The Boy From Rangoon

How my grandfather landed at Yeshiva University

As a child, I loved looking through my grandfather’s Yeshiva University yearbook, scanning the faces of all those earnest young men in the class of 1938. The snapshots show them in the caps and gowns that recall a monastic era, and in the kippot and tzitzit that mark them as observant Jews, a perfect synthesis of torah u’maddah, Judaic knowledge and Western secular study.

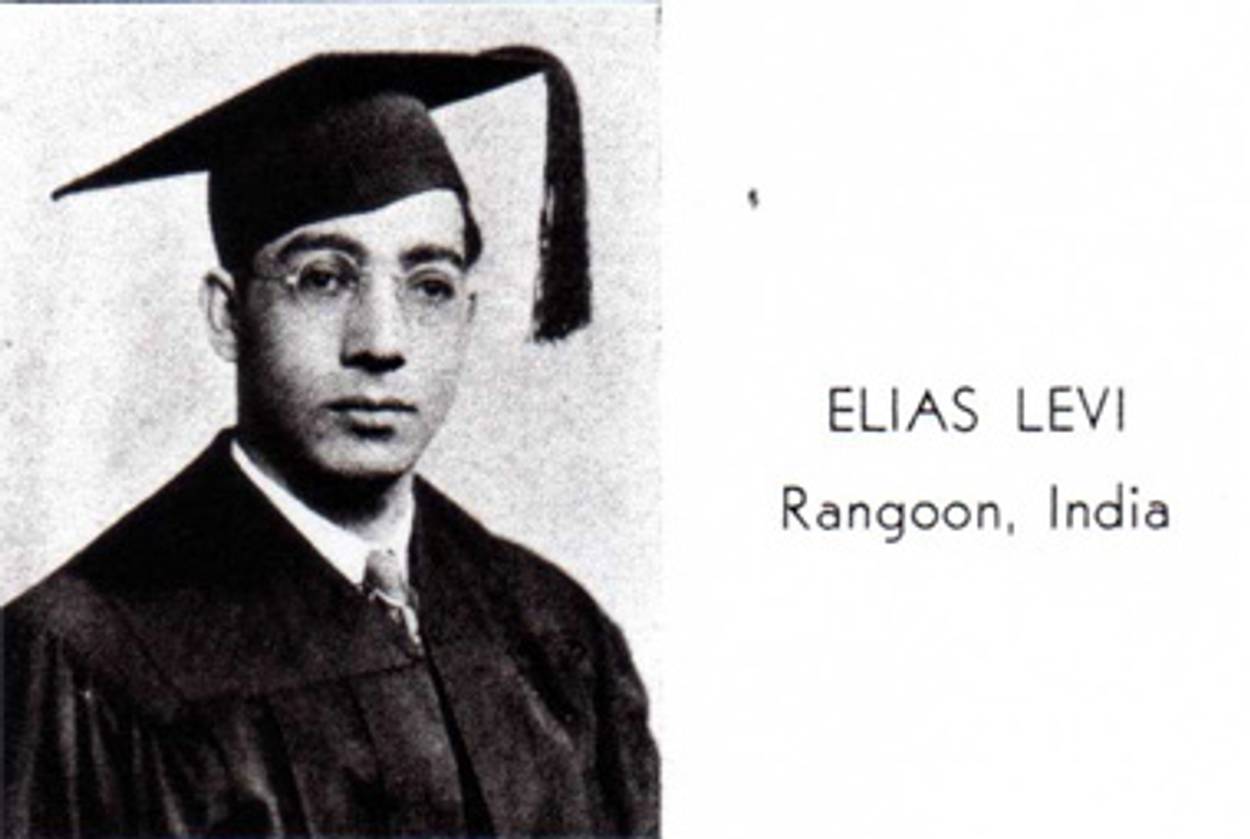

The yearbook records another kind of synthesis as well: that of the Ashkenazi and Sephardi worlds. Yeshiva today boasts a Sephardic studies program, a Sephardic community program, and an Institute of Sephardic studies. But none of those existed when my grandfather, the school’s first Sephardic student, attended. (To clarify, my grandfather was Mizrahi, the term identifying Jews from Arab lands, though members of his family believed their ancestors arrived in Iraq from Spain. At the time of my grandfather’s matriculation at Yeshiva, university officials identified anyone of non-Ashkenazic origin as Sephardi.) On page 34 of his yearbook, nestled among the photos of graduates from Albany and Atlantic City, from Brooklyn and Baltimore, is a photo of my grandfather, Elias Levi, with “Rangoon, India” listed as his hometown. All his official college papers erroneously locate Rangoon in India; evidently Burma was so far off the Yeshiva map, it was invisible.

My grandfather was not like my friends’ grandfathers. He told stories of burrahutti and chotahutti, which I later learned were Hindi words for elephants. As a rabbi, he would visit congregants in the hospital, entering the room with a sweet “ahlan u’sahlan,” and whisper Arabic to the men and women with walnut-colored, papery faces. It was forbidden for girls in my family to pierce their ears, but my grandfather, a paragon of Orthodoxy, considered belly dancing high art.

Elias Levi was born in 1910 in Baghdad, during the month of November, though he didn’t know the exact date. On the principle of “la bead harkim wulla bead hakim” (Judeo-Arabic for “not in the hands of the authorities and not in the hands of the doctor”), Jews concealed birthdays and other identifying details because of a widespread belief that doing so would protect them from Muslim authorities.

Elias was the second of nine children born to Ruhama and Suleiman HaLevi (“HaLevi,” the Levite tribal designation, was adapted in my grandfather’s generation to the last name Levi). Like his father and grandfathers, Suleiman was involved in religious learning and earned the title “hakham,” wise one. A mystic and healer who refused to take money for his services for fear the transaction would make him lose his power, Suleiman made his living selling sweets in the streets of Baghdad.

