A Time to Die

Talking to my kids about death, with a little help from a lamb

My 4-year-old daughter Shuli recently asked me how old I was. We were behind our apartment building with her brother Yosef, killing time on a Sunday afternoon. I told her that I was 33 years old. After a moment, she said, “When Yosef is 33, you’re going to die.”

My kids often speculate on the exact timing of my demise. They know that people die when they’re old, as their great-grandfather did last summer. But what counts as “old”? I’m a grown-up, so I’m at least a little old. When Yosef is 33, I’ll be a lot old. That’s when Shuli thinks that I’ll drop dead, maybe even on the day he turns 33 itself, at his birthday party.

Thankfully, Yosef, who is beginning first grade, came to my rescue. “Daddy won’t die when I’m 33,” he said. He offered a mathematical justification: When he’s 33, I’ll be 60. But, he argued, people don’t die until they are around 100. “Daddy won’t be dead for 40 more years after I’m 33,” he said with complete confidence.

Shuli seemed indifferent, the numbers involved being more or less the same to her.

This felt like it could be a teachable moment for my children, but I froze up. What do kids need to learn about death, anyway? Later, worried about my nonresponse, I went searching through my own childhood experiences for perspective.

There are three events that dominate my own young memories of death. The first was reading Bridge to Terabithia, the YA novel by Katherine Paterson. I was in second grade. I don’t remember what Terabithia is or what sort of bridges were involved but I do remember a child’s sudden death, and no, thank you, I’m not at all eager to revisit the book after all these years. I believe Bridge to Terabithia was the first book that made me cry, and boy did it ever. I grieved in silence, alone in my room.

The second event happened years later, when I was 14. A friend’s older brother was a youth group leader with an enormous personality. He died in a car crash while working at summer camp. In the bathroom at the memorial service, I saw a boy who had been a bully to me, staring into a mirror. His eyes were pink and he sobbed in tightly controlled bursts. This was the “first death” for many of us.

The third event is a bit harder to explain, but it happened a year later and was an officially sanctioned event at my Orthodox yeshiva high school. This was in June 2003 when Daf Yomi, the Talmud study cycle, began studying Kodshim. This fifth section of the Talmud is largely concerned with sacrifice and kosher slaughter. In honor of this enterprise a sponsor had arranged for demonstrations of shechita—that is, kosher slaughter—across the Chicagoland area.

