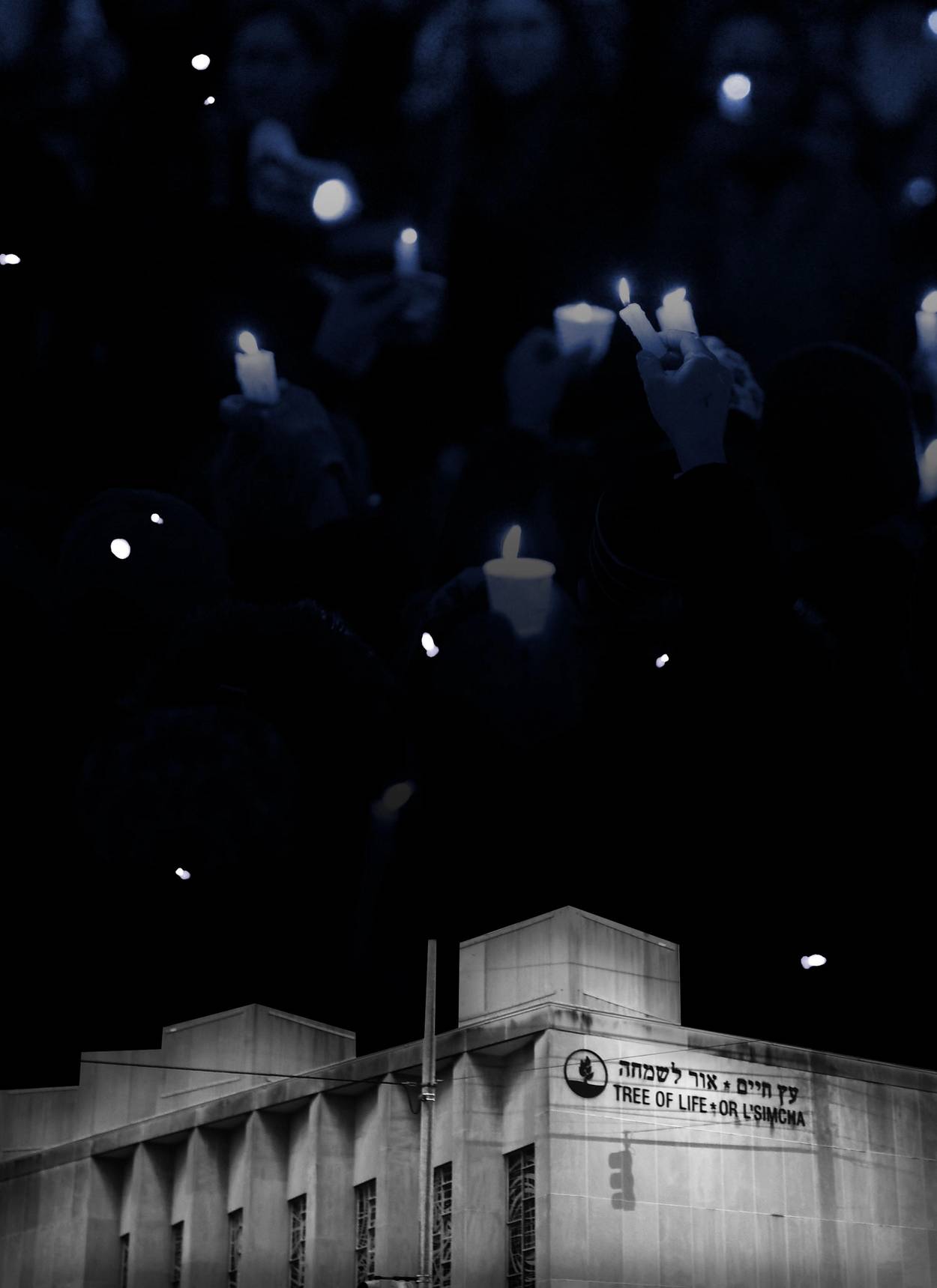

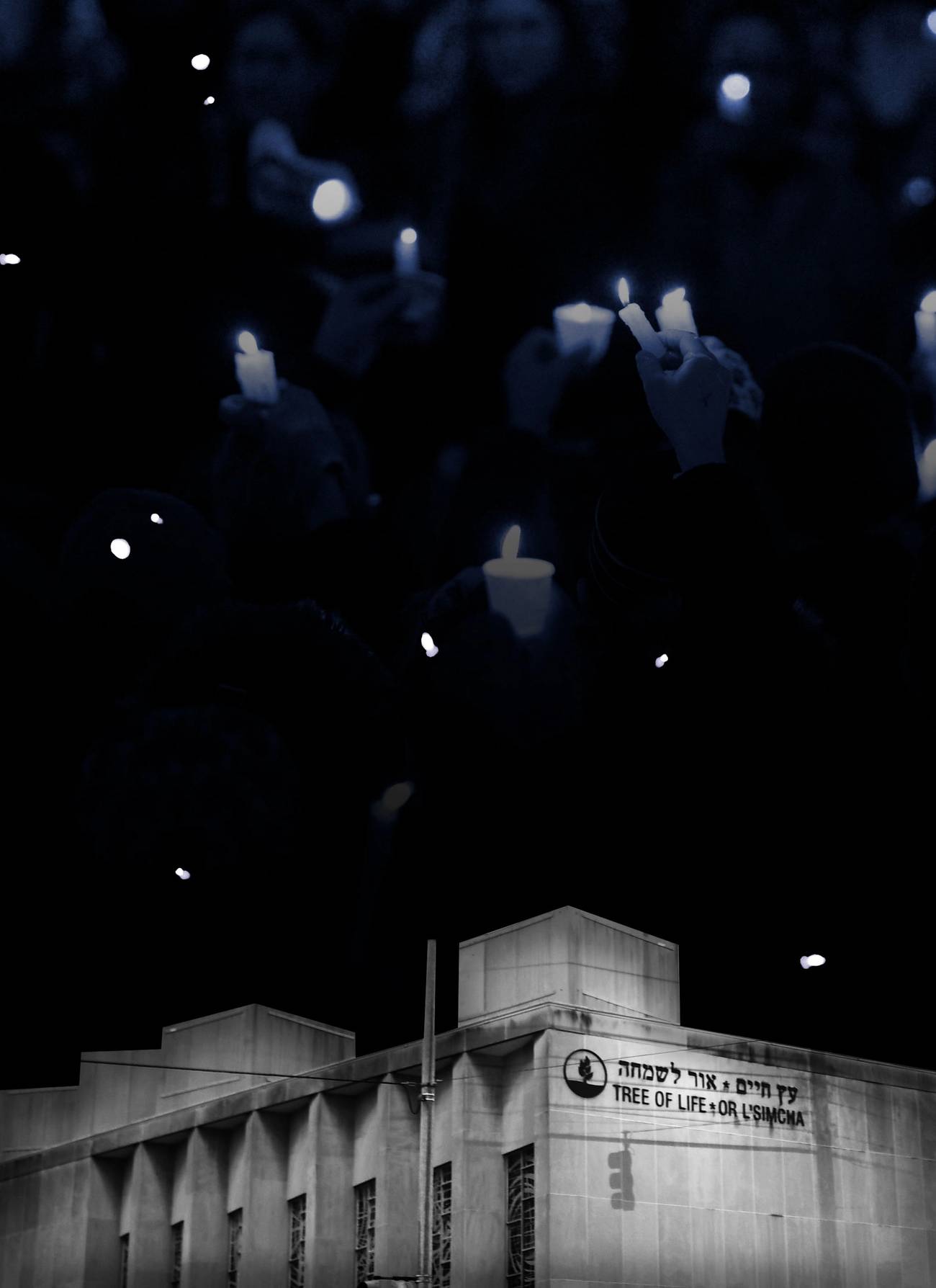

