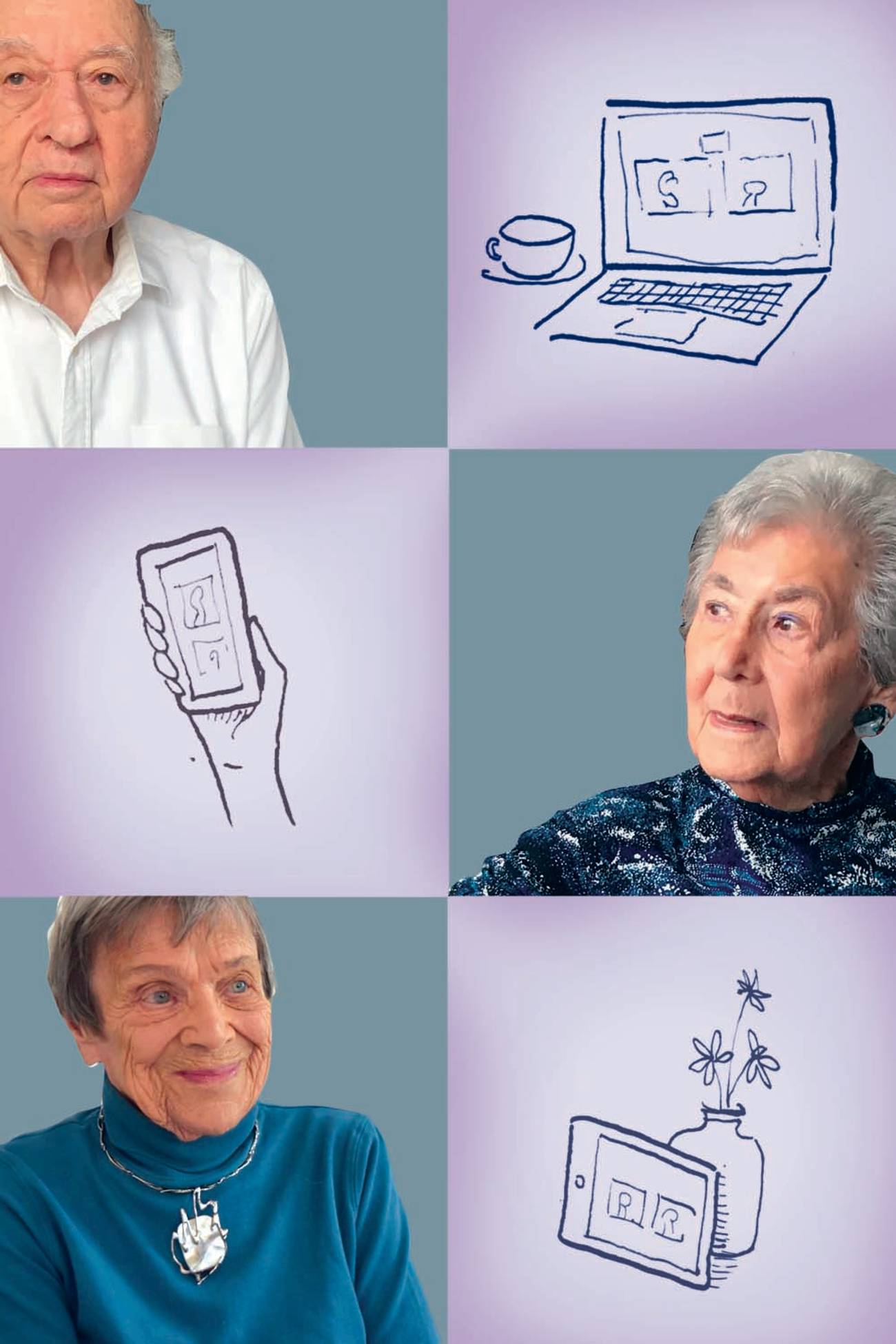

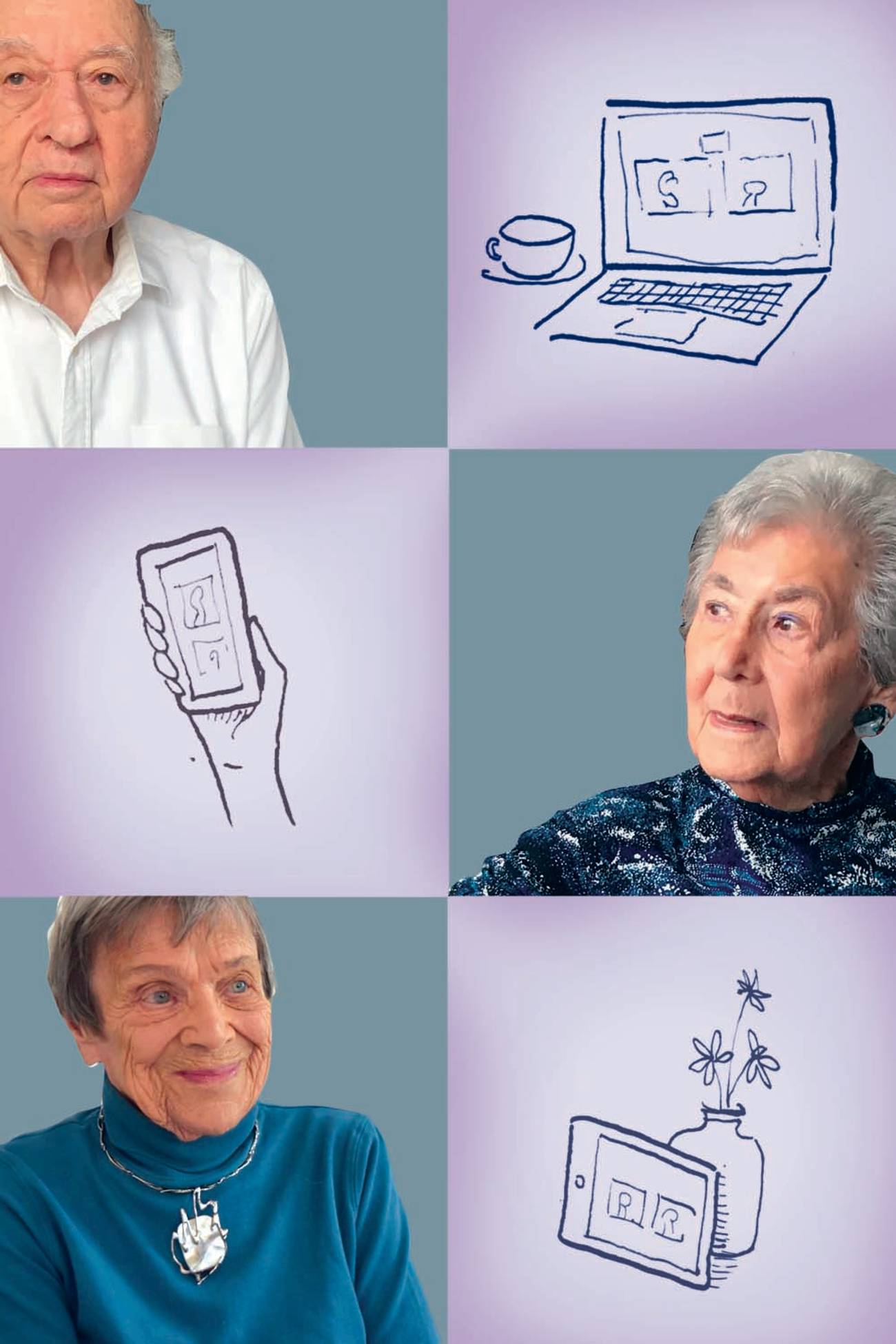

Holocaust Survivors Continue Gathering—Online

A German-speaking group in New York has been meeting weekly since 1943. Even the COVID-19 pandemic couldn’t stop them.

Since 1943, German and Austrian Holocaust survivors have gathered in New York City for what is known as the Stammtisch. Every Wednesday, its members meet to speak German and share a meal, discuss political and cultural developments, and maintain a connection to their pasts, despite the trauma and loss they experienced.

