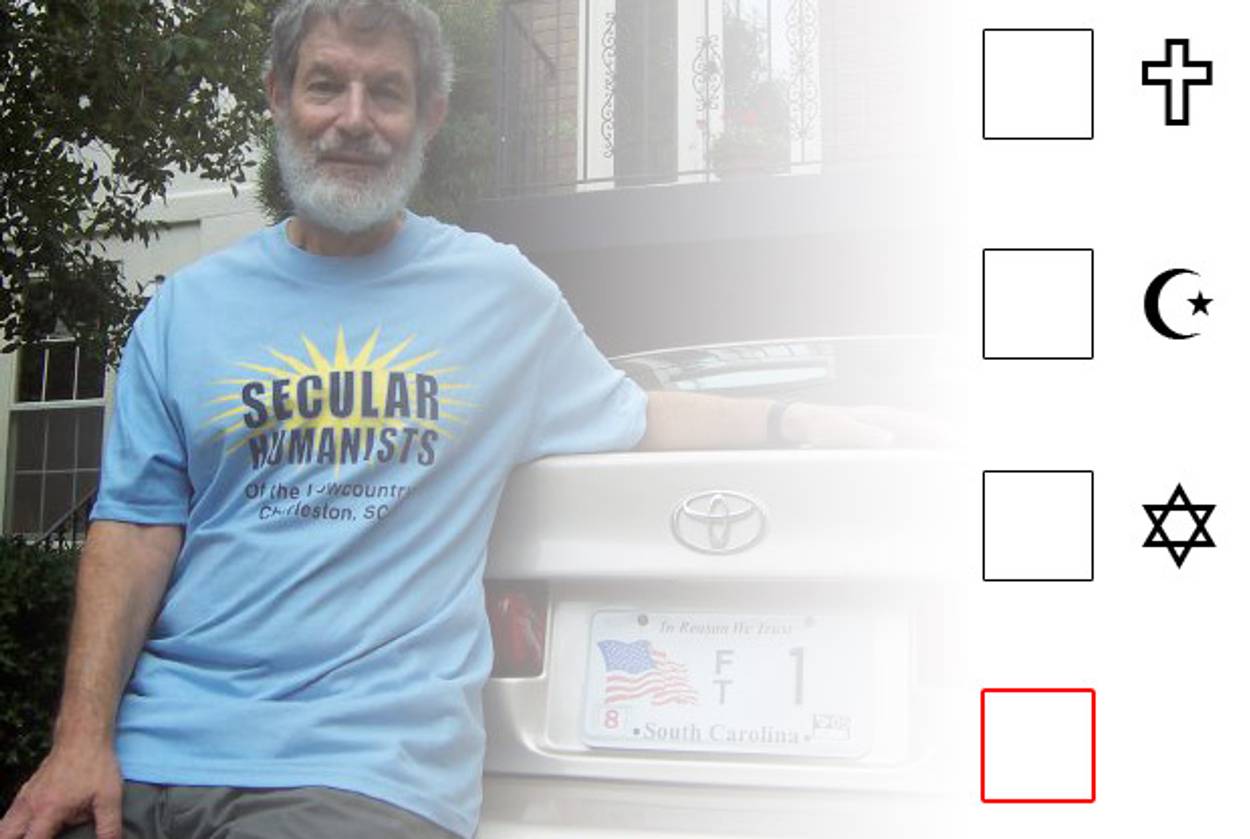

South Carolina’s Secular Crusader

In a new memoir, Herb Silverman recounts his legal battle against a state ban on atheists seeking public office

The 2012 presidential race has brought religion into politics on an explicit level, as the candidates have competed to establish their bona fides as believers and defend their religious affiliations. And who could forget former Republican candidate Rick Santorum’s statement that the very concept of separation of church and state made him want to throw up? This year’s presidential contenders’ religious practices rest squarely at the center of political discussions.

Herb Silverman, founder and president of the Secular Coalition for America, has been following all of this very closely. During the Republican primaries, particularly around January’s race in his home state of South Carolina, Silverman wrote a series of columns for the Huffington Post in which he humorously observed the efforts of various politicians to impress voters with their spiritual credentials. (Full disclosure: I was his contact when he submitted his columns.)

Silverman has spent much of his life thinking about his beliefs, in an iconoclastic manner evidenced in his regular “On Faith” columns in the Washington Post. More significantly, Silverman knows about the intersection between religion and politics first-hand. As he recounts in his new memoir, Candidate Without a Prayer: An Autobiography of a Jewish Atheist in the Bible Belt, Silverman—raised as an Orthodox Jew and now an outspoken atheist—ran for office in South Carolina to challenge a state law requiring candidates to assert religious faith. After an eight-year battle, Silverman won his legal challenge.

Using his own experience and years of political observation, Silverman uses his book to expose the hypocrisy and the lack of logic in politics and public life. Writing in simple prose that brings to mind the clarity and depth of a mathematical theorem, he traces the youthful origins of his atheism and his journey to its “logical” conclusion: activism on behalf of secular America.

“I’m hoping for the day when we will judge candidates on their positions and integrity,” he writes, “and not on their professed religious beliefs.”

***

Born to working-class parents in Philadelphia in 1942, Silverman formed his identity in response to a world where religiosity was the status quo. Hypersensitivity to hypocrisy manifested early in his development. The built-in equivocations of Jewish rules and rituals led to his decision to “follow only those [rules] that made sense,” he writes in his memoir. This reliance on logic bloomed into an affinity with mathematics.

