Teaching Kids About the Plight of Refugees

A new crop of books introduces young readers to people who fled their homes—in earlier decades, and today

It hasn’t even been a year since I did a roundup of children’s books about refugees. But the problem certainly hasn’t gone away—and there’s already a whole new crop of superlative books out there.

Let’s start with picture books for the youngest kids. Lost and Found Cat: The True Story of Kunkush’s Incredible Journey by Doug Kuntz and Amy Shrodes, illustrated by Sue Cornelison, is that rare thing: a picture book about an important issue that is neither didactic nor boring. It’s the true story of a beloved kitty named Kunkush, smuggled out of Mosul, Iraq, by his fleeing family; in the crush of refugees splashing ashore on the island of Lesbos, Kunkush escaped from his carrier and got lost. Volunteers found the cat, who was being bullied by a local feral cat colony, and began a worldwide search on social media for his family. Ultimately, in the glow of a zillion news cameras, the family and their adored pet were reunited.

Lost and Found Cat’s prose is workmanlike, but the subject matter (CUTE CAT REUNION! COME ON!) and warm, bright, soft, jewel-toned illustrations sell it, big-time. Cornelison renders the ultra-fluffy, white, expressive Kunkush with a ton of personality—I especially love the pictures of him in an undignified sweater vest. The story’s a great way to talk with kids about why people have to flee their homelands, why volunteering can be such a fulfilling mitzvah, and how adorable animals can serve to draw attention to uncomfortable issues people often want to turn away from. I do wish someone had fact-checked the Arabic—when the family’s mom, Sura, sees Kunkush, she exclaims, “Ma habibi!” The text explains helpfully, “That’s Arabic for ‘my darling.’” Yeah, no, it isn’t. In Arabic, as in Hebrew, “ma” means “what.” Habibi, with no extra words needed, means “my darling”—it’s already a possessive. Ugh. But on the upside, I was grateful that the afterword by the authors mentioned an distressing truth most children’s books would avoid: Kunkush died only three months after being reunited with his family. This messes up the happy narrative, but it opens up more discussion fodder for families about whether expensive rescue efforts for beloved animals are always worth it, and why or why not. (And since the fact is only mentioned in the afterword, you can ignore it if you wish.) I wanted to be annoyed that the authors are selling “Kunkushie” stuffed plushies, but learned that the toys are being created by The Amal Project, a sewing initiative by refugee women, and that funds raised will help sponsor salaries for teachers for refugee kids in Izmir. Fine. Works for me. (Plus the stuffed Kunkush is super-winsome.)