“They are like a family to me,” said Marion, 96 and originally from Berlin. “I can’t imagine a life without the Stammtisch.”

“It is a piece of home, a connection to Austria,” explained Arnold, 96 and grandson of the Austrian composer Arnold Schönberg. “Being able to talk in my mother tongue, that’s why I am there. We only talk German. We are all refugees.”

Apart from a short summer break last year, the Stammtisch has never been paused. When the COVID-19 pandemic began, it seemed impossible for the gathering to continue, but it has—online. In March, the Stammtisch moved to Zoom.

“Stammtisch” is defined by dictionaries as a table, typically in a restaurant, which is reserved for the same group of people at the same time every week. This particular New York City Stammtisch was founded in 1943 by a Bavarian writer, Oskar Maria Graf, and a Viennese merchant, George Harry Asher. In the 1940s and ’50s, the refugees met in restaurants and émigré cafes, together enjoying meals of meat, which was strictly rationed at the time. Later, they continued to meet in private apartments. German and Austrian artists and writers in exile discussed their works at the Stammtisch, reciting poems or reading short stories, in line with the tradition of Viennese coffeehouses. As the decades passed, politics moved increasingly to the center of the conversation.

Eating and drinking together was at the center of the evenings. Everyone contributed something. “I used to make fresh palatschinken [Austrian crepes], filled with apricot jam, once a month,” said Arnold proudly. Austrian specialties were the highlight, such as homemade traditional Viennese potato salad, also prepared by Arnold, or apple strudel. Participants would talk about their favorite foods, Wiener schnitzel and Sacher torte, or Austrian and German whole wheat bread.

WWII and Holocaust refugees were joined by German-speaking friends of all generations and walks of life. Some evenings, 96-year-olds were entranced in conversations with 18-year-olds, most current or former “Gedenkdiener,” young Austrians and Germans completing a service year at Holocaust museums after graduating from high school. Up to 20 people squeezed around a narrow table, local New Yorkers joined by visitors from Vienna or Berlin.

Trudy, 94 and born in Vienna, hosted the Stammtisch in her apartment on the Upper East Side. She wanted the gathering to be understood as cultural, not religious. Only about half of the participants are Jewish. “It’s a bit exhausting,” Trudy said of her role as a hostess, but she said it with a laugh. Baking cakes, tidying everything up—she wanted to make sure everything was “beautiful,” something she got from her mother, who was also an artist. “The weekly meetings give my life a structure.”

As the participants aged and Trudy started getting tired earlier, the start time of the Stammtisch gradually shifted, from 8 p.m. to 6:30. But the conversation remained a mix of easygoing chatter and serious discussion, including about politics both in the old and new worlds. They discussed holiday traditions, Jewish and non-Jewish, recounted travel experiences to countries of origin, and shared childhood memories, the good and the traumatic ones.

Trudy, whose original name was Trude, comes from a nonreligious Viennese banker family and emigrated from Vienna to New York in 1939, after her grandfather had been interned in Dachau for months. “We were very lucky,” said Trudy, especially because a distant relative in New York had given them affidavits without hesitation. As a result, her closest family escaped the Nazi terror unscathed. At the age of 13, shortly after her arrival in New York City, Trudy was sent to a public elementary school on the Upper West Side, with much younger children. Trudy barely spoke English at the time. She still vividly recalls sitting alone and desperate on the steps in the school’s hallway, crying, when a girl from Puerto Rico, who could not speak a word of English herself, sat down next to her. The girl stretched out her hand; Trudy took it. Together, they mastered their first days in a foreign and incomprehensible environment. “I was such a shy child,” said Trudy. “With her, I was not alone anymore”.

