The Yemenite Giant and the Death of Stalin

How the demise of the Soviet dictator changed the history of basketball in Israel and gave my father’s famed jump shot an unexpected role in Cold War politics

One wintry afternoon some years ago, I was in a New York City taxi scrutinizing, as I always do, the name of the cab driver and trying to match a nationality to a name. This particular one was a slam-dunk because of the Russian history class I’d taken in college. The cab driver’s name ended in “—ashvilli,” exactly like Dzugashvilli, the birth name of Josef Stalin. Making comparisons to murderous dictators, however, is not a good conversation opener, even in a New York City cab, so instead I asked, “Are you from Georgia?”

The cab driver was thrilled to have his home country recognized, and we chatted away while hurtling down Seventh Avenue. He told me how he was born in the Republic of Georgia, but that his parents made his way to Israel in the aftermath of WWII.

I made the usual immigrant-connection conversation, telling him that my father was also from Israel. Given the Soviet connection, I threw in the part about how in 1953, my father—then the captain of the Israeli national basketball team—once went to Russia for the European Cup. We had a ways to go down Seventh Avenue, so I relayed my father’s colorful story of his team’s eight-day train ride behind the Iron Curtain, traveling without visas, without even an invitation, hoping they’d be allowed to disembark in Moscow.

The driver slammed the cab into park at the next red light and swung back to look at me through the opening in the plexiglass barrier. The shoulder pad of his worn-out sport coat rose nearly to his ear as he twisted back toward me. “I was on that train,” he said.

*

It was the summer of 1952 and Helsinki was belatedly hosting the Olympic games; its 1940 games had been canceled because of WWII. The 1952 games were notable for the athletic debut of the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China. On a smaller scale, but no less historic, was the participation of the newly formed State of Israel.

