A Jew on Death Row

The tragic case of Pesach Rubenstein, sentenced to die in 1876 after a sensational murder trial

The reality is that prejudice is endemic and antisemitism will never entirely vanish. There has always been an ebb and flow to hating Jews—and at the moment that wave is cresting. Amplified by ugly outbursts on social media and nutty, albeit dangerous, right-wing conspiracy theories, Jews in the United States, Canada, and elsewhere yet again have been targets of random attacks of vandalism, harassment, and violence.

As bad as the situation is at the present, however, it was worse more than a century ago when discrimination was legal and Jews were not always accorded equal treatment of the law.

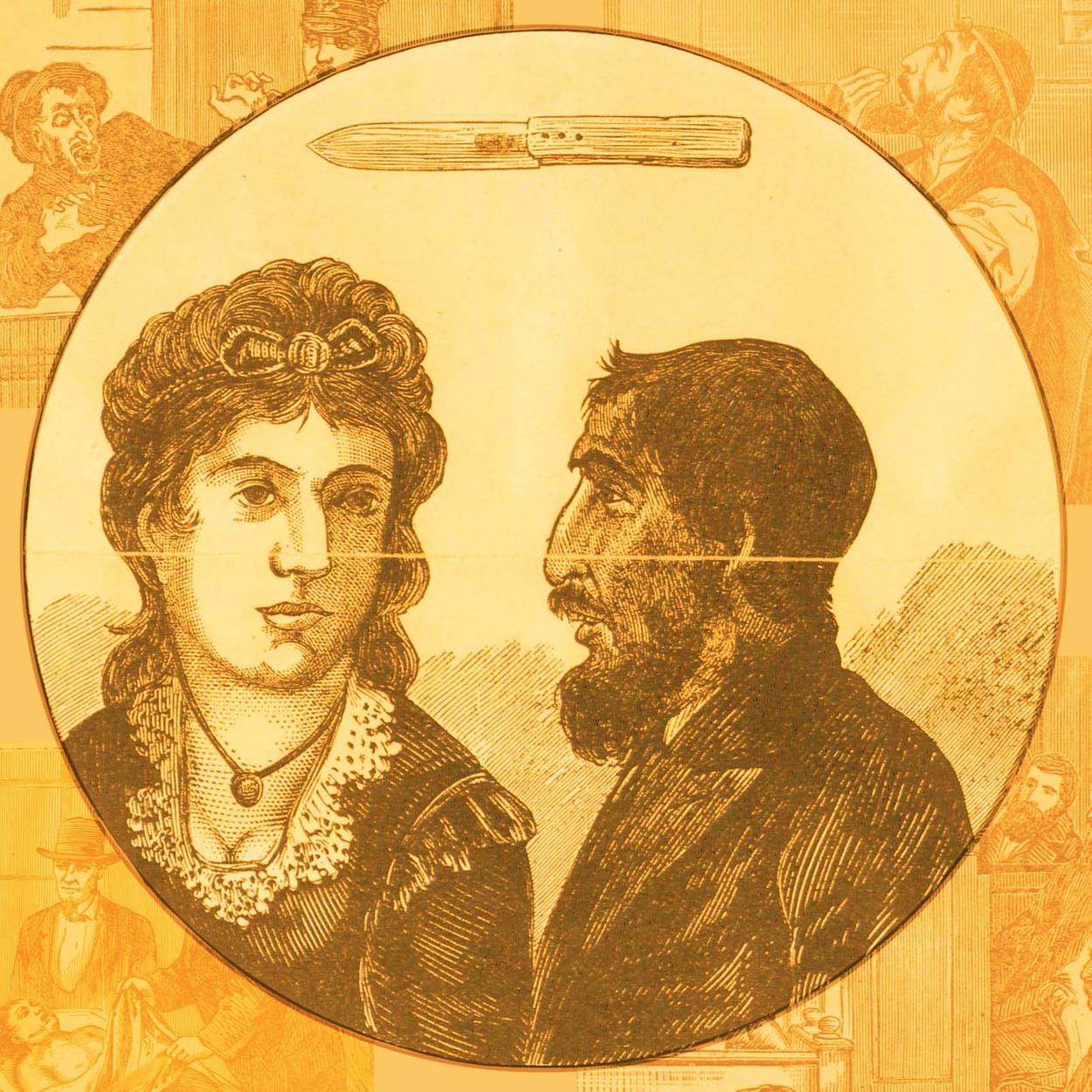

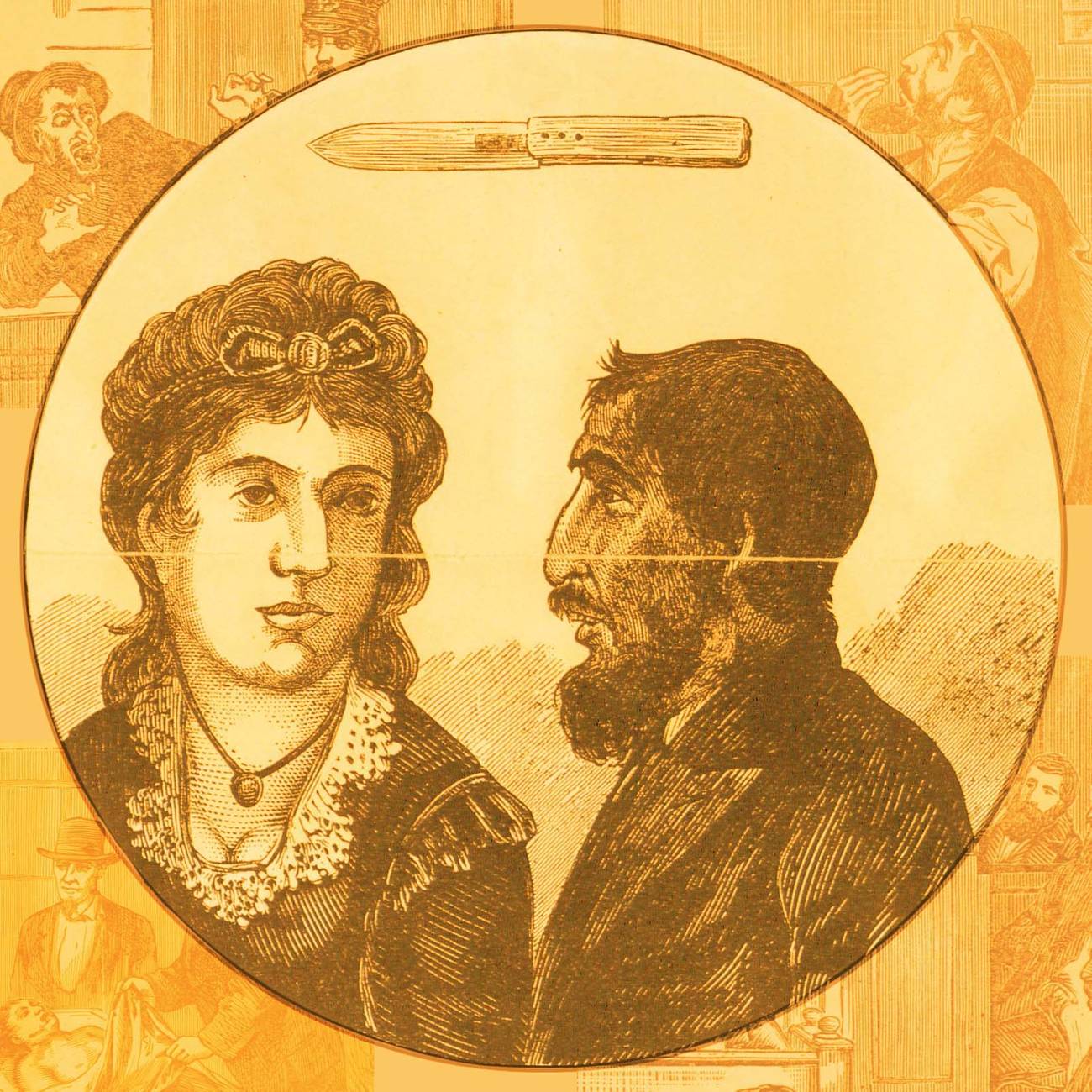

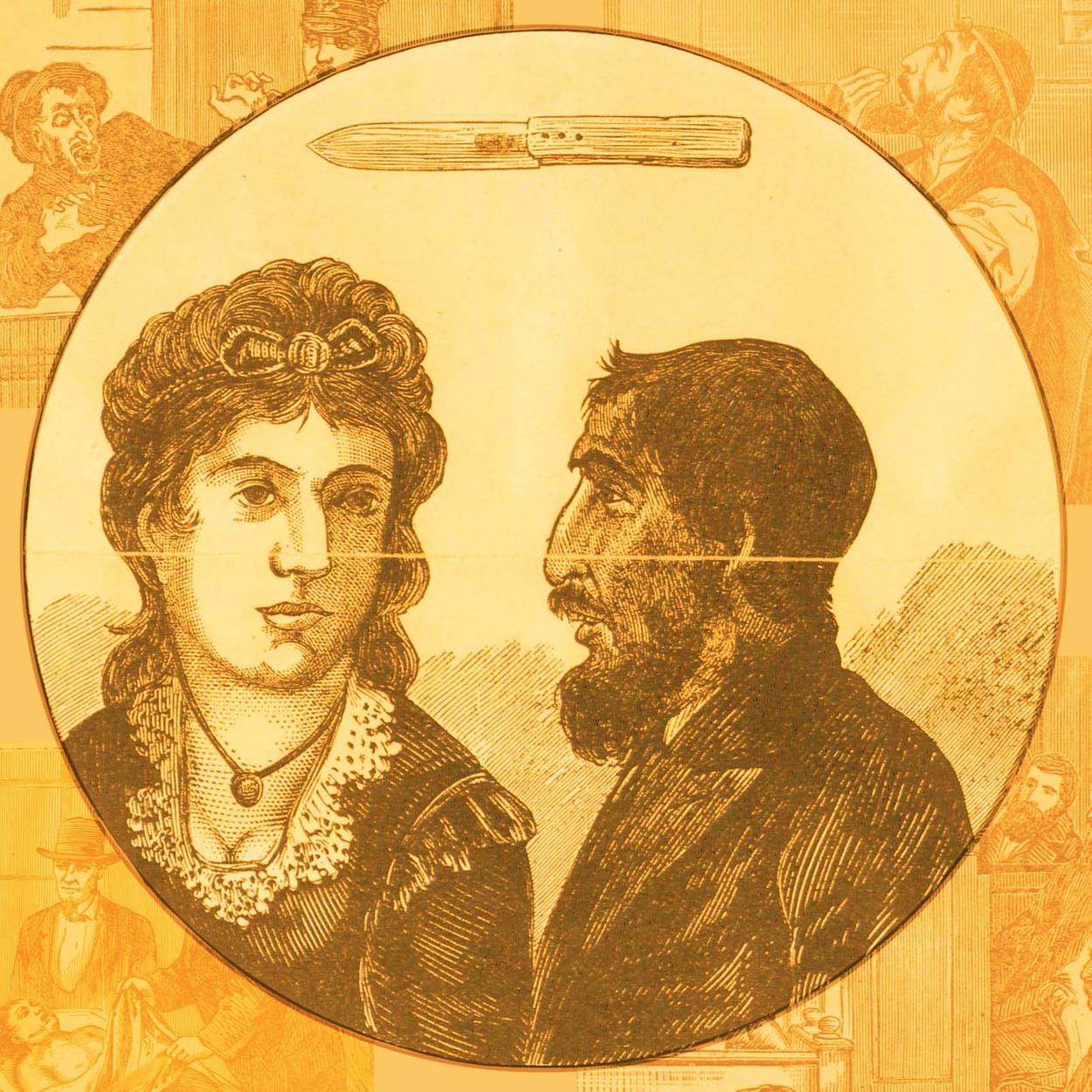

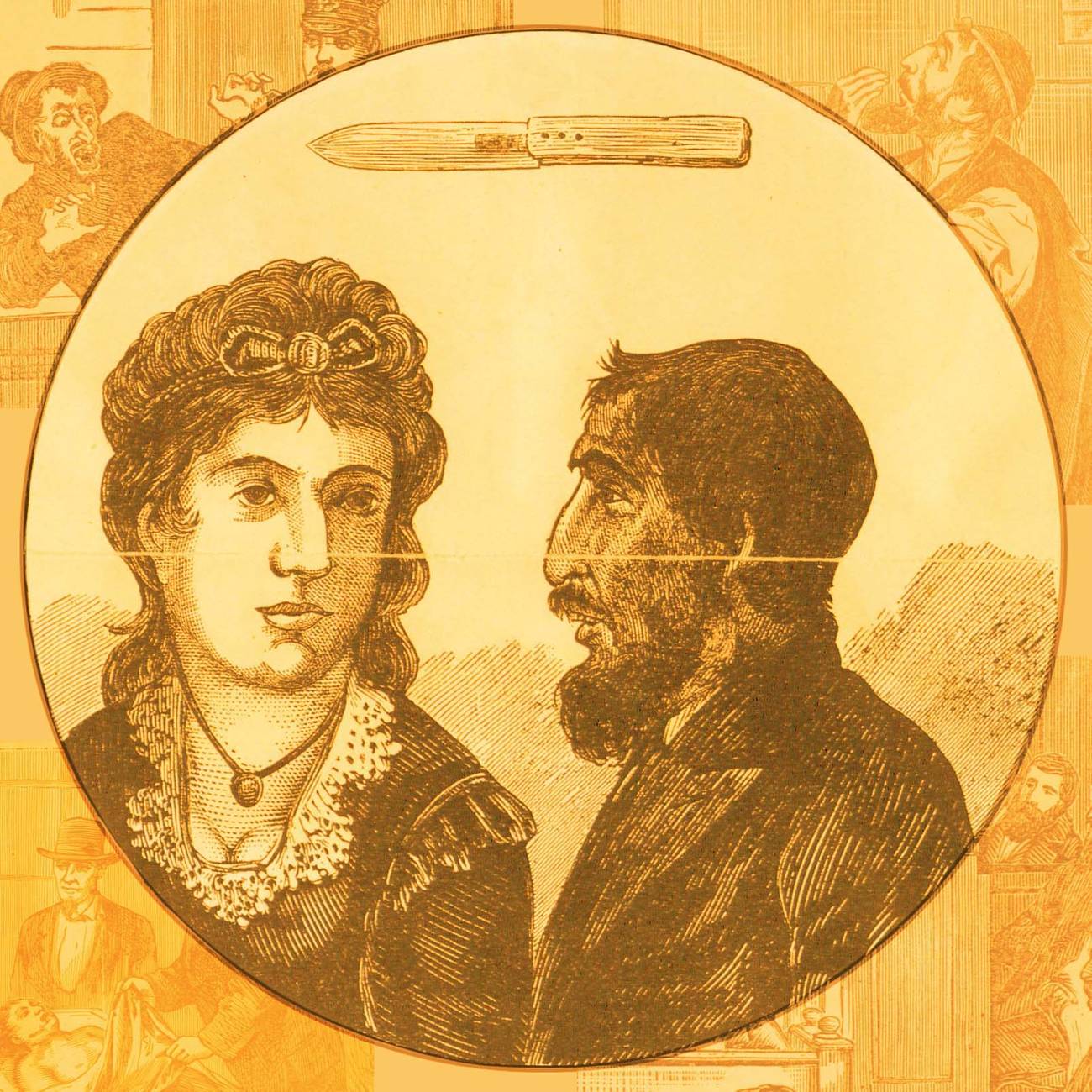

An early victim of antisemitism was a 30-year-old Orthodox Polish-Jewish immigrant who resided in New York City, close to where the Lower East Side and Chinatown intersect. His name was Pesach Rubenstein (called Pasach N. Rubenstein in the official trial transcript). His unfortunate claim to fame was being one of the first Jews (possibly the very first) in post-American Revolutionary New York and the United States sentenced to death, in an 1876 criminal trial that was tainted with antisemitism and sensationalism in the press. (By most accounts, the first Jew in North America sentenced to death was Moses Susman, who did not speak English and who was hanged long before the Revolution, in July 1727 in Westchester County, New York, after he was convicted