Exuding Viennese charm, Arnold proudly mimics the voice of his famous grandfather Arnold Schönberg and wrote a book about him. He speaks five languages fluently and eagerly discusses his mother’s recipe for Viennese potato salad. Arnold emigrated from Vienna to New York with his family in 1938. The anti-Semitism he confronted in Vienna was disturbing although he was only partly Jewish. “That was enough at the time,” he said. His grandfather, already in California, helped to obtain the necessary documents for the escape to New York. After finishing his studies, Arnold enlisted in the U.S. Army. During the recruitment interview, he was asked if he would shoot the enemy, his former compatriots. Arnold replied: “This depends. If I noticed it was a school friend or an uncle, I’d probably not shoot or miss.” Fortunately, he never faced such a situation; he was deployed on the front line as a paramedic for wounded soldiers and later as a translator at a military hospital in Naples.

Marion is an elegant woman, who always wears a silk scarf and earrings. Proudly, she still drives her car, enjoying the independence. She escaped from Berlin in May 1939, at the age of 16. She boarded a Kindertransport, a rescue operation for mostly Jewish children prior to the start of WWII, to Great Britain: “The conditions at the departure station in Berlin were catastrophic. The children cried; the parents cried. The young children did not understand what was happening to them at all. I was 16 years old and I understood that my parents would do everything they could to get out.” On the train, Marion met a girl with whom she had attended high school. “I was glad to have found a travel companion.” Marion ended up living with relatives in London and after the war was reunited with her parents, who had survived Theresienstadt. For decades, she helped Holocaust survivors seek reparations and social security benefits. “It is a great satisfaction to me that I was able to help so many people,” she said.

Marion frequently reflects on the concept of Heimat, a German word for home, a place of belonging. “Many Viennese Jews have a deep longing for the old Vienna. I don’t have a longing for Berlin, but a feeling of nostalgia when I am there. Those people who are sipping their coffee, know where they belong. I lost that. As much as I love New York, I still feel uprooted. My Heimat has been stolen from me by Hitler.” The Stammtisch filled this vacuum in her life to some extent. She now counts many Germans among her friends, something she would not have thought possible earlier in her life.

The coronavirus outbreak has pushed the Stammtisch to the virtual space of Zoom since March, changing a few long-standing habits. The starting time was moved to 4 p.m., to accommodate different time zones: The Gedenkdiener were forced to cut their terms of duty short this year and returned to Europe earlier than anticipated, dialing in from overseas. Others were caught off guard traveling in Europe, finding themselves unable to return due to restrictions. Now, with an earlier start time, those in Europe can easily join and old friends connect via screens. Typically, between six and 12 join the conversation, lively and interesting as always. Only the sharing of meals will have to wait until the pandemic is over.

Marion, quite computer savvy, manages to connect via the online platform. Trudy participates by telephone. The group sang a song for Arnold’s 96th birthday in March, the melody a bit off due to technical delays. Laughing, everybody happily continued to sing, finishing the song jointly.

Many things have not changed. German is still the language of conversation and both Viennese and northern German accents can be heard, quite distinct and easily distinguishable. The informal German du, similar to the Spanish tú, and first names are being used.

Conversations these days focus on the different stages of the outbreak and health. Arnold suffered from a cold and a cough a while back, worrying all. One recent visitor to the Stammtisch died of COVID-19 back in Vienna. Those demonstrating in the wake of George Floyd’s murder get tested repeatedly. Infection curves and measures taken by governments, including in the U.S., Austria, or Germany, and the social impact of the crisis are examined. “I am very concerned about the reports about children suffering from hunger in this country,” said Marion. And: “If I were younger, I would join the demonstrations.” Funnily, the conversation circles repeatedly around hairstyles and either the need for haircuts or color treatments, or both. “My hair is getting longer and longer,” Marion added. This seems to be a topic of similar concern for young and old.

The core members of the Stammtisch have been through much worse than a viral outbreak. Marion and Arnold look forward to joining Trudy again in her apartment as soon as it is safe and to continuing this cherished tradition that has existed for more than three quarters of a century. Trudy is hopeful: “I miss everybody,” she said. “But this will pass. We will meet up again and resume our weekly meetings in person.”

Stella Schuhmacher is a New York City-based writer who is originally from Austria. She publishes a regular blog, New Yorker Stories, in the Austrian newspaper Der Standard.