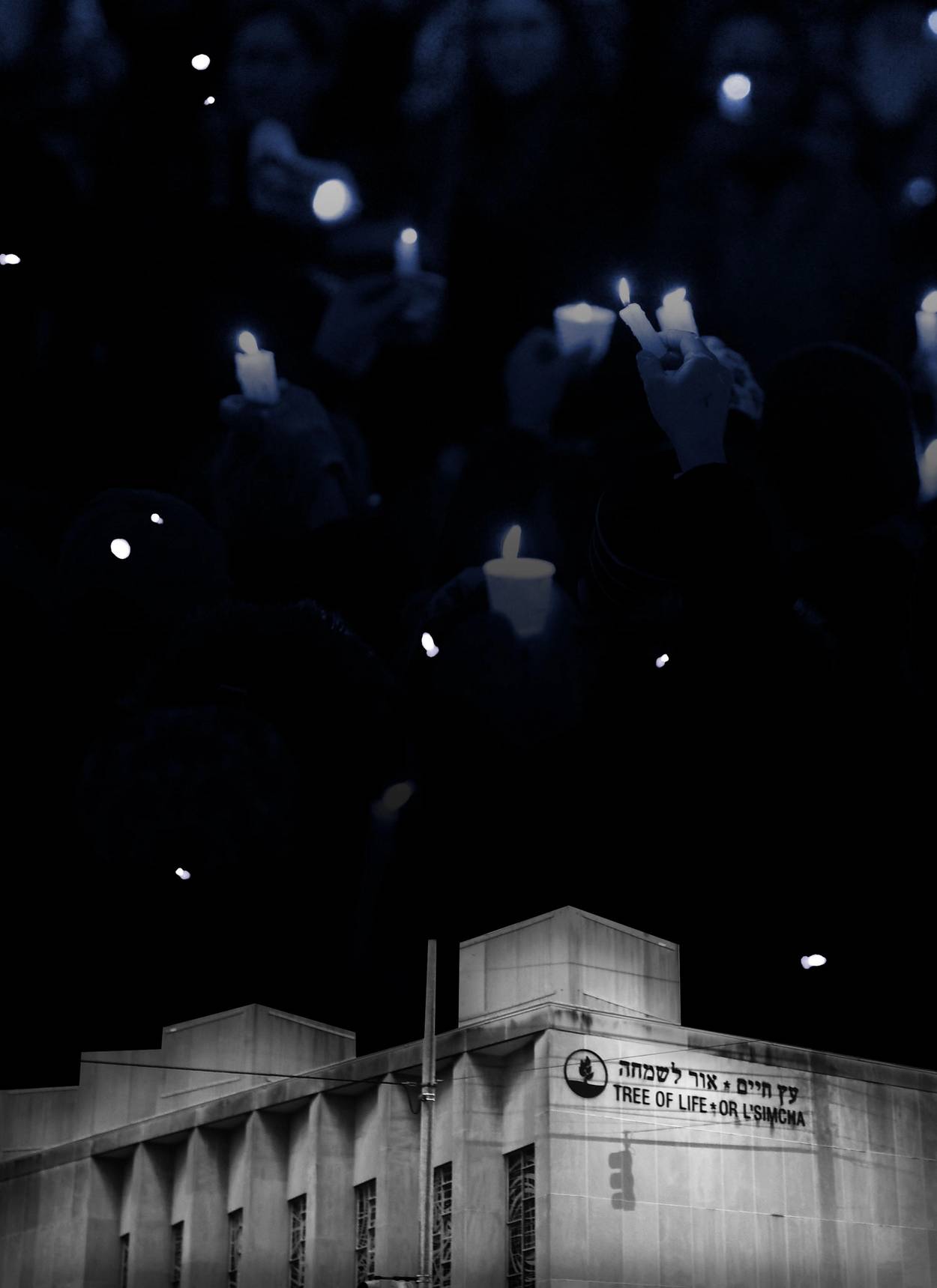

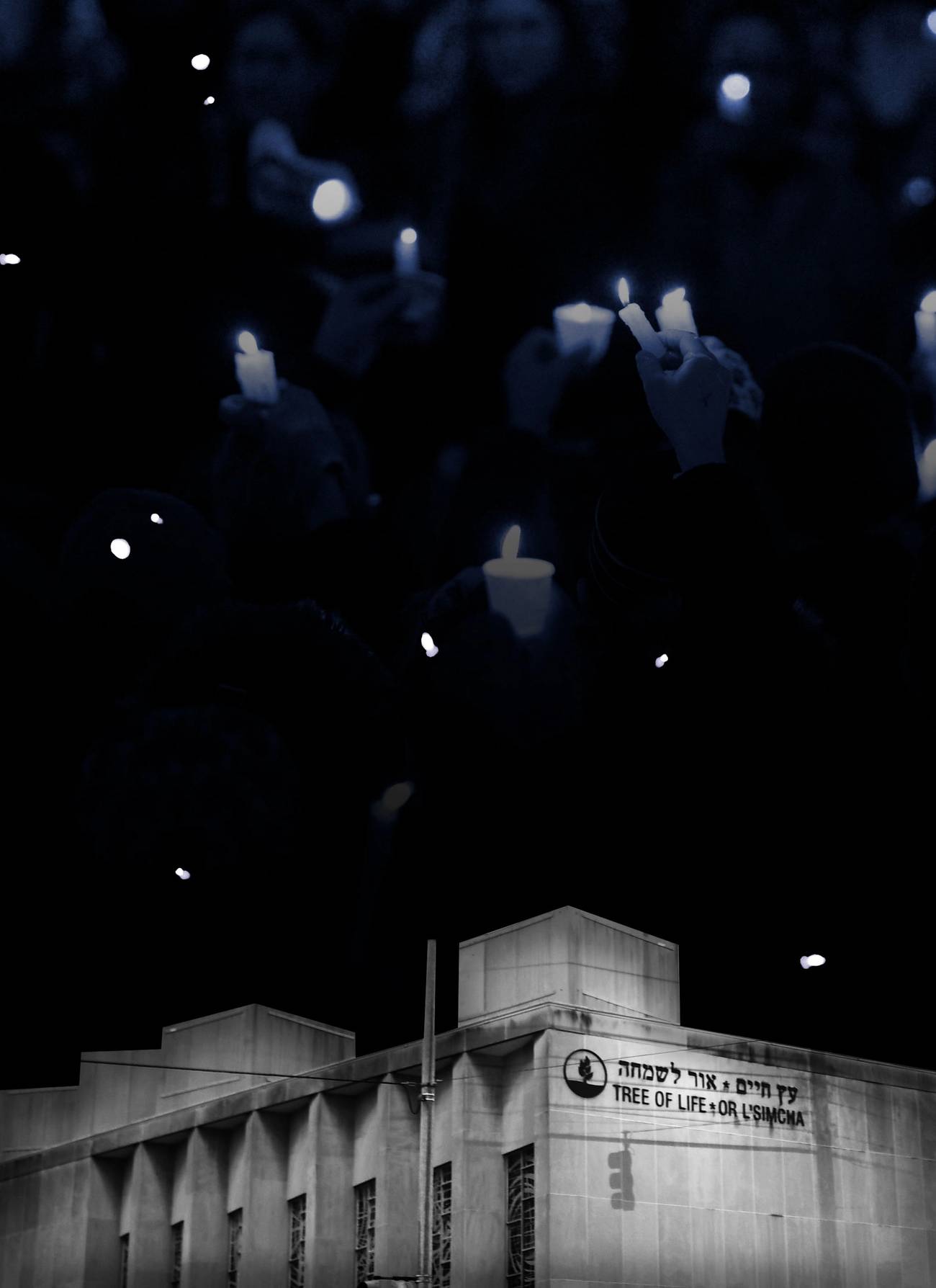

Shocked, Not Surprised

On the anniversary of the Pittsburgh synagogue shooting, remembering the violence that shattered a community

