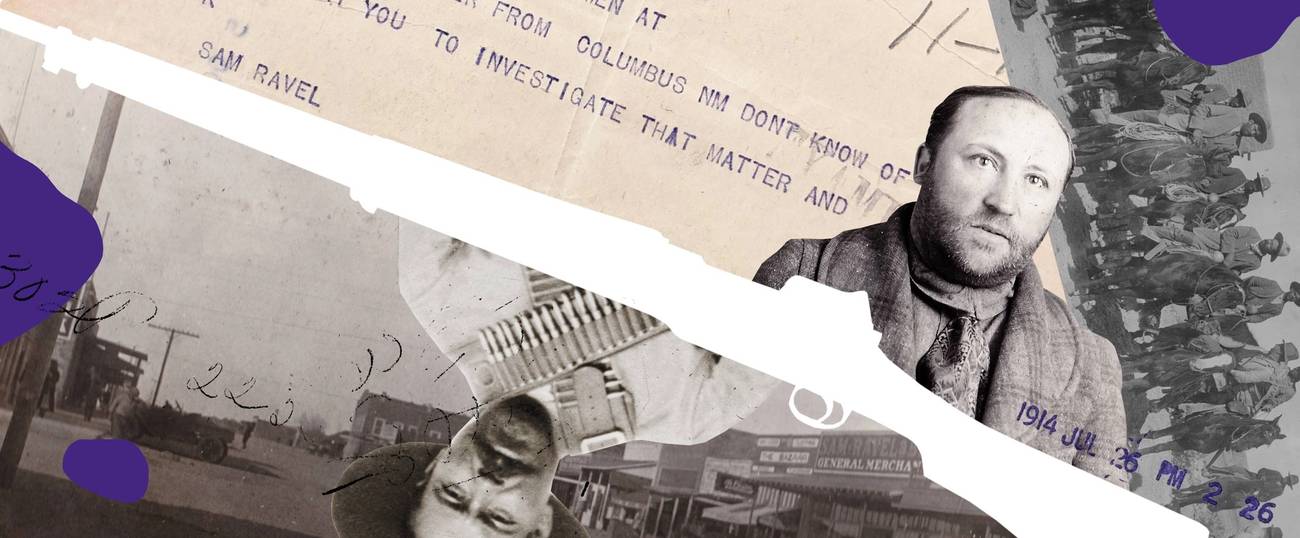

Pancho Villa and My Grandfather

Why did the Mexican revolutionary invade the U.S. in 1916? To find a Jewish merchant.

Scholars have debated for a century why Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa attacked the frontier town of Columbus, New Mexico, on March 9, 1916—a deadly incursion and infamously the only time in the 20th century that a major foreign army invaded the continental United States. According to my family’s most spectacular story, recounted at reunions with a quizzical smile, he was looking to kill my grandfather.

Villa was likely motivated by a constellation of reasons, but most accounts note a grievance with a prominent merchant named Sam Ravel, whom the Villistas desperately sought on that murderous March night. They did not find him; Ravel—my grandfather—was in El Paso for a medical appointment.

The story has long intrigued me, even as I wondered if it was true. How did a Jewish immigrant from Lithuania land in a dusty border town and get tangled up with one of Mexico’s most notorious figures?

*

To learn more, in March 2016 I joined family members on a pilgrimage to New Mexico to attend the annual Columbus Memorial Day service, which that year marked the centennial of the raid. As we drove west on Highway 9 from El Paso, peering to our left for a glimpse of the border, my cellphone service vacillated between AT&T and Mexico’s Movistar provider.

A military affair, the program began with a border patrol color guard and ended with taps. We listened to speakers, took a walking tour of the town, and then headed across the border for lunch in Palomas, Mexico.

The next day I flew home to California with more questions than answers. A few years of intermittent research—including my discovery of oral histories and archival documents—have helped me fill in some, but certainly not all, of the blanks in this chapter of my grandfather’s life.

Sam Ravel was born in the shtetl Shaki (Sakiai), Lithuania, in 1885, the eldest of six children, during a period of Russian rule. Anti-Jewish pogroms were persistent and pernicious, and his future held induction into the czar’s army. To escape that fate, Sam immigrated to the United States, where other relatives had settled.

