The Valley of Dry Bones

I learned how to be a Jew at a black church

One Saturday afternoon in 1978, my father asked me to drive him from our home in New Jersey to Kennedy Airport in Queens, from which he was flying abroad on a business trip. I dropped him off at the TWA terminal and got on the Belt Parkway to head back. Almost immediately, though, I rolled to a halt at the tail end of a traffic jam that stretched ahead as far as I could see. I didn’t know this part of the city other than its expressways, so while idling in the unmoving mass, I pulled a map out of the glove compartment and looked for alternate routes. It seemed like all I had to do was take the next exit onto Conduit Boulevard and then veer onto Linden Boulevard, which would carry me across Brooklyn toward the Verrazano Narrows Bridge and ultimately back to my evening plans with friends from my newspaper job in Jersey.

Relieved to be rid of the traffic jam, I lead-footed the accelerator and raced along Conduit and onto Linden. Maybe fifty feet ahead of me, I could see a panel van moving at about the same speed, nothing to worry about. Just then, the rear doors were flung open and I saw a pair of arms shove out a woman. For a split second, I registered the scene and the gruesome insight it afforded: a human being could bounce off pavement something like a basketball. Jolted back into the moment, I swerved hard to avoid hitting the woman and nearly ran off the road. By the time I had righted my car, with my heart and lungs pumping like pistons, I was too far down Linden Boulevard to stop and give help. So I drove up and down the side streets, searching for a cop. There wasn’t one to be found.

I did not realize it at the time, but I had just made the acquaintance of the East New York section of Brooklyn. I would not return for more than a decade, until the morning in October 1989 when I rode the subway from Manhattan until I was the last white person aboard and made my tentative, wary way on foot a dozen blocks to Saint Paul Community Baptist Church.

At that point, I was in the very early stages of working on a book about an African American church—so very early, in fact, that I was still trying to choose the right one. I had not come to this topic for particularly religious reasons. I was the secular son of a family of proud, fervent atheists. My parents, though, had been die-hard liberals, devoted to the civil rights movement, and I was fascinated to find out how the black church, as the central institution of that crusade, had adapted to the challenges of the 1980s: white flight, the crack and AIDS epidemics, deindustrialization, Reagan trickle-down economics.

In those maladies, as I soon learned, East New York abounded. The neighborhood’s police precinct had tallied nearly a hundred murders that year, and its officers wore T-shirts emblazoned, in grim bravado, THE KILLING FIELDS. East New York had almost always been a neighborhood of the working class and the working poor, but in just a few years of the mid-1960s, aggravated by property crime and alarmed by block-busting real-estate agents, its longtime population of Italians and Jews fled. In their place came blacks, some of them educated and aspirational, some of them welfare cases dumped by city policy into distant neighborhoods. Another city policy of the time went by the deceptively tepid name of “planned shrinkage.” It meant, in practical terms, that mayoral administrations believed that nothing could save East New York and the adjacent slum of Brownsville, that any money spent on public services there would be wasted. The cost-effective solution was for East New York and Brownsville to die off and start over from scratch. When Boston’s then-mayor Kevin White visited Brownsville in 1968 and beheld its landscape of abandoned buildings, its fields of waist-high weeds and broken bricks, he said that he had seen “the beginning of the end of our civilization.” He could just as justifiably have read the first verses from the thirty-seventh chapter of the Book of Ezekiel:

The hand of the Lord came upon me. He took me out by the spirit of the Lord and set me down in the valley. It was full of bones. He led me all around them; there were very many of them spread over the valley, and they were very dry. He said to me, “O mortal, can these bones live again?” I replied, “O Lord God, only You know.” [Jewish Publication Society translation]

