Religious Liberty Behind Bars

Two court cases involving Rastafarian inmates attract the attention of legal advocates of other faiths

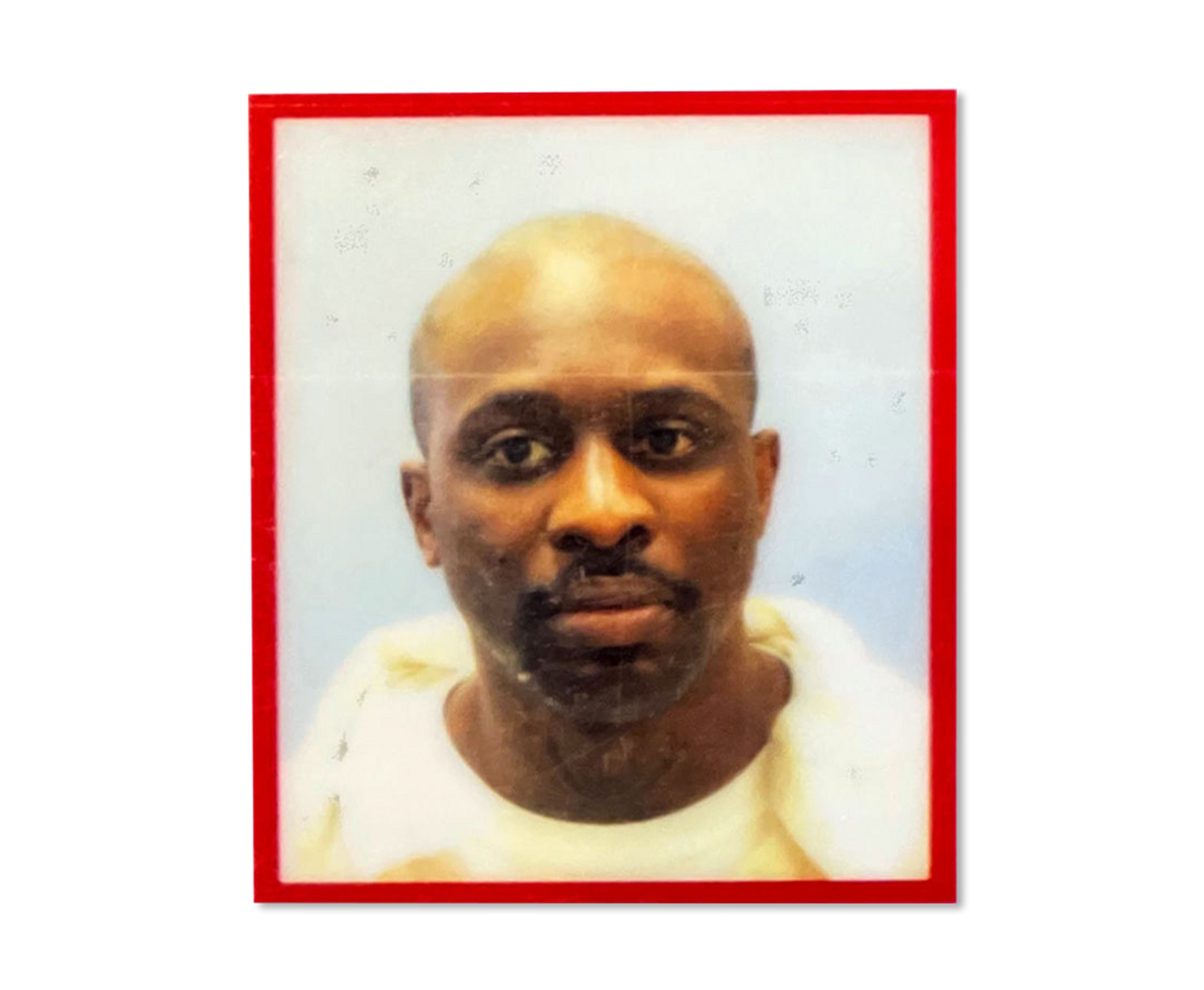

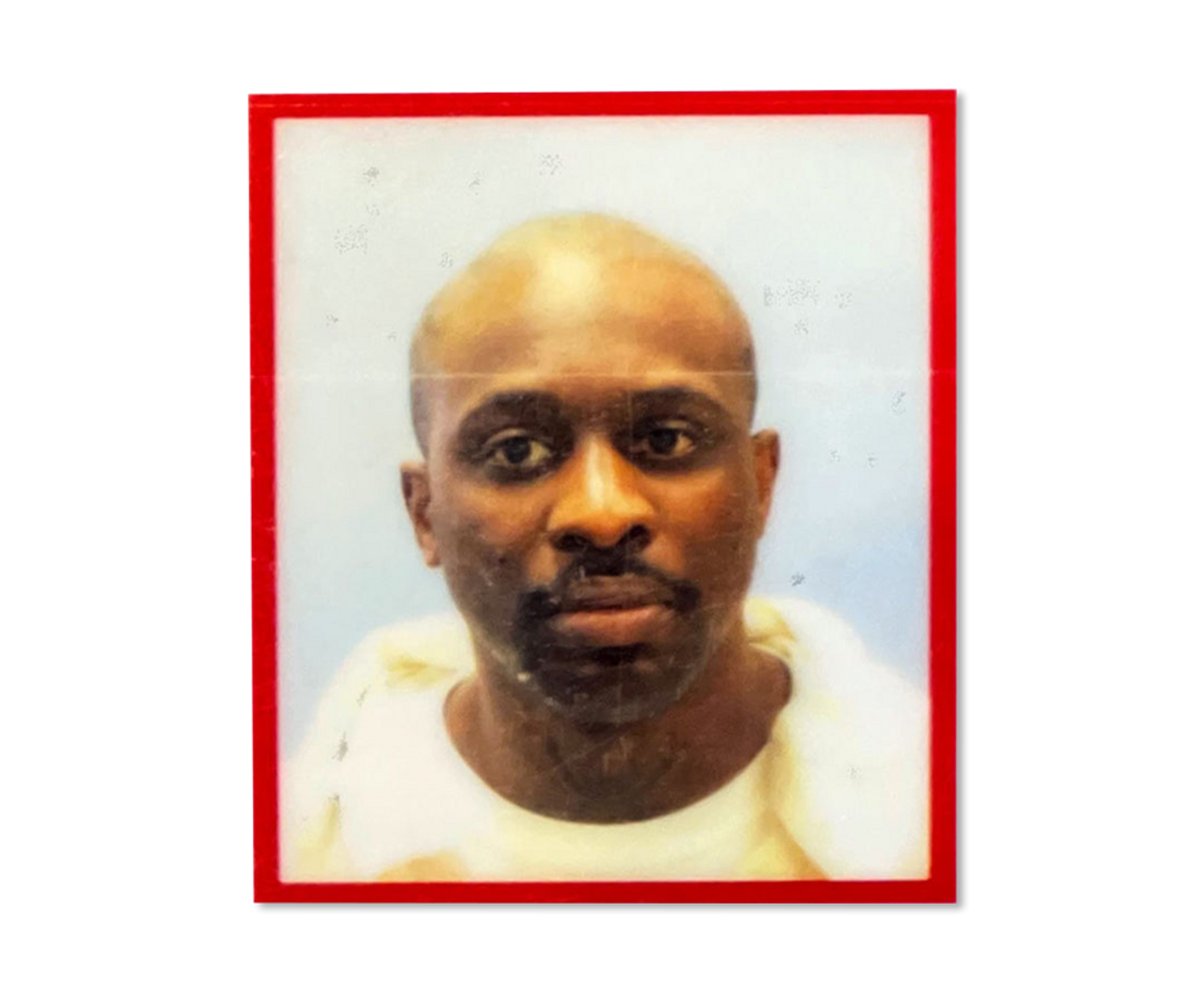

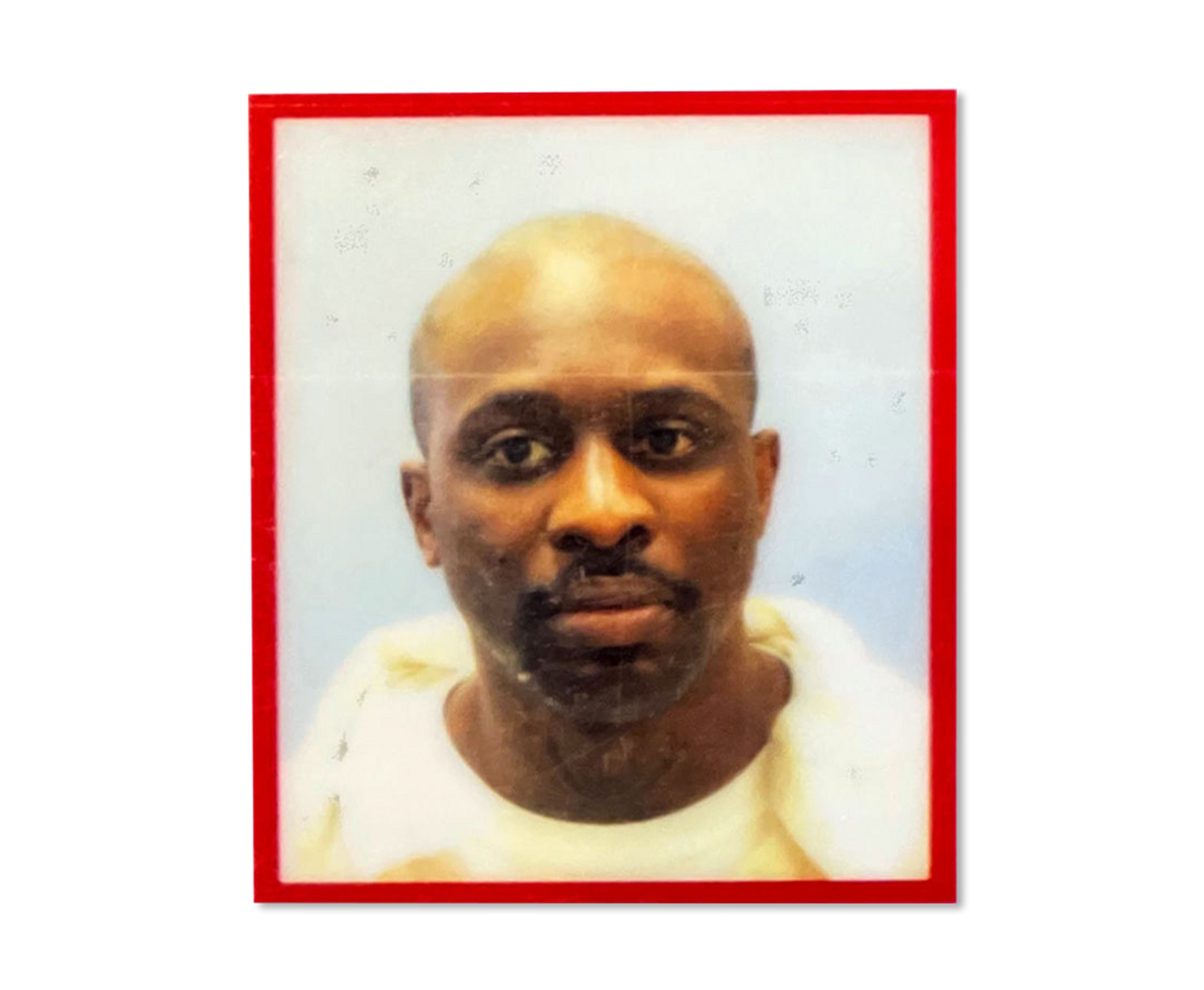