He arrived in Galveston, Texas, on Sept. 11, 1905 (59 years to the day before I was born), and headed to El Paso, where his uncles Erman, Joseph, and Max Ravel had already settled. Later he arranged for two younger brothers, Louis and then Arthur, and finally sister Dora, to join him in America.

He was, by family accounts jocular, short, and fat, a physical description affirmed by his 1920 U.S. Citizens’ Identity Card for Use on the Mexican Border, which lists his measurements: 5-foot-2, 180 pounds. In a 1968 oral history for the University of Texas at El Paso, his cousin Vincent characterizes Sam as a religious man who “never missed a Friday night in synagogue.”

Soon after Sam arrived, he and his uncle Joe opened the City Loan & Jewelry, a pawn shop on South El Paso Street. El Paso was a rough town; shootings and robberies were not uncommon and prostitution and gambling flourished. It must have been a culture shock for a Yiddish-speaking 20-year-old, but it was a good place to learn English and Spanish—and get to work.

According to the oral history interview with Vincent, one day a Mexican man walked into the shop to purchase guns and ammunition. A small crowd formed outside, peering into the store windows. The Mexican paid in cash and departed.

Later that afternoon the authorities showed up at City Loan & Jewelry. “Do you know who that was?” they asked. “That was Pancho Villa.” It was likely the first of many times that Sam’s and Pancho’s paths would cross.

*

The town of Columbus, about 70 miles west of El Paso, was established in 1891. Early boosters organized excursions for prospective real estate buyers from El Paso, treating them to barbecue and music and crowing that with New Mexican statehood on the horizon, Columbus was filled with opportunity—especially for cross-border trade. Indeed, by 1902 the U.S. government established a customs house and crossing connecting the village to Palomas.

Ready to strike out on his own and eager to make enough money to send for his siblings, Sam moved in November 1910 to Columbus. It was a small town with few offerings, so he filled niches.

Q: Who discovered America?

A: Columbus discovered America

Q: Who discovered Columbus?

A: Sam Ravel

—Attributed to William McGaw, historian, founder, and publisher of the El Paso Journal

Travelers needed places to stay, so Sam bought the Commercial Hotel, which was lease-operated by William T. Ritchie. Inside of it, Sam opened the town’s first movie theater. He also established a dry goods store, the Columbus Mercantile Company, renaming it Sam Ravel & Brothers once Louis and Arthur joined him.

It was a typical “Jew store,” as these ubiquitous small-town establishments run by Jewish immigrants were known. They sold food, clothing, hides, shoes, hats, appliances, fuel, cleaning supplies, guns, ammunition—you name it.

Their customers were as diverse as the merchandise: Americans, including families of the 13th Cavalry Regiment stationed at Camp Furlong, and Mexicans, some representing revolutionary armies that were jockeying for power. It seems likely that Villa was a customer and, if family lore is true, a once-in-a-while player in the poker games held at night in the back of the store.

Was Villa a noble hero, savior to the downtrodden of Mexico? A murderous bandit? A trusted American ally? It depends on when and whom you asked. The Ravel brothers didn’t agonize over their customers’ activities. As Arthur said in an 1960 interview with McGaw, also for the UTEP Institute of Oral History, “when you come into our store and you buy a box of ammunition or you buy a rifle, it’s none of my business to ask you where you’re from or where you’re going.”

*

Palomas in the state of Chihuahua is a small town of fewer than 5,000 people, just minutes south of Columbus. Today, Americans venture over for low-cost prescription drugs, cheap dental work, or eye examinations with same-day eyeglass service.

After the raid commemoration, we walked across for lunch at the popular Pink Store, where a Villa impersonator jauntily prances on the dance floor and poses for pictures.

For Sam, the Mexicans in Palomas—including the revolutionary factions that came through—were important customers. So on July 22, 1914, when he received a letter from Captain Azcarate requesting he come to Palomas for a big order, he happily obliged.

On July 23, 1914, Sam crossed the border to deliver Azcarate’s order. The two men kibitzed for an hour or so, and according to Sam’s own written account that he sent to the attorney general of the state of New Mexico, Azcarate introduced Sam to a Captain Arroyo as “an old friend who could get him anything he needed.”

