The Holocaust Book We Need Right Now

‘White Bird,’ a graphic novel for kids, stresses the importance of political resistance—then and now

Regular Tablet readers have heard me wail, multiple times, “Enough with the Holocaust books for kids!”

Look, I am certainly not anti-Holocaust-education. In fact, I’ve always maintained that it’s vital to teach the Holocaust in an age-appropriate, responsible way. But I’ve also said repeatedly that, when so few children’s and young adult books are published about Jewishness and Judaism, the relentless focus on the Holocaust is harmful to us and to the wider world. Why, when we have a 6,000-year-long story, is there so much focus on one of the worst things that ever happened to us? The Holocaust isn’t the sum total of who we are. Where are the books introducing kids to Jewish historical figures who are not Ruth Bader Ginsburg? Where are the stories grounded in Jewish folklore and mythology, in non-Ashkenazi Jewish culture, in Orthodoxy? Where are the books reflecting the diversity of the Jewish American experience?

The problem with an obsessive Holocaust focus is that, given how few Jewish children’s books are published by mainstream publishers, vital stories go untold. (I mean, OK, there are a lot of picture books about Hanukkah. But most of them suck, and Hanukkah isn’t the holiday we should be focusing on anyway. Few non-Jews—and let’s be honest, not enough Jews—know that Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, Sukkot, and Shavuot are way more important than Hanukkah.) And the non-Holocaust/non-Hanukkah Jewish middle-grade and young adult books we do get are often reminiscent of the “problem novels” of the 1960s: Jewishness is a source of trouble and trauma, not sweetness and comfort.

(I am, of course, generalizing. Kind of. For a decade now I’ve been writing about great Jewish children’s books about a variety of topics, and even ones in which—oy, a mechaye—the characters’ Jewishness just matter-of-factly is. There are books from Jewish publishers—books written by us and for us, often on a shoestring budget—that endeavor to tell a multitude of stories. But overall, jeez: SO. MUCH. HOLOCAUST.)

Now, though, I’m not so sure. Now that anti-Semitic hate crimes have suddenly skyrocketed. Now that I was distracted from Yom Kippur services by an unguarded side door, despite the bomb-sniffing dog, security personnel, and metal detectors in the front, even though I did not know at the time that there had already been a Yom Kippur shooting outside a different synagogue. Now that a 2018 study found that 22% of millennials have never even heard of the Holocaust. Now I must amend my statement: We need superlative Holocaust books. There is still no place for mediocre ones—if these were once a mere annoyance, they’re now an urgent problem. No more books that offer ahistorical feel-good fantasy or that destroy hope, no more books that get history wrong, no more books that focus obsessively on Anne Frank (just do Anne Frank the courtesy of reading her own book!), no more books that universalize entirely too much from our particular lived experience.

