Shouting Into the Void

Why I finally decided to learn Yiddish

Someone once asked me why I—a lover of all things Jewish and a student of languages, from Portuguese to Hebrew to Spanish and French—had never studied Yiddish. I raised an eyebrow. “What for?” I replied. “What country could I travel to where Yiddish is used? Whom would I even practice with? No one speaks Yiddish anymore except for the ultra-Orthodox. It would be like shouting into the void.”

When I was growing up on Long Island in the 1960s and ’70s, Yiddish was the language spoken by Jewish parents when they didn’t want their kids to understand. (“Sha, di kinder,” they’d shush each other.) Yiddish was also a bunch of funny-sounding words parents sprinkled into their mostly English conversations in the kitchen and the car and at family bar mitzvahs.

For my generation, Yiddish was also a remnant of the world our grandparents left behind when they emigrated from Eastern Europe in the early 1900s: the slightly mournful language they spoke when they were alone with each other, and whispered in synagogue to the other old people, and used to write increasingly infrequent letters to the relatives left behind. Yiddish was a dusty old artifact in a dusty old museum cared for by a bunch of dusty old curators. The language was disappearing, and young Jews met it with disinterest and complete and utter silence.

For years I was as guilty as the rest, until the contents of an old cardboard box showed me a new way to think about the language.

The word for “Yiddish” in Yiddish is mameloshn—“mother tongue.” But Yiddish was not my mother’s mother tongue. That was English, the language she spoke to her parents and the language in which she and my father raised my brother and me. But if English was my mother’s mother tongue, mameloshn was her spirit tongue, the language of her heart. It reminded her of growing up in Brooklyn in the 1930s and ’40s, evoking a time when everyone’s parents had an accent and every kid drank in mameloshn with their mama’s milk. She would pepper her sentences with colorful Yiddish words, some of which I came to understand: farbissener to describe a difficult, implacable neighbor; strashen when she’d tell me how a woman on one of her committees made idle threats; and, to show that not all Yiddish words described unpleasant situations, a mechayeh, something that revives your soul, like chicken soup on Friday night or lowering yourself into a warm bath.

But most of the Yiddish words and expressions she used meant precious little to me and were not much more than background noise. As I grew up, I’d sometimes hear a Jewish comedian use a word that I remembered from my childhood and I’d smile, but that was it. No teary-eyed memories, no deep emotional ties.

Thirteen years in Israel made my attitude toward Yiddish even harsher. The founding Zionist fathers were convinced that Yiddish would just not do in the new Jewish State. Yiddish was the language of the Diaspora, of the weak ghetto Jew killed in pogroms and in gas chambers, not of the strong, proud Israeli reviving the ancient tongue of the Bible in the ancestral homeland. Hebrew would be the language of the new Jew; Yiddish was for the Exile (galut in Hebrew and not, repeat not, galus in Yiddish).

Yiddish was shunned and stigmatized in the first decades of Israel. There were few Yiddish books published, almost no Yiddish theater, and even a Battalion for the Defense of the Hebrew Language. Israeli children would turn with pleading, humiliated eyes to their Yiddish-speaking immigrant parents in the supermarket or the post office and beg, “Please, please speak Hebrew!”

Living in Israel in the 1980s and ’90s, I readily absorbed this stigma. “Hebrew is the language of the Jewish People,” I parroted rather smugly. “The language of the Torah and the Prophets and of the Golden Age of Jewish Philosophy. Study Yiddish? It’s like shouting into the void.”

But then I started reading about the revival of Yiddish around the world. The young and hip, members of the LGBT community, radical poets, and the heavily tattooed and pierced were rushing to study the language in droves. Trendy restaurants sprouted up around the world with Yiddish names and bilingual menus; in the hipster neighborhoods of South Tel Aviv, I saw that the graffiti was mostly in Yiddish.

For some, learning Yiddish had become a form of social protest to identify with the underdog; for others, an alternative door into Jewish culture that avoids the complexities of Israel; and for still others, it’s simply a longing for bubbe and zayde. Whatever the reason, I saw that Yiddish was finally so far out, it was in.

