Windows Without a Home

When synagogues close or congregations merge, what happens to the stained-glass windows that once graced their sanctuaries?

In 1974, Chaim Gross’ massive stained-glass work “Rebirth” was installed in Temple Emanu-El’s sanctuary in Engelwood, New Jersey. Situated behind the ark, at 19 feet across and 6 feet high, it spanned the length of the pulpit. Twenty-six years later, when this Conservative congregation left its building for a new one (just a few miles north in Closter), congregants brought the artwork along with them, and although the work didn’t suit the new sanctuary, they found an eye-catching spot for it in their reception hall (now a popular backdrop for wedding photos). Synagogue vice president Robert Heidenberg, reflecting on the serious undertaking of removing the 4,000-piece window and reinstalling it, explained, “We wanted to retain our heritage.”

Stained-glass windows often exert a powerful emotional pull on synagogue communities. More than a two-dimensional painting or even a three-dimensional sculpture, these works occupy a fourth dimension, transmitting and refracting light, filling the volume of sacred space with a mystical—some even say magical—quality. The desire to keep these colorful windows— often referred to as the “soul” of the congregation—during a move is strong, even when it calls for great expense and design ingenuity.

Unfortunately, not all synagogues have been able to do what Temple Emanu-El did. As increasing numbers of American synagogues shrink, merge, and disband, the colorful windows that captivate worshippers, shaping the atmosphere in their buildings, often find themselves without a home—ending up in basements, or storage units, if they aren’t simply left behind. Stained glass may become yet another casualty of American congregational decline.

Art historian and preservationist Samuel Gruber cites 1845 as the first recorded use of stained glass in American synagogues, when the Baltimore Hebrew Congregation is described as having one installed over its ark. Early on, synagogue window design consisted primarily of geometric or decorative patterns with occasional Jewish features such as the six-pointed star or Ten Commandments tablets. With the synagogue building boom that followed in the decades after WWII, large sanctuaries and gala entertainment halls invited new trends in windows.

Stained-glass artists emerged who dedicated themselves to developing specifically Jewish themes focusing on the holidays, the days of creation, the Twelve Tribes, and encounters with the Divine, as well as profound ethical ideals such as justice, liberty, and peace. Other artists—like Chaim Gross—did not generally work in glass, but collaborated with artisans to convert their creative vision onto windows.

For over four decades, Mark Liebowitz has been among the handful of U.S. master craftsmen who have devoted much of their careers to synagogue art. Today he and his artist wife, who share Nancy Katz/Wilmark Studios, work together in a converted mill space in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. Since starting his business in 1979, Liebowitz has worked with dozens of artists to create stained-glass windows in over 300 locations, among them more than 50 synagogues. “I would go to the conventions of the different [Jewish] movements,” he reminisced. “There’d be four or five of us [stained-glass people] there every year. We all knew each other. We watched each other’s kids grow up. There was work for all of us then. You could raise a family on that work.”

But as membership in synagogues and churches has declined and congregations contract, Liebowitz’s commissions have been coming in with less frequency. Now he is accustomed to receiving calls from congregations where he worked decades ago. Back then, he made and installed their new windows. These days, they are asking to have them removed. In the case of a synagogue merging, Liebowitz might reconfigure and retrofit them into their new locale. Often, though, the windows are simply taken out and put into storage, too dear to discard, but without any clear prospects for a new home.

That is what has happened with the glass panes that once served as a focal point of Milwaukee’s first Conservative synagogue, Beth El Ner Tamid. The windows were designed by stained-glass artist Helen Carew Hickman, and dedicated in 1963 when over 1,000 families belonged to the synagogue. In 1984, while still vibrant, the congregation moved into a new building, with plans intentionally drawn to accommodate their windows. They were mounted on both sides of the Torah ark, casting a dramatic light across the sanctuary.

By 2012, with an aging and dwindling membership, BENT merged with the larger Beth Israel, also a Conservative synagogue, and moved into Beth Israel’s building. BENT’s windows were brought along in the merger, but with no obvious place to display them, they went into the basement.

I saw them while touring the building during a 2017 visit. Mixed up with a hodgepodge of sacred items in a storage closet, they lie stacked on top of each other in a skeletonlike pile of darkened plates. “Perhaps we’ll mount them in a hallway one day,” former synagogue president Howard Loeb suggested. But three years have passed since then, and they still remain in the basement, without a clear plan for installation.

At least the building has space to store them. Not all synagogues do.

At 8 feet tall, the windows that belonged to B’nai Israel in Saginaw, Michigan, are so large that when they were removed from their building in 2005, they had to be put in an off-site storage unit, where they’ve been ever since.

These brightly colored stained-glass panels were commissioned by B’nai Israel members Dave and Florence Ruskin in the 1960s, and fabricated in Paris by French craftsman Jean Barillet. At the time, this Conservative synagogue was in its heyday, numbering some 250 families. But with industrialization, the city saw a steep population decline from nearly 100,000 in the 1960s, to fewer than 52,000 by 2010.