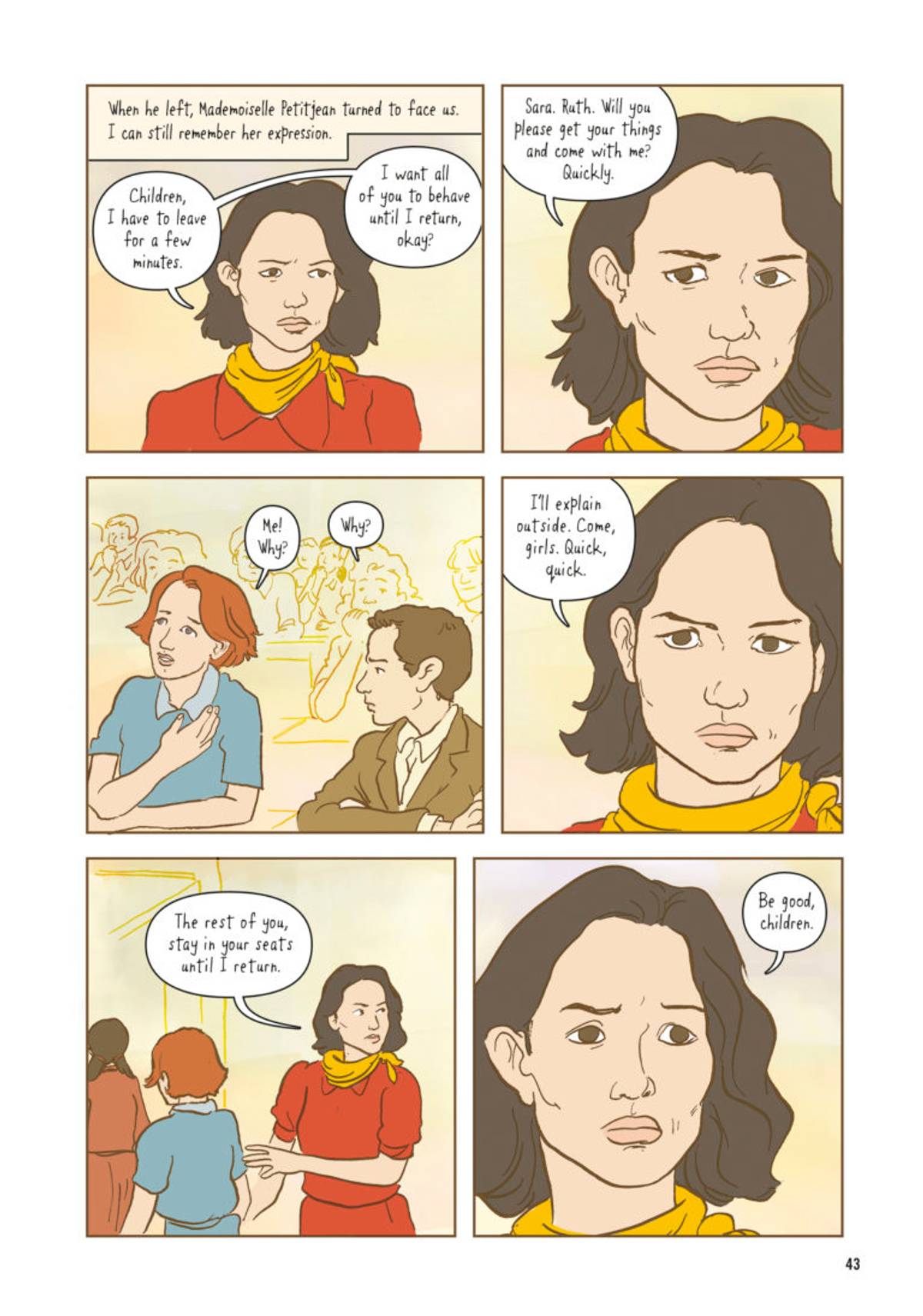

White Bird is the Holocaust book we need right now. It’s a graphic novel by R.J. Palacio, the author of the mega-bestseller (and movie) Wonder, and inked by cartoonist Kevin Czap. The publisher recommends White Bird for readers 8-12, but I wholeheartedly recommend it for young adult and grown-up readers, too.

White Bird is the story of Sara, a character introduced in Auggie & Me, a collection of three short stories from the perspectives of three kids who appear in Wonder. You needn’t have read Auggie & Me to appreciate White Bird, and in fact, it’s probably better if you haven’t. (That said, it’s not much of a spoiler to say that Sara appears in “The Julian Chapter,” narrated by Julian, the kid who bullies Auggie, who has severe facial deformities. “Sure, sometimes I make jokes,” Julian shrugs. “People have to lighten up a little! Stop being so sensitive!” But when Julian learns his Grandmère Sara’s history—which she hasn’t even told her own son—he becomes determined to be a menschier person.)