In October 2018, a new friend, Roz, said to me, “Come to services Friday—it’s my birthday!” I readily went to Friday night services at our synagogue, Dor Hadash. The service on Roz’s birthday was joyous. About 60 people attended, I’d guess, in the long pavilion of the Tree of Life complex in Squirrel Hill. A cheerful rabbi visiting from Oregon, “Rabbi Yitz” (Yitzhak Husbands-Hankin), played his guitar and gave a talk. A member of the congregation ended the service by calling for a blessing on all the people (pointedly including the Arab population) in Israel and the territories. And after the service there was birthday cake for the Oneg Shabbat (rejoicing in the Sabbath) in the glass-walled corridor of the building.

If I had to describe Dor Hadash in one word, it would be “welcoming.” Luckily, I’m allotted more than one word. Nonhierarchical. Open. Engaged. Inquiring. Dor Hadash has a DIY ethos—since its founding it has been led not by a rabbi but by lay members. Members decide on ritual, members chant from the Torah, members provide snacks. Nonhierarchical: Once, when I was to provide food for the Oneg Shabbat, the refreshments for “rejoicing in the Sabbath,” the cantor realized that the attendance would be extra large, and she came early with home-baked goods and helped me set the tables. Open: At any given service you might see women in colorful tallits and head coverings, non-Jewish spouses and partners, same-sex couples, Jews by birth and Jews by choice, sometimes even the Kilt Man, in his neon-colored kilt and contrasting stockings. Prayers that refer to our fathers Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob also include our mothers Sarah, Rebecca, Leah, and Rachel. Dor Hadashers don’t have to affirm belief; members may be “uncomfortable with G-d language.” Engaged: The popular Social Action Group was working on two concerns that year: criminal justice, and refugees and immigrants. Inquiring: Dor Hadash was founded as a study group. On Saturday mornings a group convenes for study of the Torah, and the talks (we don’t have sermons) are often probing and scholarly. Welcoming: At the High Holy Days, when many Jews who don’t attend synagogue at any other time wish to attend services—and when many if not most synagogues limit attendance to paid-up members—Dor Hadash traditionally is open to all.

At about 10:20 on the morning after that joyous Friday night service, my brother called from New York. My husband answered the phone. “There’s been a shooting at Tree of Life.” And we were not to leave the house. “Shelter in place”—a phrase that seems routine during these days of COVID-19.

We didn’t immediately know what had happened. Strangely, while I’d been at services Friday my husband had figured out how to use the TV remote, since we had received three months’ free service from our cable company. That Saturday we were glued to TV for news. We knew there had been a shooting, but little more. When we knew that there had been fatalities, we waited to find out how many and who. My cousin Claudia called from California, hoping to find out whether her aunt’s nephews, two men with developmental delays, were alive. “The boys” were familiar faces in our neighborhood—one broad and friendly, one thin and more skittish, anxious. They used to like to visit the fire station. They went to Tree of Life faithfully.

The news came in. Cecil and David were dead. Joyce Fienberg was dead, a friendly woman I knew because we both had worked in the same institute at the University of Pittsburgh. Jerry Rabinowitz was dead. Jerry … There’s a saying in Pirkei Avot, “Where there is no mensch, be a mensch.” “Mensch” meaning not “man” in the macho sense, but “human being.” Humane being. Jerry was that. About a month before the shooting I was one of the congregation members whom Jerry organized to get the once-a-year High Holiday books out of storage, a mundane task. Big books, to be taken out of the closet, unpacked, and put on carts. I understand that on Saturdays Jerry set up the room for the Torah study group, filling juice cups and putting them out. Possibly that’s what he was doing on that Saturday. He was there early for that reason. Some physicians have an elite aura—you would never know that he was a doctor. I heard (later, later) that he was beloved by many for having treated patients with HIV during the peak of the AIDS crisis, holding their hands with his own ungloved hand. Another mensch, a mainstay, one of the founders of a group for the compassionate care of the dead, and I think the man who invoked the blessing of peace for all the inhabitants of Israel, was grievously wounded. A woman and six of the police who responded were wounded. The shooter was wounded. On that Saturday morning 11 of the congregants of three congregations were killed—killed by a weapon of war.

