Return to the Valley of the Dolls

A snazzy reissue celebrates the 50th anniversary of Jacqueline Susann’s classic potboiler

This past July 4 did not mark merely our troubled country’s birthday. It also marked the 50th anniversary of the publication of the hot-pink-edged Valley of the Dolls. Jacqueline Susann’s first novel, a shocking tale of fame, friendship, fucking, and pharmaceuticals, was the fastest-selling novel in history: It sold over 31 million copies in 30 languages. The book’s 1966 publication was followed by two more juicy novels, The Love Machine and Once Is Not Enough; in 1973, Susann became the first novelist to have three consecutive #1 New York Times best-sellers. After The Love Machine booted Portnoy’s Complaint from the top spot, Susann said of Philip Roth, “He’s a fine writer, but I wouldn’t want to shake hands with him.”

Critics mocked her work relentlessly. In a New York Times review, Gloria Steinem sniffed that Valley of the Dolls was “for the reader who has put away comic books but isn’t yet ready for editorials in The Daily News.” Nora Ephron damned it with faint praise, saying it was “like reading a very, very long, absolutely delicious gossip column full of nothing but blind items.” A New York Times review of the classically camp 1967 movie sneered, “Bad as Jacqueline Susann’s “Valley of the Dolls” is as a book, the movie Mark Robson has made from it is that bad or worse. It’s an unbelievably hackneyed and mawkish mish-mash of backstage plots and “Peyton Place” adumbrations in which five women are involved with their assorted egotistical aspirations, love affairs, and Seconal pills … all a fairly respectful admirer of movies can do is laugh at it and turn away.” And on the David Frost Show, pinched homunculus John Simon queried Susann, “Do you think you are writing art, or are you writing trash to make a lot of money?” Susann answered, “Little man, I am telling a story. Now, does that make you happy?” (On the show, Simon also told Susann, “I would rather see dogs fornicate than read your love story.” An audience member shouted, “I would rather see dogs fornicate than listen to you talk!”)

Reading Valley of the Dollstoday can be a jarring experience. In some ways it feels absolutely up to the minute: the depiction of beautiful women who seem invincible but have little power in a world run by men; the brutality of getting older in the public eye (“for celebrities—women stars in particular — age became a hatchet that vandalized a work of art”); the pressures that drive women to indulge in “dolls,” Susann’s word for pills. (Her publisher begged her to change the name, fearing the book would be shelved in the children’s section. She refused.) There are lots of great one-liners: The main character, Anne Welles, observes of Hollywood, “A wife held the same social status as a screenwriter—necessary but anonymous.” Uneducated young vaudevillian Neely O’Hara ponders her friend Jennifer’s success in art films: “Maybe they didn’t think anything of it in Paris, but subtitles under a bare ass still didn’t make it art.” A producer signing Jennifer to a big American movie deal sighs, “Just my luck—the French get her when she’s naked … I have to get her when she’s an actress.” But the book can also feel terribly dated, what with its incessant homophobia (so much disgusted talk of fags, faggots, queers, and Lesbians—with a capital L, please!) and sizeism (you can feel Susann’s visceral horror of fat: “the explosion of her cheeks,” “the mammoth mass of flesh,” and lines like “she’s as fat as a pi g— but she can sing!”) The book is oddly prudish; Susann writes far more vividly about being swept away by barbiturates than by passion. And I learned a truly vile bit of slang for a woman who’s just had sex with one man and is willing to have sex with another: a wet deck.

***

Susann’s life wasn’t easy. The Jewish Women’s Archive tells of her childhood in Philadelphia, where she was born to a philandering artist father and teacher mother. When she was 7, her maternal grandmother, Yuccha Kahalofsky Jans, gave her a diary. (There’s a photo of Kahalofsky holding her own childhood diary, in which she recorded the story of her family’s escape from pogroms in Kiev.) The name Susann comes from Shushan, the capital of Persia in the Purim story.