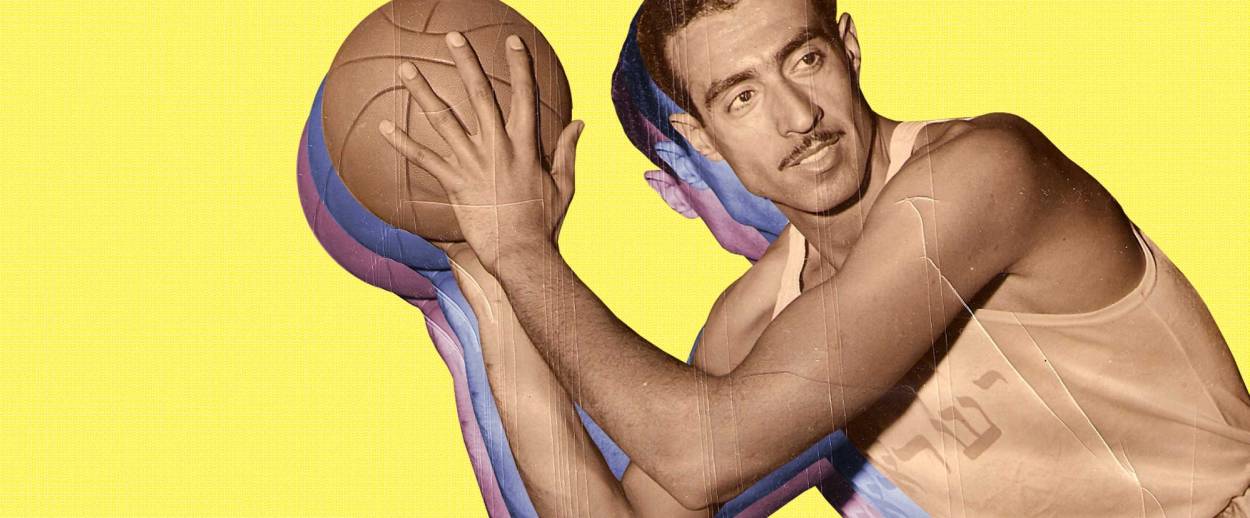

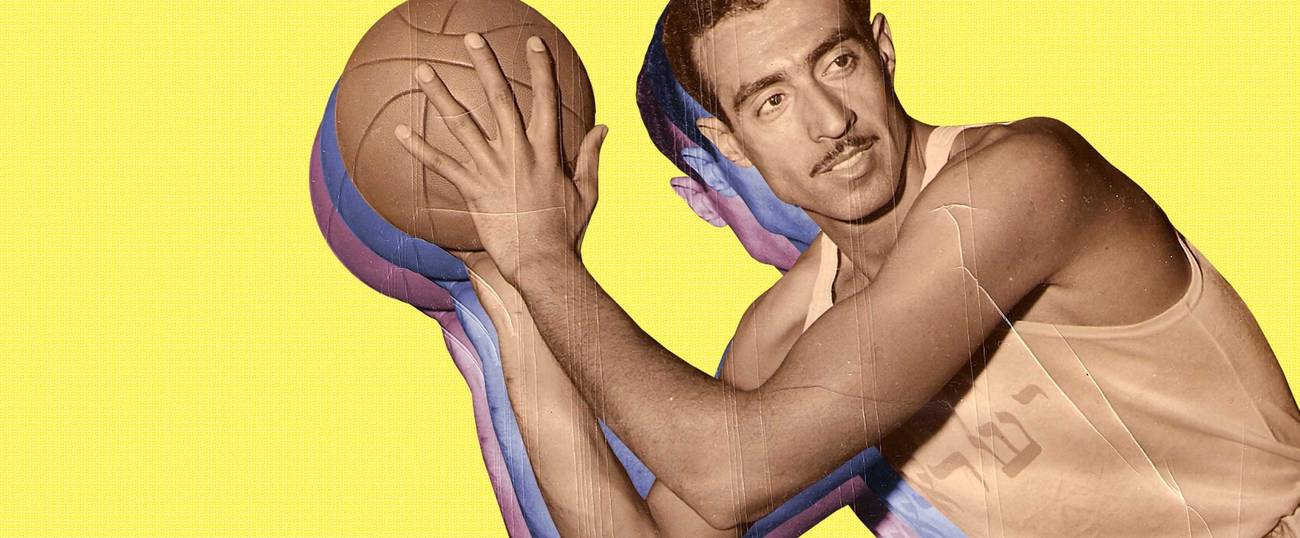

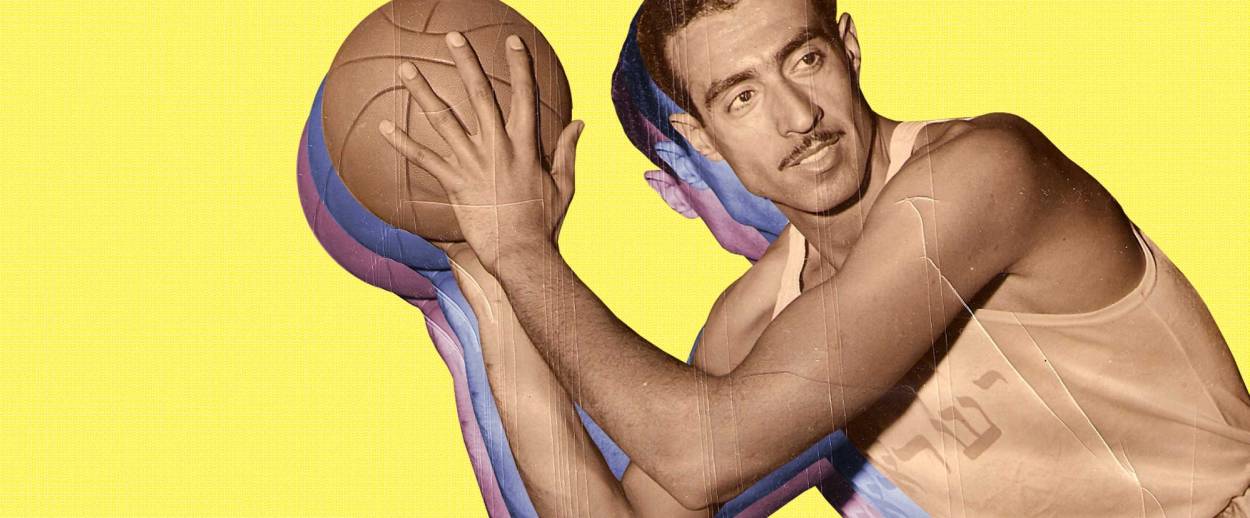

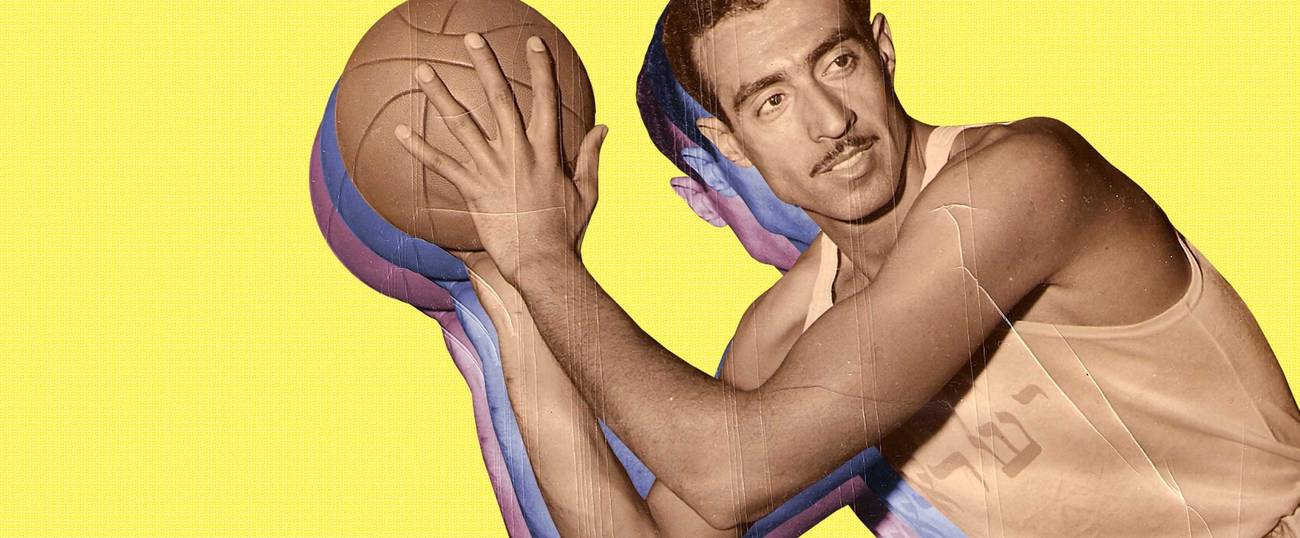

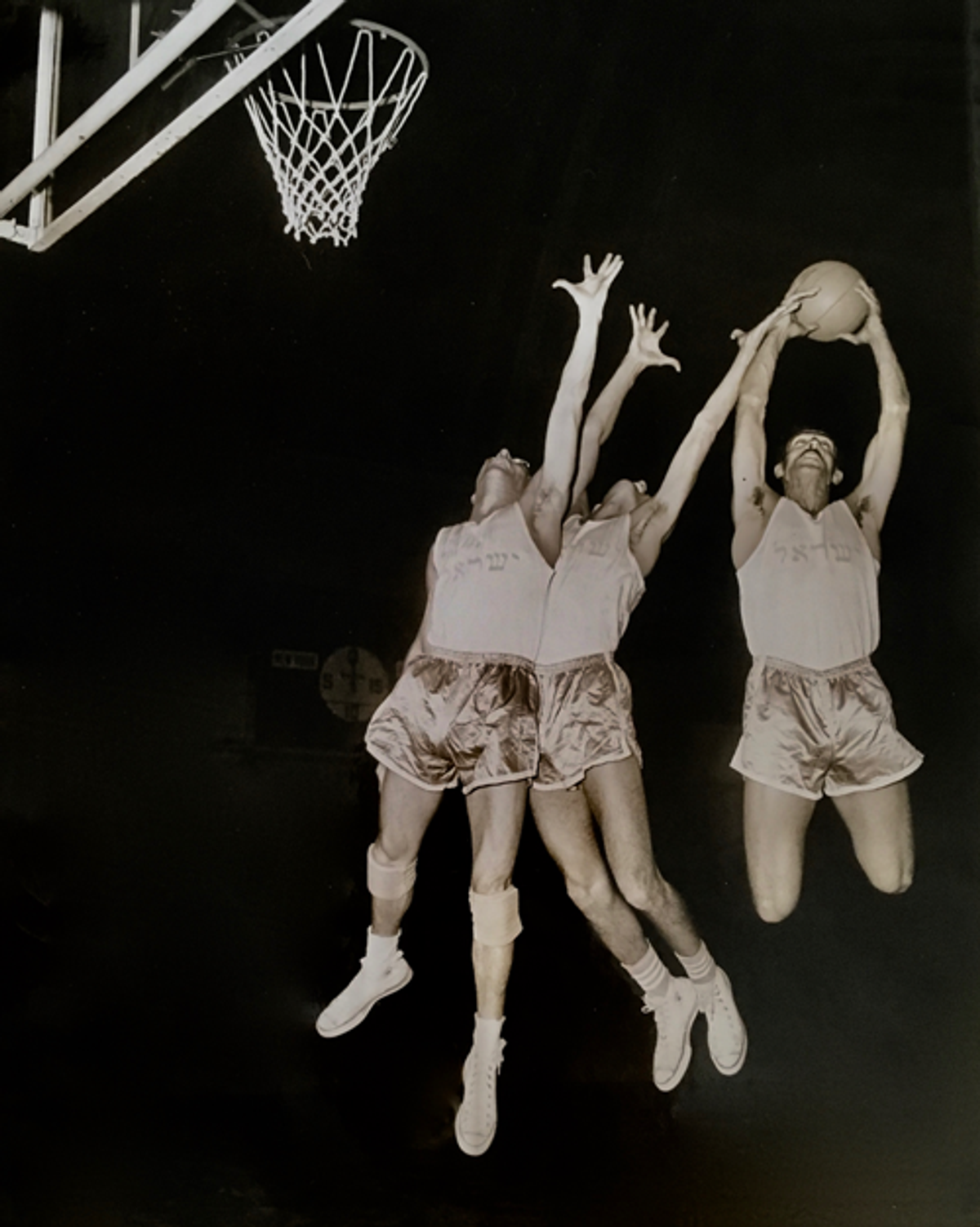

My father, Zacharia Ofri, the 20-year-old son of an immigrant floor layer from Yemen and captain of the Israeli national basketball team, marched with the modest-size delegation into the stadium. It was a heady moment for the young country, even if the athletes’ prowess didn’t quite match the national pride. “We didn’t take home any medals,” my father would later tell me, “but we played!”

As soon as the Olympics finished, the basketball team began preparing for the European Cup to be held in Moscow the following year. Their training ground was a rickety concrete court off Tchernikovsky Street in central Tel Aviv. Sand and stray cats were in abundance, but nets for the basketball hoops were not.