The shooting tore the fabric of a beloved community. I wrote shortly afterward: “I have been feeling my emotional bones, wondering why they are not broken. Why I am not shivering and crying. Am I hard-hearted?” No. I’m not hard-hearted. I’m not inured to violence. Rather, both my personal and historical memory make me conscious of the possibility of violence and the possibility of anti-Jewish acts. As a Jew of a certain age I have never felt completely secure. I grew up in New York, my immediate neighborhood predominantly Irish. On the street near my apartment house, where we played jump rope and ball-bouncing games, I was not entirely at ease. My neighbors all went to Catholic school and I went to public school, which made a difference between us. But I was known and knew them. A little further away in the neighborhood I might be bullied and taunted by strangers. At school I was at ease. Some of my classmates were the children of Jewish refugees from Europe. We were children; I didn’t know what that meant, but I learned later. I’m conscious of past and present anti-Jewish feeling and actions, and I’m conscious of past and present gun violence. So when the shooting happened, I was shocked, not surprised.

Tree of Life

I marked myself safe on Facebook

when the alert came: active shooter

in my neighborhood.

Is safe a lie if you want to believe it?

I never feel safe.

When I was eight my playmate Patsy

came home from her school

and asked me Why did you kill Christ?

I had no answer.

Ambushed by strangers

near the synagogue,

I spilled my Hebrew-school books,

their top-heavy black letters.

At Hallowe’en I defended

my kid brother, socked with nylons

full of powdered chalk,

his jacket marked, unsafe.

I saw a movie of bulldozers

burying skeletal dead.

Shelter in place, the notice said.

My friends and neighbors text,

and I tell you: Stay safe.

I think I hope to harden myself against bad news by expecting it. Knowing that human life and luck are contingent—a frequent theme in my poetry. I know that there are many people who believe otherwise, that all is the Creator’s plan, every sparrow’s fall. Not long before the shooting, during the High Holy Days, we read, “On Rosh Hashanah it is written, and on Yom Kippur it is sealed, who shall live and who shall die, who by fire and who by water ...” and a litany of possible fates. Who shall be torn by wild beasts. Which perhaps is what happened at Tree of Life. The beast of ignorance, the beast of rage.

In the months before the shooting, signs had bloomed in the yards of my neighborhood: You belong here. No matter where you are from, we’re glad you’re our neighbor. Many of the signs were multilingual, in English, Spanish, and Arabic, in implied contrast to the Trump administration’s actual and proposed restrictions on immigration and asylum. The man accused of the Tree of Life shooting had written posts that indicate that, in addition to his anti-Jewish feeling, he targeted Dor Hadash because we had had a refugee Shabbat—a service to remind people of the worldwide refugee crisis. He was not—explicitly not—a Trump supporter, but no doubt he had imbibed the panic being whipped up by the president about immigration and the “caravan” of likely asylum seekers. He has been quoted as saying, “All Jews must die.” He shot his way into the building through the glass wall of the pavilion where we had had cake the night before.

A high school student who was one of the organizers of a massively attended vigil on the Sunday night after the massacre said she didn’t think this could happen here. But it did. And I remembered that it had happened before, in Pittsburgh, though not on this scale. In 1986, in Squirrel Hill, a white man in a car asked Neal Rosenblum, a visibly Jewish man, for directions. Rosenblum was a young Canadian father who had just arrived in Squirrel Hill for a Passover visit. The man in the car shot him five times. Rosenblum survived long enough to speak to emergency workers, but died in the hospital. In April 2000 a racist white man, Richard Baumhammers, shot and killed his 63-year-old Jewish neighbor, threw a Molotov cocktail into her house, then drove around for two hours shooting, one by one, four people of Asian descent and a Black man. He also vandalized two synagogues. He did not shoot the white man talking with the Black man. All but one of the victims died. The survivor was paralyzed and died at age 32. Also in spring 2000, Ronald Taylor, a Black man who’d expressed hatred of white men, shot five white men at random in Wilkinsburg, a town adjacent to Pittsburgh. In 2009 George Sodini targeted women at a fitness studio in Collier Township, 10 miles south of Pittsburgh. Three of the women died, nine other people were injured, and Sodini committed suicide.