I did not know then about the prophet Ezekiel and his vision of the Valley of Dry Bones. Worse, I didn’t know that I didn’t know. Nothing in my upbringing had imbued me with any familiarity or comfort with Judaism. During Passover when I was probably ten or eleven, my mother took me to visit an elderly relative who happened to be observant. She pointed to her stovetop, covered in aluminum foil. Clearly meaning to toss a precocious child a softball question so she could then pretend to be impressed, the relative asked, “Sammy, do you know why the stove is that way?” I stumbled, completely oblivious to the tradition and requirement of ridding a house of chametz, of leavened products, during Passover. “Because it’s easier to clean up?” I finally stammered. Taking pity, the old woman gave me a candy anyway. During Hanukkah, we lit our menorah on a Ping-Pong table in the basement, a direct contradiction of the religious injunction that the candles and the miracle they represent be made visible to the outside world. My brief, yearning dalliance with religious practice, when I sought to become a bar mitzvah, ended with the rabbi trying to shake down my father for a bribe. We located another rabbi to perform the ceremony, but the damage had been done. My parents’ critique had been ratified. Religion really was, as they always put it, “sectarian and materialistic.”

So during high school or college, when an aunt of mine bought me a subscription to The Jerusalem Post’s international edition, I had no clue whatsoever why its comic strip was called “Dry Bones.” In my early thirties, just a few months before my first visit to Saint Paul, I went to the Broadway opening of August Wilson’s masterwork, Joe Turner’s Come and Gone. The play follows a freed slave named Herald Loomis, who has been captured by a bounty hunter and pressed back into bondage—events, by the way, with historical parallels. Finally liberated, Loomis travels from Tennessee to Pittsburgh in search of the wife from whom he was sundered. In one of the play’s most wrenching moments, Loomis falls to the ground, unable to get back to his feet, haunted by a vision of “bones walking on top of the water,” then sinking to bottom of the sea, then being tossed by a great wave onto the land. There is a conjurer named Bynum living in the same boardinghouse as Loomis, and he completes the image: “Everybody’s standing and walking toward the road . . . They shaking hands and saying goodbye to each other . . . They walking around here now. Mens. Just like you and me. Come right up out of the water.” I understood in that moment that I had witnessed theater at its most transfixing and transformative. I had no idea whatsoever, though, that I had heard August Wilson channeling Ezekiel 37 through the Middle Passage and four centuries of slavery. But August Wilson, who had grown up in church, surely knew these verses:

And He said to me, “Prophesy over these bones and say to them: O dry bones, hear the word of the Lord! Thus said the Lord God to these bones: I will cause breath to enter you and you shall live again. I will lay sinews upon you, and cover you with flesh, and form skin over you. And I will put breath into you, and you shall live again. And you shall know that I am the Lord!”

I prophesied as I had been commanded. And while I was prophesying, suddenly there was a sound of rattling, and the bones came together, bone to matching bone. I looked, and there were sinews on them, and flesh had grown, and skin had formed over them; but there was no breath in them. Then He said to me, “Prophesy to the breath, prophesy, O mortal!” . . . I prophesied as He commanded me. The breath entered them, and they came to life and stood up on their feet, a vast multitude.

Soon enough, though, I would start to learn.

My first glimpse of Saint Paul shattered my expectations. I had envisioned a black church as a storefront operation straight out of the pages of Go Tell It on the Mountain. Saint Paul, to the contrary, had a handsome building of tinted glass and tan bricks, with a sanctuary of soaring cedar beams. The offices had a linked system of desktop computers, a very high-tech arrangement for 1989. The annual budget of nearly $3 million came entirely from the contributions of members. Saint Paul ran everything from a twelve-step program for recovering substance abusers to a rites-of-passage program for teenagers to its own elementary school and credit union. And the revelation for me was that Saint Paul undertook all of these efforts not as forms of public policy or NGO initiative but as acts of doing God’s work. There was no border for its people between secular and sacred.

Reverend Doctor Johnny Ray Youngblood, Saint Paul’s pastor, had taken its pulpit in 1974, when he was twenty-six and fresh out of divinity school and the congregation had dwindled to eighty-two members in a decrepit building in Brownsville. One of Reverend Youngblood’s mentors in ministry had warned him, “You’re going to God’s Alcatraz.” Defying those words, Reverend Youngblood proceeded to build the membership up to five thousand and moved the congregation from Brownsville to a fifteen-year-old former synagogue in East New York.