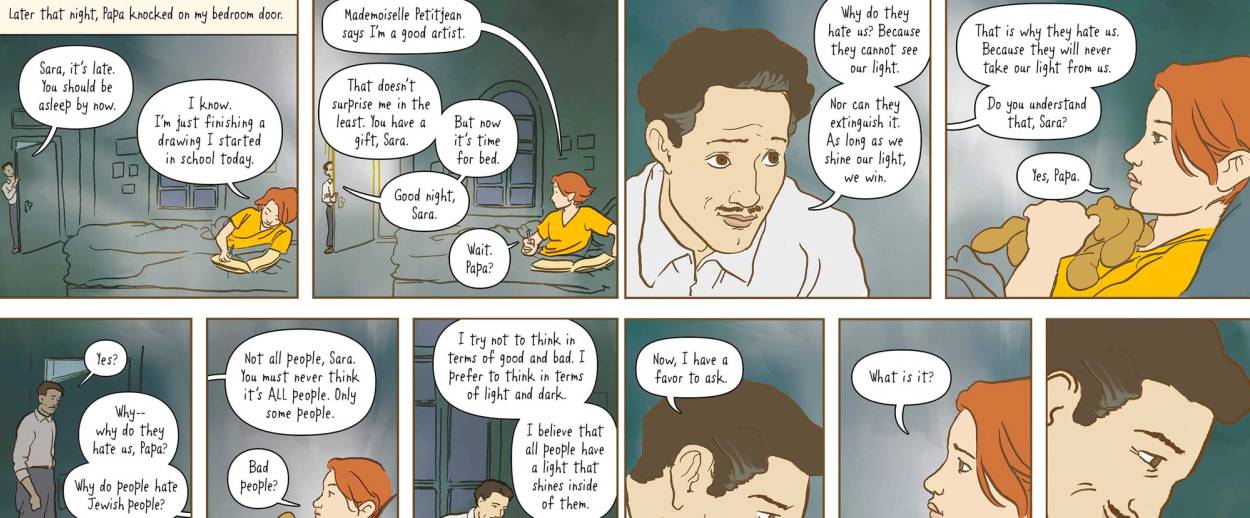

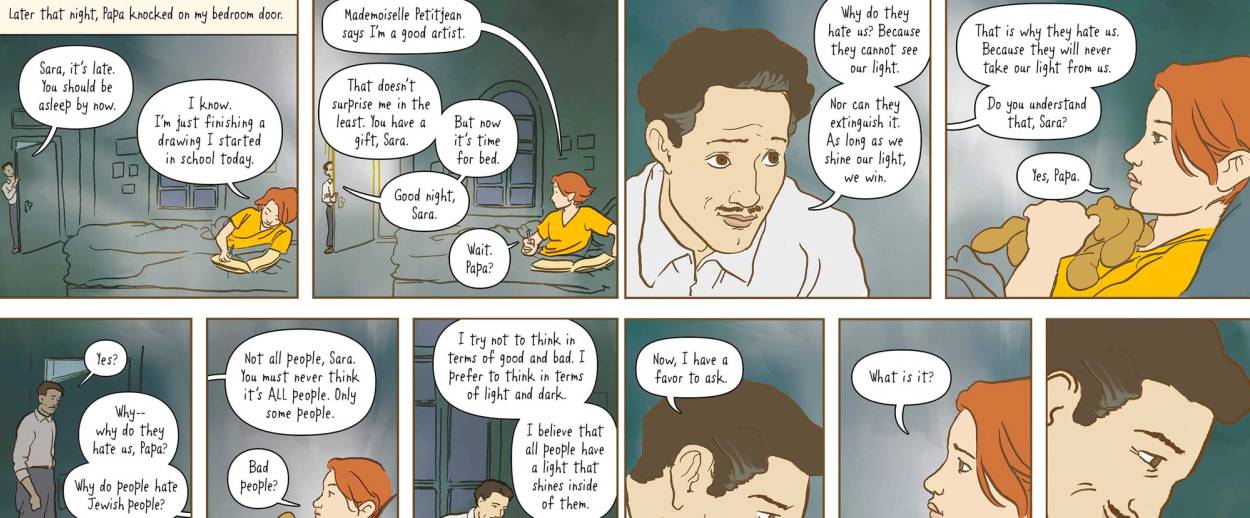

The graphic novel opens with Grandmère Sara (in chic purple cat’s-eye glasses) FaceTiming Julian, who is still thinking about the way he’d treated Auggie. In response, she begins to tell him a story of her own; the narrative flips back to Sara as a spoiled, frivolous rural French girl whose life gradually changes under Nazi occupation. When Sara’s school is raided and the Jews of her town rounded up, she’s saved by a classmate she’s always been dismissive of—a boy named nicknamed Tourteau, turtle, because of the way polio has withered his legs and he moves slowly, sideways, on his crutches. He leads her to safety through miles of sewers—her classmates have always made fun of him for having a sewer worker for a father, insisting Tourteau smells, though he doesn’t—and he hides her, with his family’s help, in their old barn, for over two danger-filled years.

Wonder was a bestseller not (just) because it was an anti-bullying story, but because it was a kid-friendly, easy-to-read page turner. So is White Bird. There’s excitement, blood, heroism, chocolate, fields of bluebells, a possibly supernatural wolf, a kiss, a desperate flight through a forest, a dose of sleeping powder. It isn’t ponderous, like so many Holocaust books. What good is an educational book if no one willingly reads it? And the message we can all choose to stop our bullying behavior and be kinder is welcome, without coming off as too thuddingly obvious.