It’s horrifying. It’s horrifying when it happens at a school, it’s horrifying when it happens at a church, it’s horrifying when it happens at a Sikh temple, it’s horrifying when it happens at a nightclub. It’s horrifying when it’s routine, when “only” two people are shot and it is hardly noticed. Close to the time of the Tree of Life shooting a man in Kentucky tried the doors of a Black church, found them locked, and went to a store and killed two Black people. The congregations at Tree of Life opened the doors to worshippers Saturday morning. And Death entered by shattering the glass walls.

Time and distance attenuate our attention and compassion, as I suggest in a poem I wrote after the Virginia Tech massacre in 2007. Thirty-two people were killed there and many more injured. The shooter had the advantage of semiautomatic weapons.

Nearer

All day our brilliant screens show without letup

hysterical screamers winning money prizes,

a woman sneering at another’s getup,

boys doing jackass stunts in various guises,

in aspiration to become well known.

A reporter poses before a green setup

and picturesque, a foreign ruin rises.

A war somewhere, an earthquake. No surprises.

But images now, sent from a cellphone,

show kids you know shooting, shot, dead! Alone

on the sofa, God sleeps through these dull affairs,

this noise, while darling Pity watches Terror

caper and tap dance up and down the stairs.

Not long after the Tree of Life shooting, Brad Orsini, then the director of security for the local Jewish community, a former FBI man, taught a “security training” session, very well attended, for members of Dor Hadash. As part of the training, we saw a short film of people in an airport immediately after a gunman opened fire. One man froze, standing, a perfect target. Sometimes people run, but collect in one place, also making slaughter easy. Orsini told us that the Department of Homeland Security has worked out a simple-to-remember formula for active shooter situations, a phrase that they hope to make as familiar as “Stop, drop, and roll” in case of fire: “Run, hide, fight.” Are children in school learning this now?

Security Training—Stop the Bleed

The US Department of Homeland Security advises remembering: “Run, Hide, Fight.”

Run. Escape if you can.

Walk across Russia to Austria.

Get on a train to Rotterdam.

Emigrate to Cuba, which has an unfilled quota.

Hide. Shelter in place.

Shave your beard, bleach your hair.

Get a nose job.

Change your name.

Fight. As a last resort.

Look around you—everyday objects

can become weapons. Hot coffee. Pencils.

Throw accurately and with force. Strike

without apology.

Run. Hide. Fight.

Never again. Again. Again.

After the shooting there was a tremendous outpouring of ceremony and acknowledgment within Pittsburgh and from around the world. Television stations set up canopies in a literal encampment around the site. Signs saying Hate Has No Home Here appeared in store windows and on lawns. That I doubt (as Black people will tell you), but it’s an aspiration, a hope. And the people, the wonderful people, who are a community, supporting each other, give me hope.

Excerpted from Bound in the Bond of Life: Pittsburgh Writers Reflect on the Tree of Life Tragedy, edited by Beth Kissileff and Eric Lidji, copyright 2020. All rights are controlled by the University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, PA 15260. Used by permission of the University of Pittsburgh Press.

Arlene Weiner is a poet and playwright active in several poetry groups in Pittsburgh. She has been a Shakespeare scholar, a college instructor, a cardiology technician, and an editor. Ragged Sky published two collections of her poetry, Escape Velocity and City Bird. Arlene earned her PhD in English and American literature at Brandeis, and has held a fellowship to the MacDowell Colony.