of stealing gold, silver money, and jewelry from Moses Levy, a prominent Jewish merchant.) If not an outright miscarriage of justice, Rubenstein’s conviction for allegedly murdering his 19-year-old cousin Sarah (or Sara) Alexander—depicted as “The Murdered Jewess” in a widely distributed illustrated booklet—was based on circumstantial evidence, witness statements open to question, a prejudiced, if not blatantly antisemitic, district attorney, Winchester Britton, and an all-white male Christian jury who perceived the Yiddish-speaking Rubenstein (though he did know some English phrases) with his beard, peyot (sidelocks), and strange behavior as a suspicious alien to be feared.

In 1875, New York City’s Jewish population was approximately 75,000, which represented about a third of all Jews then living in the U.S. That number would dramatically increase following a huge wave of immigration in the post-1880 period such that by 1910, there were about a million Jews in New York, which accounted for approximately 25% of the city’s total population. While there were Jewish criminals, gangsters, and prostitutes in the world of the Lower East Side, most Jewish immigrants tended to stay out of trouble with the law; bad memories of interactions with police and justice officials in Russia and Eastern Europe no doubt reinforced such behavior. These newcomers may have been poor, but as Moses Rischin notes in The Promised City, his classic 1962 book on New York’s Jews in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Jews organized their own charities and mutual aid societies to take care of each other. Rischin adds that “prior to the 1880s only the Rubinstein [sic] murder case spotted the record of New York’s Jews.”