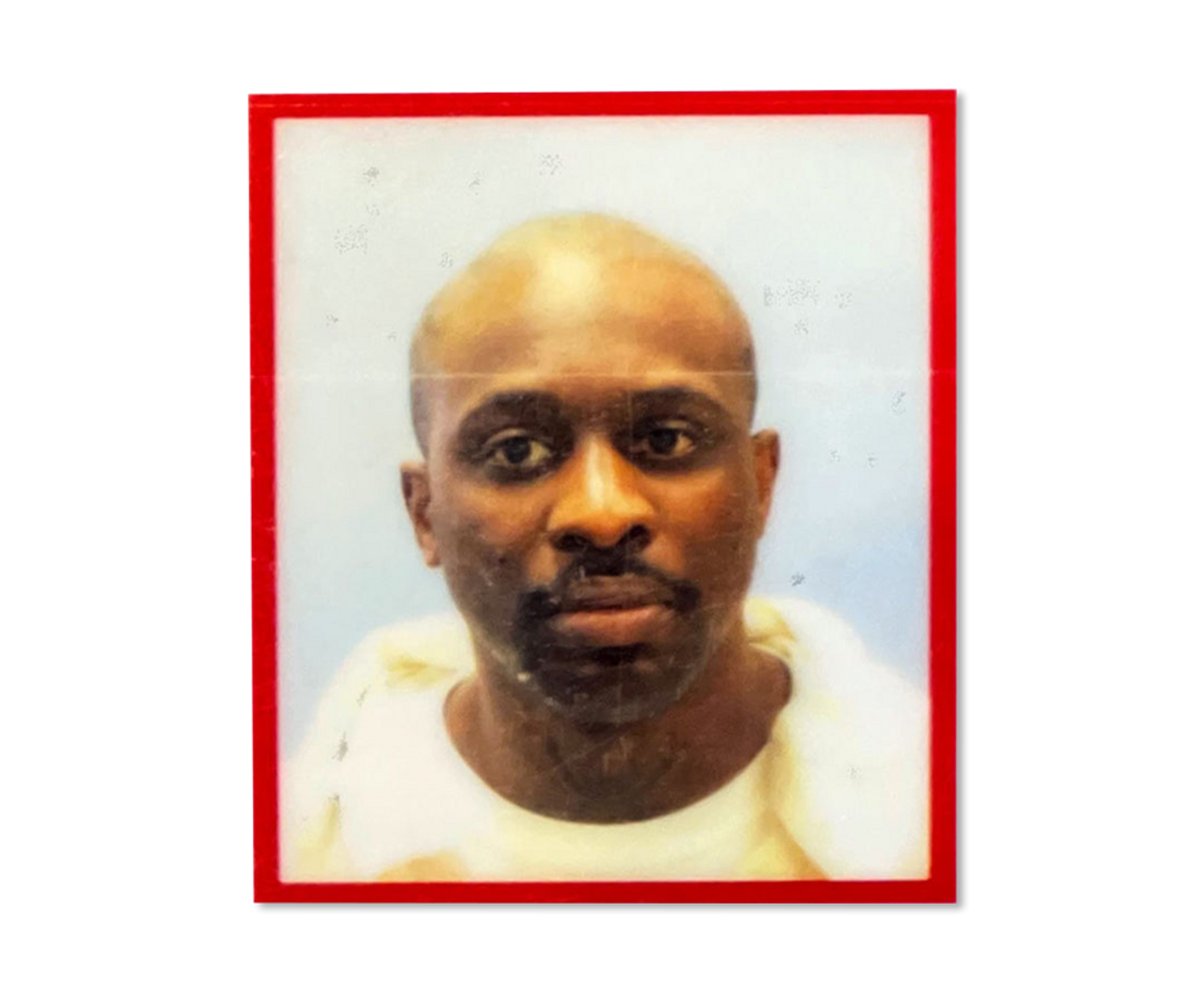

Last year, two separate cases were filed with the Fifth and Seventh Circuit Courts of Appeals, respectively, by Rastafarians seeking damages. Both litigants, Thomas Walker and Damon Landor, said that their dreadlocks were forcibly shaven while they were inmates, violating their religious liberty. At the center of both cases, which have attracted the attention of other religious groups who have filed amicus briefs in support of both Walker and Landor, are different interpretations of the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA). The 2000 legislation says that prisoners may “obtain appropriate relief” for violations of their religious liberty. But just what constitutes appropriate relief—or Rastafarianism, for that matter—is still up for debate.

