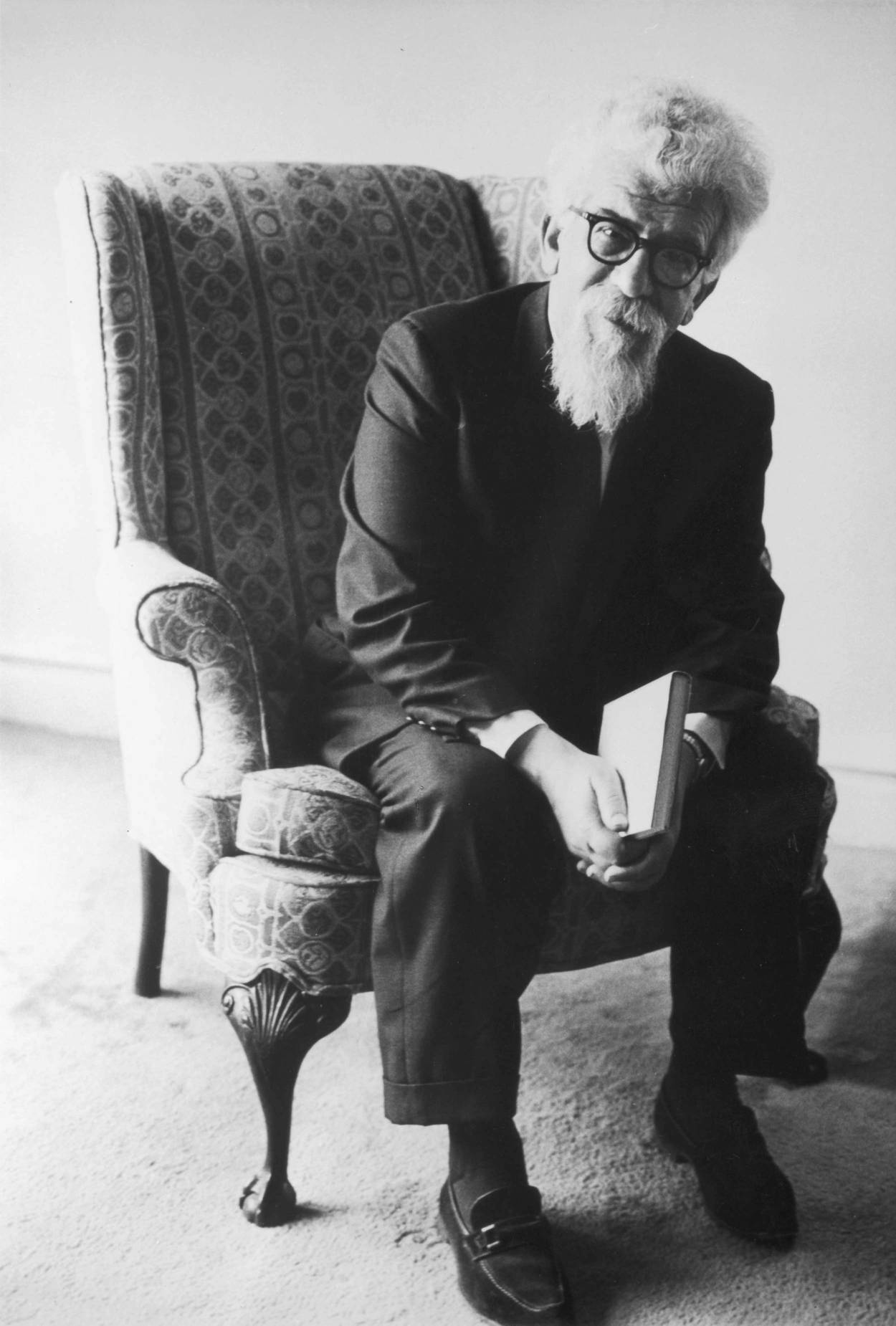

Profound and Pious

Decoding what made Abraham Joshua Heschel such a complicated and unique man—in the Jewish world, American culture, and our family—50 years after his death

In the summer of 1959, my newlywed parents—who resembled the sun-dappled, giggling couple running on the Brooklyn Bridge in the famous Norman Parkinson photo of that year—walked over a few blocks from their upper West Side apartment to eat shaleshudes, the third Sabbath meal, with my mother’s cousin on Riverside Drive. In the family, this cousin was referred to as “the Professor”—Abraham Joshua Heschel, of the Jewish Theological Seminary.