As I read into the history and theology of the African American church, I came to understand that there were three central biblical texts. One was the Jesus narrative, with Christ interpreted as a radical liberator, a champion of the oppressed. The other two arose from the Hebrew Bible: the Exodus saga, for its obvious parallels to black slavery and emancipation in America, and the social justice prophets, for their fierce critique of the powerful.

For a black minister, Reverend Youngblood was very much a New Testament man. His most penetrating sermons drew upon the Jesus saga. In one that he titled “Christmas in the Raw,” he presented baby Jesus as the child of a teenage mother who can’t explain how she got pregnant—an eloquent way of having Christianity speak to, rather than reject, all the single mothers in a place like East New York. On Easter morning, Reverend Youngblood preached “Lazarus and the Black Man,” in which the resurrection that Jesus performs on Lazarus serves as the metaphor for Christianity uplifting the black men of East New York and Brownsville, so many of them survivors of drug addiction or prison, so many with pasts that made them feel unworthy of church, undeserving of grace.

Yet the prophets also informed Reverend Youngblood’s sensibility. He called Luke 4:18 his mission statement, with its admonition “to preach good news to the poor . . . proclaim freedom for the prisoners and recovery of sight for the blind . . . release the oppressed” [NIV]. That verse was an almost verbatim restatement of Isaiah 61:1–2. Several years before my arrival at Saint Paul, Reverend Youngblood had begun working with community organizers from the Industrial Areas Foundation on a plan to build new housing in East New York and Brownsville, to erect tidy, affordable, owner-occupied row houses on the wrecked terrain of “planned shrinkage.” The program needed a name, and Reverend Youngblood supplied it. These row houses would be called the Nehemiah Homes, a reference to the prophet who urged the ancient Jews, returning from Babylonian exile, to rebuild the shattered walls of Jerusalem.

If Reverend Youngblood ever preached on Ezekiel 37, I do not recall it. But the Book of Ezekiel makes reference to the disgrace and reproach of Jerusalem’s fallen walls, for Ezekiel was also a product of that national calamity. The son of a priestly family, possibly descended from Joshua, Ezekiel was about twenty-five years old when the Babylonians led by Nebuchadnezzar conquered the kingdom of Judah in 597 BCE. During the fifth year of exile, Ezekiel received his vision, to be a “watchman for the house of Israel,” and he issued prophecies over the next twenty-two years.

To be a prophet in the Old Testament/Hebrew Bible was to be, by definition, a dissident, an outsider, a provocateur, a public scold. It was to castigate society during times of security and prosperity and to blame the victims for their iniquity during times of tragedy. The prophets, as Abraham Joshua Heschel put it, were “some of the most disturbing people who have ever lived.” And even by their standards, Ezekiel stuck out as especially eccentric, tilting between periods of illness and paralysis and waves of hallucinatory ecstasy. Drawing on modern psychiatric studies, E. C. Broome diagnosed Ezekiel’s behavior as being “consistent with paranoid schizophrenia.”

Deluded or not, deranged or not, Ezekiel in his vision of dry bones paints an indelible picture of the Jewish people defeated and exiled, their temple in ruins, their national institutions desolated. These are people, God says through Ezekiel, who cry, “Our bones are dried up, our hope is gone; we are doomed” [JPS 37:11]. Uprooted and oppressed, disoriented and powerless, they might as well be skeletons. Yet even though Ezekiel died in 570, thirty-one years before Babylon fell to the Persians and Cyrus allowed the Jews to return, the prophet foresaw redemption, redemption in the form of resurrection. Through Ezekiel’s mouth, God promises, “I am going to open your graves and lift you out of the graves, O my people, and bring you to the land of Israel” [JPS 37:12].

