Where Are All the Scary Jewish Children’s Books?

It’s Halloween. Kids want to be scared. And there is a gaping, bloody hole in the canon.

Hey, at least we have Eric A. Kimmel.

Fans of scary Jewish kidlit rightly celebrate the author of the scariest and best Jewish picture book of all time, Hershel and the Hanukkah Goblins. But Kimmel has written numerous shivery, spooky stories for kids: There’s the High Holidays story Gershon’s Monster, creepily illustrated by Jon J Muth, about a man who spends the year sweeping his demon-shaped sins into the basement, before stuffing them into a huge sack on Rosh Hashanah and tossing them into the sea. He finds out, to his horror, that you can’t get rid of misdeeds that way. Mwah-ha-ha-ha-ha, you’ll never look at tashlikh the same way. Kimmel also wrote Zigazak!, a fun-scary, not scary-scary Hanukkah story about two troublemaking Hanukkah devils with cartilaginous wings and forked tails, illustrated with pleasantly chilly darkness by Jon Goodell. And Hayyim’s Ghost, a folkloric-feeling story about an evil woman named Bayla Esther whose nonevil husband Hayyim dies … and guess what he comes back as. And The Mysterious Guests, in which two brothers—one rich and stingy, one poor but generous—learn a memorable holiday lesson from three unexpected visitors. It puts the sukkornatural in Sukkot. (Sorry.) Some of these books are out of print (a shonde), but what with Kimmel being a multiple National Jewish Book Award-winner and Sydney Taylor Lifetime Achievement Award-nabber, your library probably has copies. And there are plenty of used editions floating, specterlike, around the internet.