Indeed, the Mexicans ordered more goods and Sam returned the following day to deliver them. But when he began to head back to Columbus, Azcarate beckoned him to his office.

“He showed me a letter from Mr. (Leoncio) Figueroa,” said Sam. It was an arrest order. “Azcarate then told me that the letter didn’t amount to nothing because he knew me well,” explained Sam, but then he showed Sam a telegram from Juarez headquarters that insisted orders be followed.

Though the charges were unclear, Sam was arrested on the spot and taken to a guardhouse. He was held there for two days. On Sunday, Sam asked Arroyo if he could at least sleep in town, and Arroyo consented, as long as a guard came along.

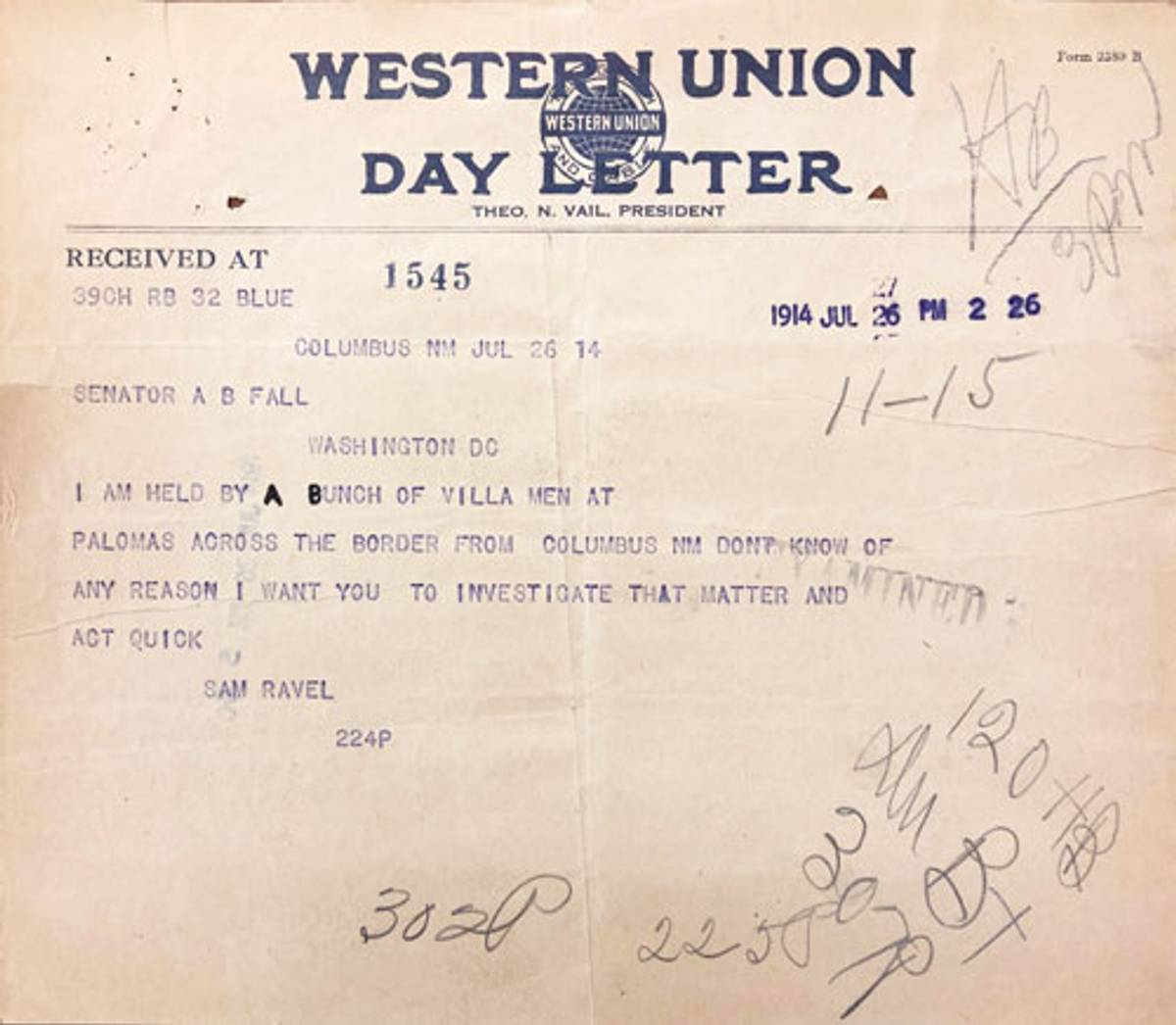

Presumably during this time in town, Sam sent a telegram to his senator, Albert B. Falls, explaining he was held by “a bunch of Villa men” and asking for help. The next day he was released.

