Putting Out the Unwelcome Mat

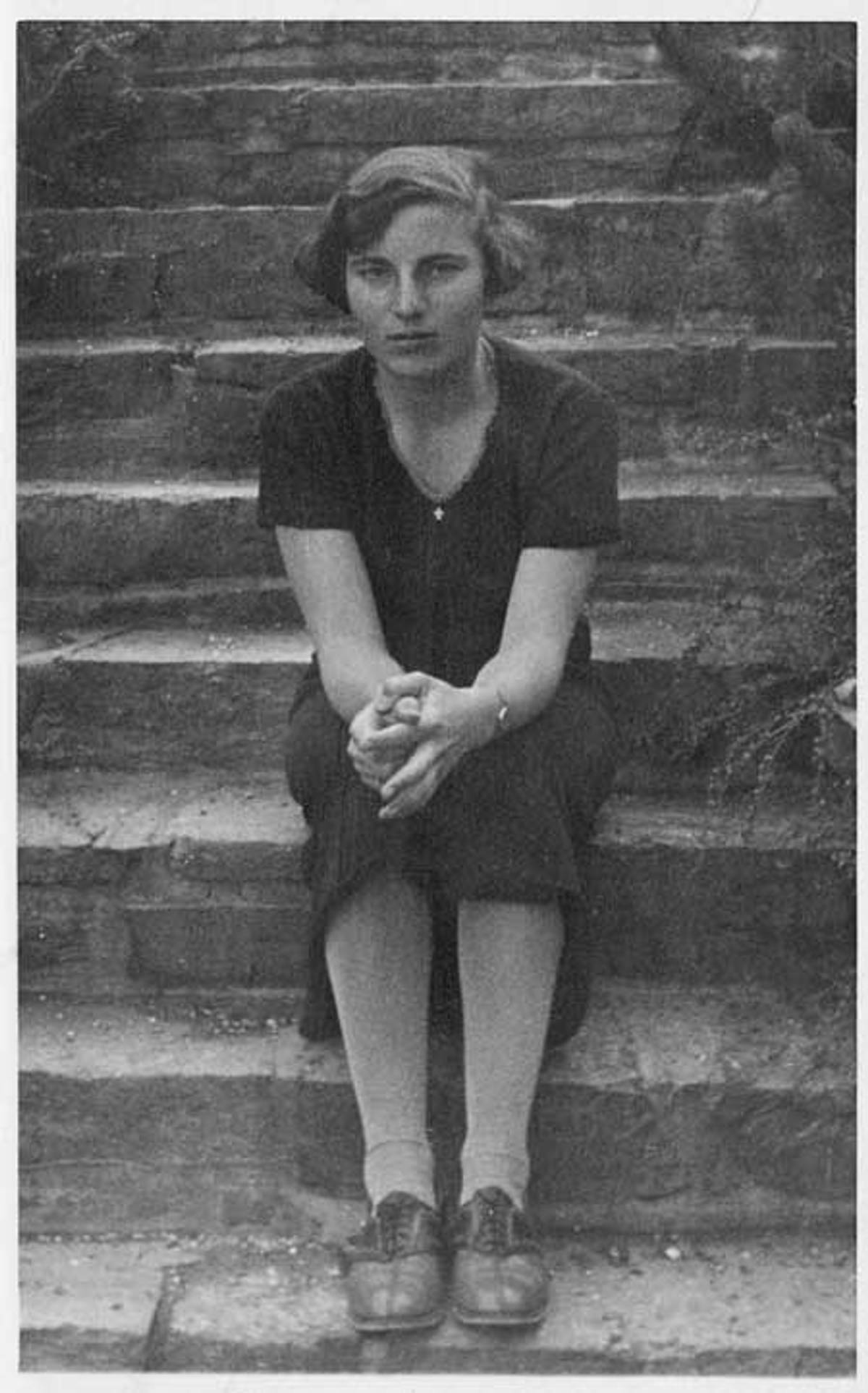

As we turn away refugees, I’m reminded of my mother’s experience trying to enter England from Nazi Germany—and the lifelong scars left by a customs official’s callous rejection

In 1934, when she was 15, my mother, Liesel Weil, was finally forced to leave the excellent Gymnasium (high school) in Frankfurt where she was an assiduous and popular student. This compulsory end to her education had been in sight for a while, as the school officials chose to ignore Nazi decrees forbidding Jews to attend school for as long as they dared. She took a job in a factory—mind-deadening work that she dreaded and that did not leave her enough energy to keep studying on her own. After some six months of this miserable work, she was able to take a break and journey to England to visit her Aunt Daisy.

