Politics and the Yeshivish Language

For the sake of Jewry, the Orthodox should give up their private dialect

The summer after our junior year at our pluralistic Jewish high school near Washington, D.C., my stepbrother and I spent two weeks at Yale with 35 or so modern Orthodox peers. The program we attended taught the works of C.S. Lewis and Joseph Soloveitchik, and I was eager, for the first time in my life, to meet serious Orthodox people my age. Which I did. But we had a language problem.

These kids from Teaneck, Long Island, and Boston, learned in subjects Jewish and general, spoke (a mild form of) what sociolinguists call Yeshivish, an Aramaic/Yiddish/Hebrew-infused dialect of English used by many Orthodox Americans. When speaking with me, my new friends were OK—but not great—at using only standard English. And to their credit, they graciously answered questions like, “Dovid, what does al achas kama v’kama mean?” or “What is the Triangle K, and why wouldn’t someone—what’d that guy say—hold by it?” or “Can just anyone bavorn?” But all the same, my decade of Hebrew study, my lifelong attendance at an old-school Conservative synagogue, and my charitable disposition toward Orthodoxy couldn’t thwart the belief that my peers’ very vibrant religion was also downright bizarre. It was a religion I got only in translation.

I was the lonely man of faithlessness, frustrated by an in-speak that kept me out, even though nobody was actually trying to keep me out. After one alienating day I demanded an explanation from one of the program’s faculty, Meir Soloveichik, the noted Orthodox rabbi who leads Congregation Shearith Israel in Manhattan. “Why would you go in for this religion?” I asked. He replied: “Because it’s true.”

Because it’s true. This was something novel, and for somebody not yet Orthodox, something of a problem. The content and form of Soloveichik’s statement—he and the other faculty always spoke to me in 18-karat English—denied that Judaism was esoteric or secret, and that denial invited me to join him and my peers in the community of faith. Performed by my peers, Orthodoxy was very cool but very much not mine— offered in my mother tongue, as Soloveichik did then and after, I could now understand it, and so had to reject or to accept it.

I ended up accepting, but the linguistic stumbling block I had to overcome stops many people from having the choice. Soloveichik is one of the few Orthodox personages nowadays whose speeches and essays about Judaism can be understood by anyone with a good command of standard English. Jonathan Sacks was of course the master in this respect, and he enlightened millions of Jews, and tens of millions of gentiles, about the claims of Judaism. Norman Lamm. Erica Brown, too. The list is short. I haven’t heard more than a dozen sermons in Orthodox synagogues that would qualify (Soloveichik’s aside). Peruse Yeshiva University’s audio archive, and try to find a lecture that a secular Jew with a university but no Jewish education could follow. Orthodox Judaism—which I believe in, practice, and love, and which I think every Jew has an obligation to believe in, practice, and love—has cordoned itself off from 5 million American Jews. And the most potent instrument of this auto-segregation is Yeshivish, the language in which so much Orthodox life is conducted.

Yeshivish is, simply put, “one more of the language varieties Jews have created based on the language of their nation in residence,” writes John McWhorter, the Columbia linguist. Yiddish grew from a Jewish German, Ladino from a Jewish Spanish; Bukharan Jews speak a kind of Jewish Persian. “Languages coming together is a default,” McWhorter writes. Four melded to make Yeshivish: English provides the grammar and much of the vocabulary. Yiddish, the vernacular of most Ashkenazi Jews in Europe, is the largest non-English source of words. Next is Hebrew, the language of sacred Jewish texts, excepting the Talmud, which was composed in Aramaic—the fourth influence—and which is studied by the most conspicuous group of Yeshivish speakers: Yeshiva students (bochrim) and their teachers (rebbeim).

