Tevye vs. Tevye

I never liked ‘Fiddler on the Roof.’ But watching ‘Tevye’—a Yiddish film released 80 years ago, long before the musical—with my father, I changed my view of the legendary lead character.

I was 5 or 6 years old when my mother took me to see Fiddler on the Roof on Broadway in 1969. I still remember feeling sad at the end of the play. Tevye appeared on stage one last time with his broken-down wooden wagon, far behind everyone else—the last of the people of Anatevka. He had a loneliness that spoke directly to the loneliness of a little boy. What would happen to him?

Then, in 1971, when I was 8 years old, we went as a family to see the film version. I was a little older and I felt a different sadness. It was a deep-in-the-stomach, end-of-the-world sadness that lingered way past the viewing. While my parents and everyone I knew gushed about the performance (which was magnificent), to me the screenplay had delivered a verdict on modernity—and I was on the losing side.

Even at that age, I could sense that Fiddler had paskened, as if it were a halachic ruling, that modernity and assimilation were inevitable facts of life. I remember glumly hearing this discussed afterward in the men’s room: Assimilation would happen to all of us, and we’d better get used to it.

My own family was deeply observant, but I started to think, if that was our “fate,” why go through with the fight? Maybe our lives were the fantasy and the screenplay was the predominant reality. Maybe God would have to accept that, too—if Hollywood dictated so. The world had changed and Tevye was the mouthpiece—a new rabbi, a rabbi of reality installed by the gods of show business who had to be obeyed however haltingly. Modernity wins: That’s what Fiddler seemed to drive home to me at the age of 8.

And so a montage of Tevye images haunted me through my early years: Tevye alone pulls the wagon in an endless expanse of frozen mud, the people from Anatevka float on a barge, the rabbi recites the kaddish on a tundra-like patch of land, and finally, Tevye stands alone on his own personal Via Dolorosa when he turns around and sees the fiddler, who ekes out one more tune. The fiddler has the last word, so to speak, as though all that could remain of religion was a nign, a tune. Perhaps I, too, was doomed like Tevye, to fill out a role, as the last of sorts in a quixotic battle for a dying God and His troubled beleaguered people. Those uneasy, melancholy, disintegrating sensations kept me company for many years to the extent that I could not bear seeing Fiddler again.