(He was mistaken. In August 1871, five years before Rubenstein’s trial—as historian Mia Brett, who has extensively researched the Rubenstein case points out—a Jewish abortionist in New York, Jacob Rosenzweig, was convicted of manslaughter after the body of a young woman, Alice Bowlsby, was found naked in a trunk at the Hudson rail depot. It was later determined that she had died from a botched abortion that Rosenzweig had performed.)

The pre-1880 Jewish immigrants often existed within a hostile environment (as did those in later years). American Jews were not denied citizenship and Jewish males had voting rights, yet as University of Pennsylvania historian Beth Wenger has argued, antisemitism was part of daily life. “From portrayals of Jews as weak, deficient, and deviant to depictions of them as shrewd, cunning, and determined to undermine and ultimately control all aspects of American life,” she has stated, “anti-Semitism fed into the very streams of American thought that determined who was and who was not legitimately an American. Indeed, these anxieties shaped both legal and social policy, strengthening campaigns for anti-immigration legislation and cultivating fears about ‘outsiders’ who allegedly threatened to invade and overtake the young American nation.”

A typical assessment of the era was offered by Matthew Hale Smith, an army chaplain and writer. In his 1869 book Sunshine and Shadow in New York, he voiced his concerns about New York already being overwhelmed with Jews. Some of them, he conceded, were respectable, but