Centuries later, during another Babylonian exile, this one caused by the Roman conquest of Judea and the destruction of the Second Temple, the rabbis of the Talmud debated whether Ezekiel’s vision of the resurrection should be taken as literal or symbolic. On the one hand, Hebrew scripture contains several other direct or implied references to resurrection—by Elijah and Elisha, in the Book of Daniel. On the other hand, by time of the Talmudic era, Christianity had emerged as a distinct religion, and its central, supernatural episode was the resurrection of Jesus. The belief in actual resurrection in real time, not at the End of Days, drew a line between Judaism and Christianity. Over time, Catholic churches came to link Ezekiel 37 to Easter, particularly using it in relation to baptisms conducted on the holy day’s eve. Modern Jews, in contrast, clung to the metaphorical power of the vision. Israel’s national anthem, “Hatikvah,” alludes to Ezekiel 37:11, while inserting one dispositive addition, with its assertion, “Our hope is not yet lost” [emphasis mine].

There is, though, a third way to parse Ezekiel. In the Talmud’s tractate Sanhedrin, as the sages argue reality versus symbol regarding Ezekiel’s vision, Rabbi Judah says, “It was truth; it was a parable.” And I found the truth in his seeming oxymoron at Saint Paul Community Baptist Church.

Long before I got there, long before Reverend Youngblood was born, the exiled Africans of the slavery era had begun appropriating the white-supremacist version of Christianity taught by their masters and transmuting it into what we would now call liberation theology. As the minister and scholar Allen Dwight Callahan has written, “The Bible became the medium through which Africans in North America held on to the precious vestiges of otherwise lost cultural patrimony that survived the protracted slaughter of the Middle Passage.”

For black Americans, there could be no physical return to an intact physical homeland such as the Jews returning from Babylon enjoyed. Despite the founding of Liberia by freed slaves, Marcus Garvey’s back-to-Africa campaign, and the Afrocentricity movement of recent decades, relatively few black Americans have tried to repatriate the way millions of modern Jews have made aliyah to Israel. I vividly remember traveling to Ghana with Reverend Youngblood in late 1990. On our first morning in the capital, Accra, we each had to complete a visitor’s form for a government agency. On the line for nationality, Reverend Youngblood wrote, “African-American.” The clerk ostentatiously crossed out “African.”

Ezekiel’s vision of rebirth, restoration, and resurrection, however, mapped itself exactly onto the African American experience, from the Middle Passage to the Cotton Empire, from the Jim Crow South to the northern ’hood. Ezekiel explained why black people felt like no other Americans, more alienated from the nation’s ideals, or perhaps more attuned to its hypocrisy, than even the most recent planeload of immigrants by choice. Ezekiel also solaced black Americans with the assurance, in Callahan’s phrase, that “the catastrophe of exile did not end Israel’s story.”

This “canonical narrative,” as Henry Louis Gates calls Ezekiel 37, recurs in the spiritual “Dry Bones,” in James Weldon Johnson’s collection of sermonic poems God’s Trombones, in Paul Robeson’s role as a preacher in Oscar Micheaux’s film Body and Soul, and, of course, in August Wilson’s play Joe Turner’s Come and Gone. No expression of Ezekiel in the black idiom may be more resonant than the sermon “Dry Bones in the Valley” by the renowned Reverend C. L. Franklin (who is also known as Aretha’s father). This version, recorded in Detroit in the mid-1950s, conveys the sense of righteous grievance that would explode in that city barely a decade later with the 1967 riot:

You see, a city may be one thing to one people, or a country may mean one thing to one people and altogether another thing to another people. When the white Europeans came to this country, embarked upon these shores, America to them was a land of promise, was a mountaintop of possibilities, was a mountaintop of adventure. But to the Negro, when he embarked upon these shores, America to him was a valley: a valley of slave huts, a valley of slavery and oppression, a valley of sorrows.

It was truth; it was a parable. I saw the truth and the parable when that woman got thrown out of the van and there were no police in sight. I saw the truth and the parable during my time at Saint Paul when two students were shot in the hallways of the neighborhood high school. I saw the truth and the parable when the financial manager of Saint Paul, a supremely dignified man named Rochester Blanks, known to the church’s children as Uncle Rocky, needed to carry a gun for the block-long walk to a bank branch to deposit Sunday’s tithes and offerings.

But all of that served as counterpoint, too, just as C. L. Franklin preached that, even for those in the valley of sorrow, “One of these days the chariot of God will swing low.”