*

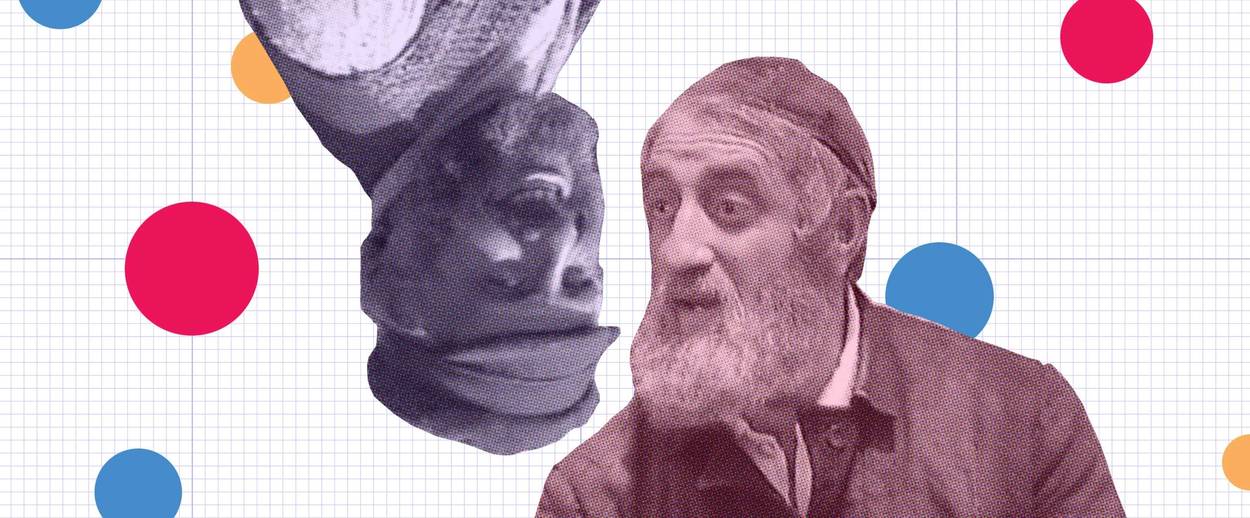

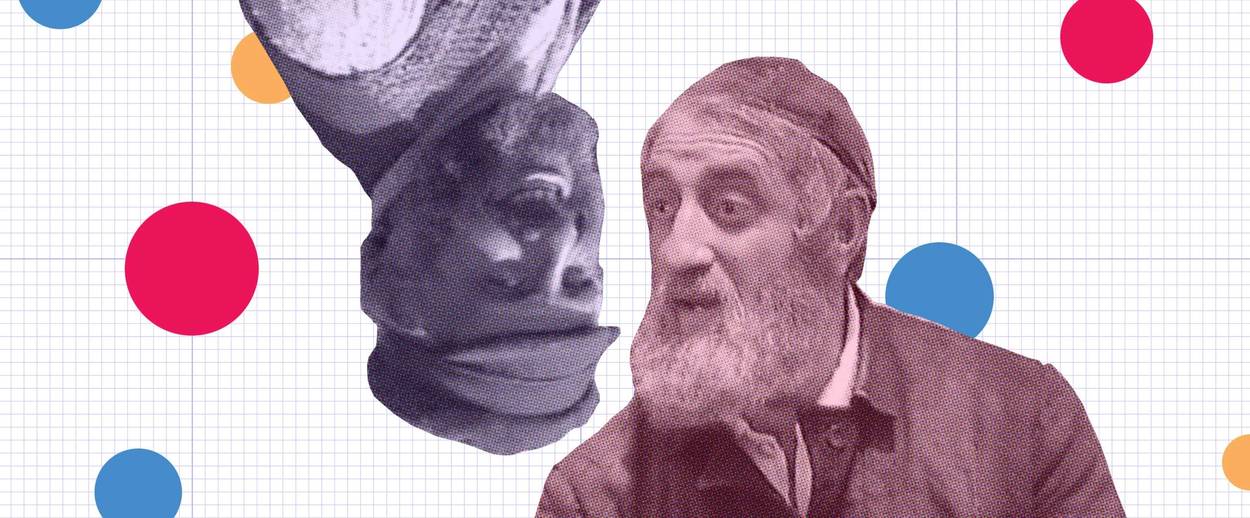

About two years ago, as my father’s life wound down to a close, my lifelong interest in Yiddish—his mameloshn—intensified. Since the love of Yiddish was yet another bond we shared, he suggested that we watch Yiddish films together. One of them was Maurice Schwartz’s classic Tevye—this year will mark the 80th anniversary of its release. The production was directed and filmed entirely in Jericho, Long Island, even as German tanks rolled into Warsaw in 1939. Both the timing (the movie was released just as the German genocide against our people began) and changing demographics (American Jews stopped speaking Yiddish) doomed the film to obscurity and neglect.

What happens to a book that is not read, a film that is not watched? It falls somewhere into the dusty stacks, frozen amber in the library of time. Somehow, however, Tevye was rediscovered in the late 1970s and was included by the National Film Preservation Board on its National Film Registry.

My visit with Dad began as it always did: I put the tumbler in front of him—a glass of seltzer, with ice. He wet his lips with the bubbles and then set the glass down. There was the slightest tremor in his hands as he held the glass. The signs were there all right, the yellowing on the back of the hand, the general unsteadiness. Who knew how long he was for this world? (The body knew: A few days before this visit, he had coughed without end. “Di hoost cheppe zich nit up,” he said. “The cough won’t let up.”)

We began to watch Tevye.

The film opens with Khava by the river. Peasant field hands catcall her; she clearly loves it. Fedya, her love interest, then sneaks up to her from behind and kisses her passionately. It is an open secret in Tevye’s household (but kept from Tevye himself) that Khava is flirting with a goy.