I also remembered that it was in mameloshn that my mother first communicated with our long-lost relatives in Latvia. Just before I traveled there in 2002, I bought a black mini-cassette recorder and had my mother tape a short Yiddish message for Zalman, my grandfather’s oldest surviving first cousin. A few days later, I sat in in Zalman’s small apartment in Riga and pushed “play” on the black recorder. I heard my mother’s voice: “Ich bin dayn kouzineh Phyllis Weinstock. Ich hob a man un tsvey zin.” (“I am your cousin, Phyllis Weinstock. I have a husband and two sons.”)

Cousin Zalman’s eyes lit up. He taped a short message into the recorder and handed it back to me. “Far der mamen,” he said. (“For your mother.”) I didn’t understand anything else he said, but I suddenly saw that the mother tongue had worked, up close and personal. Maybe Yiddish was good for something.

In 2015, I saw a Facebook ad: “Come study Yiddish at Tel Aviv University this summer!” By that time, my mother’s tongue had been silenced for five years by a stroke. Her communication slowly declined until she could only mouth words or pantomime. And then she died, taking with her the last tangible link I had to Yiddish.

And so, on a whim, I joined 109 other students at the monthlong course in Tel Aviv, four hours a day, five days a week. We had homework—grammar drills and compositions every night—along with a weekly exam. It was extremely demanding and very, very challenging, even for a language lover like me.