Neither Tourteau nor Sara is perfect. She’s a self-absorbed, childish, pretty girl and he is impulsive and has a temper. When she starts to idealize him because of his disability, he snarls, “Crutches don’t make me brave! They make me walk!” The book is careful not to make him a saint, a character who exists to illuminate the main character’s nobility.

Like Anne Frank, Sara records her feelings in a diary—in her case, with sketches as well as words. Peering between the rotting slats of the barn, she notes, “I could see the edge of the woods, the fields, and the sky. It reminded me of how beautiful the world still was. Even if physically I couldn’t go out into it anymore … my imagination could still roam … as free as a bird.” (The book’s title comes from a line in Muriel Rukeyser’s poem “Fourth Elegy. The Refugees.”)

White Bird draws an explicit parallel between the plight of the Jews in the 1930s and the plight of refugees today. It also raises an eyebrow at religious figures who stay on the sidelines: “When will God make this evil end?” a pastor asks. “It’s not up to God to make it end,” a Resistance fighter replies. “Evil will only be stopped when good people decide to put an end to it. It is our fight, not God’s.” Later, that pastor joins the Resistance. The book posits that activism can help us cope in an unjust world.

In an afterword, Tablet contributor Ruth Franklin, author of A Thousand Darknesses: Lies and Truth in Holocaust Fiction, writes, “White Bird ends with a call to resist contemporary manifestations of prejudice and xenophobia. One needn’t necessarily agree with the direct line the book draws from Nazi Germany to current events to be moved by its encouragement to stand up against tyranny and cruelty wherever we may find them, from the treatment of refugees to the tormenting of a disabled child in school.” One needn’t necessarily agree with Palacio’s direct line, but those who disagree tend to leave one-star Amazon reviews snarling that “this book has a political agenda and compares Trumps [sic] immigration laws and practices to Hitler and the Holocaust. I hate it when children’s books try to indoctrinate our kids. Leave your political views out of it!” Today, I’d argue, not taking a political stance is taking a political stance.

The book shines in its extensive back matter, which reveals the vast amount of work Palacio, who is not Jewish, did to research and write the book. She’s conscious of her outsider status in an era of #ownvoices activism. She notes that while her Jewish husband couldn’t recall a time in which he didn’t know about the Holocaust, she herself grew up knowing about Nazis only from Hogan’s Heroes and The Sound of Music. Not until she stumbled on concentration camp photos in a Life magazine coffee table book did she become aware of Nazi atrocities. Implicit here is the idea that while Jewish kids are getting vital education in their own history, non-Jewish kids aren’t.

Palacio is also careful to make a Jewish character the story’s focus; too many Holocaust books for kids center the heroic goyish rescuer. She discusses T4, the Nazi program to eliminate people with disabilities, and the Armée Juive, a collective of Jewish Resistance fighters; she’s trying to show both that the Nazis wanted to eliminate other groups besides Jews and that Jews weren’t merely passive victims, facts that not enough people—kids and adults alike—know.

Palacio also painstakingly shows us the real-life backdrop to her fictional story. The characters would have been taken to the transit camps of Pithiviers and Drancy as well as to Auschwitz. Sara’s parents allude to the Vel’ d’Hiv roundup in May 1942, in which 13,000 Jews, including more than 4,000 children, were detained in a Paris stadium in filthy conditions, without enough food or water, before being sent off to the camps. The book’s pastor, who ultimately joins the Resistance, is based on André Trocmé, a real clergyman who preached against Nazism from his pulpit in Le Chambon-sur-Lignon; the non-Jewish teacher who willingly accompanies Jewish children rounded up by the Nazis to their deaths is based on Trocmé’s nephew Daniel, a school principal who chose to join his imprisoned Jewish students and died in Majdanek at the age of 34. Both are recognized by Yad Vashem as Righteous Gentiles. Even the wolf in the story has an analog: It’s based on The Beast of Gevaudan, a purportedly man-eating wolf that roamed the forests of the Margeride mountains in the 18th century and may have been the source of the legend of Little Red Riding Hood.

Palacio also provides a bibliography, suggestions for further reading, and a list of organizations and resources including Anne Frank House, the ADL, the USC Shoah Foundation, the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum and more. (I wish she’d left off the controversial Anne Frank Foundation for Mutual Respect, we can’t have everything.)

I remain wary of the glut of Holocaust lit for kids. But I welcome thoughtful, readable books that contribute to a sadly necessary national conversation. This is one.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.