the majority were not. “Jews of the lower class are disagreeable, and their presence a nuisance to any Christian neighborhood,” he wrote. “If they get into a block, they infest it like the plague. Persons in search of a house invariably ask, ‘Are there any Jews in the block?’” Such were the negative attitudes that influenced the police investigation of Sarah Alexander’s murder, the quick decision to charge Rubenstein with the crime, and the trial proceedings that followed and sealed his fate.

On Tuesday, Dec. 14, 1875, a farmer in New Lots, East New York (Brooklyn), about seven miles from the Lower East Side, discovered the body of a young woman in a corn field. The dead woman “lay on [her] back and the hands and arms, which were frozen stiff, were raised as if to ward off the blows of an assailant,” The New York Times reported the next day. “The face of the girl was covered with blood and her eyes were wide open. The tops of her fingernails penetrated her flesh so tightly her hands were clenched in the agony of death.” A more detailed examination by the coroner revealed that her face and throat had been slashed by a knife, cutting her carotid artery and a piece of her left ear. Searching nearby, the police soon found a cigar-maker’s knife, its blade and handle full of blood, which had been tossed into the corn stalks. The girl had a dark complexion and the Times reporter suggested she could be “taken for an octoroon,” a term then used to describe someone who had one-eighth African American or indigenous ancestry. The coroner also later determined that the dead woman was about five-and-a-half months pregnant.