Every institution in fledgling Israel—the symphony orchestra, the army, the Knesset—was an improvised hodgepodge of whatever and whoever was available at the moment. The national basketball team was no different. In addition to my father, the starting string consisted of two other players born in British Palestine—Avram Schneor and Shimon Shelach—plus Marcel Chefetz from Egypt and Ralph Klein from Hungary. At 1.9 meters, my father was the tallest and thus the center and captain. His nickname was Anak Temeni—the Yemenite Giant. (Yemenites were known for many things in those days—savory cuisine, enticing music, lively families—but height was not among them. My father was nearly twice as tall as his parents.)

Hopes for the 1953 Moscow games were high but guarded. The Soviet Union had supported the creation of the Jewish state, though this was motivated mainly by its determination to undermine British influence in the Middle East. The Soviets even facilitated the sale of weapons from Czechoslovakia, which proved decisive in Israel’s War of Independence.

But Stalin’s brutal persecution of Soviet Jews made clear that he was no patron of the Zionist enterprise. His purges, arrests, and deportations kept the gulags well stocked with Jews of all stripes. The year between the Helsinki Olympics and the Moscow games was particularly virulent. Thirteen prominent Yiddish writers were executed in one terrible night in August 1952. On Jan. 13, 1953, the Doctors’ Plot was unleashed, accusing “doctor-poisoners” (most of whom were Jewish) of trying to lay waste to Soviet leadership.

‘We felt impotent. Here we finally had a country, a safe haven, and our Russian brethren could not immigrate.’

Israelis—many of whom had escaped from Russia and still retained families and ties there—led a week of protests in Tel Aviv after the Doctors’ Plot incident. “We felt impotent,” my father recalled. “Here we finally had a country, a safe haven, and our Russian brethren could not immigrate.” The anti-Soviet sentiments ran high at the Tel Aviv protests—Jewish Communists who showed up were met with stones—but it was the right-wing paramilitary group Lehi (the Stern Gang) who wanted blood.