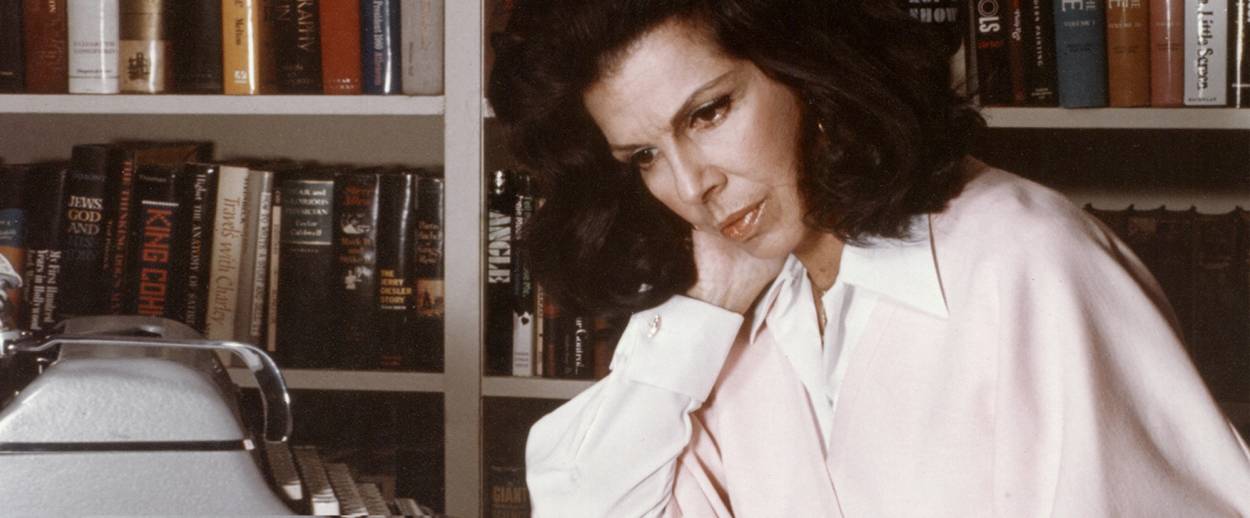

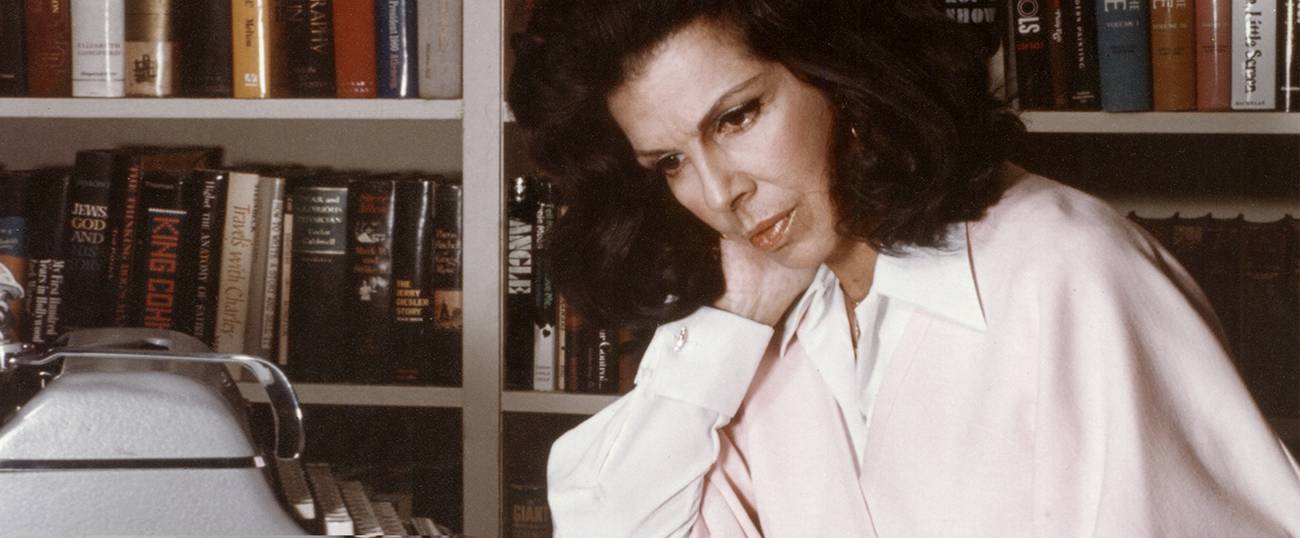

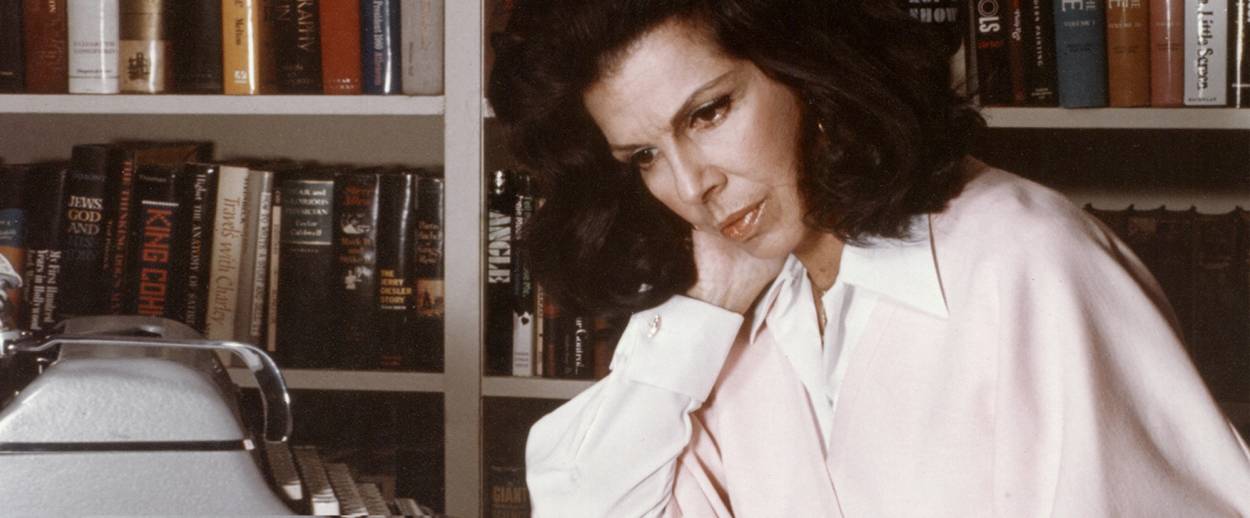

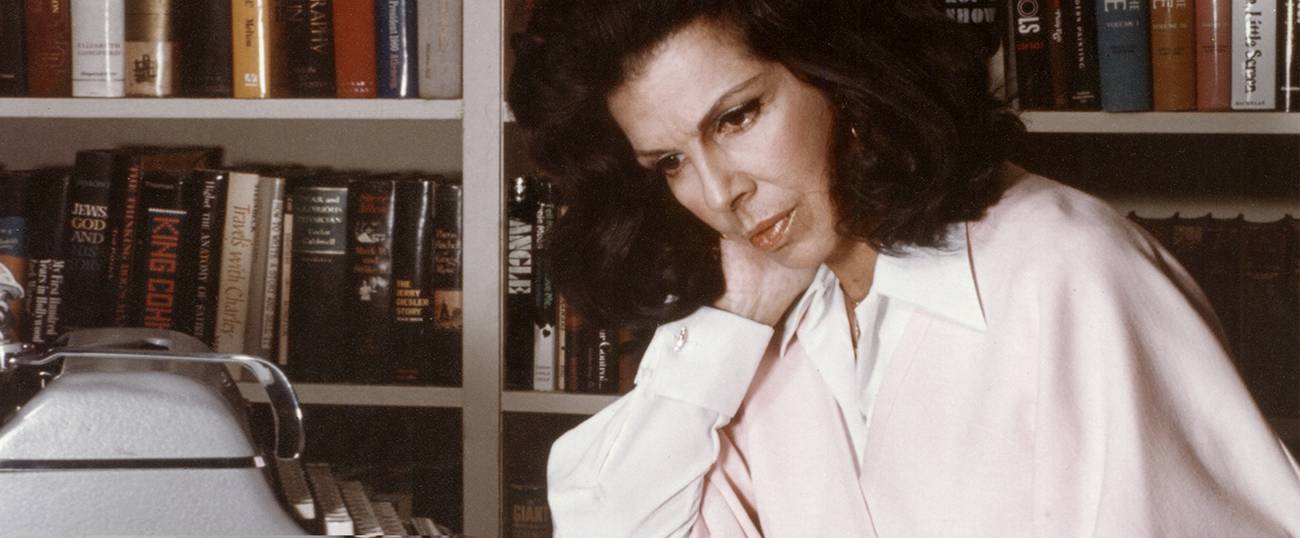

Susann grew up to be a frequently fired actress, then a failed playwright. At the age of 44, she was diagnosed with breast cancer. (“I can’t die without leaving something—something big,” she told her diary. “Let me live to make it.”) Her husband, Irving Mansfield (ne Mandelbaum), a theater producer and publicist, was then out of work. Their child, Guy, who had repeatedly smashed his head against the walls of his crib and flown into rages and never spoke, was diagnosed with autism. Guy was given electroshock treatments and other therapies, but nothing helped. His parents had him institutionalized.

In 1963, Susann was contemplating suicide by pills. But sitting under a tree in Central Park with her poodle, Josephine, she suddenly felt the presence of God. God told her she would live 10 more years and become the most popular author in the world. She immediately sold a collection of comic essays about Josephine, which did respectably. She marketed herself as a TV personage, doing interviews with the poodle while the two wore matching jackets.