My father, a newly minted rabbi himself, righteously mad for God, his red hair on fire, his white skin the color of parchment; my mother, translucent, green-eyed, innocent and a scion of a distinguished Hasidic family. My parents had to know who Heschel was outside the family. Though he had yet to achieve the pinnacle of fame he would reach in the 1960s, he was already distinguished for his writings by the time of my parents’ visit. His masterworks, The Earth is the Lord’s, The Sabbath, and God In Search of Man, were published in the early 1950s, along with a Yiddish paean to the lost world of Hasidic spirituality in Eastern Europe, and in 1956 Time magazine ran a feature on him with a photo.

One wonders, then, what was discussed at this meeting between my father and my mother and the Heschels: The future of Judaism? What will become of Orthodoxy or chassidus in America? Perhaps, but unlikely.

Instead, they drank tea, had compote or fruit salad or sponge cake, and made small talk. How was dos shvesterkind Shifra, (my mother’s mother was Heschel’s cousin) and vos macht dos shvesterkind Avrom (Abraham Twersky, my mother’s father, was also a cousin), and Sure’le, one of my grandmother’s sisters. Relatives both dead and alive remained bright to Heschel like moons ringed around a planet. In fact, he knew the lineage by heart—250 family members—even those who died in the camps and even those going back centuries. How was Louis Finkelstein, chancellor at the seminary? He treats you ganz fein? my father asked. (My father had received ordination there a few years earlier, but then converted to the religious high heat of Yeshiva Chaim Berlin where he received a second ordination.) Such was the chatter from a casual visit among relatives, near totally buried by the sands of time until one day nearly 40 years later.

Naturally, we had Heschel’s books in our house and as a young man I started to read them. I don’t know whether it was these passages or something else that I came across then, but he had unusual things to say. Things that were different from what I heard from other rabbis: Man is not in search of God. God is in search of Man. It wasn’t God who disappointed at Auschwitz; it was man who disappointed God. Not the victims, of course, but the powers that be: According to Heschel, God looked for man in that dark time and could not find him. Humanity failed to live up to our potential as moral beings capable of love and self-sacrifice, or at least to safeguard the holy human covenant with the sacred soul and the spirit.

That God was in search of man, that there was something in us, something holy or even significant that we might “offer,” was a shocking notion to me. I was steeped in the religiously hierarchical world of a certain kind of Orthodox Judaism in which man was seen as an inherently corrupt entity and that our only hope was to receive from those greater than us—the more we could be like them, the better. “We,” as it were, had nothing to offer.

But Heschel went further: He decried contemporary American Judaism—Orthodox, Hasidic, Reform, and Conservative, all of which he called “love by habit” worship by discipline, formulaic and meaningless, focused on the splendor of the past with no understanding for the present—a religion overly worshipful of its past that speaks with an empty authority and an unintelligent compassion.

Heschel’s words tore through me in a way that made me deeply uncomfortable, but I knew he was right. All that time I spent in shul it felt rote and he had the courage to say it.

“Who is this Heschel,” I asked my father. Is he oysgehaltn—of good standing, theologically speaking?

“Heschel is our cousin.”

“You know him?”

“Yes, but I will tell you something modne [strange] from when we visited him years ago …” And he told me about what had transpired during that Sabbath meal back in 1959.

In the courtyard of the building, my father told me, Heschel doted on his young daughter, Chana Shoshana (now known as Susannah), who rode a red bicycle on the Sabbath.

“Kh’hob af im gekukt,” I looked at him, my father said. “How did he allow Susannah to ride the bicycle without an eruv, seemingly a transgression of the Sabbath? After all, Heschel had written the book on the sanctity of the Sabbath!”

Of course, even my father, mad for God in those days, a firebrand from Yeshiva Chaim Berlin knew that the bone he chose to pick was obsessive by any standard, even for a halachist such as he. After all, Susannah was a mere child of 7 years old and besides, the courtyard did not require an eruv; it was permissible to ride according to some halachic authorities.

In any case, my father told me he was silent during the Sabbath visit. We were a family of soft hands and velvet rebukes. Nevertheless, a light tension fell over the shaleshudes like a dusting of snow. In such rarefied circles, however, even the most silent rebukes make a little noise. The disquiet hovered through the decades and bumped up again in my father’s retelling.

(A few years ago, I spoke with Susannah and told her of my parents’ visit and her red bicycle. “That’s amazing,” she told me. “I did have a red bicycle then. It must have been with training wheels.”)