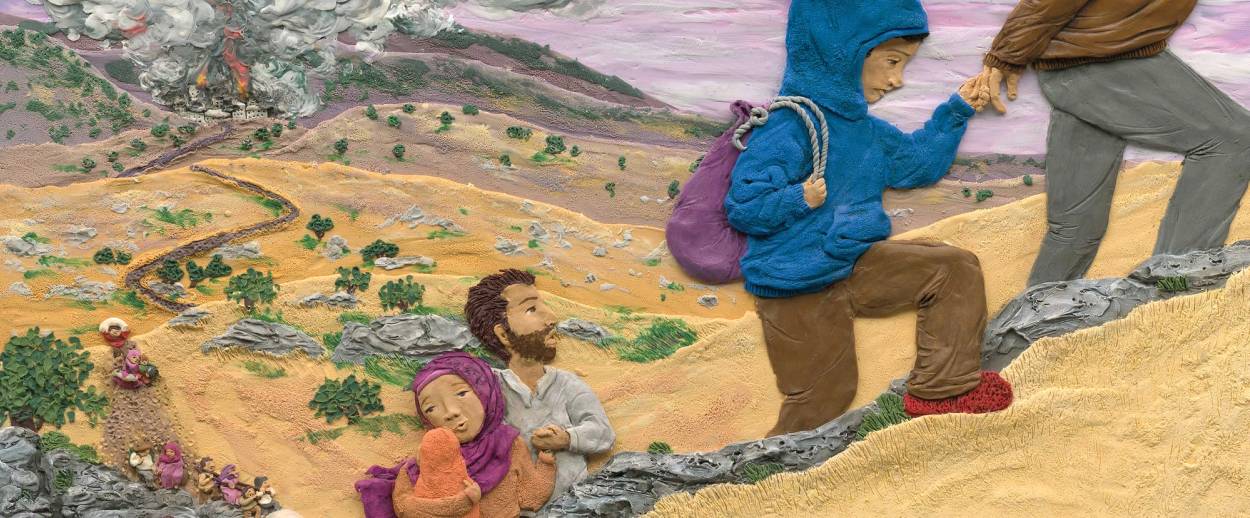

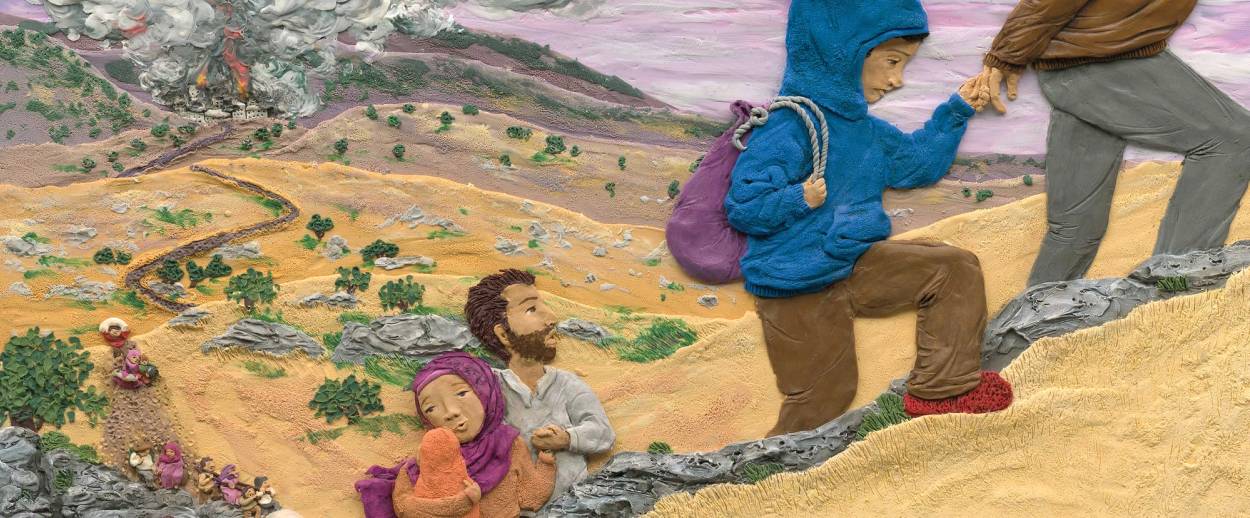

My Beautiful Birds by Suzanne Del Rizzo is another pet-centered, refugee-focused picture book with terrific art—I’ve never seen anything like it. Del Rizzo uses polymer clay, Plasticine, and paint to create 3-D sculptures so textured you want to reach right into the paper to touch them. Each page took her as many as 40 hours to complete, and it shows: This is luscious, breathtaking fine art. Again, the writing isn’t as good as the images. Del Rizzo wrote the book in an attempt to explain the refugee crisis to her own kids, and—understandably—she perhaps erred on the side of wishful fantasy. The (fictional) story introduces us to a little boy named Sami who has to leave his pet pigeons behind when his family flees civil war in Syria. He winds up in a tent city, unable to play soccer or paint, too sorrowful about what he’s lost. But one day a canary, a dove, and a rose finch fly into the camp, and Sami befriends them. “On bad days they know just what to say—Chitter, chitter, cooo, cooo—and what to do—nuzzle, nibble, cuddle … and when it is best just to be.” He begins to heal. One day, Sami spots a newly arrived, shell-shocked little girl and introduces her to the birds; the children smile at each other and the birds, and we know they’ll be able to move on. Alas, overly literal me wonders about the mix of reality-grounded refugee-camp horror with a lovely fancy about three different birds showing up at the same time and landing on a little boy’s outstretched arms … but parents can talk about poetic license with even little children. And again: Oh, that art.

Stormy Seas: Stories of Young Boat Refugees, by Mary Beth Leatherdale and Eleanor Shakespeare, is a picture book for older kids—I’d say 9 and up. It introduces us to five real refugees from different periods in history: Ruth, 18, who sets off from Breslau in 1939 to escape Nazism on the Saint Louis; Phu, 14, who flees Saigon in 1979; José, 13, who sets out from Cuba in 1980; Najeeba, 11, whose family escapes from Afghanistan in 2000 and seeks asylum in Australia; and Mohamed, 13, an orphan who runs from human traffickers in Ivory Coast in 2016. It’s the most “school”-ish of all the books here (it would be appropriate for research projects and classroom libraries) but it’s still really readable. And again, the design will help pull kids in: This time it’s snazzy mixed-media collage—faces in portholes, a hand on a globe, scribbles on school writing paper, a little girl standing in a giant flower—along with easy-to-absorb sidebars, definitions, and info boxes, and big pull-quotes in a cool, modern font. The fact that all these real-life boat journeys ended well is reassuring (we learn what happened to each character after they found safety), but the book doesn’t elide the truth or pull punches. The writing is compelling, with quotes from the kids: “I am not particularly interested in going to America,” Ruth notes, “I am interested in staying alive.” “We are at risk of drowning on the Pacific, but we prefer that risk to that of a brutal killing at the hands of the Taliban,” Najeeba says. The timeline of boat-refugee stories early in the text starts oddly late (yeah, yeah, Huguenots fleeing France in 1670, talk to me about Jews expelled from Spain in 1492) but this is a near-perfect overview of five very different places and time periods. It’s quite an achievement.

