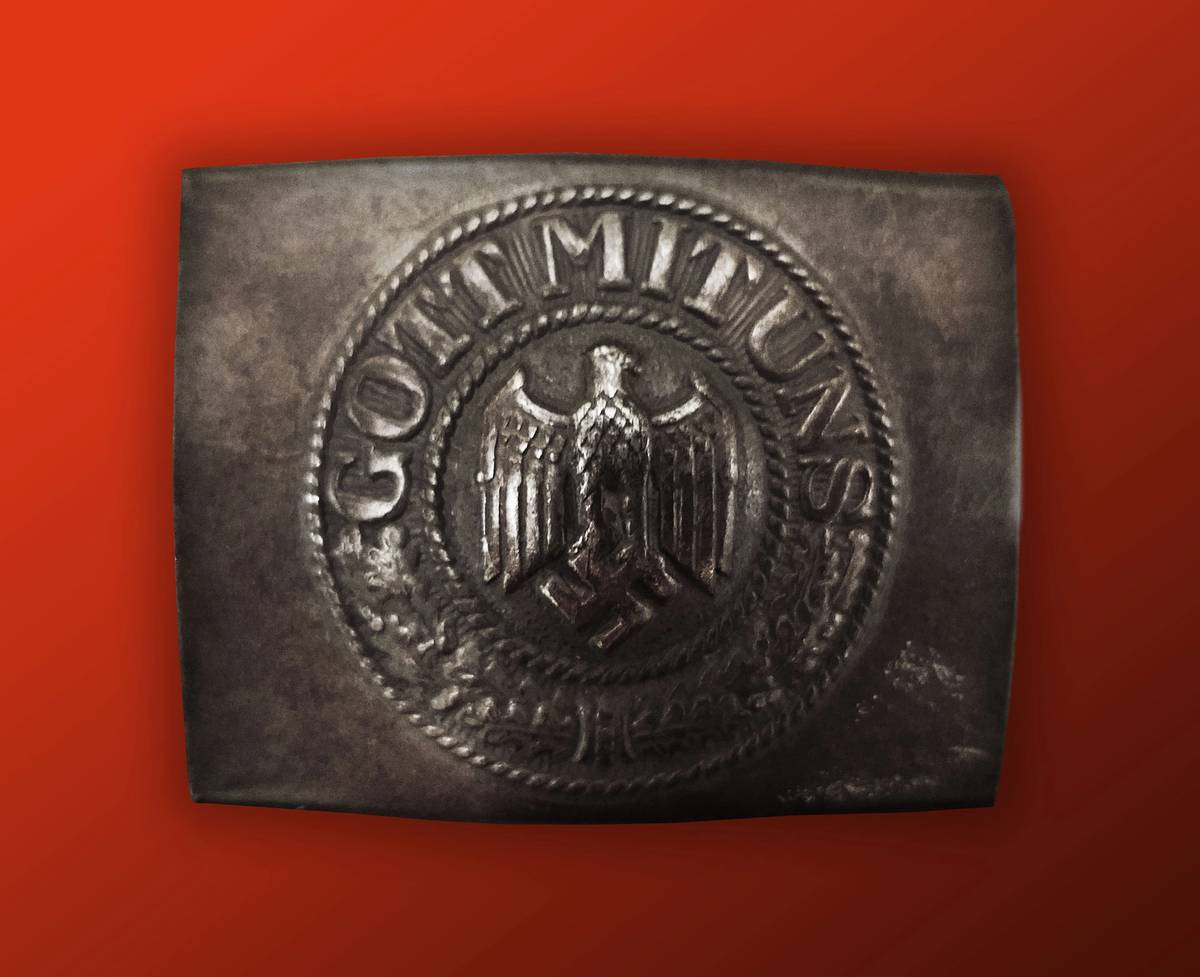

A few times a year when I was a child, my dad would take a belt buckle out from a bin he kept under his bed. The buckle is inscribed with the words “Gott mit Uns,” German for “God with Us,” an appeal to the God I worship as a Catholic, written in the language of my German ancestors. Under these words was a swastika. My father would place the belt buckle next to a helmet also inscribed with the same symbol. Surrounding the belt buckle and helmet were other items: my grandfather’s dog tags, his bombardier wings, a journal, and photographs.

Through these items, he would tell me and my brothers about his German Irish father, who rose from the poverty of the Great Depression to serve as a B-17 bombardier in WWII, who was shot down and captured by the Germans, who returned home and after the war served our community in north central Pennsylvania as the town’s dentist. He died before he had grandchildren, so it was up to my father to keep his story alive—with the aid of these items.

My grandfather never explained what he wanted to happen to his war trophies, how to preserve his legacy, or how to discuss the swastika with future generations. He was proud of his service, and grateful to play some hand in defeating the Nazis. But he was mortified by the destruction he brought Germany. He was half-German, and our hometown of Saint Marys, Pennsylvania, was founded by German Catholics in the 1840s as a means to escape religious persecution in the Old Country. In these items under my father’s bed, my family saw the heroism of a German Irish American who fought the evils of Nazism. He left a legacy to follow and conserve, but no instructions on how to do so.

I once thought my father never found the answer himself, and part of my inheritance has been to face this dilemma. The burden of these items is now my burden. The duty of keeping my grandfather’s legacy alive is my duty.