The Deming Highlight of New Mexico headline read “Sam Ravel in Trouble” and reported that he was arrested in Palomas by Constitutionalists—another revolutionary faction—for supplying the Roque Gomez gang with arms and ammunition.

*

An octagonal Seth Thomas clock from the Columbus railroad depot now hangs in the New Mexico History Museum in Santa Fe. It’s a standard timepiece from the early 1900s, with one exception: A bullet hole above the VI, which disabled the pendulum at 4:12 a.m. The depot withstood copious crossfire in the early hours of March 9, 1916, including a hit to this clock, now forever stalled to remind us when the raid occurred.

The War Department estimated that 500 to 1,000 of Villa’s men on horseback galloped into town, guns blasting and shouting “¡Viva Villa!” While it is generally thought that Villa himself led the troops, no eyewitness could positively confirm his presence.

Sam was nowhere to be found, having left for El Paso the day before. But brothers Arthur and Louis were present.

Sixteen-year-old Arthur, asleep in the family house a block from the store, was awakened by a commotion—shooting and shouts of “¡Viva Mexico, mata los gringos!” Armed bandits burst through the front door looking for Sam. They grabbed Arthur by the arms and forced him to the store, where they tried to coerce him to open the safe. Whether as a ruse or in sheer terror, Arthur couldn’t remember the combination. The men shot at the safe door, but to no avail.

Louis was asleep on a cot in the store. Hearing the ruckus, he scrambled to the back and hid beneath a large pile of cowhides from whence he heard shots fired, windows and display cases shattered, and all manner of chaos. “The hides,” he said to McGaw during the 1960 UTEP interview, “saved my hide.”

Continuing their hunt for Sam, the Villistas marched Arthur to the Commercial Hotel. The town, recalled Arthur, was ablaze, “a regular inferno, just hell.” Room by room they searched for Sam.

Villistas had overtaken the hotel, ransacking as they had all over town. An officer commanded them to spare the women and children, but to kill all American men. They ordered the men downstairs, and hustled Arthur along with them.

At the foot of the stairs the Americans were abruptly told to leave. But as they started to run, they were shot. In this manner, Arthur witnessed the killing of hotelier Ritchie, veterinarian Harry Hart, and John Walker, in town for a Sunday school convention. The Villistas set fire to the Commercial Hotel, which burned to the ground.

Arthur thought he was a goner, too. But the Mexicans had other ideas, dragging him through town as they continued their frantic search for Sam. By then the American soldiers advanced, a gunfight ensued, and Arthur’s captors were picked off, one by the drugstore and the other at the city water tank. Arthur escaped unharmed, save a notch where a bullet grazed his left ear.

By daybreak the Villistas retreated. But the body count was grim: Nine local military officers, 10 civilians, and approximately 78 members of Villa’s army were killed.

*

Theories abound as to why Villa raided Columbus. Some say that his supplies were dwindling, so he intended to raid the town and an adjacent military garrison to restock. Others assert that Villa sought revenge against the United States because President Wilson had recognized the government of Villa’s sometimes collaborator/sometimes rival, Venustiano Carranza, who was president in the waning years of the Mexican Revolution.

Numerous accounts repeat a rumor that Villa had paid for, but never received, weapons from Sam. Others contend that Sam sold faulty weapons to Villa, or that Sam had ceased selling goods to Villa because the revolutionary leader’s fluctuating currency was valueless.

Author Eileen Welsome, in her book The General and the Jaguar, quotes Villista Juan Muñoz as follows: “We went to Columbus to take Sam Ravel and burn his properties for the robbery and treason which he committed. Èsa es la verdad.” (“That is the truth.”)