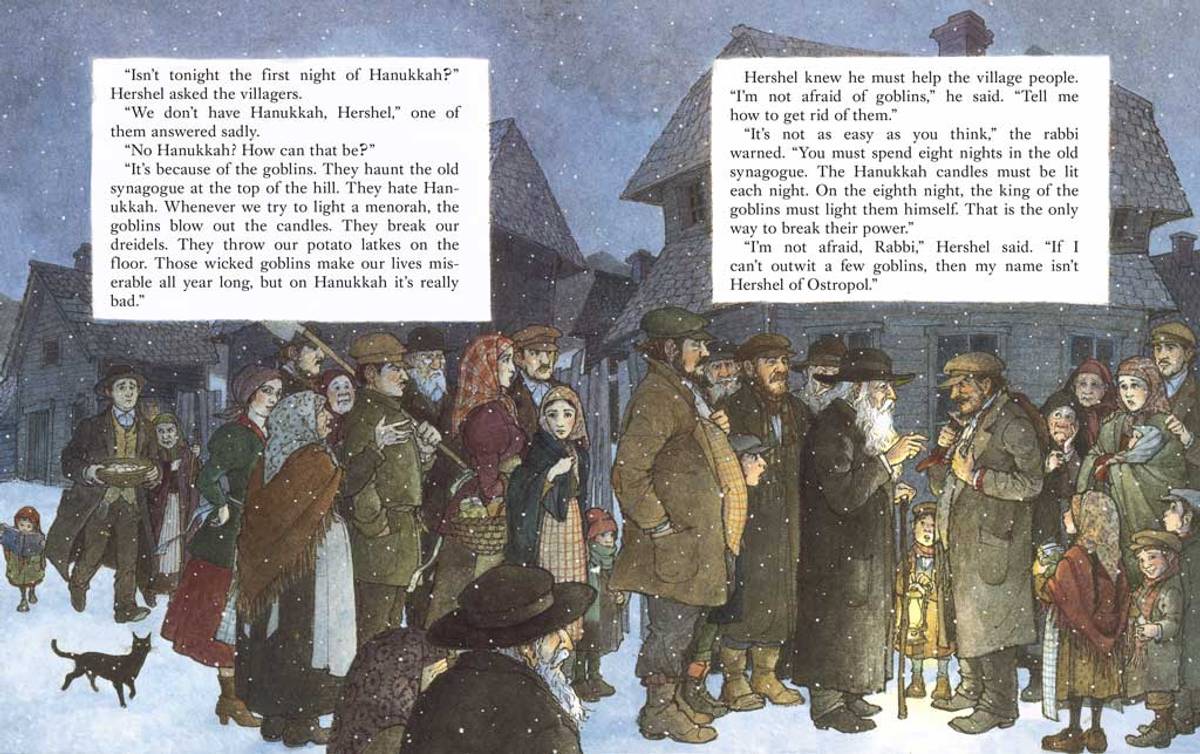

Hershel and the Hanukkah Goblins remains Kimmel’s master achievement. (So far.) A Caldecott Honor-winner, with unnerving illustrations by the late, great Trina Schart Hyman, the book celebrates its 30th anniversary this year. It tells the terrifying tale of a tiny shtetl haunted by eight goblins. No one can light even a single candle because of them. But when humble yet clever traveler Hershel Ostropoler comes to town, he vanquishes the goblins one by one. I cannot express to you how awesome this book is, and I’ve tried numerous times over the years, so let’s skip to the happy ending when you buy it.

But why is Kimmel all alone out here, like the final girl left alive to face the killer in Halloween or The Texas Chain Saw Massacre or Friday the 13th or A Nightmare on Elm Street? Why isn’t there a robust world of Jewish horror for kids?

Sure, there’s Isaac Bashevis Singer’s Zlateh the Goat, which features seven Chelm stories—some funny, some scary. But it’s from 1966, and (again, sorry not sorry) is a little wordy for today’s audiences. The extremely frightening illustrations by Maurice Sendak, however, hold up. Even Sendak’s funny work has a hint of scary, and when he goes full demon—whipping up a shadowy, cross-hatched, bulbous-nosed, goat-footed, beetle-browed and Gene-Simmons-tongued creature—he makes the Wild Things look like the Berenstain Bears.

In quality spookiness, there’s 2013’s The Path of Names by Ari Goelman, about a girl at Jewish summer camp who gets swept into a Kabbalah-infused mystery, and 1976’s The Rabbi and the Twenty-Nine Witches by Marilyn Hirsh, about a small town that’s bedeviled by witches every nonrainy full moon until the rabbi figures out how to trick the witches into self-destructing. (Hirsh died at 44 in 1988—what other stories might have she come up with?) Both books are out of print. At least The Entertainer and the Dykkuk, by the late Sid Fleischman—an unnerving tale of a ventriloquist possessed by the spirit of a boy murdered by the Nazis—is still in print, and still a very weird mix of humor and horror.

And sure, there have been a number of excellent, unnerving books for kids about the golem. I did a roundup in 2011 of a bunch of options and the reasons for the dirt monster’s enduring popularity. But there haven’t been many great additions since then. The ones you need are still Golem by David Wisniewski; The Golem by Isaac Bashevis Singer, illustrated by the brilliant Uri Shulevitz; and The Golem of Prague by Irène Cohen-Janca, illustrated by Maurizio A.C. Quarello. They’re all for tweens, because the source material is frightening as hell. That’s what makes them good! Cute golem stories exist (including one by Kimmel) but I don’t want my golems cute. The Maharal of Prague source material is a repository for all kinds of fears about anti-Semitism, parenthood, childhood, loss, lack of control, the seductive power of creating chaos and destruction; there’s a reason it’s fueled superhero comics (an art form infused with Jewish history) and young adult novels (which wrestle with identity, appetite, and id). Not cute.

Golems aside, there’s tons of legit scary stuff for little kids. It’s just not Jewish. My own children’s elementary school librarian, Cheryl Wolf, finds that scary books are so in demand that she puts little black stickers with the word SCARY (along with an illustration of a pair of yellow eyes with red eyeballs) on the spines of qualifying titles so kids can more easily find them, and she puts them on low shelves in colorful bins. “It’s all about ease of access,” she told me in an interview. (Some librarians object to bins, feeling they prevent kids from learning the Dewey Decimal System. But Wolf joked that she was going to make buttons that said, “I read binned books.”)