On the evening of Feb. 9, 1953, a Lehi bomb exploded in the Russian Embassy that was housed in an elegant villa on Rothschild Street, 10 blocks from the home my grandfather had built for his family. The Soviet Union, already angry at Israel for its support of the United States during the Korean War and already leaning more strongly toward the Arab nations, promptly severed all diplomatic ties with Israel. An apology from the Israeli government was flatly ignored and the Israeli ambassador was kicked out of the USSR. Prospects for the Yemenite Giant and his team to get to the European Cup in May were looking grim.

Five weeks later, however, Stalin was found urine-soaked and unconscious on the floor of his dacha. Within days, the invincible Man of Steel was dead. Everything—politically, economically, socially, militarily, diplomatically, ethnically, religiously, ideologically and athletically—was suddenly in play again.

For the young government of Israel, which needed to chip away at the Soviets’ full-throated support of the Arab League, Stalin’s death offered an unexpected opening. It decided to pursue a full-court press, in the most literal sense of the term.

In the early hours of a balmy Mediterranean morning, the members of the Israeli National Basketball Team were summoned to the old headquarters of the British police. (It had only been a few years since the British Mandate withdrawal, and the still serviceable building had been repurposed as government offices.) The team members shuffled their feet nervously on the ubiquitous red clay dirt of Tel Aviv.

Then, out of the building marched David Ben-Gurion, his trademark shrubbery of white hair erupting from each side of his scalp. The prime minister was stern and businesslike. Not once did he smile as he paced up and down before the team members. Their mission, he instructed them, was no less than to turn the tide of the Cold War in the Middle East. These young men had just completed their army service and were used to taking orders. But from the prime minister himself!—it was hard not to be awestruck.

“His brusqueness characterized the historical moment,” my father told me. “This was not a time in Israeli history for schmoozing; there was too much work to be done.” Such work was of course easier said than done. Israel had been officially disinvited from the European Cup. Visas to enter Russia could not be had. (On a smaller note, the third week of May also happened to be final exams week at the Teachers College of Wingate Institute, where my father was a first-year student not given to cutting class. He worried about missing the exams, but a professor encouraged him to go. “Russia,” he told my father, “is a once-in-a-lifetime chance.”)

The team was briefed by Foreign Minister Moshe Sharett and assorted government officials. It was stressed that politics was most important; basketball was secondary. “Our mission was to reestablish ties with the Russians,” my father recalled. “If we got in a few rebounds, that would be icing.” The officials wanted them to be noticed by the Russian public—they taught the team traditional Hebrew songs to sing on the bus rides—but also warned them to be careful about what they said and did.

Russian politics aside, there was the internal politics of rival sports clubs to contend with. My father, the team captain, was also captain of the Maccabi Tel Aviv team. The national team had pulled members from both the Maccabi and HaPo’el clubs, whose rivalry at times rose to Cold War levels (and still does today). The balance of power on the national team was eventually settled by appointing a coach from Maccabi but a manager from HaPo’el.

The national team left Israel with no guarantee that they’d be allowed to enter the Soviet Union. Negotiations via the Dutch government were in progress when the team flew to Istanbul. From Turkey, they embarked on a five-day, 1,500-mile train ride through Eastern Europe. After traveling west through Greece and then north through Yugoslavia, they stopped in Sofia, Bulgaria. My father remembered the hotel as dilapidated and dank, but the people friendly and curious. From there, the train rattled along to Romania.

Compared to Sofia, Bucharest exuded a far more tense atmosphere. Nobody on the street would dare talk to a foreigner. Even furtive glances were rare. The train then trudged northeast until it reached the Soviet border (at what is now Moldova) but there was a problem. Although visas to the Soviet Union had been finally negotiated by the Dutch via the Bulgarians, the Russian train tracks turned out to be several inches wider than the Romanian ones.

“We weren’t sure if this was a deliberate action to keep people from crossing the border,” my father remembered, “or just another example of Eastern European incoordination.” Whichever the case, every last passenger was booted out of the train in the remote border town of Iasi. One at a time, each train car was elevated onto blocks while local rail workers painstakingly unscrewed and expanded every set of wheels.

During these idle hours, the Israeli team wandered around Iasi. There wasn’t much to see, but they somehow sniffed out a basketball game on an old clay court. Using hand gestures they explained to the locals that they, too, knew how to play, and somehow a game was negotiated. “It was a friendly game,” my father recalled. With typical modesty he added, “I think we won.”