In the next scene the galach (the Russian Orthodox priest) comes to visit Tevye.

“You have beautiful daughters,” the priest says. “It’s a shame that because of their forefathers’ sins, they must suffer. You marry them off to khunyakes [losers] and they lose both this world and the next one.”

“You can keep your worlds—this one and the next one,” Tevye counters in a raised, agitated voice. “If any of my daughters married one of your boys, I should rather see her dead, or me dead. And if I had 10 daughters, I should rather see all of them dead than to marry one of yours.”

Dad looked at me. “Wow, Yisrael, this Maurice Schwartz’s Tevye pulls no punches. He tells it like it is. A real Poilisher Yid, a Varshaver”—a person from Warsaw, famous for sharpness, satire, and candor.

In a number of sequences Tevye shamelessly indulges in reverse racism, calling the gentiles liquor-swilling wife beaters. “They, our good-hearted goy friends and neighbors will be the first to join in the ‘simcha’ of a pogrom and come to break our windows,” he solemnly tells Khava as he vainly tries to scare her off her ill-starred romance.

As my father and I watched the Yiddish Tevye, we heard not a single song, nor was there any line that sought to make anything palatable. In fact, in Schwartz’s version the protagonist Tevye is far less ambivalent and far less “modern” in his thinking than the Tevye in Fiddler. True, his speech is saturated with the famous Hamlet-izing angst, but it is light on equivocation. He quotes (and misquotes) real sections of the Talmud. He is scarily ferocious in his denunciation of his daughter Khava when she marries Fedya, the gentile, and he never wavers.

In fact, that is pretty much what the whole film is about. Whole swaths that appear in later adaptations like Fiddler are not there. Here, Tevye has two daughters, not five. There is no Perchik, no Motel Kamzoil, no rabbi, no Sabbath blessing sequence, no chuppah, no Lazer Wolf, and certainly no “L’chaim” or “Tradition” or “Sunrise, Sunset” dance numbers—and no crazy Frume Sarah dream requiem. What’s more, the immortal icon of later versions, the “fiddler on the roof” himself, does not even exist in Tevye.

We watched more of Schwartz’s Tevye. There is a dramatic scene after Khava marries Fedya, and Tevye sits shiva in agony. The shock of the marriage “kills” Golda, and there is a deathbed scene where Khava is right outside the window in the cold as her mother takes her last breath.

The town elders evict Tevye from Anatevka. Khava tearfully returns to family, flock, and fold.

“I never stopped thinking of you, Tateh,” she tells her father. “My body was there with the goy, but my soul was here. Your religion is the greater one. I fasted every Yom Kippur and visited Mama’s grave.”

Tevye initially doesn’t forgive, but he eventually relents. The ending of Schwartz’s film seems to render a different verdict on modernity than Fiddler later did. Here, the family, the tribe, the religion, prevails.

Different endings for different audiences? It would take a different type of Tevye, an English-speaking one—in a Broadway musical with a roaring score and dance numbers—to speak to the appetite of the American Jews and gentiles for something Jewish-y. The Broadway Tevye of Fiddler clearly speaks to the goyim or to the assimilating Jew inside the Jew: Look how happy and gay the peasants are in their colorful costumes. Tradition, though venerated, is also conveyed with ironic distance: Can you imagine? A village, a matchmaker! A rabbi who blesses the czar and confers a benediction on a sewing machine? Look how nicely they sing on the Sabbath eve and the eternal, dependable yet tempestuous, shaky but beautiful lives they lived.

Fiddler on the Roof isn’t the first story from the old world to be sanitized or adapted for American audiences. For instance, there were several versions of Elie Wiesel’s Night that were presented to the public; the Yiddish version was more raw and unapologetic than the English. (Yiddish versions weren’t always simply darker: In the 1903 Yiddish version of Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, a fourth act was added with Nora happily returning to her husband. The sanctity of the family was one of the few absolutes of Yiddish convention.)

*

After we finished watching Tevye, my father took another gulp of seltzer and coughed long enough to scare me. Above us ceiling fans blew with force and the wisps of thinning hair on our respective heads fluttered in the artificial wind.