Intuiting that God and infinity were related concepts, he spent much of his early adolescence trying to calibrate the two through study and reflection. “The most important lesson I learned was that infinity is a theoretical construct created by humans, and that the number ‘infinity’ does not exist in reality,” he writes. “If finite man created infinity, perhaps finite man created God and gave him infinite attributes. Infinity is a useful concept to help solve math problems. Was God merely a useful concept to help solve human problems?”

Recounting his youth in lucid and often humorous terms, Silverman recalls that even as he studied for his bar mitzvah, he was coming to the realization of his disbelief. And by the time he completed that rite of passage, he could not avoid his own reasoning. “In Talmudic speak, you might say that God led me to mathematics and turned me into an atheist,” he writes.

Mathematics became his passion and his profession. And when a tenure-track teaching position opened in 1976 at the College of Charleston, in South Carolina, he moved below the Mason-Dixon Line, he recounts, to a place where some gracious people still referred to the Civil War as “The Late Unpleasantness.”

Despite the success of his honest self-presentation as a Jewish/Yankee/atheist, Silverman’s trajectory was set for inevitable confrontations. It took someone of his ilk to point out, for example, that the college failed to honor the separation of church and state when it held “Spiritual Enrichment Days” in which all the activities represented a Christian fundamentalist perspective.

His clear-headed advocacy of progressive causes provoked the expected backlash. While he won many friends and sympathizers, notes calling him the antichrist were also pinned to his office door. But these struggles proved to be merely warm-ups and only strengthened Silverman’s skill at responding to fundamentalists.

In 1989, Silverman learned that the South Carolina Constitution prohibited anyone who “denied the existence of the Supreme Being” from running for public office. Silverman had to pick up the gauntlet. It was in his nature. He was 47, unmarried, and relatively content, yet he recognized that this was the epiphanic moment when he knew what he should do with the rest of his life.

“I think it’s up to human beings to find their own purpose,” he told me in a recent phone interview. “And my purpose was to educate people about a secular world view.”

This is where Candidate Without a Prayer really catches fire, as he vividly describes his strategy to challenge South Carolina law by running for governor in 1990. He would have to run a campaign to establish that he was a legitimate candidate, in order to file any lawsuit, so he won the endorsement of the United Citizens Party, a black-led civil-rights group formed in the 1960s. But the South Carolina Election Commission, according to Silverman, directly undermined the endorsement, and he would eventually run as a write-in candidate. Campaigning even as his suit made its way through the court calendar, Silverman delighted in the opportunities to publicly articulate his views. (It was through an article in the Philadelphia Inquirer that his mother found out what he was up to—“not the best way to find out that her only child was a gubernatorial candidate, and an atheist,” he confesses.) But just days before the election, the presiding U.S. District Court judge dismissed the case on the grounds that it would be premature to rule on the merits of the case unless he won the election. “To the surprise of no one,” Silverman writes, “I lost.”

Not to be dissuaded from a struggle now lodged in his ethical core, he applied the following year for a state license as notary public. Silverman reasoned that if South Carolina were to grant him the license, “it would be an admission from the state that religious tests could no longer be a qualification for public office.” Naturally, he crossed out the oath on the application that said “so help me God.”

“My point,” Silverman writes, “was that it’s proper for government to regulate some behavior, but it’s neither proper nor possible to regulate belief.”

Silverman’s account of the resultant back-and-forth between his petition for a mundane license and the refusal of Gov. Campbell—his former opponent in the gubernatorial race—to approve it is the stuff of high surrealism. A deposition established that 33,471 notary applications had been approved by the state of South Carolina between 1991 and 1993. “To my knowledge,” Silverman writes, “I am the only person in the history of South Carolina to be rejected as a notary public.”

After an eight-year battle, on May 27, 1997, the State Supreme Court unanimously affirmed the circuit court’s prior ruling that the religious test was unconstitutional with reference to U.S. law. Silverman hilariously describes his jubilation at picking up his notary commission from the county clerk’s office.

Silverman went on to found the Secular Coalition for America, among other groups, to advocate nationally for greater tolerance and understanding of the non-religious constituency. While he shares his views with a minority of compatriots—16 percent of Americans declared no religious affiliation and less than 2 percent described themselves as atheists in a 2010 Gallup poll—he is clear about the importance of maintaining church-state separation and bothered by the tendency of atheists to keep their views in the closet.

“A worrying trend for me now is how politicized the Christian fundamentalist sector has become,” he told me this month just before setting off to the American Humanist Association convention in New Orleans, “running political campaigns and putting money behind them. This makes it ever more important for the secular humanist movement to communicate what they’re about.”

Some five months before the 2012 elections, American voters are already weary of the hypocritical exploitation of religion by the political class. Silverman’s brave and illuminating book may serve to open some of those closets and to prevent some of the doors of religious intolerance from being slammed in the faces of those who emerge.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Laura Paull is a journalist in the San Francisco Bay Area who followed the primary races in 2011 and 2012 as the former supervising editor for Citizen Journalism at the Huffington Post.

Laura Paull is a journalist in the San Francisco Bay Area who followed the primary races in 2011 and 2012 as the former supervising editor for Citizen Journalism at the Huffington Post.