Tired and chilled after a long journey on a ferry, she found herself facing a British customs official who took one look at her passport and declared: “Your visa is for two weeks. If you stay here a second longer, we’ll put you in a deportation camp and ship you right back where you came from.”

Giving him as hard a look as she could muster, she said: “I have no intention of staying longer, thank you very much! With a welcome like that, I don’t know why you think anyone would want to stay here.”

***

My mother was born in Frankfurt-Am-Mein in 1919 to a well-to-do Jewish family living in a large house in the finest part of the city. Her father owned a clothing factory; her mother’s family connection to the area dated back to the 15th century; her parents’ wedding was officiated by Rabbi Caesar Seligmann, the leader of Liberal Judaism in Germany. Her early life was one of comfort and ease, until the rise of Nazism. After she returned from her brief visit to Aunt Daisy, she began to seek ways to leave her country permanently, aware of the increasingly oppressive measures being taken against people like her by an odious regime.

She was eventually able to immigrate to South Africa, a long journey on her own for a 17-year-old girl with just a suitcase and the equivalent of a few dollars, all the German officials allowed her to take. She was one of the fortunate ones. Her older brother Robert had gone on ahead to South Africa and had written an affidavit that he would support her until she was able to earn her own keep. Even this was not so easy: After years of encouraging European immigration, the South African government—prompted by Afrikaner ministers, many of whom had studied in Germany and embraced the ideology of National Socialism—passed an “immigration quota bill” with the specific goal of limiting European Jewish immigration. Robert had only been able to get his visa by subterfuge. He learned that you had to prove to South African immigration officials in London that you had plenty of money, so he borrowed 50 pounds from a friend, showed the money when applying for his papers, and then promptly returned it to his pal who was waiting outside the embassy.

Almost five years later, in 1941, she married my father, a Scottish Jew, who later became the editor in chief of a black South African newspaper, The Golden City Post, and (on an interim basis) of its sister publication, Drum Magazine, journals staffed by a vibrant group of black African writers and photographers whose influence has led to that period being known for “The Drum Generation.” His work and his friendship with Nelson Mandela and other anti-Apartheid figures led to increasing scrutiny and pressure from the police and Apartheid officials. In the late 1960s, 30 years after she first fled her homeland, my mother found herself again in a position of being forced out of the country where she lived. This time, she would move to England, a relatively easy move bureaucratically as my father had been born in the U.K. and there was no trouble getting visas. It was not such an easy move for my brother and myself, young teens (I was 12) who found ourselves wrenched out of a South African summer into a British winter and into the damp, unfriendly corridors of an all-boys English school.

As a teen, I was surprised by my mother’s intense dislike and disdain for England. When the national anthem played at the cinema or theater, she would quietly mutter “God save your bloody queen.” I chalked it up to her hatred of the cold, damp weather—such a contrast with the brightness and warmth of South Africa—and the exchange of a lively if dangerous political engagement for the dull safety of London.

It was only years later, when I came across my mother’s own teenage diaries, that I understood the depth of dislike she held for Britain, stemming from long before she moved there. Hidden between fair copies of famous German poems in what appeared to be merely a school notebook was an account of her longing for the apparent safety of England. She wrote of her life in Germany: “Sometimes I despair when I see the atmosphere I am forced to live in.” Hence her shock at her treatment as a teenage girl trying to visit her aunt, a blow that carried over to the rest of her life.

She often told me the story of her visit to Aunt Daisy, the customs officer’s hostility, and her own humorous enjoyment of her acerbic response to him. I’d taken her casual telling as another example of her wit and refusal to be made to feel angry or let down. Until I read the diaries much later, I little realized at what cost this levity had come. It made sense that she never felt comfortable in England and remained skeptical of the British character. For somewhere inside of her was still the 15-year-old girl whose hopes were dashed by the callousness of an official threatening her with deportation.

I think of my mother when I see the reports of Syrian refugees detained at our airports and the continued efforts by the Trump administration to impose a blanket ban on refugees from certain countries. How furious this would have made her. I have read the articles and blog posts rejecting the comparison between today’s refugees and the Jews of the 1930s and ’40s and understand the argument against trivializing the Holocaust in any way through unnecessary comparison. But who better knows the pain and horror of being a rejected refugee than the loved ones of those who suffered a similar fate? Growing up, mine was a household where “Never Again!” did not just refer to our own tribe, but to anyone anywhere in the world under threat because of their race or nationality. We should none of us accept any less.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Tony Eprile is the author of the Koret Jewish Book Award-winning novelThe Persistence of Memory.