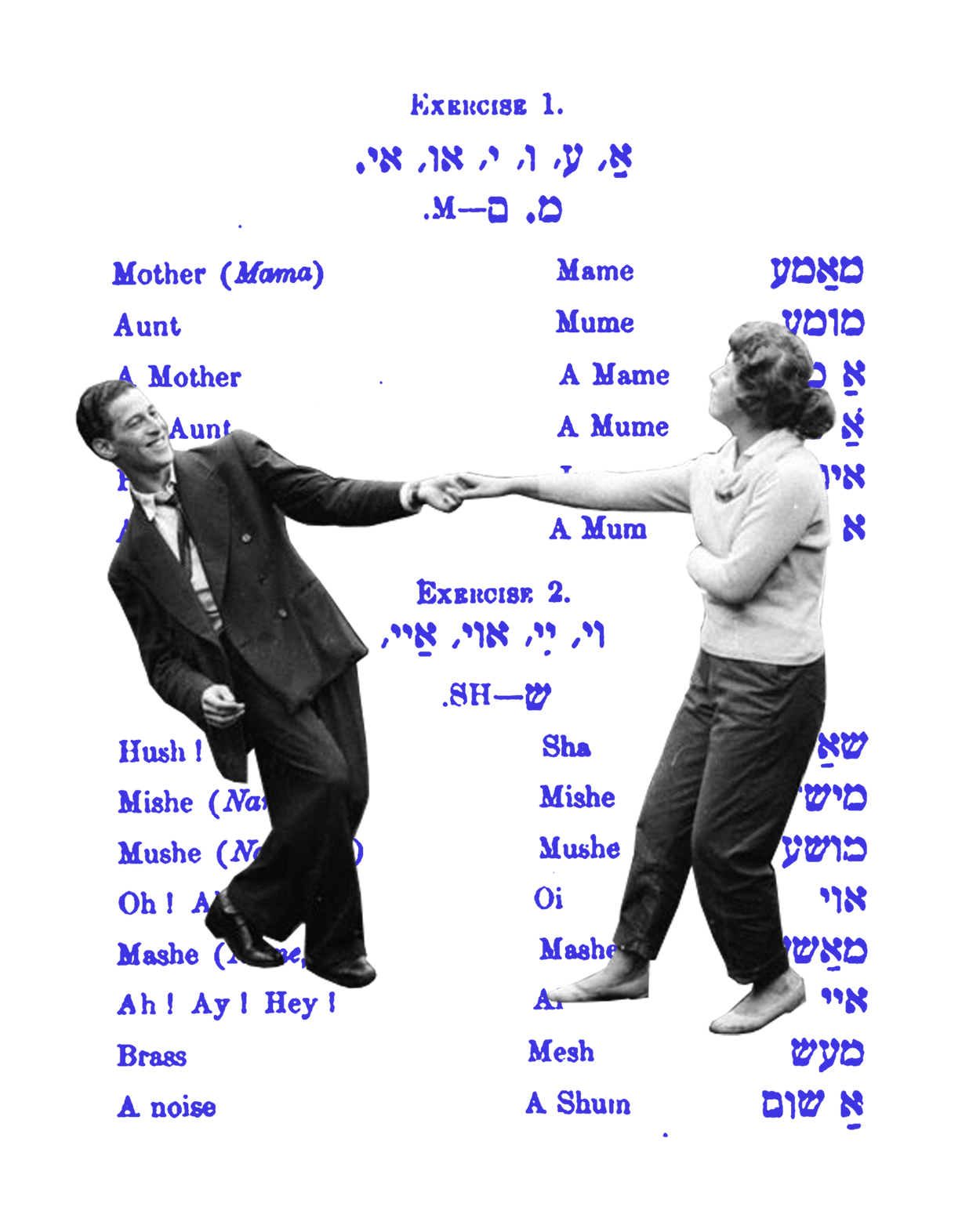

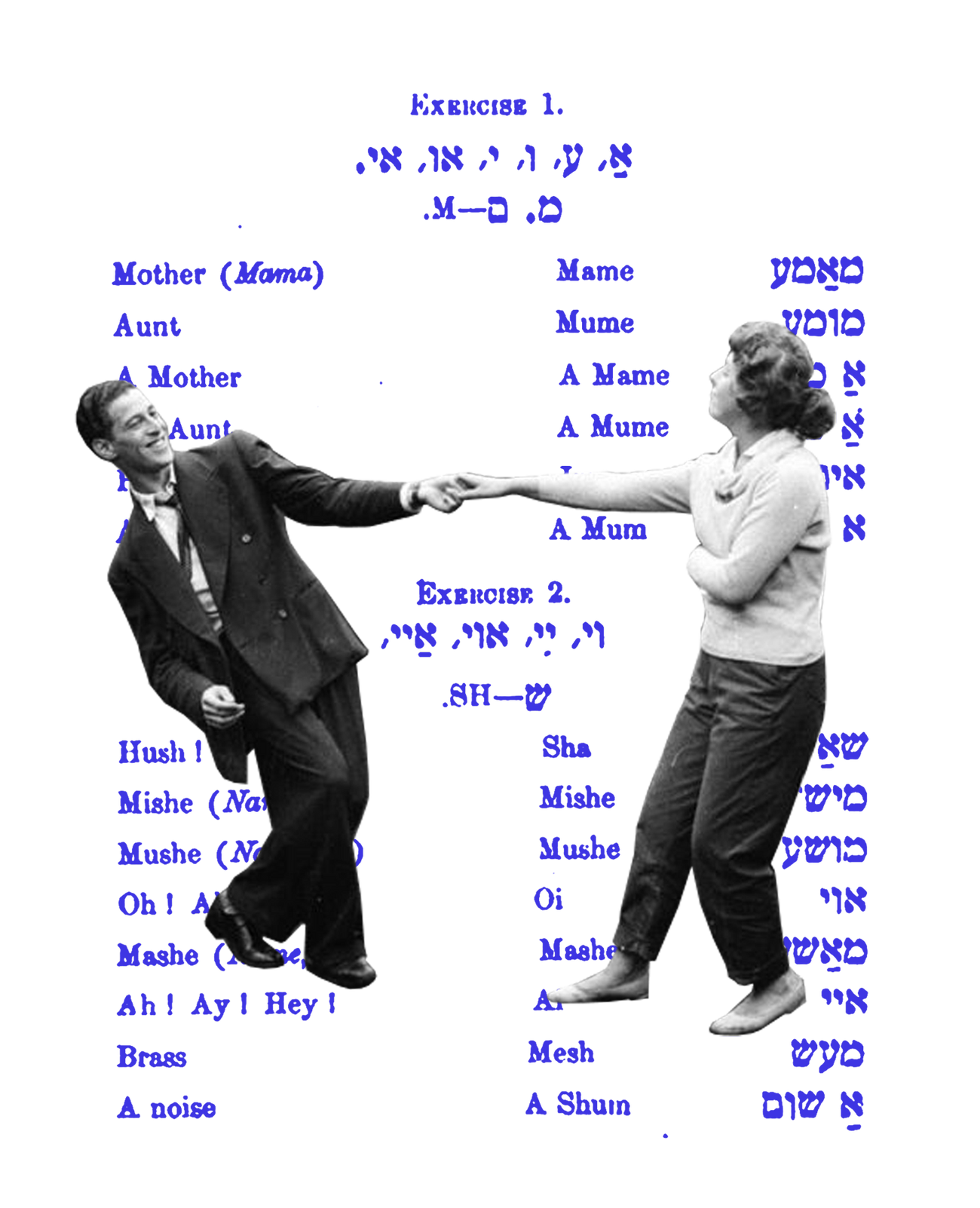

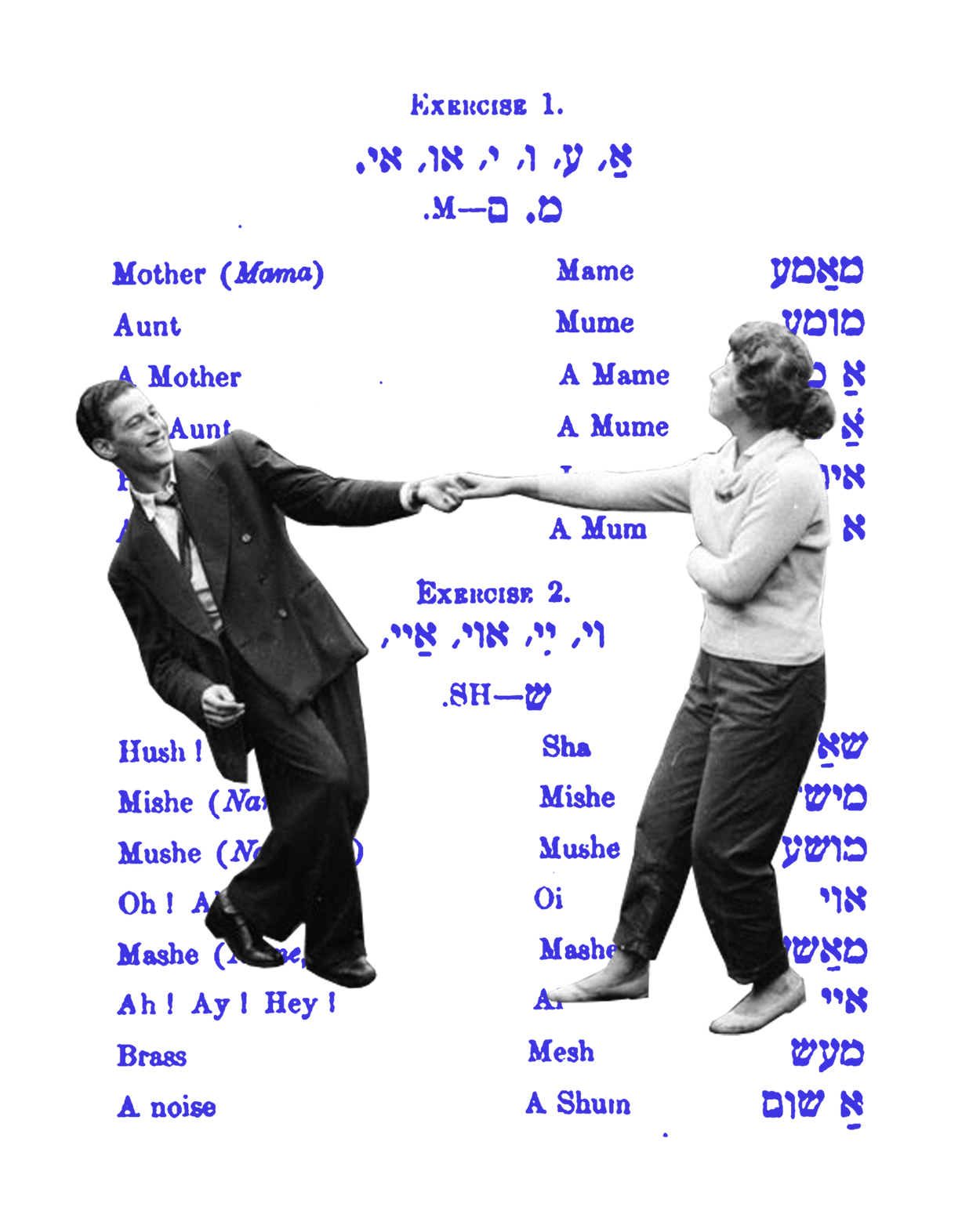

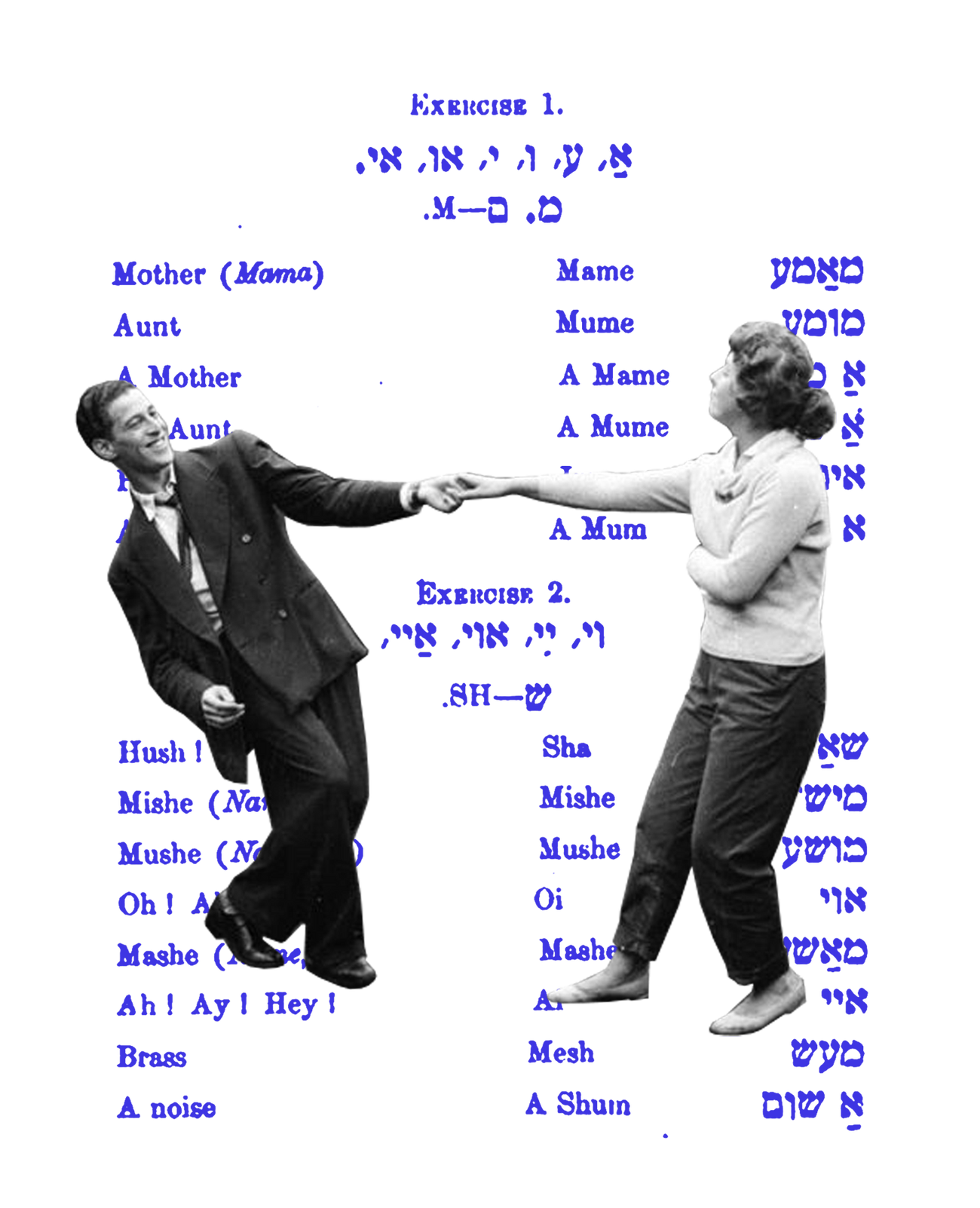

But pamelech, pamelech (slowly, slowly), I started to learn. I learned the peculiar way Yiddish is written with Hebrew letters but not Hebrew spelling rules. I learned the three grammatical genders, how to conjugate compound verbs and inflect nouns. I learned the nominative, accusative, and impossibly illogical dative case.

