A History of Jewish Day Schools

Once demonized as the community embraced public schools, they eventually came into their own by teaching ‘Judaism and Americanism’ side by side

These days, the day school is the darling of the American Jewish community, the apparent antidote to everything that ails its members. If only more American Jewish children enrolled in one, common wisdom has it, the contemporary Jewish condition would be manifestly different: glowing with good health instead of listless and besieged.

When seen from that vantage point, it might look as if the day school has been among those institutions, like the synagogue, that have always been with us. History suggests otherwise: In modern America, Jewish day schools were once the exception, not the norm. Scant in number, they were also frowned upon by most American Jews, demonized rather than lionized.

Well into the postwar era, the Jewish community put its faith in the public school, an institution that “not only turns out men. It makes the American people,” or so trumpeted The New York Times in 1894. The public school, not the day school, was American Jewry’s beloved. “There is no greater friend of the American public school than the Jew,” Rabbi Abraham Simon of Washington Hebrew Congregation enthusiastically noted a few years later. “There is none more eager to grasp its opportunities and none more grateful for its privileges.”

At the time, America’s Jews understood all too well that the public school was both the ticket to modernization and the price they had to pay to become full-fledged Americans. Where else would their children learn their ABCs along with what Rabbi Simon catalogued as “honor and honesty, chivalry and cleanliness, humaneness and justice, personal purity and social service”?

In their determination to belong, the nation’s Jews overlooked Americanization’s often heavy-handed, cruel, and insensitive exactions as well as the physical shortcomings of the public school, whose facilities, especially within immigrant neighborhoods, were frequently overcrowded and poorly ventilated, rendering its young charges dull and sluggish. Then again, they had little choice. Where the public school, that “miniature republic,” spoke of freedom, an exclusively Jewish facility—a Jewish parochial school—smacked of the ghetto, or, worse still, of sectarianism.

It didn’t help matters that, as a rule, Jewish educational institutions in the New World were both supplemental and subpar, their physical and curricular limitations so pronounced that no one ever rallied to their side, much less cheered them on. Admittedly, there wasn’t much to cheer about. Even the dreariest public school building looked like a palace compared to the dark, dank afternoon Hebrew schools or Talmud Torahs, where hapless male students, one of their number wittily recalled, were taught everything from “aleph to bar mitzvah” by woefully underpaid and poorly trained instructors. “Almost every immigrant put ashore at Ellis Island will do,” added one disgruntled eyewitness, noting that the characteristic mode of instruction was to “outshout” everyone else, leading inevitably to “veritable bedlam.”

Under the prevailing circumstances, it took enormous vision, leavened by a giant leap of faith, to imagine a Jewish educational institution that could hold its own against the mighty public school and do right by American-born boys and girls, all the while offering first-rate instruction in Jewish subjects. The prospect of an integrated curriculum in which youngsters would learn Chumash (Bible) at 9 a.m., Mishna at 10 a.m., civics at 11, and American history an hour later, only to emerge at the end of the day the better for it—and their American accents intact—seemed like pie in the sky, a quixotic and untenable proposition.

Besides, a Jewish day school was risky business, undermining American Jewry’s integration into the body politic. Drawing on harsh language, even the most committed of Jewish professionals looked askance at the prospect, which they branded dangerous and “toxic.” American Jews should “banish” the idea of a Jewish day school education from their minds, declared Samson Benderly, one of the interwar community’s leading educators. “What we want in this country is not Jews who can successfully keep up their Jewishness in a few large ghettos, but men and women who have grown up in freedom and can assert themselves wherever they are. A parochial system of education among the Jews would be fatal to such hopes.”

Not everyone agreed with Benderly’s assessment, or, for that matter, with the cultural assumptions on which it was based. Some, like the early-20th-century founders of Yeshiva Tiferes Bachurim in Brooklyn or Mesivta Tifereth Jerusalem on the Lower East Side, had other ideas about Jewish education. For them, what was critical was continuity: the importation and transplantation of the East European model of Torah study to the New World. Training their sights on a small, exclusively male and highly traditional segment of the population—the “priest class,” one ill-disposed observer called them, dismissingly—they stood their ground, and remained apart from most of their American Jewish contemporaries for whom a separate educational system remained a no-no.

Little by little, though, something started to give: Jewish day school education became an increasingly attractive option. Between 1917 and 1939, American Jews established 23 such institutions in the greater New York metropolitan area alone. What fueled their efforts was the sobering realization that hardly any committed or “sturdy Jews” emerged from the prevailing system in which Jewish education played second fiddle to the public school. Heightened external receptivity to the notion of cultural pluralism, in turn, eased their way. A philosophy of the commonweal that made room for ethnic diversity at the grass roots and in the classroom, it defined heritage, tradition and custom as a gift rather than an obstacle. Under its impress, what was once unthinkable became doable.

Political turmoil abroad also helped to transform the day school into a viable alternative to the public school, depositing on American shores a critical mass of European Jewish families long familiar with and receptive to sectarian forms of education.