According to the Notre Dame Religious Liberty Clinic, which filed an amicus brief for Walker in the Seventh Circuit, together with groups representing Anabaptists, Muslims, and Sikhs:

Walker began growing dreadlocks in 2013 after taking the Nazarite vow of separation, thus committing himself to never drink alcohol, never eat meat or dairy, and never cut his hair. In 2018 he was incarcerated at Stateville Northern Reception Center, where he was permitted to keep his dreadlocks. In early April 2018 he was transferred to Dixon and registered in the prison system’s online database as a practicing Rastafarian. He kept his dreadlocks for the first six weeks with no incident.

On May 25, 2018, a corrections officer informed Walker that his dreadlocks had to be removed for ‘security’ reasons. Despite telling the officer that cutting his hair would violate his religious beliefs by ‘sever[ing] [his] physical connection to Jah [(God)],’ Walker ultimately had to relent and allow the prison barber to sever his dreadlocks or else face severe disciplinary action and the forcible removal of his dreadlocks.

Landor’s lawyer, Zack Tripp, described his client’s case in an email to Tablet:

“In 2017, the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit directed Louisiana that it must grant religious exceptions and allow Rastafarian men like Mr. Landor to keep their dreadlocks in prison. Yet, when Mr. Landor handed that decision to the prison officials just weeks prior to his release, they tossed the court’s opinion, shackled him to a table, and had him shaven completely bald. What Mr. Landor’s allegations shows is that, without a damages remedy, Congress’s protections and the court’s decisions interpreting those protections aren’t worth the paper they’re printed on. No damages means no accountability.”

In neither initial case did courts in either state interpret the phrase “appropriate relief” to include financial damages, but rather injunctive relief—which would suspend the cutting of Rastafarian inmates’ hair—which was not applicable in either case, as the men had been released from prison. In Illinois, Walker’s case was thrown out after he was released from prison in 2021, while his original complaint, filed in 2019, was still in litigation. The Louisiana judge in Landor’s case dismissed it, writing in her opinion that Landor’s claims similarly became moot upon his release from confinement in 2021, and that RLUIPA’s appropriate relief provisions do not include financial compensation. (Josh Halpern, one of Tripp’s associates, will argue Landor’s case before the federal appeals court in New Orleans in May.)

Backers of the Walker and Landor cases believe that the ability to award damages ex post facto—providing financial compensation to the men after their release—will serve as a deterrent to future abuses of inmates’ religious freedom. There could be broader implications for both majority and minority religious groups if the interpretation of RLUIPA is expanded to include damages, since it also protects religious land use. An ability to sue for damages could serve as a protection against case obstruction and anti-religious animus in zoning processes for churches, mosques, and synagogues.

“It is hard to imagine an even moderately well-read person or even a person with just ordinary life experiences not knowing about Rastafarianism,” wrote Judge Iain Johnston, referring to the defendants in his opinion terminating Walker’s case. “Have they never listened to the radio? Have they never seen Cool Runnings? Did they not understand the Bob Marley reference in Caddyshack? Did these people really live such isolated and sheltered existences?” In a footnote, Johnston also gives due credit to Lee “Scratch” Perry and Toots and the Maytals (“legends in their own rights”).

If Johnston’s assertion that familiarity with portrayals in film and music are adequate to familiarize Americans with the minority faith of Rastafarianism, further reading on the historical and cultural context of the faith would suggest otherwise. In a 2002 Journal of Law and Religion article, “Chant Down Babylon,” authors Derek O’Brien and Vaughan Carter provide a brief survey of Rastafarianism’s development in Jamaica, where it began as a rejection of colonialism and its accompanying social, cultural, and legal structures.

Influenced by early 20th-century activist Marcus Garvey, Rastafarianism became associated with Pan-Africanism and Black pride sentiment, with “Babylon” serving as shorthand for the society and systems that exist outside of Africa. Garvey was influenced by Pan-African thought, the idea that people of African descent should unite around shared interests.