I also learned that Yiddish idiomatic expressions were deeply rooted in Jewish culture, with allusions pointing clearly back to Jewish tradition. It’s not a silk purse that you can’t make out of a sow’s ear—it’s a shtreimel (the black hat worn by the ultra-Orthodox) you can’t make out of a pig’s tail. When someone cries crocodile tears, in mameloshn they’re shedding “Joseph’s brothers’ tears.” Yiddish, I started to understand, was a language that looks at the world through Jewish-colored glasses.

One night, hunched over my homework, I wrote my first grammatically correct Yiddish sentence: “Mameh, tantztu mit’n tat’n?” (“Mom, are you dancing with Dad?”) My late parents loved to dance, so it felt perfect. I wrote the sentence on an index card and propped it up on the bookshelf. Inexplicably, I found myself getting choked up. Real tears, not Joseph’s brothers’ tears.

I started drawing a smiley face in my notebook next to every word that I recognized from childhood: Shisl, boich, grizhn. Bowl, stomach, to gnaw at. Random words without deep emotional meaning, per se.

But now that my mother and father were both gone, these old/new words were conjuring up emotional rustlings, like fallen leaves blown about in the wind. Every day more words emerged from the shadows, half-remembered memories in black and white, now in vivid color.

By the end of the course, my notebook was full of smiley faces, and I thought that maybe, just maybe, I was beginning to hear the voice of the previously silent language.

I returned home to Miami and searched for a local teacher to continue my studies. I found one who had multiple degrees and decades of experience teaching in the Jewish community. Like me, she was a language lover. We spent hours debating why a certain sentence had a verb inversion or an implied preposition, which required the diabolical dative case.

I continued to fill my notebook—now on Volume 2—with Yiddish words and expressions. And many, many smiley faces.

One day, as I was clumsily trying to describe the new home I was about to purchase, I asked my teacher, “Vi zogt men (How does one say) ‘closing costs’?” She stared at me ruefully and said, “Vi zogt men? How does one say? One doesn’t say! One did not say it back then because there was no such thing as ‘closing costs’ in Eastern Europe before the war, and one doesn’t say it now because no one speaks Yiddish anymore, except for the ultra-Orthodox! So one doesn’t say!”

I was stunned but knew she was right. And I suddenly understood that for all the hundreds of students taking summer Yiddish courses, for all my hours of homework, for all my joyful proclamations on Facebook of “Yiddish lebt!” (Yiddish lives!), there is still no country where Yiddish is the official language and virtually no children being born with Yiddish as their actual mameloshn, outside of the insular ultra-Orthodox community.

I went home after class that night and thought, “What am I doing? Why am I spending all this time and money learning a language where one simply ‘doesn’t say’?”

I kicked myself for not having studied the language while my mother was still alive. “Now that I can actually speak to her in Yiddish,” I thought, “I can only do so when I stand before her and my father’s graves.”

And then, a few weeks later, I came across a few unpacked cartons in my extra bedroom with things I hadn’t thought about or touched in years. When I reached the last carton, I stuck my hand inside. I felt something, palm-sized and made of hard plastic. I knew what it was even before I saw it.

It was the black mini-cassette recorder I had taken to Latvia in 2002.

I hesitated for a moment. Would the tape still work after 17 years? What if I’d erased it with a shopping list or a lesson plan or an idea for an article?

I found two new AA batteries and inserted them into the back of the recorder. I pressed “play.” Two minutes of white noise. My heart sank.

And then I realized that all the tape was collected at one end of the cassette. I pressed “rewind” and watched the tiny wheels spin as the tape moved from right to left.

When it reached the beginning, I pressed “play” again and held my breath.

I heard “Ich bin dayn kouzineh Phyllis Weinstock. Ich hob a man un tsvey zin.”

My mother, already dead for years. The only recording I have of her voice in Yiddish.

Or in any language.

I’m in my eighth year of Yiddish classes now, and sometimes I still think that maybe my studying the language is an exercise in futility. Maybe there is no country where all the little children go to school in Yiddish and TV is broadcast in Yiddish and everyone laughs and fights and makes love in Yiddish. Maybe learning Yiddish is shouting into the void.

But sometimes the void answers back. And it answers back in Yiddish.

Jeffrey Weinstock lives in Miami and teaches at the University of Miami.