He dabbed his eyes. He felt for Khava.

I remembered him getting farklemt after seeing Fiddler on Broadway, but in this unsentimental Yiddish version of the story, where Khava’s goy-friend is made out to be a yold, a non-entity?

I cleared my throat. “Dad, I know it’s a bit un-Jewish to bash Sholem Aleichem, but don’t all these productions straddle the line between art, kitsch, and trash?” It’s all potato kugel for the masses, I told him.

My father gave me a look. “Are you human? How can you not feel for these people? This is love we are talking about!”

Love indeed. The problem was that Sholem Aleichem drove straight to my father’s Jewish heart, no matter how the stories were interpreted. There were the dependable tropes: Jewish homelessness and helplessness in a foreign land, the sharp evocation of Jewish traditions and exploitation of sentimentality together with a generous helping of suffering, the compulsive Jewish learning and compulsive Jewish teaching. My father could easily become flooded with the grief of mankind thwarting his ability—momentarily—to think it through. So yes, it was love all right, but it was love manufactured straight from the Yiddish theater on Second Avenue near the pastrami joints and the world of matinee idols Jacob Adler and Boris Tomashefsky. In the grips of sentimentality, one becomes like the old-time “unwashed” audiences of the Second Avenue Yiddish theater, helpless in the dubious charms of slapstick religion and schmaltz.

Being a rabbi might have taken my father from the masses, but there was something deep in him that understood the yearning of the common folk—people like Tevye—who were not scholarly but mastered the tone of being Jewish, family hysterics and all.

Yiddish, English, it didn’t matter to my father. He loved all things Sholem Aleichem. When they sang, he sang; when they wept, he wept.

As for me, in my sophisticated yet impoverished, frightened young boy mind, anybody with a loud voice could become my rabbi. That is why the Broadway Tevye of Fiddler frightened me so.

Tevye to me was like a “damaged rabbi” who had become unmoored from tradition. He suffered from the outside—pogroms, poverty, dispossession, but on the inside, after losing his daughters, he had become completely dislocated. All that was left was him and the fiddler. Miles from humanity, in a Siberian winter, Tevye alone pulls the wagon.

As a therapist, and an adult, I understand the psychological reasons behind what I felt so keenly on an emotional level as a child: More than death, people are afraid of disintegration, that they will be lost to themselves and to their tribe.

*

For more than 40 years I had avoided seeing Fiddler productions. On that winter day two years ago in my father’s house, I did not want to see the end of Schwartz’s movie with my father. I feared the old terror would strike me. I would have to see Tevye trudge off alone and broken into the tundra. With the final farewell with my father soon at hand, it would be too much for me.

But, surprise! In Schwartz’s version Tevye packs up to Palestine to sell milk and cheese and visit the graves of the ancestors, and most of all to study the Talmud, his faith intact—even more so. He may have been thrown out of the Pale of Settlement or some Polish hinterland, but he was not lost to himself. Unexpectedly, I was heartened by the film exactly where I had been expected to plunge. My father and I would soon be lost to each other, but I took strength from the film: Perhaps we would not be lost.

The Broadway Tevye of Fiddler settles in America. One imagines in a generation, he melts into the fabric, his children join a suburban temple and on Yom Kippur they weep among their riches. The man who sang “If I Were a Rich Man” no doubt will see his descendants become wealthy. Yet all the riches of Babylon cannot stop a Jew from feeling empty. By the waters of Babylon we sat down and wept. We wept because we had money. We had money, but we were lost—in exile.

After I saw the film, I looked up the last line in the original 1916 play, which all the Tevye and Fiddler productions are based on. “Tomorrow may find us in Yehupetz, Odessa, or America … Have a good trip,” Tevye says, to the Jewish people. “Say hello for me to all our fellow Jews and tell them wherever they are not to worry: The old God of Israel still lives.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Alter Yisrael Shimon Feuerman, a psychotherapist in New Jersey, is director of The New Center for Advanced Psychotherapy Studies. He is also author of the Yiddish novel Yankel and Leah.