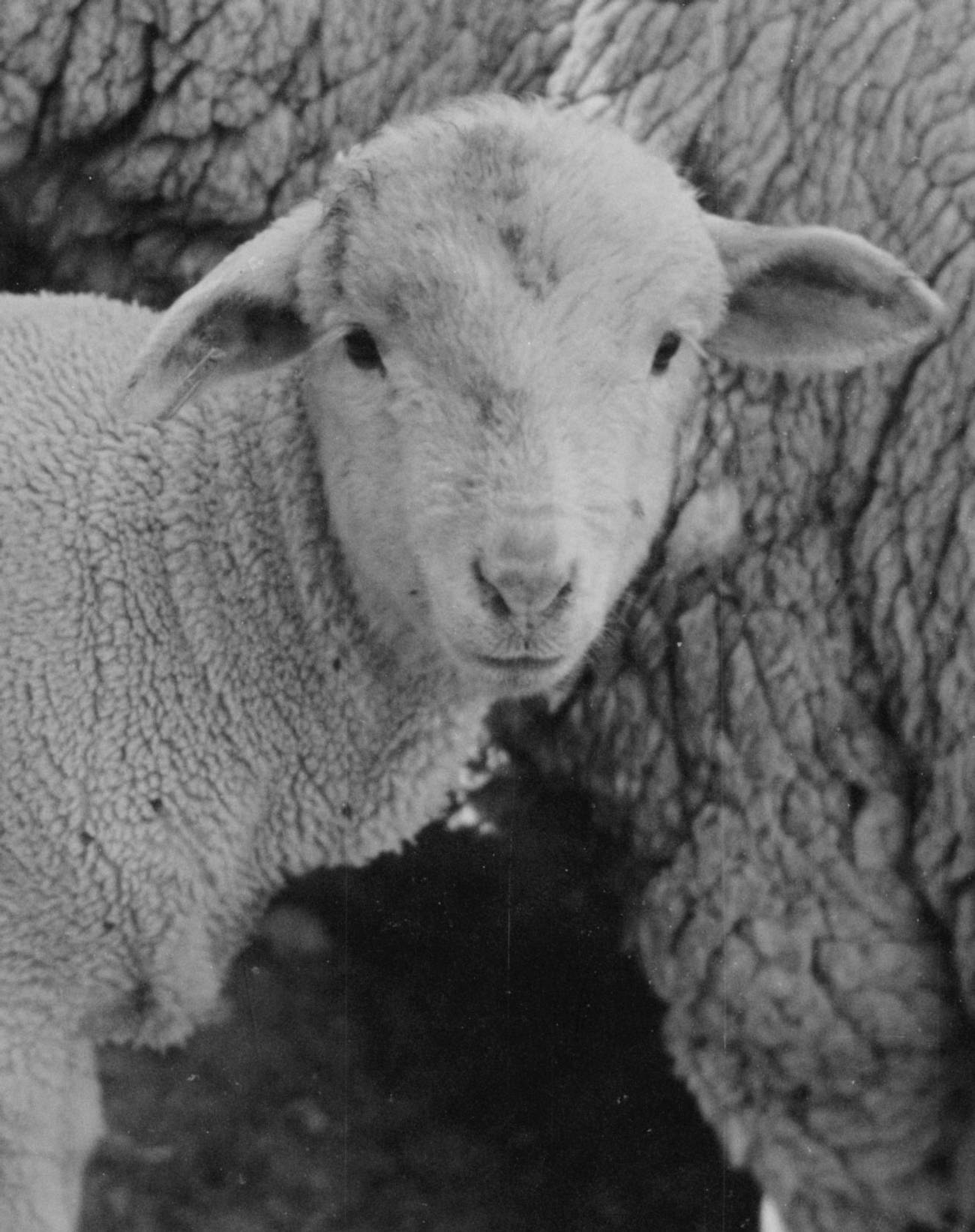

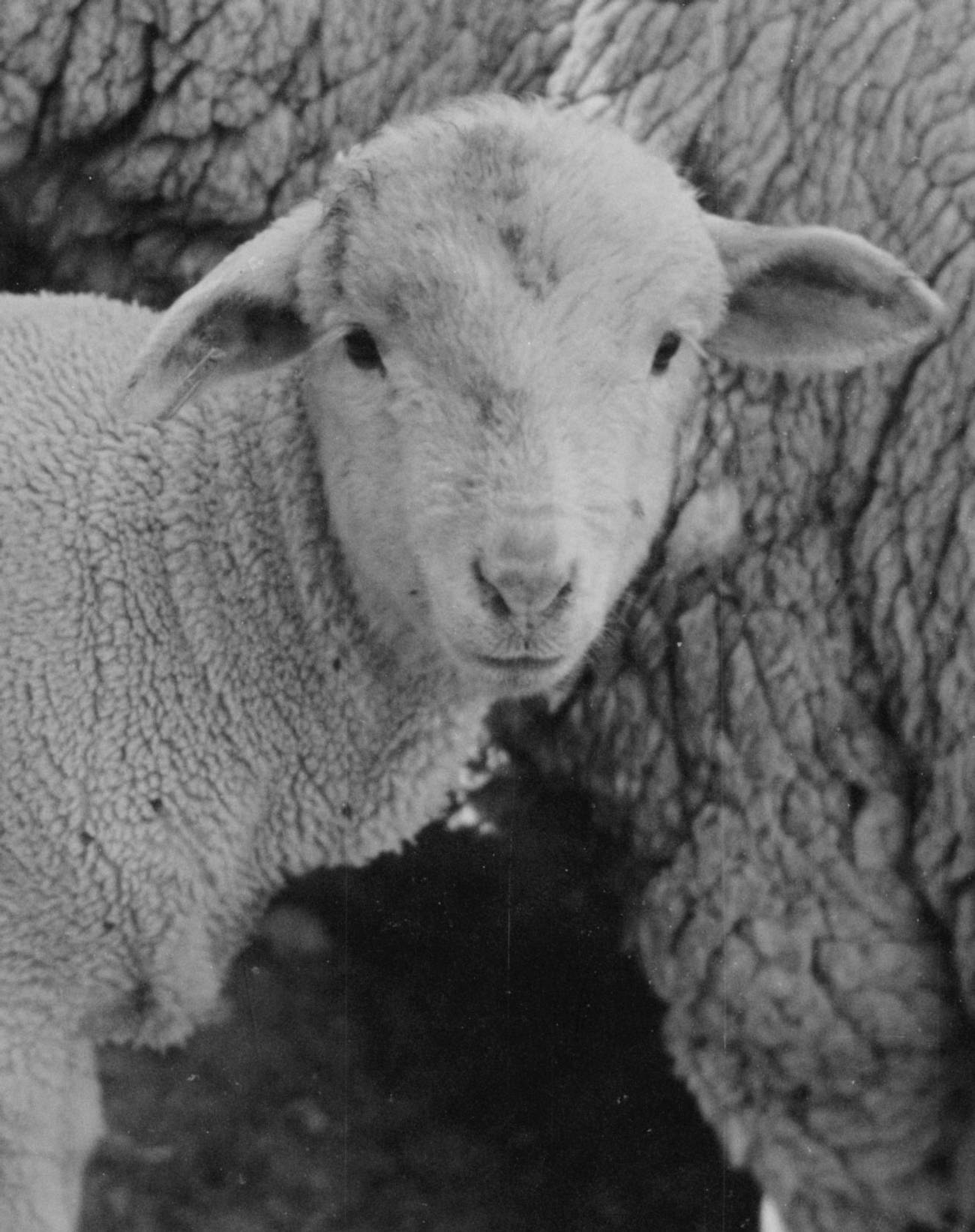

There would be a lamb. There would be a shochet. He would have an extremely sharp knife. All were invited to join in the school parking lot after lunch.

My high school was shaped like an “H,” with parking spaces inside the concavities. The lot was surrounded by three floors of classrooms, dormitories, and offices. The classrooms and dorms above had been transformed into box seats, with teenage heads poking out of each opening. Down at ground level the shochet had tied his lamb to a stake and laid down a blue tarp. In front of the tarp, a crowd gathered several rows deep. That’s where I stood.

The shochet was a young man with a black beard. He wore a white shirt, and though I don’t remember this he absolutely must have had some sort of smock. He spent quite some time sharpening his blade as the crowd gathered. He soon explained that shechita requires an absolutely smooth blade, no bends or nicks allowed, any of which could invalidate the slaughter and render the animal treyf.

Interrupting, constantly, was the lamb, whose baas were loud and growing more frequent.

The crowd was all men and boys. Many of my rabbis were present. Many of the adult students lived on campus in those rooms above the parking lot, and their young children watched out the windows. Rabbi K., my freshman year rebbe, had his toddler son on his shoulders. He wasn’t the only father who had brought his child to watch the shechita, but he was probably the only one working so hard to get his kid a good view.

The shochet spent what seemed like forever explaining things. He was soft-spoken and I couldn’t hear a word. Sometimes I would catch a phrase and think I was following the gist. But then the lamb would interrupt—baa—and I’d lose it. I moved restlessly in place, trying to make sure I didn’t miss the moment of truth.

