A Reunion Postponed

As refugees streamed out of Ukraine, an Israeli man offered shelter to the descendants of the people who once saved his ancestors from the Nazis. It wasn’t quite as simple as it seemed.

This was shaping up to be a poignant, poetic-justice, what-goes-around-comes-around story of two Ukrainian men who fled Russia’s bombardment of their hometown for shelter in Israel at the home of a Jewish man whose family their ancestors had rescued during the Holocaust. It would have covered the trio’s likely chats in the Israeli’s living room, their commiserating about war and demonizing and mass killings of civilians, their pondering survival and sacrifice and dedication.

The Ukrainian men’s forebears had saved the Israeli’s kin from 1941 until the Nazi occupation ended in 1944, and now the Israeli anticipated hosting them until Russia’s war in Ukraine ends. He’d already done so much for them. He’d urged them to leave the war zone, paid for their extended hotel lodging in Poland while they awaited a flight to Israel, and pledged to open his home to them. His daughter even installed new appliances—a mini-refrigerator and stove—in the bedroom where they’d be staying.

But then a grave, last-minute crisis postponed the reunion. It still hasn’t happened, despite the Ukrainians reaching Israel more than three weeks ago. Still, the principals adamantly affirm that they’ll see each other soon, that they’ll close the circle.

They just don’t know when.

In the early-morning darkness of April 8, the Ukrainians—Vladimir Kuklin, 68, and his son Sergey, 36—landed in Israel on LOT Polish Airlines flight 151 from Warsaw. They’d expected to stay with Boris Fradkin and decompress from the war’s trauma. Their world began collapsing at 6 a.m. on Feb. 24, when booming missile strikes woke Sergey in the bedroom of the house he and Vladimir share in Starokostiantyniv, a town of about 35,000 people in western Ukraine.

Sirens sounded plenty in the war’s first week to warn the town’s residents about Russian bombs, each wail sending the Kuklins racing to their basement. Not quite racing, really, since Vladimir needed to help move Sergey, who’s had cerebral palsy since birth and walks haltingly. Once, with the power out, Sergey fell going to the kitchen to fetch a flashlight. He hurt his back, making walking more difficult. Next siren, he feared, he might hit his head or fall down the stairs.

That’s when, prodded by Fradkin, the Kuklins decided to leave Ukraine—and so they did on March 8, riding a bus westward to Krakovets and from there crossing into Poland, where they stayed the first week with a friend.

Russia was targeting Starokostiantyniv because of its air force base, seven miles from the Kuklins’ home. The base is where Vladimir worked as an aircraft technician before retiring. His son-in-law Alexei, an air force captain, is now serving there. Vladimir’s daughter and grandson remain behind with Alexei, even as more than 5 million of their countrymen have fled Ukraine.

Russian bombs also hit an oil depot in the village of Straklov, about 100 miles to their northwest. On that property, beneath barrels arrayed as camouflage, the Jewish owner of the depot, Ben-Zion Binshtok, and his wife, Sara, hid in a pit for more than a month following the Nazis’ occupation in June 1941. A watchman there, Ivan Romaniuk, saw to his employers’ needs, all the while building a bunker under the pigpen next to the home he shared with his wife, Alexandra, and their daughters Tatiana and Olga.

That autumn, Ivan moved the Binshtoks to his bunker, where the Romaniuks cared for them. Ivan traded some of the depot’s benzene and kerosene for the extra food needed. The girls brought the Binshtoks their meals and emptied their pails of body waste. The danger multiplied during the time a German officer lived with the Romaniuks and met there with fellow Nazi soldiers. Whenever they approached, Tatiana called out, ostensibly to the family’s dog, to warn the Binshtoks.