As my father tells it, Heschel responded to his silent rebuke with a touch of holy slyness. As if to say, s’du teruzim a sach, I’m no am haaretz, ignoramus. I have many possible answers for you …

By my father’s lights, he had brought the icon down to earth for me with this vignette. Inadvertently, however, he had actually conveyed to me something about Heschel’s greatness that I could only understand much, much later in life.

Heschel, whose father had died when he was 10, had grown up in the house of my great-grandfather, the rebbe of Novominsk, who was his maternal uncle. Reb Alter Yisrael Shimon Perlow, the Tiferes Ish, as he was called, was among the most ascetic, pious, and monkish men of Warsaw. Heschel ate shaleshudes at his table often on Franciszkanka Street in Poland’s capital in the Jewish district. Two other Warsaw luminaries, Hillel Zeitlin and Fischel Schneerson, occasionally joined the Novominsker for the third Sabbath meal.

Along with purity of soul and an ocean of knowledge, the Novominsker transmitted the heroic tradition of the Baal Shem Tov, whose love for the word of God was tempered by his compassion for the “human cause,” as well as the tradition of Reb Menachem Mendel Morgenstern of Kotzk, heir to harsh pieties and the pursuit of truth. He was definitely not the rebbe for the everyman. It was well-known that his absolute standards could be destructive to the “average” person, who had to be shielded from his bright light.

A half-century after Heschel’s passing—50 years ago this week—people ask how Heschel, only a month after arriving in the States as a refugee, had the audacity to confront Albert Einstein over his lack of belief in a personal god, the Pentagon over Vietnam, and the pope over the Vatican’s doctrine of Jewish deicide, all while marching with Martin Luther King at Selma and pushing for gender equality in Jewish ritual?

The Kotzker rebbe once said that the trodden path is for horses. A man must not imitate another man, but be himself. But if he believes in himself only, he is worthless. Heschel once quipped that the Baal Shem Tov gave him a sense of religious and human possibility, while the Kotzker gave him the sense of humility that properly centered and chastened him.

While these influences on Heschel are obvious, I have come to understand that if you want to really learn about a man, find out about the women in his life and study the woman he did not marry as opposed to the one he did. Bearing that in mind, here is something very interesting: At the age of 18, he was “supposed” to have married my grandmother Shifra’s beautiful sister Gitel—and there were many reasons such a match would have been compelling, but he demurred. For this there were many reasons, but my own sense is that he was hungry to accomplish in the world and he could not give his heart and soul to the cloistered milieu of Novominsk despite its holiness and warmth.

He may have saved his life.

Novominsk was poor, as was Heschel’s own father. Poverty seared and scarred my grandmother’s family, but it also had great meaning. It was a fact of life that would certainly have been consciously avoided, but religiously speaking, it was also a call to piously identify with a god in exile and to minister to His people, particularly the downtrodden and the oppressed.

For example, Heschel’s own father chose to set up a shtibel, a humble house of prayer, in the poorest district of Warsaw. In the house of Novominsk, if there was any money left in the evening it would not be kept overnight; it was the custom among some of the Polish rebbes to give it all to the poor. Perhaps this was where Heschel’s sense of identification with the poor and dispossessed originated.

In any case, Heschel’s hunger to study philosophy, art, history, and literature was immense. Small amounts of money were obtained somehow that sustained his tutors in Warsaw for a short time, yet there was an economic collapse in Poland between the wars and the money ran completely dry.

The following story may be apocryphal, but in my own sense, it has a plausible aspect: Heschel had a friend named Yitzchak Meir Levin, a merchant and follower of Kotzk who prayed on Sabbath at the Heschel family shtibel, house of prayer. He had heard about Heschel’s money problems and saw that he was deeply despondent. To cheer him up, Levin told Heschel about a new book he bought that expanded on the Hasidic teachings of Heschel’s ancestor, Reb Pinchas of Koretz. Heschel perked up a bit. On Sabbath morning, Levin brought Heschel the book.

My grandfather had told me that there was an eruv in Warsaw before the war, which permitted carrying, but the pious men of Ger, Kotzk, and Novominsk did not use it. So it was already a surprise that Levin had carried the precious book from his home, but a more massive shock was yet to come. Heschel opened the book and to his horror, it contained money, which Jews were forbidden to touch on the Sabbath. Heschel put the book down at once.