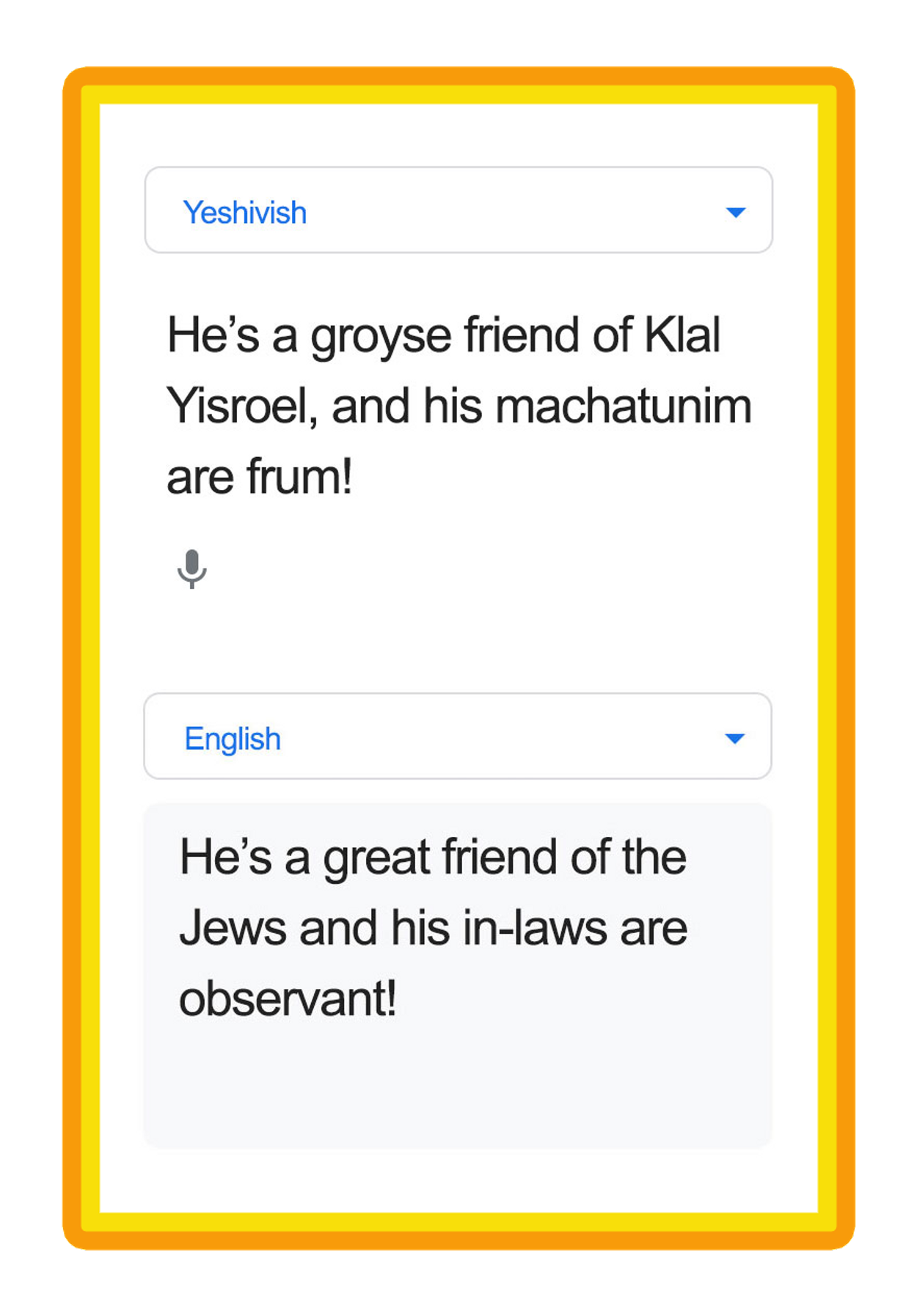

Like Hebrew for Israeli Jews, Yeshivish is both a sacred and a secular language, and its content varies by group and by context. Hasidic enclaves use more Yiddish in their Yeshivish. As a friend of mine points out to me, men as a rule speak with more Aramaic than women, because in many communities women don’t study Talmud. The Teaneck, New Jersey, variant is tamer—more comprehensible to most Americans—than that of Kew Gardens Hills, Queens, which is again milder than what’s spoken in Lakewood, New Jersey. Sometimes the foreignness of Yeshivish manifests in isolated nouns and adjectives: “Sheyfele, behave yourselves, or Tati will give you a patsh,” a mother might admonish her children in a park. Then there’s the ubiquitous “by,” an import from Yiddish (and before that, German) that replaces numerous prepositions in standard English, as in: “I heard by the shmorg that the kallah got her sheitl by Shevy’s. Shpitz!”—or, as we might say, “I heard over hors d’oeuvres that the bride bought her wig at Eliza’s. Very ritzy!” Sometimes the non-English element is thicker. Here is a defense of Donald Trump’s sanity: “M’heicha teisi are you noyteh to say that Trump has a dibbuk? He’s a groyse friend of Klal Yisroel, and his machatunim are frum!” (“Why are you inclined to say that Trump is a lunatic? He’s a great friend of the Jews and his in-laws are observant.”)