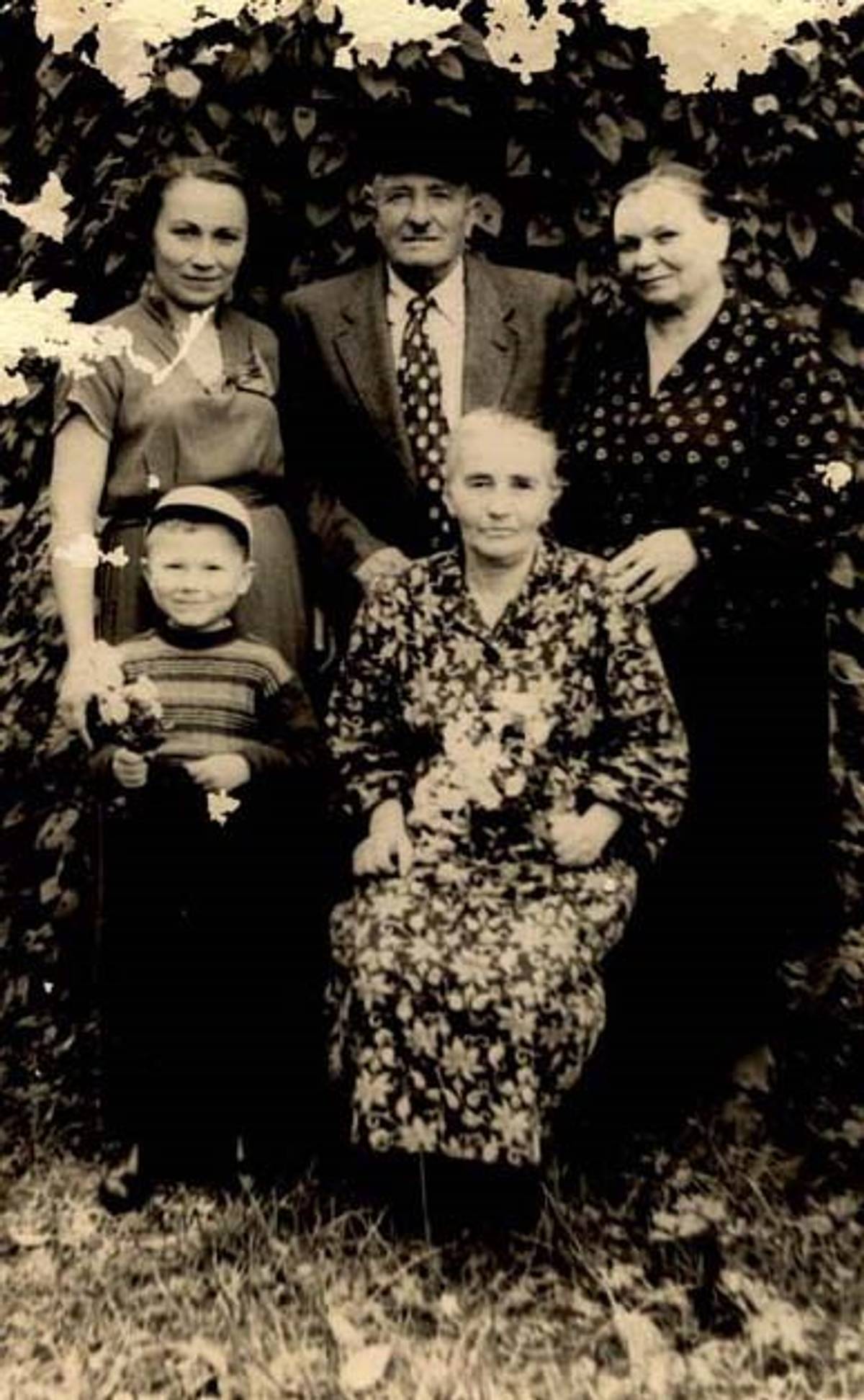

The Jewish couple survived there for two and a half years until being liberated after the Germans retreated, and later resettled in Saltykovka, near Moscow. Ivan had been killed while serving in the Soviet military. The other three Romaniuks and, later, the daughters’ families would sometimes travel to Russia to visit the Binshtoks in the 1950s and ’60s.

Those gatherings included Vladimir Kuklin, Tatiana’s son; and Boris Fradkin, the Binshtoks’ great-nephew—the grandson of Ben-Zion’s murdered brother, Yisrael Dov. The Binshtoks’ children were murdered during the war: one by the Nazis and the other by fellow partisans.

“I remember the warmth with which they honored them,” Fradkin recalled of the Binshtoks’ hosting of the Romaniuks, “and the love with which [the Romaniuks] spoke with the Binshtoks. They were good people, with each taking care of the other during the war and after the war, people who remembered the good done to them and didn’t hesitate to do good themselves.”