Seeing Heschel’s shock, Levin explained something on the order that it was permitted to commit a minor sin against the Sabbath (muktzeh) to save Heschel’s life. Sadness born of hopelessness—ye’ush, as a Kotzker would have said it—not only contains no holiness but is a gateway to sin and moral collapse.

To bend the rules for God or for the sake of something noble—this break with normative Halacha paradoxically enabled Heschel to remain devout for the rest of his life. To have made room within the rigidity of Jewish law for a spiritual audacity fortified Heschel’s faith even as he engaged dramatically and intimately with the secular world.

In 1925, after much reflection, Heschel decided to leave Warsaw and study in Vilna. It is not known how the Novominsker rebbe really felt or said about it, but he warned him, “do not become polluted by the world.”

And so he went out into the world, wearing a borrowed coat and a vochendik weekday everyman’s cap on a Saturday night train from Warsaw to Vilna. The train moved mournfully in the nepildeke nacht, a soupy, Ingmar Bergmanesque darkness from Warsaw to Bialystok to Mackava to Kovno to Vilna, the foreboding of cold steel on cold steel. Shtel zikh fohr—imagine what unbearable pressure this young man must have felt!

To me, it is unimaginable that Heschel, who later became the ultimate humanist, would not be allowed to pursue his studies, to be human, to be “normal.” It is head-splitting!

Probably because of the burden the rebbe placed on him, he remained austere, even monkish—ever the student or professor. He was a composite figure, a scion of noble Hasidic and Lithuanian dynasties, a holder of smicha (ordination) from Reb Menachem Ziemba, the greatest Talmudist of Warsaw, a poet in a borrowed language who was fluent in the world of both Halacha and Aggada. Though he could take in the pleasures of life and art and music, idleness would never be tolerated. In fact, it was only the lure of more learning that led him to study in Berlin.

As the storm of genocide gathered in Germany, Heschel might have wrapped himself in insular piety, but instead he wrote pamphlets for German Jews that drew on the writings of the Baal Shem Tov: Do not fall to indifference, he cautioned. God Himself was in exile, imprisoned. God’s face is in hiding—man himself must act against the radical evil of Nazism. This dramatic event of Evil is also an opportunity to find God. As was often the case, it was a gentile who was captivated by his words. The German Quaker leader Rudolf Schlosser, at great personal risk, distributed copies of his pamphlets in Germany.

On Oct. 28, 1938, Heschel was visited by two Gestapo agents and deported to the Polish border. After spending time in a stateless no man’s land between Germany and Poland, miraculously, he was able to escape to the United States. He was first on the faculty of Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati, but for a Hasidic Jew, the cultural gap was too great there—the rabbinical students barely knew Hebrew, the kitchen was not kosher, there was no daily minyan. Heschel had to bear what he knew: that his mother and sisters, family and friends were being annihilated in the Warsaw Ghetto and American Jewry was totally indifferent. Heschel was appalled and in agony. Just after the war, he was invited to teach at the Jewish Theological Seminary, where there were several rabbinic luminaries, refugees of the old world, and he accepted.

He was initially not popular as a professor—he was considered meandering, disorganized—but he had been assigned to the Teacher’s Institute to students who had no interest or capability to understand what he had to offer. (He was not allowed at first to teach in the rabbinic program.) Ironically, this very mismatch turned him inward and helped him to synthesize his central ideas. A holy opportunist, like the rebbes, he stumbled upon an idea: The moral crimes perpetrated by Germany and the world on the brink of nuclear catastrophe were “evidence” sufficient to repudiate the moral relativism, the notion that “all ideas are equal,” that was rampant in prewar Europe. Instead, he came to develop a notion that the living God of the Bible and the prophets represent an absolute standard of morals. Namely, that every human individual was the image of the Divine—and that contact with the Divine was available no, obligatory for Jew and gentile alike through prayer.

This audacious Hasidic man would later prevail upon the pope in the Vatican to condemn antisemitism and to stop missionizing Jews, and meet with Robert McNamara at the Pentagon and with Henry Kissinger at the White House to plead dramatically and unsuccessfully to end the American bombing of civilians in Vietnam. (McNamara held a respectful but indifferent silence; Kissinger paid lip service.) And still later, he marched in Selma with Martin Luther King. He was a man who only a few weeks after his arrival in the United States had the audacity at a conference to challenge Albert Einstein, who, right after the war, had implored Jews to give up on the idea of a personal god. Heschel wrote in his rebuttal pamphlet that all morals must come from God; religion, not science, must answer the question why there is a world and why we live. Somehow, he (and only he) had to be both the good son and a great man—to be both profound on the world stage and pious among his peers, ever-faithful to the “four cubits of Jewish law.”