Finally, all the wheels of all the cars had been widened and the team could reembark. Boarding with them, now, were two new passengers—two Russian “friends” who never left their side for the next 14 days.

It took three more days for the train to reach Moscow, trundling through the boundless Ukraine and southwest expanse of Russia. When at last they finally arrived, the bedraggled team climbed hesitantly out of the train into Moscow’s cavernous Kiyevskaya rail station. Would their Dutch-Bulgarian-Russian visas permit them to enter the country? Would they be allowed to play in the tournament? Would they meet any Russians? Did Ben-Gurion’s gambit stand even a flicker of a chance? Or would they be summarily kicked out like their ambassador and sent packing back through another rambling tour of Eastern Europe?

The bleary-eyed athletes lugged their suitcases into the station and were startled to see cheering crowds amassed before them. Banners were waving. Music was playing. A podium surrounded by flowers had been set up to welcome them.

“We were thrilled,” my father said. “We had accomplished our goal in our first minute in Russia.” Visions of a beaming Ben-Gurion flooded their minds. The head of the Soviet delegation strode over to the Israeli team with bouquets of flowers to distribute. He pumped their hands heartily. “Welcome, welcome,” he said, beaming at them. “We welcome the esteemed Egyptian delegation.”

The Egyptians? There was an awkward pause and then confusion ensued. Arguments and protests were lobbed back and forth like balls at a scrimmage practice. The team, of course, had no idea what was going on since everything was in Russian. But before they could even sniff the flowers, the bouquets were snatched back, the banners ripped down, and the crowds hurried out by their handlers.

‘We just wanted to play ball.’

My father always chuckled when he told this part of the story. The ham-handed ridiculousness of the Cold War chess moves amused him—especially the part about yanking the flowers from their hands. “We just wanted to play ball,” he said.

Hasty arrangements were made and the team was bused off to the Moskva Hotel. The drab eight-story concrete block just off Red Square housed all of the international teams, and the Israeli delegation—along with their two Russian friends—were crammed right in, joining the polyglot chaos that was mealtime in the second-floor cafeteria.

My father was billeted with Ralph Klein in a high-ceilinged room with a corner grate that concealed an obvious microphone. Each time they entered the room, he and Ralph would stand at attention and salute the grate with flourish. “Hakol beseder,” they would announce with military crispness to whomever was listening at the other end. “Todah raba.” (“Everything’s OK. Thank you very much!”)

The Russian minders kept the Israeli athletes constantly on the move. The team remained at the hotel only to eat and sleep, until a bus ferried them off to official sightseeing or to practice. In their two weeks in the Soviet Union, they were permitted exactly one stroll in Red Square. While walking past the cathedrals, an older gentleman on the street noticed the Israeli emblem on their matching blazers and began waving his cane at them, shouting angrily. The players never learned the subject of the tirade because within seconds the Russian chaperones strong-armed the old man and hustled him down an alley.

Each night when the team arrived back at the hotel, they would tally which of their personal possessions were missing. One day it was the toothpaste, another day it was the shaving cream. Each object eventually found its way back to their room the following day, slightly battered but intact.

Moscow didn’t possess a basketball arena. Instead, the games were held in a capacious outdoor soccer stadium. The basketball court was crammed between the soccer goal posts and the track that ran on the perimeter of the stadium. Massive portraits of Lenin and Stalin loomed over everyone. Below the Soviet icons were the words, “Peace Between Nations.” I don’t know if anyone had translated this irony to the Israeli team.

On May 24, 1953, the Yemenite Giant tipped off the ball to initiate the Israelis into the European championship. His team routed the Finns: 60-36. The next day they beat the Bulgarians, 61-48. They ran head-to-head with the Hungarians, then beat the Czechs, the Italians, and the Yugoslavians. But they lost to France and to Hungary, and were creamed by the Soviets, 75-25, on June 3. (The Egyptians and the Lebanese refused to play against them because of the Arab League boycott, so those games were forfeited to the Israelis.)

It was an exhilarating outcome, both politically and athletically.

The Soviets ultimately won the European Cup, but the Israelis came in a respectable fifth out of 17 teams competing. Relations with the Soviet Union began to thaw after the games, and diplomatic ties were restored by the end of July. For my father and his teammates—new to competition, new to statehood, new to the international scene—it was an exhilarating outcome, both politically and athletically. Now they were free to start preparing for their next goal: the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne.