Growing up I had little exposure to Nazi memorabilia outside of my grandfather’s war trophies. The one exception was a flea market along a rural stretch of highway in Amish country that my friends and I frequented as teenagers. Vendors would sell other WWII items with the swastika: silverware, patches, uniforms. At this flea market, I learned the belt buckle and helmet had value beyond their attachment to my grandfather.

I was never taught to distrust or resent those who collected war memorabilia for personal reasons, including Nazi artifacts. The collectors I encountered were mostly odd but sincere. When I was a child, these items were my way to learn about my grandfather. As a teenager, I learned of their monetary and historic value to collectors. Since then, I’ve learned how others collect these same artifacts out of sympathy for the evil values they represent.

Many families of WWII veterans take a more casual approach to such memorabilia. They are trophies of war, nothing more. This works for most, yet it never seemed appropriate for my family or community. To this day, German American is the largest ethnic identity among white Americans, and over 40% of Saint Marys’ residents claim German roots. The town maintains its German American heritage in a variety of ways, including the town’s official flag. German was still widely spoken there when my grandfather was a child, and during his teenage years many community leaders embraced isolationism in response to the rising Nazi regime. As a result, our German ancestry and the town’s history call for a more careful attitude.

I was always proud of my grandfather’s military service. His sacrifices for my family and country compelled me to enlist in the Air Force after high school. And those war mementos, even the ones containing the ultimate symbol of hate, played some small role in my decision to follow his path into service. Those evenings at the kitchen table with my father and brothers, with the belt buckle, helmet, dog tags, bombardier wings, the journal, and photographs spread out before us had clearly influenced me. He served his country as a Boeing B-17 bombardier during a time of war. I served as a Boeing C-17 loadmaster in the conflicts that have defined my generation.

Just as his military service brought him to Germany decades before, my military service did the same. Whenever I passed through Germany on missions to Afghanistan, I reflected on my grandfather’s service, our German ancestry, and the swastika-emblazoned war trophies he brought home from that land.

My family never made much of our German ancestry. But the weight of history is inescapable. Almost 200 years ago, my ancestors fled Germany. A hundred years later, my grandfather returned to liberate it from itself, only to be shot down and captured. His heroic efforts contributed to Germany’s destruction. He returned home, consciously or not, bringing those Nazi symbols with him, to remind future generations of the war, the ruin, and the hand he played in freeing a people from themselves. In no small way, the people he liberated were our people, the towns and cities that lay in ruin were not so different from our German Catholic town, tucked away in the hills of Pennsylvania.

This family arc—from Germany, to Germany, from Germany, to Germany—was there as I walked the streets of Nuremberg. I would look up and try to imagine my grandfather, crammed in the nose of a warplane, on his way to bomb such beautiful city streets. I would imagine men marching in helmets, like the one my dad put on our kitchen table when discussing his father. I would envision men wearing belt buckles with “Gott mit Uns” etched on them.

These experiences caused me to rethink these objects. Buying or displaying items containing the swastika, including war memorabilia, is illegal in Germany in most circumstances. When I look at that helmet, I think of my grandfather with pride. I was taught to do so. However, to others, they feel shame—brought on by the thought of their ancestors’ conquering lands and slaughtering Jews.

Since returning home from Germany and separating from the service, I’ve continued in my grandfather’s footsteps. I completed my education and returned to our hometown to serve the community in local government and politics. Just as my grandfather passed these items on to his son, my father has now passed them on to me, and I’m left with the question, what is one to do with heirlooms that explain family history, but are symbols of hate to so many?

Living as an adult in my rural corner of Pennsylvania, I’ve seen others in rural Pennsylvania who gravitate toward Nazi memorabilia for unsettling reasons. By rural standards, a white supremacist compound sits not far from my home. For me, my grandfather’s war trophies have sentimental value; for collectors, they have monetary and historical value; for Germans, they are reminders of national guilt; but for these individuals, their value is in their power to express hate. It saddens me to think that some would revere the Nazi regime if they were to see the belt buckle and helmet, rather than my grandfather who fought to end their rule.

My relationship to these items has become more complicated and the questions about their future more worthy of consideration. The helmet and belt buckle could be donated to a museum, ensuring they are preserved in their proper context. However, in doing so, I would be giving up a piece of my grandfather and the items that aid in telling his story to future generations in our family. I have no desire to sell them or give them away, though they could be destroyed in order to keep them out of irresponsible hands. But wouldn’t that only affirm that the swastika truly has evil power and that the words “Gott mit Uns” are forever tainted?

Now that I’ve matured—and seen the swastika and war memorabilia in other contexts—I understand the approach taken by my father and my grandfather before him. These items were never paraded around our home lightly, they were not casually displayed, and I was taught to view them with respect. So it turns out I was left with instructions on how to preserve my family’s legacy after all.

For now, they sit, not in my grandfather’s closet, or under my father’s bed, but in my closet. And once more I will follow in my grandfather’s footsteps. They will only be brought out, along with the dog tags, the bombardier wings, the journal and photographs, to be placed on a table. And around that table the next generation will learn of their German Irish great-grandfather, who rose from poverty, served in war, and returned home to serve his German Catholic community. They will also learn these are symbols of hate, capable of causing immense shame or fear, and they are to be treated responsibly.

And if they point to the belt buckle with the swastika and ask, “What does ‘Gott mit Uns’ mean?” I will say it is German for “God with Us.” Indeed, God is with our family. He was with my German Irish grandfather in a warplane over Germany.

Seth Higgins was a spring 2021 Tablet Fellow who focuses on rural America.