And then, just like that, it was over. He killed it. One, two, three, finished. That was it. The baaing stopped. There was much less blood than I had expected.

But this was just the start. The shochet had more to do and explain. There are many ways for an animal to be declared treyf, he said, and he would have to check to make sure none of them applied. Meanwhile, the lamb lay on the tarp. The young shochet took a step toward the crowd to describe what came next.

Then the lamb jumped into the air.

There was an audible gasp and the whole crowd took one huge step away from the tarp. I couldn’t tell you how high the lamb went. In my memory it was about a foot in the air, though it might have been only a few inches. It doesn’t matter, height wasn’t the point. This little lamb wasn’t quite finished.

The shochet seemed slightly annoyed by our reaction. He explained that this was normal. Often animals, in the throes of death, continue to twitch and spasm. Something about their nervous systems, or whatever. As the shochet lectured, the animal (its corpse?) jolted up again.

Was he right—was this normal? Or had he botched the job, and was now coolly trying to cover it up?

Was the lamb still alive?

The shochet continued to talk. A few words later, there was another big twitch. Now he fully ignored it, expecting us to do the same. He went on about how to butcher the body and check for treyfot.

Eventually, the lamb settled into its death.

Up above, dormitory windows slammed shut. Down below the crowd dissipated. The show was over.

Looking back, the entire episode raises questions for me. Was it (a) appropriate, (b) educational, or (c) ethical for a high school to host a public shechita? I don’t know if we’d all agree on the answers. My own: maybe, very, and probably not.

What I really find myself thinking about is what it meant to be part of that crowd, watching the slaughter. A crowd is a kind of social machine, for good or for ill. We watch the people around us and learn from them whether what we’re experiencing is normal, and hence tolerable. It’s one thing to experience something potentially traumatic, and something else entirely to experience it with other people.

For example, a friend of mine who was present at the shechita remembers being surprised that evening by a lamb dinner. He told me that, while disgusted at first, he was proud to say he polished off his plate. Now, that’s an interesting lesson learned from watching a lamb get whacked. But it speaks to the power of experiencing death with other people, something I have only realized while thinking about my own children and their needs.

I notice that my daughter didn’t ask, “When are you going to die?” Instead she made a declaration—and on this day you shall perish—and watched for my reaction. Thinking of me not as a parent but just as a fellow human, what would I do? Would I scream? Cry? Cut off the discussion and refuse to engage? And at times this seems like an important parental role: to be the closest nearby person, someone your kids can provoke to see what beliefs, attitudes, and reactions come out.

Once you get the basic facts of life’s end, as we all eventually do, there is one thing and one thing only to learn about death: how to live with it. In those conversations with my children, they probably don’t need me to clarify any facts. Instead, they need me to help form something like the crowd that surrounded the shechita. This is true even if the corpse under discussion happens to be my own.

A few weeks ago, my son and daughter were again behind our building, this time running with a gang of children. One member of the child horde saw something and stopped the others. Soon they had gathered around what turned out to be a dead squirrel. It had died recently, or at least it had barely started to decay. The kids debated whether it was really dead or not.

Of course, one kid had the bright idea to get a stick.

I was drafted by a group of parents to go over and handle the situation. I fell into the children’s ranks. A few flies buzzed over the squirrel’s body. It didn’t look like it was sleeping—do squirrels sleep on their backs, paws directly in the air?

“Leave it alone guys, it’s dead,” I said.

“We’re going to poke it with a stick,” said the kid with the stick.

While I eventually did chase the kids away, citing disease, I noticed myself moving more slowly than I might have. Nobody poked it, but those kids got some quality time with that squirrel. Even as I went to send them away, there was some part of me that thought I shouldn’t be so quick to get in the way of this, a group of people standing together and discussing a corpse.

Michael Pershan is a math teacher and writer living in New York City. He is the author of Teaching Math With Examples.