*

The Sinai desert—for generations a sleepy region of Bedouin tribes—had gained new political, economic, and military value ever since the digging of the Suez Canal. Egypt had choked off Israel’s southern port of Eilat with a naval blockade and was steadily building up its military, thanks to Soviet-facilitated arms sales from Czechoslovakia. Its fedayeen were conducting ever more aggressive cross-border raids into southern Israel, targeting civilians in addition to military targets.

Moshe Dayan’s heavy-handed counterattacks had become both a drain on Israeli resources and a source of international condemnation. The tension ratcheted up on July 26, 1956, when Gamal Abdel Nasser forcibly nationalized the Suez Canal Company, elbowing out the British and French who had controlled the vital canal until then. War was percolating in the air.

Had the 1956 summer Olympic games been held in the Northern Hemisphere that year, my father and his teammates would likely have attended. They probably would have been midway through the games when Nasser rattled the world with his aggressive move. But because of the choice of Australia, the summer games wouldn’t be held until late November that year—summer in the Southern Hemisphere.

On Oct. 29, 1956, however, Israel invaded the Sinai Peninsula, determined to remove the Egyptian threat once and for all. It was its first offensive war—equally controversial in Israeli kitchens and in international forums. But Dayan had rallied the backing of the British and especially of the French, who were livid about Egypt’s support of the Algerian rebels. He was determined to cut Nasser down.

Israel was a tiny country at the time, and its standing army was not sufficient to take on the Soviet-supported Egyptian forces. Operation Kadesh, as it was called, would require every available hand on deck—and fast. In 72 hours, the army mobilized 100,000 reservists into active duty. Every available hand, of course, included the Melbourne-bound basketball team.

As wars go, this one was fast and furious, at least for the actual fighting. Israel’s tanks routed the Egyptian forces in six days, confirming the country’s bet on armored divisions as well as its bet on reserve troops as the basis for Israel’s military power. By Nov. 5 the fighting was over. But international negotiations to end the hostilities took months. The Israeli forces didn’t withdraw until March 1957. The Olympic window had closed.

My father never spoke much about what must have been a crushing disappointment to a 25-year-old athlete at the peak of his abilities. He never once expressed resentment toward his country that somehow couldn’t spare even five of those 100,000 reservists to represent it at the Melbourne Olympics.

The only take-home lesson of that era that my father conveyed to me was the one-canteen rule. During those months of deployment in the Sinai desert, each soldier was issued exactly one canteen of water per day. That was your water for drinking, cooking, washing, shaving, and brushing teeth. You didn’t waste one single drop, much less five. For Israel and its canteen of reserve soldiers, the philosophy was evidently the same.

But the young country did ultimately recognize that missing an Olympics is a significant and likely irreplaceable event. Waiting four years till the next one is not practical or even possible for most athletes. So as a compensation for missing the games, a tour of exhibition games was arranged for the Israeli national basketball team. My father and his team donned matching pea coats and set off to see snow for the first time in Boston and to pose in front of the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco. But it was New York City that caught his eye.

Conveniently enough, New York University at that time sported a Division One NCAA team. They offered him a basketball scholarship (and a soccer scholarship while they were at it) and my father took his place with the NYU Violets for the 1957-58 season. The Yemenite Giant was now the shortest player on the team, of course, but that didn’t matter. The NYU team didn’t make it into the NCAA playoffs that year, but that also didn’t matter. An injury took him out of the following season, but that didn’t matter either.

The Yemenite Giant was now the shortest player on the team.

He’d discovered how much he loved mathematics and education, and completed his degree at NYU. He discovered how much he enjoyed the English language and how enticing The New York Times crossword puzzles could be, even for a foreigner who forever mixed up strip, strap, and stripe. He also discovered the American college students who hung out at Washington Square Park. He married one—my mother—and they subsisted on the cheese sandwiches at Chock full o’Nuts until they graduated from NYU.

They raised a family in New York, but his heart always remained in Israel. After my brother and I were safely tucked away in college, my parents moved to Israel. My father had formally retired from teaching, but he coached basketball into his early 80s. Everywhere he went, somebody recognized him—whether it was in the shuk behind his childhood home or a random walk down Dizengoff Street.