And in religious contexts, prepositions and articles and suffixes are often the only signs the speaker knows English. “L’maskanah Raboysai, the Mishneh Torah is takeh mechaleik between stam eidus mukcheshes, which is mevatel the cheftzah shel eidus, and eidim zoymemin, who are tokeif the gavra eidim, mamash the kat!” Roughly speaking, that means, “Gentlemen, in conclusion: Maimonides’ Code distinguishes between conflicting testimonies, which simply cancel each other out, and witnesses who accuse other witnesses of conspiratorial perjury, thus attacking their very credibility as people.”

This is all very interesting for the lexicographically or linguistically minded, and I can recommend to you Chaim Weiser’s Frumspeak, the first dictionary of Yeshivish, and Sarah Bunin Benor’s Becoming Frum, on Orthodox life and language. But what I want to ask now is whether this is the way things ought to be. Judaism, the religion itself, is a severe dogma and way of life. Its liturgy and texts are in Hebrew, which I myself knew well enough when I became Orthodox but which is foreign to most American Jews. To add on top of this a hybridized communal dialect—well, let me put it this way: If you were trying to make Orthodox Judaism inaccessible, what would you do differently?

Yeshivish doesn’t trouble me for ideological reasons. I don’t have some stodgy, Ivy League devotion to “pure” English, because there is no such thing. Nor do I think Orthodox Jews should be like other Americans—Jewish difference is Jewish strength. And it’s not that I don’t love Hebrew, Aramaic, and Yiddish—I know the first, I read the second, and as for the third, well, I hope she’ll teach me, whoever she is.

No, I’m against Yeshivish because it hinders an urgent task of Orthodox Jews in this country: restoring to the Lord’s covenant our rapidly assimilating brethren. The math is just brutal. According to projections by Edieal Pinker of the Yale School of Management, the Reform and Conservative movements will shrink by a million members over the next 40 years. Those who remain will mostly be older; the younger will be very likely to intermarry. Perhaps the terror of anonymity or perhaps a Jewish catastrophe will awaken millions of Jews who, however they identify, right now simply do not act as though Jewish continuity outranks their pursuit of American happiness. Perhaps. But there is a third option: the largest recruitment effort in Jewish history, commanded and staffed from Orthodox enclaves.

Orthodox Jews have the material resources, the institutional know-how, and above all the love of God and of Torah needed for such a mission. But if we want to reverse American Jewry’s self-mortification, Orthodox Jews will need to scotch their smug pity for liberal Jews—Orthodox folks, please do not pretend not to know what I’m talking about—in favor of evangelical zeal and religious fluency in English, the only language common to American Jews.

Most Americans Jews don’t know a chumra from a kula. HaKadosh Baruch Hu and the Ribbono Shel Olam are as alien to them as sushi was to the shtetl. Avraham Avinu, Sarah Imeinu, Dovid Ha’Melech, Esther HaMalka, the Gra, the Grach, the Rov, the Rav, the Rebbe—these are the heroes of Jewish history, but naming them as I’ve done (rather than as “Abraham,” “Sarah,” etc.) puts that history on a shelf marked “not for you.” Anywhere a non-Orthodox Jew might be listening in—an office, a college dining hall, and many more synagogues than you’d think—is a place where a small change in language can invite someone toward Judaism instead of repelling her from it.

“But you sound so goyish!” a very scholarly friend of mine said to me about an article I’d just written. He did not mean to censure; even though he agreed with my article, its diction was foreign to the Yiddishkeit—the sacred Jewish canopy—in which his parents raised him and in which he raises his own children. I sympathize with this knee-jerk linguistic tribalism—sort of. Militating against it is the chance to save someone’s Jewish identity by just getting over your squeamishness about sounding like a gentile. Such squeamishness should be heeded when it protects a thing of value, ignored when it attacks a thing of value.