A nonhierarchical, nonproselytizing faith with no clergy or official doctrine, it is, according to O’Brien and Carter, “a wholly private affair.” Indeed, even to refer to it as Rastafarianism is, they write, an inaccuracy, since its followers (called Rastafari) “do not recognize any form of ‘ism.’” What we think of when we speak of Rastafarianism developed in the 1930s, coalescing around existing Afro-Christian syncretism in Jamaica, and Garvey’s vision of the establishment of a Black nation in Africa. In the Rastafarian conception, Ethiopia in particular emerged as Zion, the focus of their repatriation aims, in opposition to Babylon. According to O’Brien and Carter, a literal interpretation of an exhortation from Garvey, who was mistrustful of traditional Christianity, to put on “the spectacles of Ethiopia” to envision God, led to the deification of Ethiopian Emperor Haile Sellassie.

The practice of wearing dreadlocks emerged, they write, as a rejection of colonial conceptions of what constituted “beauty and good grooming,” and a mark of pride in African hair. It was also a function of Garvey’s conviction that Blacks should reinterpret the Christian Bible for themselves through a Pan-African lens. Such a reading would break open the scriptures in a new way, he believed, becoming a source of liberation. Colonial powers could no longer use the Old or New Testament to “domesticate,” in Garvey’s language. Hence, an interpretation of the Book of Numbers 6:5 to support the wearing of dreadlocks:

All the days of the vow of his separation there shall no razor come upon his head: until the days be fulfilled, in the which he separateth himself unto the LORD, he shall be holy, and shall let the locks of the hair of his head grow.

While the corrections officer defendants in Walker’s case may be excused for an unfamiliarity with Numbers, Marcus Garvey, and 1930s Jamaica, his lawyer thinks that ignorance is immaterial.

“Religious illiteracy isn’t a defense,” Tripp said in his email to Tablet. “Mr. Walker told the defendants at least four times [italics Tripp’s] over the course of multiple days that his dreadlocks were an expression of faith. At that point they were obligated at a minimum to consider accommodation. Instead, they forcibly shaved him bald.”

And Rastafarians have faced this challenge before: “The claimed ignorance of Rastafarianism is particularly incredible,” Johnston wrote in his opinion, “when claimed by individuals in the corrections field.” Court decisions about dreadlocks relating to the religious liberty of inmates date back at least to the 1980s and early ’90s, O’Brien and Carter write.

In a 2020 decision, Tanzin v. Tanvir, the Supreme Court decided that the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), an earlier law protecting religious freedoms with regard to the federal government, provided for retroactive money damages against federal officers who commit similar infractions to the ones alleged by Landor and Walker. What Tripp (who also represents Walker), and the groups filing amicus briefs, would like the circuit courts to decide once and for all is that RLUIPA, which is often described as RFRA’s “sister law” that applies to state governments, also allows for the same types of monetary damages after the fact.

“A damages remedy is critical because, in cases like these, RLUIPA is essentially unenforceable without one,” Tripp said in his email. “Without damages, prison officials could toss aside a binding decision from the U.S. Court for the Fifth Circuit and shave Mr. Landor bald, with impunity. Damages are the only way to deter the wrongdoers and to remedy the violations. Forward-looking relief does nothing to remedy the past harm. It is damages or nothing.”

The amicus brief filed by the Notre Dame Religious Liberty Clinic makes a similar point: “When religious minorities are not able to bring claims for damages, prison officials often lack incentives to sufficiently protect these religious rights,” their summary of argument reads. Additionally, under the current interpretation of RLUIPA, in which relief frequently takes the form of a court injunction against the course of action that infringes on an inmate’s religious liberty, as a result, “RLUIPA cases are often mooted before a plaintiff is able to receive relief” when prisoners are transferred or released.

Today’s religious majorities could be tomorrow’s misunderstood minorities in a secularizing country.