But is it?

Arthur repeatedly repudiated charges that Sam had anything to do with Villa. In 1960 he said to McGaw in the oral history interview “My brother, who was the head of the firm at that time, he did business with every revolutionary concern, bandit, or general—whatever you want to call them—that came to Columbus. With the exception of Pancho Villa. He never did any business with Pancho Villa. Never.”

McGaw, who conducted extensive interviews with residents who endured the raid concurred, saying, “No one that I’ve talked to in Columbus believes such a thing.”

Friedrich Katz, the foremost 20th-century scholar of Mexican history, wrote in a letter that “although a number of oral sources state that Villa went to Columbus to find and punish Ravel for having defrauded him of ammunitions and other goods that he had ordered, I found no corroboration of any of this in any written source about the raid.”

Yet my uncle Arthur’s assertions that Sam never had dealings with Villa seems preposterous. Sam’s own account of his capture in Palomas confirms he conducted business with people he perceived were Villa’s agents.

Was Sam targeted as the town’s most prominent merchant? Did anti-Semitism factor into whisperings that the business dealings at the “Jew store” were underhanded? These and many other questions remain unanswered.

During his interviews in 1960 with Louis and Arthur, McGaw summed it up best. “To find the true facts of something that happened only 45 years ago is so difficult,” he mused to Arthur, “that you wonder how in the world they ever got any correct history about the Revolutionary War or something that was one hundred or so years ago!”

*

It’s generally agreed that one of the most important outcomes of the raid is the Punitive Expedition that followed—an attempt to capture Villa led by Gen. John J. Pershing. Pershing went on to command American forces on the Western Front during WWI, and the difficulty of the terrain and mission in Mexico are credited with expertly training the U.S. soldiers who later fought in Europe.

With 10,000-12,000 troops headed to Mexico, a large support depot was needed, so the army established a supply base at Camp Furlong. Thus, by late 1916, Columbus was indeed booming, though not in a way that early boosters could have anticipated. Including camp personnel, the city had the largest population of any in the state of New Mexico.

Villa evaded Pershing’s army as they chased him through northern Mexico. After 11 months, the Americans returned home empty-handed.

Political turmoil continued in Mexico, and in 1920 Carranza was assassinated. Adolfo de la Huerta became the provisional Mexican president. To help stabilize the nation, he negotiated with Villa for his withdrawal from the battlefield. Villa agreed and “retired” in 1920. But he had made many enemies, and was gunned down in his car three years later on July 20, 1923, when he left his hacienda to visit a nearby town.

The Ravel brothers refused to file for bankruptcy after the raid, rebuilt their store in Columbus, and played a significant role in the town’s recovery. In 1917, Sam married New Yorker Anna Blumberg and brought her to Columbus. They had three sons: Herbert (1918–98), William (1921–81), and my father, Alvin (1928–95). The brothers continued operating their Columbus store until 1934. Sam and his family eventually returned to El Paso and he died there in 1937.

In death as in life, Villa’s legacy is ambiguous. “Pancho Villa’s” is the moniker of numerous American restaurants, and a park in Columbus is called Pancho Villa State Park, a name that rankles some old-timers. (It’s hard to imagine New Yorkers frolicking in an Osama bin Laden Park, but it’s a reasonable comparison.)

Today, an overarching sense of camaraderie between most Columbus residents and their Mexican neighbors pervades the region, in large part due to this shared history. Nothing better represents this aura of bonhomie than the Cabalgata Binacional Villista.

Each year for the past 20 years, a cadre of Mexicans on horseback commemorates the raid by embarking on the 200-mile, nine-day ride to Columbus following Villa’s route. Local municipalities along the way welcome the riders with food, music, and places to sleep.

In a show of friendship, American riders meet the Mexicans at the Columbus Land Port of Entry. Federal, state, and local authorities issue permits, provide traffic control, and otherwise graciously negotiate the bureaucracy so the horses and riders can cross.

Together a binational cavalry rides into Columbus. The event culminates in a fiesta for all on the town plaza. Viva Villa, indeed.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Stacey Ravel Abarbanel writes about art and culture and is a consultant for museums and other cultural organizations.