The Outback’s Jewish Museum

Once it was a synagogue serving Jewish immigrants in a remote Australian mining town. Today, it’s a reminder of a history many have forgotten.

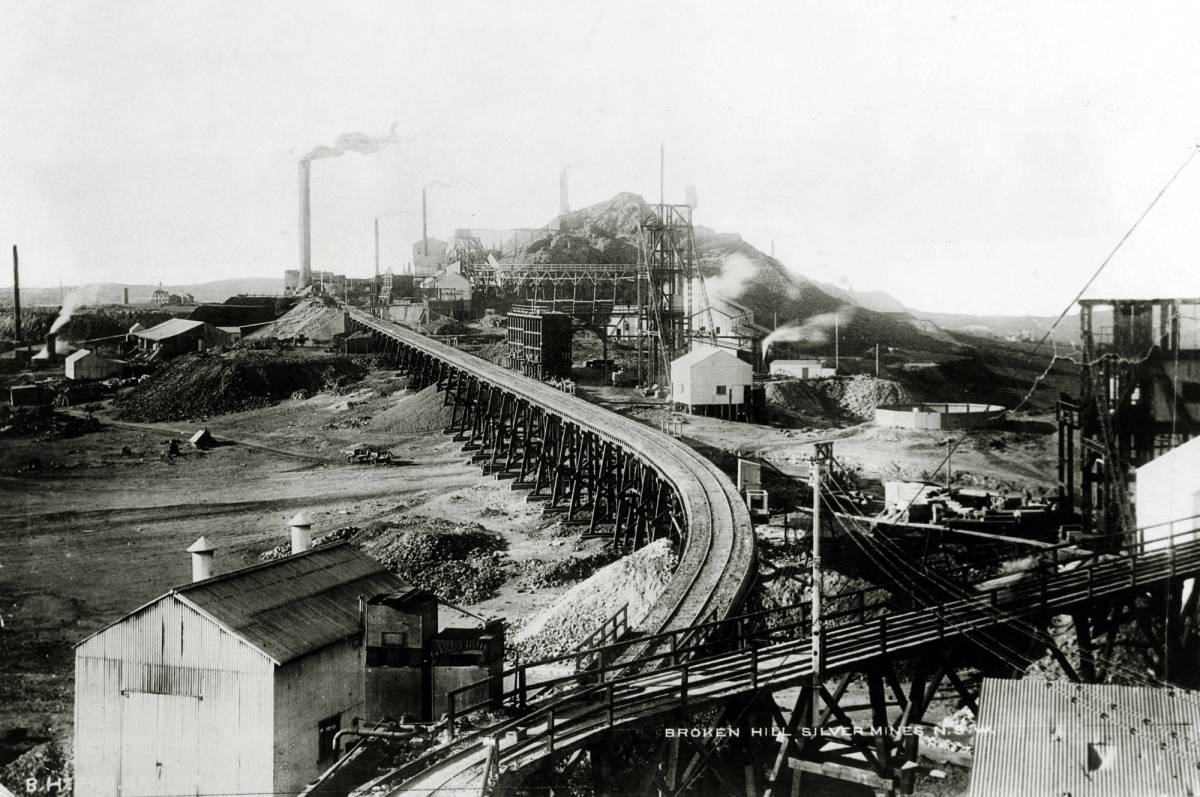

Broken Hill—an isolated town surrounded by desert and red earth in the middle of Australian outback, some 715 miles west of Sydney—was put on the map in the late 1800s as one of the country’s top mining towns. Huge deposits of iron ore, silver, and zinc were discovered there at the end of the 19th century, leading to a flurry of migration. The town is the ancestral home of the Broken Hill Proprietary Company, which today is still one of the world’s largest mining companies.

Among the mining frenzy that began in the late 1800s, a small group of Jewish settlers, mainly from Europe and Russia, began to make their way to the town. A Jewish cemetery was consecrated in 1891 and a foundation stone for the Broken Hill Synagogue was placed at 165 Wolfram St. on Nov. 30, 1910. In its heyday from the 1910s to the 1960s, the synagogue served the approximately 200 members of the Jewish community.

Today, Broken Hill remains isolated: This town of 17,000 is a three-hour drive from the next town of more than 1,000 people. These days, there is no active Jewish community. The synagogue still stands, but in 1991 it was converted to the Synagogue of the Outback Museum, which is owned and maintained by the Broken Hill Historical Society. Behind a stone façade, the building comprises the former rabbi’s residence and the synagogue, which includes the original pews, lectern, and ark, as well as a replica Torah on display. The museum is open three days a week; approximately 40 people visit each week, including the occasional school or Jewish group. And this April, the museum will hold a special Shabbat service—only the second such service at this location since the 1960s.

“Broken Hill was known around the world as a place where there was opportunity and wealth to be earned from the rich ore deposits discovered in the 1880s,” said Leon Mann, a professor of psychology who was born in Broken Hill in 1937 and co-authored Jews of the Outback, a history of the Broken Hill community. Mann’s parents, like many in the community, migrated to Australia from Eastern Europe and British Mandate Palestine. “My parents arrived in Broken Hill In 1929 during the Great Depression,” he said. “There was still work in Broken Hill from silver, lead, and zinc mining. The entrepreneurial Jewish community who supplied and provisioned the miners fared quite well.”

Armed with the knowledge that Broken Hill was prospering, Jewish immigrants, who were often fleeing pogroms and antisemitism in their home countries, decided to settle in the remote outback of Australia. Among the Ukrainian Jewish immigrants, many already possessed knowledge and experience in mining, as they came from the Donetsk region, which had similar industries. Many of the immigrants set up businesses to serve the booming mining industry and Broken Hill Jews became involved in politics and the union movement.