Even then, in the case of Landor, he alleges he presented a copy of a 2017 injunction against prohibiting dreadlocks in Louisiana prisons to the prison guards when he was transferred to Louisiana’s Raymond Laborde Correctional Center. Nevertheless, officers there shaved his head bald. About three weeks later, on Jan. 20, 2021, he was released. In the opinion dismissing his case, the judge notes that he has since started to regrow his locks.

Are prisoners entitled to ex post facto damages after they’ve left prison? In Walker’s case, although Judge Johnston in his summary judgment opinion criticizes the correctional officers’ claims of unfamiliarity with Rastafarianism, he also seems to suggest a “no harm, no foul” principle applies. He notes that before he was even released, Walker had begun to regrow his dreadlocks.

Informal estimates place the Rastafarian population at about 1 million worldwide. According to the 2020 U.S. State Department Report on International Religious Freedom data, they constitute only around 1% of the population within Jamaica itself. A project by CUNY professor Jennifer Lutin and her students on immigration and New York City attributes the spread of Rastafarianism to outward migration from the Caribbean that occurred in the 1960s and ’70s, and to the increased popularity of reggae. Their work asserts that the first mention of Rastafarianism in U.S. media appeared in 1971. From then on, Rastafarians did not receive much in the way of favorable coverage (the section on Rastafari on the website for Lutin’s class, “Peopling New York City,” cites references to “Rasta cultists,” and NYPD reports saying that Rastafarians “shoot whoever they feel like,” and use their religion “as a cover for their criminal activity”). Formal organized Rastafarian worship is less common than regular gatherings (called “reasonings”) to discuss scripture, conduct religious and spiritual education, and engage in ritual consumption of marijuana, usually at places like restaurants, dance and music clubs, and shops oriented toward Rastafarian clientele. These and other types of small-scale commercial activities, including selling marijuana, are the product of a common strain in Rastafarian thought that it is imperative to operate parallel enterprises within their own community to avoid participating in the economic system of Babylon. To the extent that organized Rastafarian worship exists, it is loosely regulated by orders or “mansions,” which have varying requirements and shades of belief among them. Mansions tend to be the loci of formal congregational worship for those members who engage in it. Lutin, et al. write that while the majority of Rastafarians in the U.S. flocked to urban centers on the East Coast, New York City emerged as the one capable of sustaining various Rastafarian mansions, in neighborhoods like Flatbush and Crown Heights.

Although judicial precedent establishes Rastafarianism as a legitimate religion from a legal viewpoint, its lack of formal membership requirements or initiation rites can make it difficult to distinguish, O’Brien and Carter write, “between the real Rastafarian and the charlatan. ”Furthermore, in establishing the sincerity of religious beliefs (something the 1944 Supreme Court decision United States v. Ballard determined that the court could scrutinize), they state that Rastafarianism’s blend of religious practice with cultural and political movements mean that a Rastafarian “may be sincere, but not sincerely religious.”

O’Brien and Carter hold up Rastafarian religious liberty controversies as a distillation of the tension inherent in the U.S., between majoritarianism and pluralism. On the one end of the ideological spectrum, there is the majoritarian view, articulated by the late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, that the legal privilege accorded to norms that suit majority religions in the U.S. “is an ‘unavoidable consequence of democratic government.’” On the other end of the spectrum is the pluralist view, that America is a more dynamic country for the diverse range of viewpoints and beliefs espoused by its citizens. However, the authors believe, even the more liberal conception of religious liberty upheld by the pluralists still tends to favor groups like the Amish and Native Americans, who are viewed as being within the American tradition and national conception of itself, over less familiar outsider groups, like Rastafarians, who can face what they refer to as “catechismal inquisition[s]” in court over the precise nature of their beliefs.

Much like Johnston’s critique of the corrections officers’ lack of familiarity with Rastafarianism in Walker, O’Brien and Carter give examples of Rastafaris themselves being submitted to criticism by courts for being ignorant of the history, key figures, and beliefs of their own movement.

But religious literacy cuts both ways.