In the spring of 1913, my family left Iraq, escaping the anti-Semitism that reached a terrible pinnacle there in the 1941 Farhud (pogrom). Most Iraqi Jews went to Calcutta or Rangoon. Though my family was poor, subsisting mostly on rice and tea with chicken on Shabbat, they were welcomed by the Burmese, whose culture was then relatively tolerant. My grandfather and his siblings shared stories with their children and grandchildren of the lush landscape, loaded with teakwood and silk and oil, their fine education at the feet of British emissaries, and the baby elephant their ground-floor neighbors kept as a pet in front of the apartment house. Maintaining the family interest in religious life and Jewish history, Elias founded the Rangoon Zionist Society when he was still in high school, and published articles in Jewish journals in Shanghai, Bombay, and London.

My grandfather had a scholarly and spiritual temperament. It was no surprise that he decided to become a rabbi and play a role in the revivification of Sephardic Jewry. The community urged him to go abroad for rabbinic training—there was no place for him to become ordained in Burma—but it was understood that after his studies, he would return to Rangoon to take up the position of Chief Rabbi.

Meanwhile, the articles he’d written for Jewish publications had brought him to the attention of Rabbi David Miller, an author and philanthropist who left his East Coast pulpit and moved to Oakland, California, where he wrote books urging fidelity to the Orthodox practices of family purity and Shabbat observance. In 1933, Miller wrote to Benjamin Koenigsberg, an attorney and an alumnus of Yeshiva Etz Chaim, the forerunner of Yeshiva University, about “a certain young man, Mr. Elias Levi…[who] has corresponded with me for years.” The letter is in Yeshiva’s archive, which I recently searched to learn more about my grandfather. “He is a young man about 22 years old, apparently with remarkable ability,” the letter continues, “anxious to acquire a higher Jewish education to qualify himself as a Rabbi, as a leader to help our scattered, most forgotten brethren in India; to enlighten them with the great merits of our Jewish religion and of our precious inheritance. He sought my advice as to how and where he could obtain such an education. In view that he is an English speaking person, I advised him to enroll in the Yeshiva College of New York in preference to European or Palestine [sic] institutions of Jewish learning. He accepted my advice and he was preparing to go to New York saving every penny of his meager salary as an accountant in a bank for the expense of transportation.”