Then she sold her Valley of the Dollsmanuscript—the original is now up for auction, expected to fetch $25,000 to $50,000—to a swinging publisher named Bernard Geis, who a couple of years earlier had published a sexy book by a certain then-unknown advertising copywriter named Helen Gurley Brown. Geis knew how to sell sizzle.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin, who later co-founded Ms. magazine, was Geis’ director of advertising, publicity, and promotion. She sent out 1,500 review copies of Susann’s book, along with a note on a prescription pad saying “Take Valley of the Dolls in heavy doses for the truth about the glamour set on the pill kick.”

Mansfield and Susann revolutionized book publicity. They created the modern-day book tour. They figured out how to use television to sell books effectively. They did market testing. They reportedly found out which bookstores’ sales figures made up the New York Times best-seller list’s tallies so they could focus their energies on those stores. Mansfield dispatched friends who were traveling to a city with one of those stores in it to go and buy up every copy of his wife’s books. Susann kept a file with facts about individual booksellers in it, so she could charm them by seeming to remember them. “A new book is like a new brand of detergent,” she once said. “You have to let the public know about it. What’s wrong with that?”

She became one of the wealthiest self-made women in America. Her writing study, decorated for her by Mansfield in their palatial 24th-floor condo on Central Park South, had Pucci drapes and hot-pink patent leather walls. She knew everyone. She tried to get Henry Kissinger, when he was the secretary of State, to falsify her passport to make her younger. (He didn’t do it.)

Judith Rosenbaum, director of the Jewish Women’s Archive, told me in an email interview, “Though I’m not a huge fan of Valley of the Dolls, I admire Jackie Susann for her insistence on putting women and their friendships at the center of her stories, and for her insistence also on putting herself as author at the center of her work. She was ambitious, bold, and determined to succeed despite the obstacles in her way, and her success had a huge impact on the publishing industry and on the representation of women in popular culture.”