The police investigation moved quickly. Interviews with a streetcar conductor and passengers on the Broadway-East New York route verified that a young woman who fit the dead woman’s description was seen two days earlier on Sunday late in the afternoon on the streetcar that traveled from the South Seventh Street Ferry. She had gotten off at Howard’s Hotel in East New York, not too far from where her body was found. The conductor noted that the woman had not worn a bonnet or hat, which was at the time an unusual fashion choice. The conductor and several passengers had also told the police that on the same car was a “dark-featured man, apparently a Hebrew” (described in other news reports as a “swarthy Polish Jew”). The woman and this man, who “seemed fidgety,” did not speak or interact, but they did exit the car at the same stop.

Meanwhile, Sarah Alexander’s brother, John, who lived on Essex Street in Brooklyn, grew concerned Sunday evening when Sarah had not returned from visiting her cousins, the Rubensteins—Israel, the patriarch of the family who ran a dry goods shop; his second wife, Hannah (or Anna); her two daughters from her first marriage; and Israel’s children (and one of their spouses), including his son Pesach—who all resided in a tenement house, which Israel owned, on Bayard Street near the corner of Mott Street (the store was located on the main floor and family members and renters lived in the upper sections of the building). The next morning, John Alexander visited the Rubensteins and was told that Sarah had left their place at approximately 4 p.m. on Sunday after helping several of the women prepare for a wedding they attended later that day at a hall on Hester Street. Next, he visited the police headquarters on Mulberry Street to see if she had been arrested, but she had not.

When Sarah still had not shown up later on Monday, John placed a missing persons announcement in what he later described in court as “German papers.” This information was picked up by The Sun, a New York City newspaper that pioneered crime reporting. On Wednesday, Dec. 15, there was a brief notation on the Sun’s front page that “Sarah Alexander, a young Jewess has been missing from her house on Essex Street since Sunday.” It was published two columns over from a longer news story about the discovery of the woman’s body on the New Lots farm. By that morning, the Rubensteins had also read news of the found body and realized the woman had to be Sarah. John soon arrived and they informed him; he agreed with their dire assessment. He immediately proceeded to the Brooklyn morgue, where he the identified the dead woman as his sister Sarah.

According to The Sun’s version of these events (which differed slightly from the one in The New York Times), Israel Rubenstein also visited the Brooklyn police station and identified Sarah as the murder victim. While there and in a supposed anxious state, he related to the police that on the Monday night before Sarah’s body was found his son Pesach had told him he had had a dream that “Sarah was being murdered 10 miles away from New York and she asked me to bury her.” Admittedly, this story is bizarre, even suspicious, but not much more than that.

Upon learning of this development, detectives investigating the murder visited the Rubenstein house. One of the detectives, George Zundt, spoke German and was able to communicate with the primarily Yiddish-speaking family. But it is safe to assume that then and later some of the discussion literally got lost in the translation. The detectives questioned members of the family. Pesach was suffering from tuberculosis, an especially deadly disease in the 19th and early 20th centuries, for which there was no real cure. Several family members and acquaintances later testified that he frequently spit up blood.