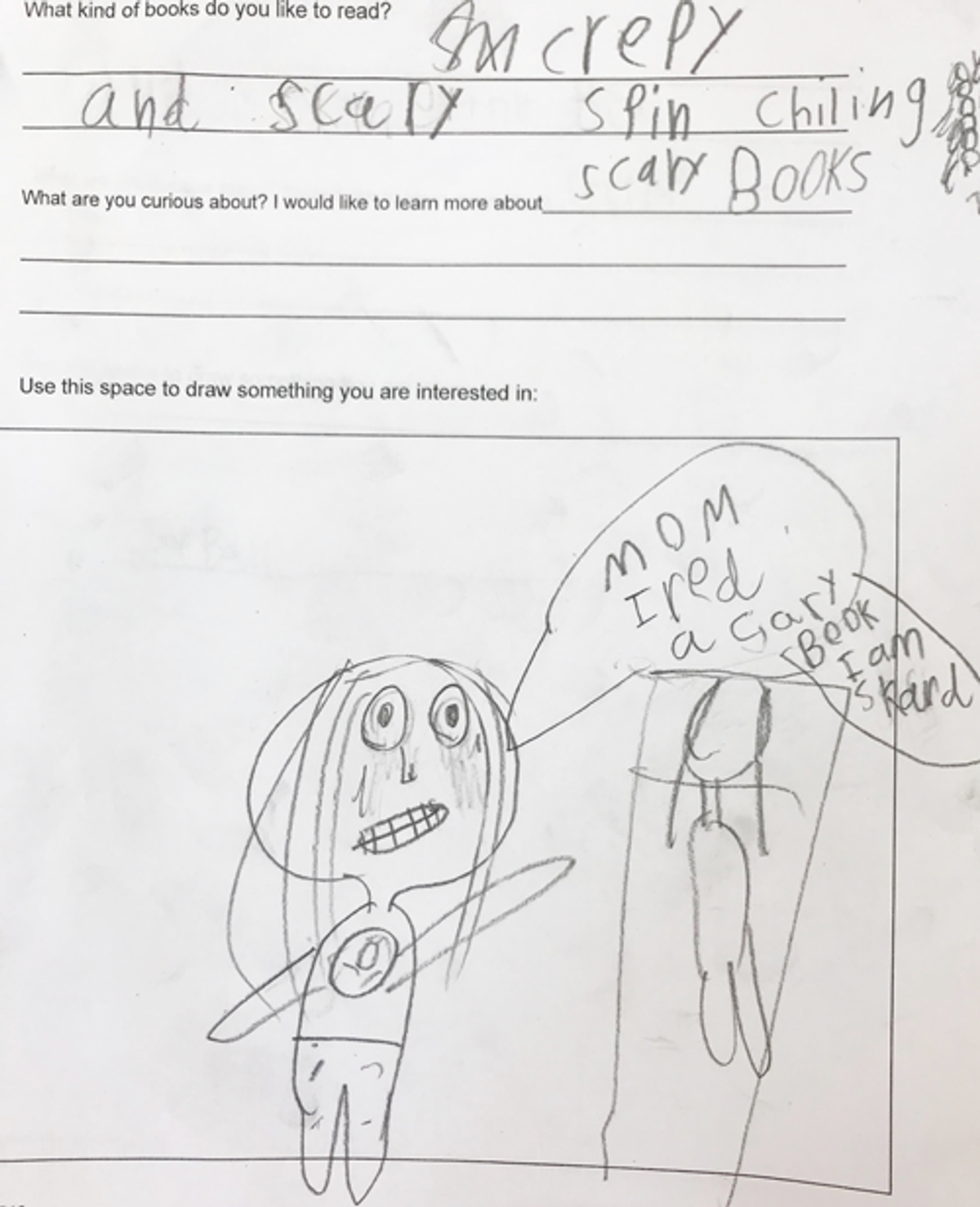

Why is scary so popular? “I’m reluctant to psychoanalyze, but Bruno Bettelheim’s theory is that reading horror is a way for kids to cope with their own fears,” Wolf said. “There’s pure exhilaration along with the fear—you’re conquering it.” She provided me with a library survey she produced in which kids told her what they wanted: “Crepy and scary spin chiling scary books,” one kid wrote, adding a helpful illustration of a spine. (A bunch of stacked little balls in a vertical line with emphatic zigzags all around them.) One little boy told her in person, “I like to freak out and shiver. I imagine I’m in the book and I’m brave and scared at the same time.” Another said, “I love to get terrified. I like to retell the story [to my little brother at bedtime] and make it even scarier.” Wolf’s elementary-age readers are not messing around: “They want real-scary and won’t be fooled by cute-scary,” she said.