The young Fradkin witnessed his great-uncle Ben-Zion’s gratitude. He remembers the 20 or so fruit trees dotting his great-uncle’s yard and how every summer he and Ben-Zion walked for miles, pulling a wagon heaped with boxes of apples and other produce to the post office. That’s where Ben-Zion mailed the boxes to Alexandra, Vladimir’s grandmother. Every few years, Ben-Zion would sell another of his family’s homes—they retained three or four from before the war, although the Soviets seized the depot—near Starokostiantyniv and send the proceeds to the widow.

The lesson stuck. Like Ben-Zion, Fradkin has assisted the Romaniuk clan.

Fradkin, a 74-year-old retired engineer, moved to Israel in 1977. When he was in Ukraine in the 1990s to see the Kuklins—he’s made about seven such visits—Fradkin bought a new computer for Sergey, a technology whiz as a child who repairs and builds computers for a living, although his degree is in law. Other times, he covered some of Sergey’s college tuition and gave Tatiana money for dental work, repairs to her house’s boiler, and cardiac and cataract medications.

“I just felt that they deserve it. My moral debt is to be concerned for them,” Fradkin explained. “The circle is being closed. They saved my grandfather’s brother and [his] wife, and now I’m saving them.”

Fradkin was speaking a few hours after the Kuklins landed at Ben-Gurion Airport and Vladimir wheeled a small red suitcase containing some clothes for him and his son off the plane. It also held important documents: the men’s college diplomas; a record of their coronavirus vaccinations, all occurring in Marchduring their month long stay in Poland; the travel documents that Israel issued, also in Poland; and the Ukrainian military’s documents exempting Sergey from service due to his disability.

They carried, too, the medallion and certificate awarding Ivan and Alexandra Romaniuk, Vladimir’s maternal grandparents, official designation as Righteous Among the Nations—non-Jews who rescued Jews during the Shoah, often at great peril and with no expectation of reward. Yad Vashem, Israel’s foremost Holocaust-commemoration institution, has bestowed the award on 27,921 people since 1963.

The minivan they entered outside the terminal took the Kuklins to a Jerusalem hotel, though, not to Fradkin’s home in Oranit, a small community near Petach Tikva.

The joyful reunion of gratitude I expected to witness still hasn’t transpired because, shortly before the Kuklins’ flight departed Poland, Fradkin entered Petach Tikva’s Beilinson Hospital with a circulatory problem.

“Come and speak with me instead in my hospital room,” Fradkin said before leaving home.

And so that Friday I went to the third floor, room 20, the front bed of three, and pulled my chair next to Fradkin’s mattress. He seemed fine. His legs and feet stuck out below his gown’s hem. He turned his smartphone to display a photo of his left ankle, the side out of sight. It appeared several ugly shades of purple.

“The doctors will run some tests and treatments, and hit me with antibiotics,” he said. “They’ll know within 30 days whether everything is OK. If it’s not, they’ll amputate my leg below the knee.”

That Sunday, I telephoned to check on Fradkin. He sounded groggy. The doctors’ timeline had changed drastically since we’d met.

“Yesterday,” he said, “they amputated my leg.”

Post-op complications and infections have kept Fradkin at Beilinson and delayed his transfer to a rehabilitation hospital, where a month or so of therapy awaits.

“It’s terrible,” he said by phone in late April, in somewhat of an understatement, of the turn of events. “I’d prepared everything to receive them. I wanted to host them.”

Their reunion still may happen, depending on when the war in Ukraine ends and whether the Kuklins can visit him in the hospital. Fradkin said he prefers to look at the bigger picture.

“I did get them out of Ukraine. The most important thing is they’re not in danger,” he said. “Life continues.”

Meanwhile, the Kuklins are hardly living it up as tourists, even though their hotel in downtown Jerusalem sits less than three miles from the Old City. For the first 15 days, they were stuck in their fourth-floor room that looks onto the back of an apartment building. Both men had tested positive for coronavirus—then tested positive again. They watched a lot of television and talked. Sergey continued learning English online.

Finally, their COVID-19 tests turned up negative, so they took a brief walk outside. The next day, I met them in their room for an extended conversation. In the hotel’s lobby, a uniformed soldier stood at a whiteboard sandwiched between couches, teaching other new arrivals the Hebrew basics: the alphabet, days of the week, and how to say, “What is your name?”