This kind of pressure to be an ambassador if not a prophet, to speak with the kings and queens, the dictators and the powers of the world at the Vatican, the Pentagon, the White House, and elsewhere, and yet to step aside when it was time to daven mincha or maariv, can (but not necessarily) produce an emotional dissociation sufficient to make someone into a hypocrite or even a sociopath, but in Heschel this tension sparked a dynamism, an unrelenting effort to fuse the modern world and the world of his fathers.

One wonders what role this might have played with the woman he did marry, an American concert pianist named Sylvia Straus, with whom he had become acquainted briefly several years before in Ohio. Heschel was already 39, his identity and ideas firmly formed, when Sylvia had come to New York to study with the pianist Edward Steuermann upon the recommendation of the virtuoso Arthur Rubinstein, and they renewed their connection. In view of his background steeped in chassidus, it was a surprising choice. Their Jewish backgrounds were profoundly different even as they valued each other’s pursuits and accomplishments.

Even during his early years in America, at Hebrew Union College, where the food wasn’t even kosher, he made a shaleshudes of his own for a small group of followers. He would sing the songs of my great-grandfather until the stars came out.

The ebbing moments of Sabbath in chassidus are the moments of dvekus—the height of one-ness with God for the pious. One ends the day with melancholy song to witness as it were, the “death” of the Sabbath. Heschel once wrote that for the pious, death itself is a kind of privilege.

The men in my mother’s family were highly articulate, voluble, garrulous, and learned, but what you got from them you didn’t get from their words, but from their sighs and their songs. My grandfather, Rabbi Twersky, when he spoke of the war, his parents, the relatives, his wife, the whole Jewish enterprise, our significant dead … he would let out a sigh that entered deep into me.

To read of Heschel’s works and his accomplishments, however carefully and reverently, would be to miss his essence. When his efforts on Vietnam and civil rights were defeated, he would let out a sigh—a sigh that might have been more precious than all of the prayers in the world.

As a great-grandson of Heschel’s uncle and mystical mentor, I was stupefied by how in the span of two and a half decades Rabbi Heschel traveled from the mystical but parochial setting of the Tiferes Ish to l’havdil, Martin Luther King, the pope, and the center of the world stage.

My grandmother Shifra told me of her father that he was b’heiligt, holy even in his own house. The children stood up for him every time he entered the room and spoke to him in the third person. They were close but not intimate. Others from Warsaw had told me that he was removed from this world, immersed in piety and Kabbalah, almost oblivious of his own body.

Yet, even as I was born in the 1960s in Atlanta, before I knew anything about Heschel, I was captivated by Martin Luther King. Social activism was not at all the focus of my parents’ interest, yet I became enraptured. My illustrious relative Heschel shared with King oratory and command of Scripture (in Heschel’s case, Torah) and a profound ability to invoke moral authority directly from the prophets.

Is it possible that there might have been something in the Tiferes Ish, however ascetic as he was, that might have allowed even in the crucible of tribal exclusivity with the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, a spark that bonded with all humanity and creation?

What were the words or the vibrations at the shaleshudes in 1920s and ’30s Warsaw? The rebbe had a special niggun, a song exclusively for the third meal, that he himself composed. (There are only one or two people who know it today.) One imagines that with Heschel, Zeitlin, and Fischel Schneerson around him, he would enter another realm, but curiously, he kept a pocket watch at the prayer stand. He always had to be aware of what time it was. It is tempting to fantasize that he sensed something of our future—of Heschel’s, and mine—and being Jewish in America, our new home.

The train ride from Warsaw to Vilna was an eight-hour trip. On the way there, the young Heschel wore a weekday cap and modern clothes. When he returned for frequent visits home, he wore a shabbes hat and Hasidic garb. He would make the round trip between modernity and chassidus throughout his life, sometimes successfully, sometimes less so—as the gap was great. In the end, Heschel was himself. An exemplary life of unparalleled achievement: a profound Jew and a pious one.

Alter Yisrael Shimon Feuerman, a psychotherapist in New Jersey, is director of The New Center for Advanced Psychotherapy Studies. He is also author of the Yiddish novel Yankel and Leah.