My grandfather applied to and was accepted by Yeshiva, which covered his board and tuition. But the American consul in Rangoon refused to grant him a visa, on the grounds that since Yeshiva’s offer did not provide for petty expenses, there was a danger that my grandfather might become a burden on the state. Miller and Koenigsberg undertook a frantic letter-writing campaign, guaranteeing, mostly out of their pockets, support for incidentals, including laundry, clothing, and medical treatment. The Young Judean League of Burma (then the country’s major Jewish organization) got involved, and the case drew attention around the Jewish world. “We are fully conscious of the great boon that Yeshiva College is conferring on Burma Jewry,” wrote J.E. Joshua, the League’s president, in a letter to Rabbi Bernard Revel, the college’s president in 1932. “It will interest you to know that we have received the appreciation of the Very Rev. Haham Dr. Moses Gaster [Chief Rabbi of the British Sephardic community] in our undertakings and Mr. Levi has been invited to see him on his way to New York. This great experiment is being watched with interest by responsible leaders in the Orient.”

Looking through my grandfather’s papers, I was struck that even in the most bureaucratic back-and-forth correspondence, the language that these men used suggests that bringing the 22-year-old to America was a sacred mission, “a Holy cause on which the spiritual future of Eastern Jewry depends,” as Joshua wrote. The response to his plea was equally formidable. “In spite of the gloomy picture you give [of conditions for Jews in Burma], I have great hopes for the strengthening of our faith,” Revel replied. “The very existence of the Young Indean [sic.] League, and the spirit that breathes in your letter and that of Mr. Elias Levi, is a sign that the fervor of our ancient prophets and seers, which has sustained Israel through the ages, still burns in the breasts of our scattered brethren.”

Two years and hundreds of letters later, all the pieces came together. My grandfather secured Koenigsberg and Rabbi Miller as guarantors (each of them, in turn, had to secure their own guarantors), and my grandfather’s editor at Israel’s Messenger in Shanghai, N.E.B. Ezra, helped him obtain an entrance visa. In 1934, my grandfather traveled by ship from Rangoon to Shanghai (where he was met by Ezra), by ship to San Francisco (where he was met by Miller), and then by train to his final destination. One year later, Koenigsberg wrote to Rabbi Miller: “I invited Levi downtown to address my Young Israel at a Friday night lecture on ‘The Jews in India.’ He prepared his subject very well, and made a very good impression upon the audience numbering about six hundred, undoubtedly the largest he ever addressed….The pleasure I derive in hearing about [Levi] is sufficient for Olam Hazeh. I am hoping that when Levi succeeds in his studies, our efforts will be fully appraised in Olam Habah.”

Meanwhile, the “great experiment” of bringing a Sephardi student to Yeshiva was already being duplicated. Close on the heels of Elias Levi was Yeshiva’s second Sephardi student, Rahmin Sion, a native of Basra, who graduated in 1939.

Sadly, my grandfather’s goal of becoming Burma’s chief rabbi was not to be. In 1941, the Japanese invaded Burma, and most of the Jews there—including my family—fled to India, Mandate Palestine, England, and America. My grandfather stayed in the United States and spent his career leading Sephardic congregations in several American cities. He was the first pulpit rabbi at Kahal Joseph in Los Angeles, the only congregation on the West Coast to follow Baghdadi customs. He continued to publish articles, to lecture, and to maintain ties with Jewish communities throughout the world.

My grandfather died in 1987, but I’m certain that if he could see what I saw on the Yeshiva University campus—how its Sephardic presence had blossomed in the decades since his first pioneering days there—he would shake his head, smile, and offer, in his lilting accent, a most sincere “hazak u’barukh.”

Margot Lurie is a Maytag Fellow at The Iowa Writers’ Workshop. She lives in Iowa City.

Margot Lurie is associate editor of Jewish Ideas Daily. She last wrote for Tablet about her grandfather, Yeshiva University’s first Sephardic student.