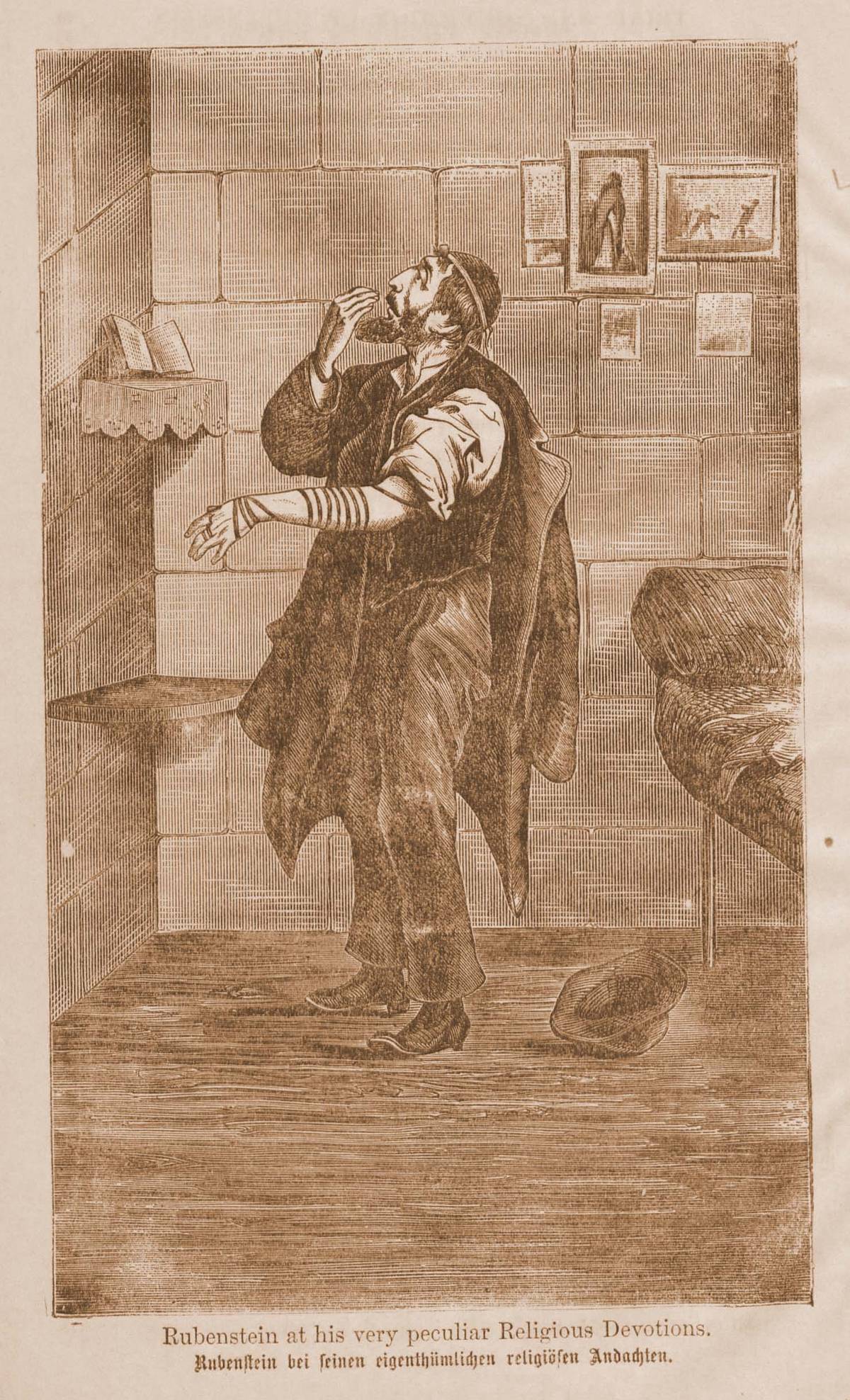

A jewelry peddler, Pesach had immigrated to New York from Poland (under the control of the Russian Empire) in 1873 and lived with his family members, who had been in New York for several years by then. In doing so, he had left his wife behind. Though it was later claimed that he had abandoned her, it was more likely that—as was the case with many Jewish immigrants of this era—he came to New York to raise a sufficient amount of money for her to eventually join him. Pesach was both Orthodox—he attended synagogue for prayer services several times a day—and somewhat odd. Pesach later told the detectives (as translated by Zundt) that he had been out most of Sunday, Dec. 12, visiting with clients, or was at the synagogue. He said that he had seen Sarah earlier in the day when he had briefly returned home to eat something and then he went out again. By the time he got back to the house at 8 p.m., she was gone.

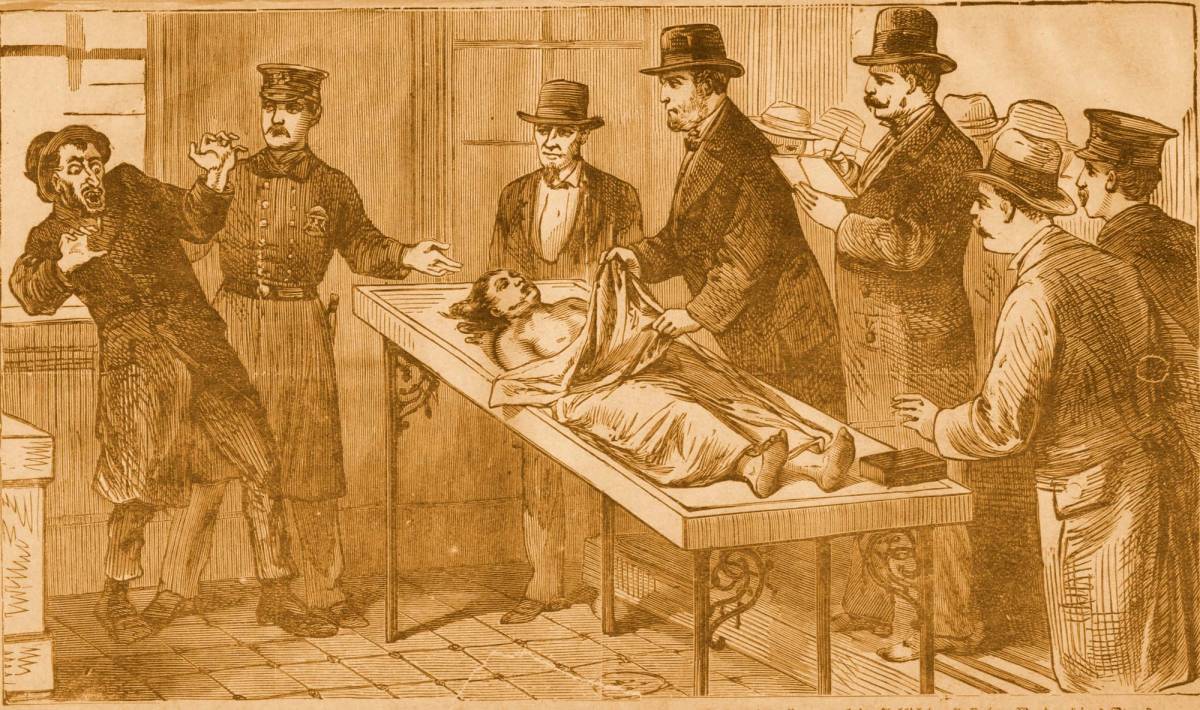

The detectives requested that Pesach accompany them back to the morgue and also identify the body. He was reluctant to do so, but they insisted. Once Pesach saw Sarah lying on a stone slab, he became so agitated and distraught the detectives decided that he had to be the murderer and arrested him.