On Easter morning in 1990, the day when Reverend Youngblood delivered his sermon “Lazarus and the Black Man,” the first of three services began at 6:00 A.M. As I drove toward church in the ashen darkness, I caught sight of the high-rise housing project nearby. So many lights were on, so many lights. I had seen those same yellow pinpricks on other early mornings, weekdays, school days, working days. They gave the evidence of people waking up, showering, getting dressed, eating breakfast, and, to put it another way, rising from the grave.

By now, nearly a quarter century has passed since my first trip to Saint Paul. I still visit at least once a year. That is not as often as I’d like, but it is often enough to take note of each new batch of Nehemiah Homes. East New York has its first full-service supermarket in decades, largely through the efforts of the Industrial Areas Foundation. The church operates a charter school. It helps to recruit black applicants for the New York Police Department. The Seventy-Fifth Precinct recorded 18 murders in 2013, compared to 109 in 1990. Personally, I’ve become an observant Jew over the years, and when people ask me how it happened, what’s the secret, I say that I learned how to be a Jew at a black church.

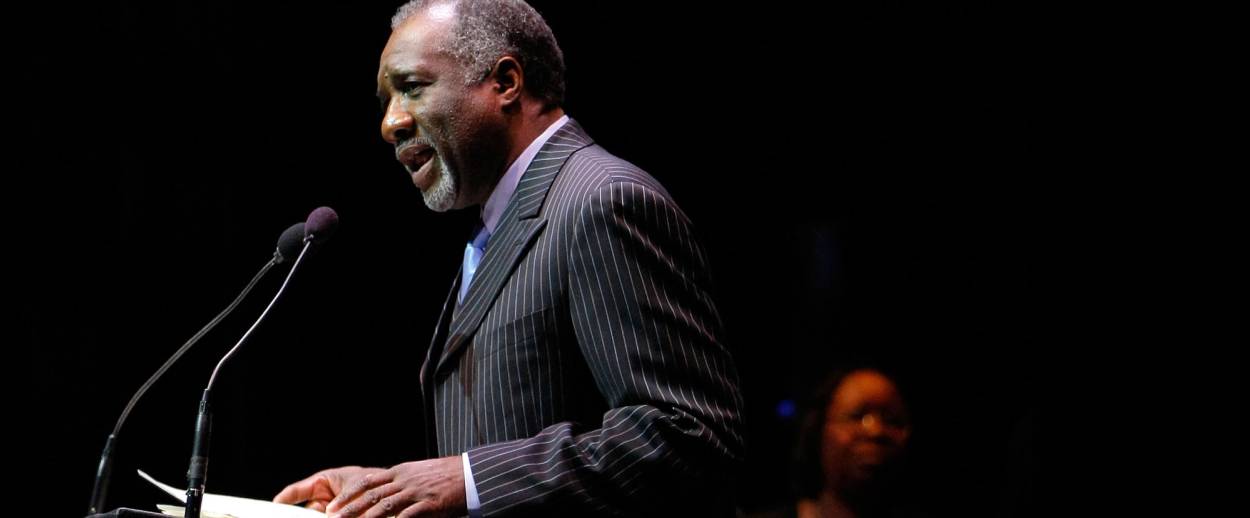

As for Reverend Youngblood, the closest thing to a prophet I’m ever likely to know, he retired from the Saint Paul pulpit in 2009. Back when I first met him, when he was in his early forties, Reverend Youngblood had promised to step down at age sixty, imagining sixty as pretty darn old. Once he got there, though, he didn’t feel so ready for the retirement home he’d bought in Houston. And there was a small, struggling congregation at Mount Pisgah Baptist in Bedford-Stuyvesant that wanted him to become its full-time pastor. So, early in his sixty-first year, he reported to another one of God’s Alcatrazes, which is just another way of saying the Valley of Dry Bones, called once more to prophesy.

Excerpted from The Good Book: Writers Reflect on Favorite Bible Passages, edited by Andrew Blauner, © 2015 by Simon & Schuster.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Samuel G. Freedman is a journalism professor at Columbia University and a regular contributor to Tablet. He also writes the “On Religion” column for The New York Times.