Seeking Refuge: A Graphic Novel by Irene N. Watts, illustrations by Kathryn E. Shoemaker is an odd duck. Watts has mined her own history for many years—at age 7, in 1938, she was on the second Kindertransport—and this graphic novel is a reworking of one of her earlier autobiographical novels. It’s stronger on story than facts—anyone looking for a history of the Kindertransport or specific countries, dates and numbers will need to supplement—but it’s a very good story. Marianne, 11, is sent out of Germany alone on the first Kindertransport. She winds up living with a snobby, rich Londoner, Vera Abercrombie-Jones, who’d wanted an older girl as a servant. Mrs. Abercrombie-Jones favors extravagant hats, so we know she’s crap. Her bitchiness is viciously, horribly enjoyable. (When Marianne has to borrow a tiny sum of money to replace her long-outgrown shoes at a rummage sale, Mrs. Abercrombie-Jones snaps, “You have shamed me in front of everyone! This once, I will overlook your behavior. What can one expect from a refugee?”) Mr. Abercrombie-Jones is clueless; when Marianne receives a cryptic postcard from her father, who has escaped to Prague, Mr. Abercrombie-Jones murmurs, “Beautiful city. Bridges, statues. Our glass decanter was made there.” Neither adult believes that Marianne’s father isn’t simply on vacation; when Marianne explains, “No, not holiday. He runs from Hitler, like me,” Mrs. Abercrombie-Jones tells her: “You exaggerate,” and sends her to her room. During the Blitz, when London’s children are evacuated, Marianne winds up in Wales. No one there wants to house a German Jew. She gets stuck in a home for unwed teen mothers, where she’s called a Christ-killer, and then in a creepy house with a woman mourning her dead daughter and intent on Marianne replacing her. (Dead Elisabeth’s oversized doll is spooky as hell.) In the end, Marianne’s mother finds her and they return to London.

I seem to be in the minority in liking the graphic novel’s art—it’s all graphite pencil, no color, minimalist and dark and a little blurry. To me, it’s fitting for the story, which is told entirely from Marianne’s point of view: She feels small and lost, and often looks that way in the frame. The only large, detailed face we see is Mutti’s, in Marianne’s memories, and she’s beautiful.

Finally, allow me to introduce a novel that is pure kid crack: Refugee by Alan Gratz. Even kids who don’t like to read are apt to devour it. The author’s Brooklyn Nine was on my best children’s books of the year list back in 2009; here again, it’s obvious that this dude does his history homework and then hides it in a total page-turner. (This is the beets in a brownie of kid lit.) There are explosions, sharks, gunshots, paranoia, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle merchandise, armed robberies, a cute kitten, tear-gas bombs, greased-doorknob pranks, a bar mitzvah, and a bad guy so bad he beheads a child’s stuffed animal. The story opens with a terrifying scene on Kristallnacht, then whipsaws in short, thrilling chapters among three characters’ attempted escapes from danger: Josef, a boy from Breslau on the Saint Louis in 1939; Isabel, a Cuban girl whose family is hungry and uncertain in Castro’s Cuba in 1994; and Mahmoud, a Syrian boy fleeing massacres and cluster bombs in Syria in 2015.

Each kid is more than an observer to history; they’re all brave and resourceful participants in their own story, not helpless victims. Isabel trades her beloved trumpet for gas to power the boat to Miami; Mahmoud leads a prison revolt; Josef steps up to become the man of his family after Dachau destroys his father’s mental health. A small part of me is appalled that Gratz turned horrifying historical events into three different jam-packed pulpy thrillers. Is this trivializing? I don’t know, but most of me is wildly impressed that Gratz wrote a book so exciting (every chapter ends on a cliffhanger) that kids of all sorts will actually read it, and learn a ton without realizing it. At one point, I gasped so loudly that the orthodontist’s assistant jumped up, snatched her hands out of my daughter’s mouth and took two steps toward the door. I’m telling you: page-turner. And the Syria story taught me a lot I didn’t know about how modern technology plays a role in refugees’ escapes. (I viscerally understood the importance of iPhone chargers in a way I never had before, and What’sApp, TripAdvisor, and texting all are vital to Mahmoud’s journey.) The very end of the book, where we figure out how all three stories intersect, is extremely satisfying, and Gratz provides a helpful afterword about what in the book is true and what’s creative license.

Look, I know there are an infinite number of crises to pay attention to right now. We can focus on only so much at once. But the refugee problem isn’t going away, and understanding the suffering of others—whether filtered through our own lived or epigenetic experiences or not—is essential to building a better world. Books about the refugee experience can help our children become more empathetic people, more active seekers of social justice, more fervent participants in tikkun olam. As Jewish parents and as the People of the Book, isn’t this what we want?

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.