This can only be called a classic case of tunnel vision. Thereafter, all the evidence and witness testimony the police amassed was shaped to fit their conceived narrative of what had transpired, even if the facts as they understood them were open to question.

The police and district attorney’s version of the events of mid-December 1875, which were presented at Rubenstein’s trial, which began on Jan. 31, 1876, at the County Court House in Brooklyn, was as follows:

Rubenstein and Sarah were alleged to have been involved in an intimate relationship, though there was no actual proof of that. John Alexander did testify that Rubenstein had given Sarah earrings, but he did not know if it was a present between lovers or merely a gift from a jewelry salesman to his younger cousin. Nonetheless, the accusation that he had “seduced” her and that there had been “adulterous intercourse” was immediately accepted as the truth. “Between [Rubenstein] and the deceased woman an intimacy existed which is believed to have been of a criminal character,” declared The New York Times on Dec. 16, without explanation. Presumably the charge of criminality was the soon accepted fact that Rubenstein was the father of Sarah’s unborn child. Yet, there was no evidence of this either, nor was it possible to prove in 1875. Nonetheless, as William Beach, one of Rubenstein’s two lawyers—the other was John Mott, both hired by Rubenstein and his family—argued, the DA “turned the whole force of his investigation upon it … [but] has failed to establish even a suspicion.” In short, added Beach, there was “nothing suggestive of any impure relation between this defendant and the murdered girl.”

The story was that Sarah, who had lived with the Rubenstein’s for about 10 months working as a housemaid, had nursed Pesach back to health and they had become close. But given how strictly religious Rubenstein was, the idea of a woman, whether she was a cousin or not, taking care of him was open to question. John Alexander did believe that Sarah had taken care of Rubenstein, but his memory of the actual circumstances was vague. Other witnesses claimed that two men looked after Rubenstein. And Hannah Rubenstein insisted that Sarah had cared for her while she was sick some months earlier, not Pesach. The DA and police, however, dismissed this statement as they did almost every other fact that countered their narrative of the crime.

Rubenstein, the alleged father of Sarah’s unborn child, had supposedly panicked about the impending birth, given his marital status. About a week before the murder, the 12-year-old daughter of a knife and cutlery dealer on Essex Street swore that she had sold a cigar-maker’s knife like the one found at the crime scene to Rubenstein. Other witnesses testified that the Polish Jew they had seen on the streetcar on the day of the murder, the one who had no communication with Sarah, was Rubenstein. This also was problematic: If it was indeed Rubenstein on the streetcar, how was it possible he and Sarah did not acknowledge or speak to each other during the entire trip?

DA Winchester in his lengthy summation demonstrated his anti-Jewish bias by arguing that the defense team’s alibi witnesses were not to be believed because they were Jews and Jews were ‘clannish’—he used the word three times—and not to be trusted.

Considering that there were many other Eastern European Jews with beards, sidelocks, black hats, and religious garb in New York at the time, it is not impossible that the 12-year-old girl and the witnesses on the streetcar were mistaken; that Rubenstein was not the man who purchased the knife, nor was he the Jewish man on the car. In fact, that person might have been someone else who had nothing to do with the murder. (According to the Los Angeles-based Constitutional Rights Foundation, “studies have shown that mistaken eyewitness testimony accounts for about half of all wrongful convictions. Researchers at Ohio State University examined hundreds of wrongful convictions and determined that roughly 52% of the errors resulted from eyewitness mistakes.” In the late 19th century, when there were no real limits on police power or their interrogation techniques, eyewitness identification was even less reliable than it is today, especially given the unusual circumstances of the Rubenstein case.)

Rubenstein’s trial also featured an early use of forensic science, such as it was in 1876. An analytical chemist testified for the prosecution that spots and fibrous substance found on Rubenstein’s boots were dried blood intermingled with vegetable matter. There were also blood spots found on Rubenstein’s jacket and tzitzit (the fringes worn on traditional garments). Yet there was no DNA or proper blood analysis at the time and the chemist did not know definitively whose blood it was or whether it was human blood or that of an animal. Three days before he was arrested and jailed, Rubenstein walked around the wet and muddy streets of his neighborhood. The blood on the boots could have come from the fish market, slaughterhouse, or from Rubenstein’s visit at the morgue, and the blood on his clothes might have been blood that he spit up, a common ailment of someone with tuberculosis. Much was made of the fact that during the 12-day trial, Rubenstein did not spit up blood into the spittoon that was placed beside him. At the same time, the chemist did not examine Rubenstein’s boots until Jan. 23, 40 days after the murder, making his conclusions moot.