***

Part of the fun of Valley of the Dollsis figuring out which celebrity each character is supposedly based on. Neely O’Hara is clearly Judy Garland, the sassy yet fragile addict with an amazing voice who fights stage fright, addiction, and poundage. (A thousand gay men have shrieked the immortal line from the movie’s drugged-up, wild-looking Patty Duke: “I’M NEELY! NEEEEEEELY O’HAAAAAAARAAAAAA!”) The old, brassy, fat Broadway dame who has a memorable, wiggy dustup with Neely in a restaurant bathroom is obviously Ethel Merman. (There were rumors that Susann and Merman had once had an affair. When asked what Merman thought of Valley of the Dolls, Susann said, “We didn’t speak before the book came out. Let’s just say that now we’re not speaking louder.”) Sweet, doomed Jennifer with a body to die for seems a carbon copy of Marilyn Monroe.

Like Sex and the City, which followed in Susann’s footsteps decades later, Valley of the Dollsisn’t actually sexy. Susann is much more interested in writing about women—and the vicissitudes of female friendship—than about men. In real life, Susann had a close circle of girlfriends; they called themselves The Hockey Club. The name came from the Yiddish word hock, as in hock a tshaynik—“bang a teakettle.” The Yiddish idiom means to rattle on loudly and annoyingly, but Susann’s friends meant “bang” in a different idiomatic way—as in, to have sex with. “In addition to talking about their own romantic adventures, the women—many of them former actresses (Joyce Mathews, Joan Sitwell, Dorothy Strelsin) who had married well—spied on one another’s errant men,” Vanity Fair noted.

Men in Susann’s world and work were hugely problematic. Like Mr. Big in Sex and the City, Lyon Burke in Valley of the Dollsis the heroine’s grand passion and also a dominating, unavailable, unfaithful alpha-hole. The only truly menschy guy in the whole book is Henry Bellamy, the theatrical lawyer—clearly based on Mansfield—who gives Anne a secretarial job in New York City and forever looks out for her interests. When they meet, Bellamy self-deprecatingly calls himself a schmuck; WASP-y Anne has no idea what he’s talking about. “Excuse the language,” he tells her.

“What language? Schmuck?” She repeated it curiously. It sounded so outrageous coming from her that he laughed out loud. “It’s a Jewish word, and the literal translation would make you blush. But it’s become slang — for dope.”

He confides that he was born Birnbaum, but when he worked as the entertainment director for a cruise-ship company and wrote for its newsletters, “they didn’t like their fancy columns headed ‘Boating by Birnbaum,’ so one guy suggested Bellamy … but I never let anyone forget that under Bellamy there’s always Birnbaum.” Indeed, he’s the only character who’s consistently true to himself.

No one in Valley of the Dollswinds up happy. As Simon Doonan, who wrote the preface to the 50th-anniversary edition notes, “It’s Balzac bleak. It’s Dostoevsky greige.” (Perhaps you’ve seen the cute yet sinister pillboxes labeled “Dolls” made by Doonan’s husband, ceramicist Jonathan Adler.) The awareness of human frailty and faithlessness, and the drumbeat of time, cast a pall over everything. “If you allow yourself to think of the future—any personal future—you lose your nerve,” Lyon tells Anne. “And suddenly you recall all the senseless time-wasting things you’ve done … the wasted minutes you’ll never recover. And you realize that time is the most precious thing. Because time is life. It’s the only thing you can never get back … a second—this second—when it goes, it’s irrevocably gone.”

Susann was acutely aware of how little time she had. As she was writing her third novel, her cancer returned with a vengeance. She’d gotten the best-selling status God had promised her, along with the 10 years, plus a year and a half more. She died at 56, on Sept. 21, 1974. She lied about her age up until the end.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.