“Graphic novels and scary are the two top categories kids want,” she went on. “One of the most popular books in the library is an Alvin Schwartz book in ‘I Can Read’ format. It has the velvet ribbon story. I like to read that one aloud.” A series called “Eerie Elementary” is also popular. “I’m always looking for what’s called ‘high interest, low level,’” Wolf said—easy-to-read books with gripping plots and fun illustrations for kids who aren’t superaccomplished readers yet. “There is so much fear in our lives as adults,” she said, “But it’s abstract to most kids; it’s not a real threat. I want to read funny books and see funny movies, especially right now, but kids are immune to that. Thankfully.”

Given how popular scary books are with kids, though, the paucity of Jewish horror is odd. (Yes, Alvin Schwartz and R.L. Stine and arguably Neil Gaiman are Jews. But being Jewish isn’t synonymous with telling Jewish stories.) Sylvie Shaffer, an elementary school librarian and current Sydney Taylor Book Award committee member in Washington, D.C., posits, “Maybe there’s a market gap because we do have so many horror stories—they are Shoah stories.” Indeed they are.

But maybe there’s also some self-censoring and unexamined self-hatred going on in publishing. Diversity advocates who don’t include Jews in diversity initiatives often argue, behind closed doors, that Jews don’t need representation, and that there are tons of us working in publishing. But Kimmel told an illustrative story to Publishers Weekly on the occasion of Hershel’s 25th anniversary in 2014: “None of the Jewish editors would touch it,” Kimmel recalled. “They thought it was just too far out. … It’s interesting that in the end, the only Jewish person involved with this was me.” The book was published because Marianne Carus, the non-Jewish editor of the children’s magazine Cricket, wanted to run a Hanukkah story and asked Kimmel if he had one. She assigned the artwork to Hyman. Hyman loved the story so much she asked her editor at Holiday House to publish the book. And the rest is history.

Maybe Jewish editors don’t think the wider world would be interested in Jewish stories. But Esme Raji Codell, author of How to Get Your Child to Love Reading: For Ravenous and Reluctant Readers Alike (an extremely helpful resource in my own parenting), noted, “A good story belongs to everybody.” Again I beg: Include our stories in your diversification efforts, everyone.

And maybe not enough Jewish writers know enough about Jewish folklore. There are tons of Jewish demons, dybbuks, and diabolical monsters who haven’t appeared in children’s literature at all. The Encyclopaedia Judaica entry on Jewish demonology reads like the entire run of Buffy in one page. Berakhot 6a, in the Talmud, describes houses of learning as full of demons when sexual energy isn’t properly channeled. (Maybe save that plot idea for your young adult novel.) Raba said of demons, “Fatigue in the knees comes from them.” (I have demons! I thought it was bursitis!) Rav Huna said, “Every one among us has a thousand on his left hand and ten thousand on his right hand.” Haunted by invisible supernatural tormenters? Berakhot suggests, “If one wants to discover them, let him take sifted ashes and sprinkle around his bed, and in the morning he will see something like the footprints of a cock.” There you have it.

There are dozens of shedim (evil spirits) and mazzikim (demons—my dad used to call Josie a mazzik when she was being naughty, because in its Yiddish usage, it’s an affectionate term for a playful little demon) to choose from. There are also many tricks to avoid summoning these creatures, like refraining from whistling or even saying their name aloud; the latter is the equivalent of looking in a mirror while saying CANDYMAN CANDYMAN CANDYMAN. We may be short on books, but the third episode of a brand-new WGBH children’s podcast called The Creeping Hour spotlights shedim. The show is No. 1 in Apple Podcasts’ kids section; The AV Club said it “evokes the feeling of a midnight campfire tale on a chilly autumn evening.” It does! (Still, pro tip, I suggest starting to listen at the 2:54 mark; my kids wouldn’t have sat for the scattershot first three minutes. I promise it gets spooky when the actual story kicks in.)

In Halloweens to come, I hope we’ll have more scary Jewish stories to tell in the dark. Even if I have to look into a mirror and chant Aramaic and Hebrew demon names to get them here.

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.