Rubenstein’s defense attorneys presented numerous witnesses who, while not in agreement about Rubenstein’s precise movements on the December Sunday in question, suggested that he was at the synagogue, shopping, visiting clients, or at home on Bayard Street when the murder was supposed to have occurred—just as Pesach himself had initially told the police. All of these witnesses, recently arrived immigrants who mainly spoke Yiddish, were dependent on several court appointed interpreters. While the lengthy transcript of the proceedings is not entirely clear on this issue, most of them, if not all, spoke German, rather than Yiddish. Hence, (as Mia Brett also notes) some parts of their testimony might have been not accurately translated and thus misconstrued. As religious Jews, most of them also could not swear under oath on the Bible with the men having to remove their hats. Though they were allowed to testify by making an affirmation— a solemn declaration to tell the truth—the district attorney later implied that their statements were somehow tainted by their objections to taking the oath the way a non-Jew did.

Rubenstein’s trial came down to which version of the story the jury believed; and there was never truly a doubt that the district attorney’s narrative would win them over. Despite the objections of Rubenstein’s lawyers, DA Winchester in his lengthy summation demonstrated his anti-Jewish bias by arguing that the defense team’s alibi witnesses were not to be believed because they were Jews and Jews were “clannish”—he used the word three times—and not to be trusted; and that many of the key witnesses were members of Rubenstein’s family and hence would have said anything to save him. It was an antisemitic diatribe from start to finish.

“This prisoner belongs to a class of people known as Polish Jews,” Winchester told the jury. “They come from a little place in the Russian dominions, among the conquered provinces of Russia; a class by themselves, peculiar in their characteristics, living in a comparatively small territory they are dirty, ignorant, uncultivated, have no school education, except what is obtained from their religious teachers, they are oppressed and despised by surrounding races. There they are isolated, having their own customs, their own laws, and their own peculiar faith, and as a consequence, they become intensely clannish …Now, gentlemen, do not misunderstand me. I do not apply these remarks to all the people of this or any other country, who have adopted the Jewish or Israelitish faith—far from that. It does not lie in my mouth to condemn a religious people who have accepted as their guide the Old Testament handed down by God Almighty … [But] when these people come to this country they bring the same characteristics which they possessed abroad; they assemble together in some specific locality; they live together, as it were, another people than ours, with different customs and different habits; in the extreme, clannish … [T]hese characteristics of this peculiar class of people … such that they would override other obligations for the protection of one of their own kind, to a degree to which more intelligent and more cultivated men, differently educated, would not assent.”

Rubenstein’s lawyers were outraged and insisted that the judge include a statement in his charge to the jury—which he did—that they “have no right to discredit any witness because of his race or faith as an Israelite, nor because of the manner of the administration of the oath, not because of any prejudice or any reason against that class of citizens.” And if they believed the testimony of the alibi witnesses, regardless of their family connection to the accused, “the defendant cannot properly be convicted.”

It was too late, however. Not only did the jury members accept the DA’s anti-Jewish remarks as being true and relevant, dismissing the alibi witnesses, they were also influenced by Rubenstein’s sickly demeanor—The New York Times described him as “pale, haggard, idiotic, corpse-like, and filthy”— caused by his illness and refusal to eat any nonkosher food provided for him in jail. Their deliberations only took an hour and they delivered a verdict of guilty. “I know nothing about it. I did not commit the crime!” Rubenstein yelled, tugging at his long sidelocks. “I do not want to give up my blood. They may yet discover I am innocent. That is my witness that I never had my hand on any woman—never touch a woman, and that time will found I am innocent, and the jury have made a mistake.” At that, the judge sentenced Rubenstein to be hanged on Friday, March 24, 1876.

Rubenstein was castigated in newspaper stories across the country as the “Jew Murderer.” Pamphlets and booklets soon appeared that detailed the case in the most sordid way possible. Strangers shouted “Rubenstein, Rubenstein” at Jews on the streets of New York and elsewhere. And children sang the song, “My Name is Pesach Rubenstein.” As for the nascent Yiddish press, many of its editors thought Rubenstein “was totally nuts,” as historian Eddy Portnoy writes.

Prison officials at the Raymond Street Jail in Brooklyn would not permit Rubenstein’s family to bring him any food because they believed they would attempt to poison him so that he could commit suicide and evade his hanging. Eventually, they allowed Rubenstein to cook his own food, closely monitoring him as he used a gas stove to do so. But his illness and debilitating state worsened amid the “noisome atmosphere of a cell which was full of filth and swarming with vermin,” as The New York Times described it. He prayed all day and night exhibiting behavior his jailers and other prisoners considered bizarre.

Urged on by members of the family, Rubenstein’s lawyers filed a motion for a stay of proceedings to delay the execution until a proper appeal could be made within a few months. This was ultimately granted so the hanging was delayed. Yet it was only a temporary reprieve and on May 8, Rubenstein was told that a final decision of his fate was to be made soon. That evening, Rubenstein had a seizure and died. He had avoided the gallows.

Whether or not Pesach Rubenstein rightly deserved to be on death row in the first place remains a matter of contention. He was arguably discriminated against and even victimized by Brooklyn police and justice officials and found guilty of the murder of his cousin Sarah Alexander based on circumstantial evidence and witness testimony, which at the very least raised reasonable doubts of his culpability.

Historian and writer Allan Levine’s most recent book is Details Are Unprintable: Wayne Lonergan and the Sensational Café Society Murder.