But perhaps talking like this (to adapt a phrase of McWhorter’s) is a thing of serious value indeed? As two other friends, one ultra-Orthodox, the other traditional and egalitarian, conveyed to me: “Ima and Abba taught me Torah in these words and not in other words. I pray to Hashem, not to the Almighty—and by the way I don’t pray, I daven. I don’t know from Moses—at my Pesach Seder, we hear about Moshe Rabbeinu. Bubby and Zayde spoke Yiddish and now in America we speak this. Moreover: Yeshivish inoculates Orthodox Jews against assimilation—whenever they open their mouths, they’re reminded they’re different. The very public complaints of refugees from the right wing of Orthodoxy about poor English education? That’s the price of religious life in a country looking to love Jews to demographic death.”

Cultural in-speak does have its functions. And it’s not just cultures—families, friends, and married couples often can’t be fully understood by outsiders. And that’s a good thing. Semiprivate languages express the special regard we have for certain people, the gratitude for our common form of life. The richest goods—marriage, parenthood, friendship, country—cannot exist unless some people are in and others are out. The relationship between man and God is the most particular of all: God is jealous, demanding total fealty from creatures on each of whom He has stamped an unreproducible image of Himself. We do not talk to or about God as we talk about others. To do otherwise is idolatrous. In a similar vein: To sacrifice a Jewish way of talking for a gentile one—we wouldn’t know ourselves.

But let me ask something. Who’s we? I think the proper referent of we is all the Jews. We’re a family. Christians are content to live each among his own countrymen, united by a creed professed in hundreds of local vernaculars. Jews are bound to each other by blood and by faith, each Jew the guarantor of every other. I once asked a Chabad rabbi how the Lubavitcher Rebbe got thousands of couples to go all over the world. This rabbi told me he once heard the Rebbe speaking to a group of these couples about to get on a plane: See that man in the suit with the briefcase and no yarmulke? the Rebbe said. That’s your brother. The woman who doesn’t know her grandmother spoke a gorgeous Yiddish? That’s your sister. Many of our brothers and sisters do not know our words. Most of them will not learn ours unless we first learn theirs. Not to do so, not to speak Jewishly in English, is malign neglect.

But is speaking standard English self-sabotage? If Jewish children talk like gentiles they’ll become more like gentiles, won’t they? Here’s my proposal: communal bilingualism. Not in Yeshivish and in English, but in English and in Hebrew. To our shame do so many Orthodox Jews speak bad Hebrew. Hebrew is the language of Jewish texts and the language of Israel, the world’s largest Jewish community. If American Orthodox Jews want to be Jewish in a Jewish language, Hebrew is it, as a matter of religious obligation and national solidarity. But for those of us who remain in America, we have duties to Jews who, through no fault of their own, were raised far from faith. Besides, as a matter of professional necessity, most Orthodox Jews need to know English anyhow. I’m proposing an expanded vocabulary for the sake of a good, I might say holy, cause.

For unsung exemplars in Yeshivish World, look to those who do professional kiruv—internal Jewish recruitment, from the Hebrew word for “closeness.” Those working for AISH, Chabad, Meor and the like have to be Jewishly fluent in English or they can’t do their jobs. But their jobs are our jobs, too: ensuring all Jews see themselves and act as part of our covenantal destiny.

I know what it’s like to trade old thoughts, clothes, friends, ways, and words for new ones. It’s like jogging on a winter day: The only way to warm up is to go fast, but go too fast and you’ll pass out. It’s an astonishing thing that God asked of Abraham—leave the place of your birth for the land that I will show you. Nowadays, so far as we know, God doesn’t issue many personalized invitations; He’s left that task to human beings. Invitations should be tailored to invitees, especially when the adventure itself is so strange and strict. I believe with all my heart that this adventure, the Jewish covenant with God, is true and redemptive, the source of meaning and love in an otherwise cold cosmos. If you agree with me, do everything in your power to share it with others—in words that might be new to you, but which those listening to you will understand, and so cannot possibly ignore.

Cole S. Aronson resides in Eli, Israel, and is writing a defense of traditional Judaism.