Johnston’s critique that the correctional officers haven’t had the breadth of cultural experience to have seen the Jamaican bobsled movie or gotten all the references in a 1980 golf comedy, while noting that Walker was ultimately allowed to grow his dreadlocks back, seems to betray an attitude toward Rastafarianism that is not much more informed than the officers’. In an email statement through his lawyer, Walker said the officers who shaved his head “pointlessly violated my religious convictions.” As a Rastafarian, he said he wears dreadlocks “as a connection to God.”

The extent of many Americans’ religious literacy comes either from movies, books, and music, or from court cases, when a religion’s most controversial or least intelligible aspects are put up for public debate. In contextualizing the relevance of Rastafarians’ religious liberty challenges, O’Brien and Carter paraphrase authors Davina Cooper and Didi Harmon, writing that “with judicial efforts to define what it means to be a Jew, the problem is that the law is not merely reflective, rather it discursively produces its own version of Jews and Judaism.” Likewise with Rastafarianism, O’Brien and Carter write, since the most salient legal issues tend to relate to dreadlocks and marijuana use. Accordingly, they maintain Rastafarianism is easily reduced to caricature and, therefore, rendered more likely to be dismissed in court as an unintelligible subculture with little relevance to the broader American polity.

The understanding of religious liberty in American legal precedent is fairly broad, with standards of evaluation for a sincere belief, and markers like external practices, which parallel or are roughly analogous to traditional understandings of God and faith. However, amid widespread disaffiliation from traditional religion, traditional organized religions could become less familiar to the general public. An increase in religious liberty cases dealing with the sincerity of the faith held seems plausible. Can Scalia’s legal majoritarian argument with regard to religious minorities stand as more and more “conventional” faiths become religious minorities? What of those who may identify culturally with the religion of their family or country of origin, without being especially devout?

“When one comes to trial which turns on any aspect of religious belief or representation,” Justice Jackson wrote in his dissent in United States v. Ballard, “Unbelievers among his judges are likely not to understand, and are almost certain not to believe, him.” That was in 1944, when church attendance was much higher.

When Scalia, a Catholic, penned his decision on the majoritarian nature of religious liberty in 1990, his religion constituted nearly a quarter of the U.S. population. In 2022, Catholics had dropped from 25% of the U.S. population to 22%. Were his co-religionists today to face the same sincerity tests as the Rastafarians, grilled on their familiarity with the beliefs and practices of their faith, few would likely fare better: Church attendance is on a steady decline, and in 2019, barely one-third told a Pew research poll that they believed in a central tenet of the Catholic faith, the transubstantiation of the bread and wine at Communion into the literal body and blood of Christ. Nor is this prospect a far-off hypothetical. In January of this year, a Catholic Charities Bureau in Wisconsin asked the Wisconsin Supreme Court to consider a case in which their state has called into question their own doctrine. A state appellate court denied them a religious exemption, which would have allowed the Catholic Charities to opt out of the state-run unemployment program in favor of one they provide themselves, on the grounds that their activities serving the poor and disabled are not “inherently” religious.

Today’s religious majorities could be tomorrow’s misunderstood minorities in a secularizing country. The challenges that Rastafarians like Landor and Walker have received in court over their little-known religious faith has attracted the attention of the Anabaptist Bruderhof association, Muslim Advocates, the Sikh Coalition, Quakers, Reform and Orthodox Jews, Catholics, mainline Protestants, and Unitarians, all groups that have filed amicus briefs in one or both cases seeking damages.

“I am deeply grateful that so many different faith groups are supporting me and my cause,” Walker said in his email statement. “I’m hopeful that I will be able to win my case and help prevent Dixon and other prisons from mistreating others as they mistreated me.”

Landor echoes Walker in his own email statement, also sent via email through Tripp: “I brought this case to hold them accountable and to help ensure this doesn’t happen to anyone else—not in Louisiana or anywhere,” he said. “The support I’ve received from so many other religious groups and institutions gives me hope that things can change.”

This story is part of a series Tablet is publishing to promote religious literacy across different religious communities, supported by a grant from the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations.

Maggie Phillips is a freelance writer and former Tablet Journalism Fellow.