For men of a certain age—invariably accompanied by a belly of a certain heft—Israel in its young days was an intimate, haimish experience. Everyone knew everyone, and everyone knew Zacharia Ofri (who remained rail thin his entire life due to his abstemious diet). Everyone knew that he was the first player in the Holy Land to dunk a basketball. Everyone knew about the time a HaPo’el team refused to play, citing the unfair height advantage of the Maccabi Tel Aviv captain. Everyone knew about the 1953 trip to Moscow.

When he passed away in 2018, the proceedings were characteristically Israeli. The attendees at the funeral dressed in casual clothes, many in jeans. The service was simple and unadorned—no casket, no beautifying of death with embalmment. Just a tallis covering his long, lanky body as he was lowered deep into the red clay soil under a brilliant Israeli sun. The funeral was followed by the first evening of shiva. And after the shiva … a basketball game.

It obviously hadn’t been planned this way, but it so happened that on the night of that my father was laid to rest, Maccabi Tel Aviv was playing its forever archrival, HaPo’el Yerushalayim. And that is how I found myself in the Menora Mivtachim arena in south Tel Aviv on the evening of my father’s funeral, along with 10,000 fanatical HaPo’el and Maccabi fans.

It’s surprising how few professional basketball games I’ve attended in my life, given my father’s history. I’ve enjoyed playing the game (and don’t mind adding here that the McGill University women’s physiology basketball team won the intramural cup the year I was captain) but I’d never been a sports fan who would attend professional games. So it was a somewhat new experience to be in a sea of shouting fans, squinting to follow the peregrinations of a small orange ball.

It was admittedly a bit disorienting, as I was exhausted and teary-eyed, with mud still caked on my shoes from the cemetery. It was hard not to keep fingering the tear in my sweater from the funeral, marking the start of our seven-day period of mourning.

Suddenly, on the Jumbotron came a picture of Zacharia Ofri spinning the ball on his index finger. (His ball handling had earned him a second nickname of Ta-tum, after Goose Tatum of the Harlem Globetrotters.) Tall, lean, and buff—there was the 25-year-old version of my father on the screen.

This was my father, whom I’d really only known as an unassuming high school math teacher who supplemented his income by tutoring neighborhood kids for their bar mitzvahs. My father, whose knowledge of Torah was so vast that he could offer up practically any portion from memory and chant it in Sephardic, Yemenite, or Ashkenazi flavor. My father, who still wore the Lands’ End cable sweater I’d bought on sale for his birthday two decades earlier. My father who relished mathematical coincidences of a diner bill matching a birth date, or title of the weekly Torah portion rhyming with the name tag of the waiter at said diner. My father who applied the one-canteen rule to his entire life, washing dishes with the drip-irrigation method that Israel famously used to cultivate its desert and its soldiers.

I could feel my own heart swell for my father. In his quiet manner, he had served his country honorably—athletically, politically, militarily.

As the swell of thousands of voices singing “Hatikvah” rang through the stadium, I could feel my own heart swell for my father. In his quiet manner, he had served his country honorably—athletically, politically, militarily. It still seemed improbable to think how his basketball career and ultimately his life was shaped by Stalin’s death and Nasser’s miscalculation. But without the twists of fate provided by these autocrats, I wouldn’t have ended up in New York. And I wouldn’t have ended up in that cab with the driver who’d been on the train with my father.

On the rest of the ride back to my apartment, that cab driver told me how he’d been a fervent Maccabi Tel Aviv fan as a kid. A groupie, he told me. As a teenager, he pestered them into allowing him to be a ball boy at their practices. And when the command from Ben-Gurion came to head to Moscow, he talked himself onto that train.

It’s a small world—yes, we all know that—but this coincidence seemed staggering to me. A random taxi ride in a city of 8 million and suddenly we were back on the Romanian border, each train car getting its wheels painstakingly widened. The driver remembered my father well. “The Yemenite Giant,” he said, the jowls framing his moon-shaped face bristling with unshaven beard. “Ta-tum!”

And then we arrived at West 15th Street. I zipped my coat, gathered my things, making sure I had both of my gloves. When the driver pulled away I realized I’d forgotten to write down his name. All I remembered was that it rhymed with Stalin’s. It was the kind of coincidence my father relished.

Danielle Ofri is a physician in New York City and author of When We Do Harm: A Doctor Confronts Medical Error.