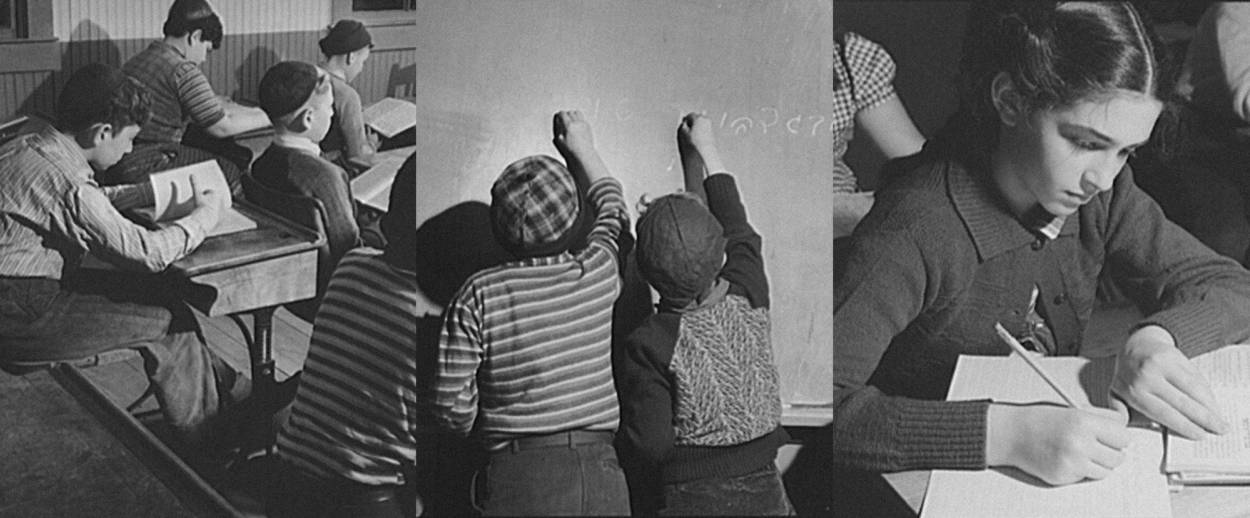

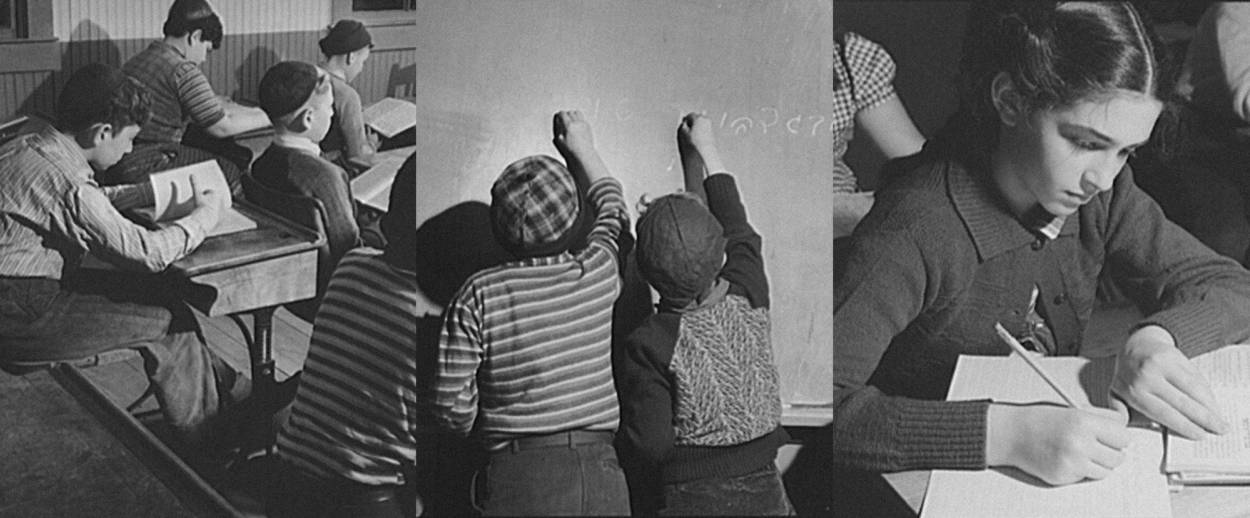

Concomitantly, the field of Jewish education came into its own, giving rise to a new generation of professional Jewish educators. In contrast to the reluctant recruits of yesteryear, these teachers “in appearance, speech and training exemplify the bearing of an American Jewish gentleman,” proudly related Rabbi Joseph H. Lookstein, the founder of the Upper East Side day school known initially as the Ramaz Academy, who made a point of hiring them.

From its well-mannered faculty and high-toned name to its cultivation of a “wholesome and integrated American Jewish personality,” everything about that institution—and its counterparts, among them the Yeshivah of Flatbush and Boston’s Maimonides School—spoke of modernity. No reason, then, for American Jewish parents to bolt at the gate. Inside the day school’s well-maintained precincts, happy, contented, American Jewish boys and girls thrived in an atmosphere in which “Judaism and Americanism” were boon companions rather than oppositional categories.

In the years that followed, especially in the wake of the Shoah and the rise of the State of Israel, Jewish day schools gained in both number and collective esteem. Once marginalized and derided, they came to be seen, in the words of the Orthodox Union, as the “most exciting and hopeful phenomenon in Jewish life in America.”

*

Statistics bore out that optimistic assertion, as did the emergence of Conservative and Reform-affiliated day schools. By the late 1990s, according to one census, American Jewry could boast nearly 670 Jewish day schools; the most recent tabulation, in 2013-2014, puts that number at 861.

It’s anyone’s guess as to what the future holds. Some seasoned observers, pointing to the increasingly exorbitant costs of a day school education, worry about the economics of sustainability; others, pointing to decreasing denominationalism, worry about institutional stability. And still others note that, despite their postwar proliferation, day schools still do not attract the overwhelming majority of school-age American Jews.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Jenna Weissman Joselit, the Charles E. Smith Professor of Judaic Studies & Professor of History at the George Washington University, is currently at work on a biography of Mordecai M. Kaplan.