Across the hall, Ukrainian-language pamphlets lay on a kiosk shelf of the Ministry of Immigration and Absorption. A representative at the booth, Anastasia, noted that 120 Jewish arrivals and five descendants of Righteous Among the Nations honorees are staying at the hotel, one of several around the country secured for this purpose since Israel began welcoming the war’s refugees. Anastasia was there to direct them to off-site advisers on such services as employment, banking, health care, schools and housing. She’d been through something similar upon arriving from Ukraine 25 years ago.

As of April 28, 26,440 Ukrainians (8,047 of them Jews) have reached Israel since the war began. Twenty-three of the arrivals are, like Vladimir and Sergey, descendants of 12 people designated as Righteous Among the Nations.

“The fact that [the 23 refugees] sought shelter here, and saw the importance of coming here, shows their connection to the Jewish people,” said Tanya Manusova, a Yad Vashem official involved in the effort. “We see the importance of acting in an emergency for those whose ancestors saved Jews.”

The museum has played a key role in bringing rescuers’ descendants to shelter in the Jewish state, along with Israel’s Embassy in Warsaw, the Jewish Agency for Israel, and the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee. So have Israelis whose relatives the Ukrainians’ ancestors had rescued. Some other Righteous descendants even settled in Israel and now find themselves housing their relatives who recently fled Ukraine.

Seven of the 23 new arrivals wish to remain permanently in Israel, but that’s not a given that this will happen. Righteous honorees are eligible for citizenship—one 95-year-old woman is considering relocating to Israel—and their children and grandchildren may stay for up to five years and receive work permits. Great-grandchildren may come only as tourists and aren’t allowed to work in the country. Like all Ukrainian refugees, they likely will be allowed to remain until it’s safe to return home. Discussions are underway with at least one member of Knesset about amending the law to enable them to work if they wish.

Like most of the others, the Romaniuks’ grandson and great-grandson plan to go back to Ukraine when the war ends. They are in Israel on two-month visas that can be renewed.

“I want to return home to live—normally, without the bombing,” said Vladimir.

Said Sergey: “I really want to go home. It all depends on how events develop in Ukraine.”

Our conversation turned to Fradkin’s medical condition. The men can’t fathom the harsh news and unfortunate timing that took him away just as they arrived. They occasionally speak with him by phone. When Vladimir offered to visit the hospital to assist in his care once their coronavirus confinement ended, Fradkin assured him that the medical staff is attentive.

“Boris said he’s very happy we want to come, but he has two nurses,” Vladimir said.

“I feel like I will never be able to repay the debt to him. I am very worried about him now, about his health,” said Sergey, who calls him Uncle Boris or Uncle Borya.

“It always amazes me that the choice my great-grandparents made affects me now,” he said. “Imagine if they hadn’t done that, if they’d made another choice. I wouldn’t be sitting with you right now. When you save one life, you save the world. You see, this is how the circle is closed. I have never been a believer, and I did not believe in fate.”

By this time, we were all sitting on a bench on Jaffa Road. Vladimir stoically had pushed his son in the wheelchair provided free by a national organization that lends medical supplies. On the 10-minute walk, I’d twice asked whether I could lend a hand by pushing one of the wheelchair’s grips in the afternoon heat. Vladimir gently shook his head and continued pushing. I thought of the apocryphal Boys Town line, “He ain’t heavy; he’s my brother,” and how it applies to both sides of the Binshtok-Romaniuk/Fradkin-Kuklin equations.

Shoppers strode by, many entering and exiting Machne Yehuda, the capital’s main open-air market. The light rail trains whooshed by.

Out of the blue, Sergey turned to me and said, “Why is fate cruel to kind people?”

UPDATE: Boris Fradkin passed away on September 2, 2022, at age 74. The cause of death was a heart attack following a catastrophic decline in the preceding months: circulatory problems that necessitated the amputation of his left leg, then a cancerous lump discovered on his neck. While the Kuklins, once they reached Israel, spoke by phone many times with Fradkin, they never got to reunite, to hug each other. Their visit to the shiva house, said Sergey, was “one of the most difficult days in my life.”

Hillel Kuttler, a writer and editor, can be reached at [email protected].