Mann became fascinated with this remote Jewish community and has returned three times since his family left for Melbourne in 1942 when he was 4. “Broken Hill is an iconic outback town in regional Australia,” he said. “There are a number of exotic places in Australia, but Broken Hill on the edge of the desert and miles from anywhere is special.”

Aside from his personal connection to Broken Hill, Mann finds it remarkable that the synagogue built in 1910 still stands: “Broken Hill, with a [total] population under 20,000, has a synagogue which has become a Jewish museum. Is it believable? Imagine a Jewish museum in the Klondike, which had a gold rush in the 1890s!”

“There [have] always been Jews in Australia—since the first transport of convicts in January 1788, which included about a dozen Jews—and there have always been Jews and their families in outback towns usually running small businesses or hotels,” said Walt Secord, a member of the New South Wales state parliament who has visited the Broken Hill Synagogue Museum twice and takes an active interest in its well-being. “I have always been fascinated by Jews in the Australian outback and I was intrigued that a thriving Jewish community existed more than 700 miles west of Sydney in the middle of the Australian desert.”

The success of the Jewish community in Broken Hill, despite the hardships, continues to inspire him.

“When Jews started to arrive in Broken Hill in the 1880s, there was no natural water there and the region was served by Indian and Afghan camel drivers. All supplies including drinking water had to be carried to Broken Hill. But within years, Broken Hill had become the third-largest provider of silver in the world,” Secord said. “Living conditions were harsh and Broken Hill has always been gripped by drought. It did not have a stable water supply until recently—that is, more than 130 years later.”

While there are no known Jewish descendants left in Broken Hill in 2023, Secord knows that the synagogue tells the long-forgotten story of Jews in rural, regional, and remote Australia. “The synagogue is more than 110 years old. The community was so vibrant and active that it raised money for the Jewish National Fund. A certificate hangs on the wall in the shul. Jews remained in Broken Hill until the 1960s. Today, their descendants are scattered all across Australia.”

When the Jewish community in Broken Hill declined, the synagogue closed in 1962, and the remaining Jewish men in Broken Hill rented the residence adjoining the building to try and keep it up, before the synagogue was sold and purchased in 1990 by the Broken Hill Historical Society. Today the museum coordinator is a volunteer named Margaret Price, an 82-year-old Australian woman who is part of Broken Hill’s Historical Society. For the past 16 years, she has curated exhibitions on everything from the immigrants who made up the Broken Hill community to traditional Jewish clothing owned by previous members of the community. In addition, she shepherds through the visitors who come to tour the museum.

“When I started here, there was a table, an 18-inch word processor, and two filing cabinets and a cupboard in the office,” she said. “Now the room is so full of folders, filing cabinets, shelving, cupboards, and I’m still discovering new things about the Broken Hill Jewish community.”

While Price was born and bred in Broken Hill, which today has no active Jewish community, she has always known Jewish people and went to school with a Jewish girl. “Our life [in Broken Hill] had Jewish people in it,” she said. “There was a Jewish doctor in Broken Hill. He delivered three of my children and my baby sister. I left school and worked for a Jewish man. I shopped in Jewish shops.”

Price does not consider herself Jewish, but she believes that her ancestry holds some Jewish lineage. “I’ve always been fascinated by Judaism,” she said. “Even as a kid. Both of my grandparents on my dad’s side had Jewish ancestry. But everyone changed their names getting on and off the ships. We can’t [formally find a] link.”

The synagogue has been operating as a museum now for many decades. Price fondly remembers back to 2018 when the first group of Jewish visitors came to hold Broken Hill’s first Shabbat services in years. The mission was led by Rabbi Shneur Reti-Waks, a congregational rabbi from Melbourne, who brought a group of 60 Jews from across Australia, many of whom had personal connections to the Broken Hill Jewish community. The group visit made the front page of the Broken Hill newspaper.

“The shul closed in the 1960s for regular services and our group was the first time services had been held there since,” said Reti-Waks. “It was one of the most emotional things I’ve been part of. You felt the presence of everyone there. The incredible story, the idea that you had this vibrant close-knit Jewish community that used to live in Broken Hill.”

The group also trekked to the Broken Hill cemetery, where they saw many of the Jewish gravestones and recited Kaddish. “It had such an intensity. Not so much from sadness and grief, but from a feeling of presence and all those that were,” said Reti-Waks.

After an extended hiatus in showing visitors through the museum due to the pandemic, Price and Mann have upcoming plans to host another Shabbat service at the Broken Hill Synagogue in April 2023, only the second formal service since the 1960s.

In addition to the Shabbat service, the two have plans to hold a naming ceremony for two benches that will be placed outside that will honor important former members of the Broken Hill Synagogue. One bench will honor Reverend Abraham Berman (a title used by many Orthodox rabbis in early Australian communities) and his wife, Franziska Berman, the synagogue’s last full-time rabbi and rebbetzin, who left Broken Hill in 1944; the second bench will honor Alwyn Edelman and Harold Griff, a former trustee of the synagogue and former Broken Hill Historical Society president who undertook the agreement to transfer the old synagogue to be identified and maintained as a Jewish building in perpetuity.

It’s an energizing event for Broken Hill that will surely attract a crowd.

Nomi Kaltmann is Tablet magazine’s Australian correspondent. Follow her on Twitter @NomiKal.