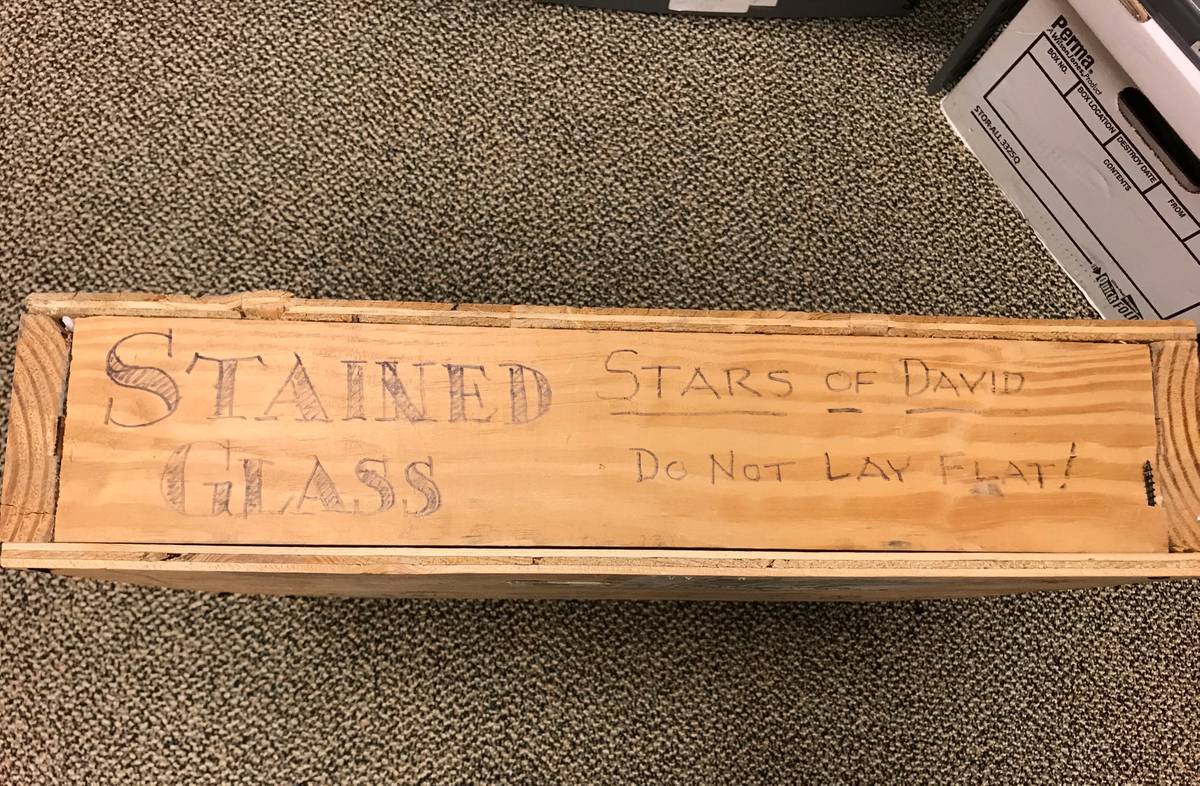

Jews were among those who moved out, so that by 2005 B’nai Israel could no longer sustain itself, and joined with Temple Israel, about 15 miles north in Bay City. The stained-glass windows were removed from the building before it was sold. With no place for them in the Bay City synagogue building, they were crated up and taken off-site.

Now, 15 years later, the need to get their storage fees off the books has motivated a few congregants to step up their efforts to find the windows a new home.

Stanley Meretsky, who is spearheading the project, has a family connection to the windows. He married in B’nai Israel shortly after they were installed, and the Ruskins—who commissioned them—were his wife’s parents. In addition to this personal tie, Meretsky views the windows as one of the few tangible remnants of the Jews’ history in the region, which stretches back nearly 150 years. “My goal?” Meretsky explained. “That these wind up someplace in Michigan, that they stay together as a group, and that they go to a Jewish organization. I want to find them a good home.”

Meretsky has gotten the word out through the press that they are available cost-free. In the meantime, their images of the Israelite tribes remain tucked away in the dark.

Synagogues across the country are in similar situations.

B’nai Sholom in Quincy, Illinois, deconsecrated its 150-year-old building last year. Still without a buyer, congregants do not know how much longer the building will remain standing, and worry what will happen to its simple, but elegant windows—in particular, the large circular one, an estimated 8 feet in diameter, centered above the front doors, that spells out the congregation’s name.

Beth-El in Fort Worth, Texas, has 24 stained-glass medallions in storage, some measuring a foot in diameter and others 18 inches. Designed in 1946 by modernist Erno Fabry, they were excised from the congregation’s previous building. Synagogue historian and archivist Hollace Weiner hopes to have them reconfigured and mounted. But at the moment, they remain in boxes, where they’ve been since the congregation moved into their current home in 2000.

And Ahavath Israel in Kingston, New York, dissolved in 2018, and has yet to find recipients for its 2-foot by 4-foot windows. Their playful abstract images of the Jewish holidays and the days of creation were designed by Robert Pinart (1927-2017), renowned as one of the greatest glass artists of his time.

What will eventually happen to these various pieces, and others like them is unclear. Some may remain in the buildings where they are, passing into the hands of new owners—church congregations, or apartment residents—who honor them. Some may be removed, picked over by opportunists, and put up for sale. While others might simply meet the fate of any used-up material, broken and left to waste.

A fortunate few, like Chaim Gross’ “Rebirth,” may be given homes in new buildings. But with Jewish congregations closing up faster than new ones are opening, this scenario is becoming increasingly less likely. Meanwhile, Samuel Gruber notes with some urgency the need to “get out there and document” these works of art before it’s too late.

Alanna Cooper serves as the Abba Hillel Silver Chair in Jewish Studies at Case Western Reserve University. She is the author of Bukharan Jews and the Dynamics of Global Judaism.