Tiny Temples

How models of Jerusalem’s holy sites became tourist attractions around the world

For millennia, those eager to picture the First or Second Temple in Jerusalem had to rely on their imagination. While there was no shortage of rituals lamenting the destruction of the sacred site or prayers for its restoration, visual depictions were something else again.

By the early Middle Ages, images of the Temple’s implements and of its physical layout, inspired by scriptural and related references, graced a number of manuscripts, among them Maimonides’ Mishneh Torah. But households that owned a copy of any of these handwritten texts were far and few between.

With the advent in the 19th century, if not earlier, of modern technologies of publication, circulation, and travel, the prospect of visualizing the ancient Temple as an actual, knowable, physical construct situated in an actual, knowable landscape became more and more attainable. From drawings to photographs, images of the so-called biblical lands—the built and natural environments as well as their seemingly timeless inhabitants—increasingly accompanied new editions of the Bible.

They also appeared in freestanding compilations such as Felix Bonfils’ Souvenirs d’Orient of 1878, which boasted of its in situ photographs of the ancient Near East and its “cortege of splendors.” Readers could “esteem themselves happy” simply by gazing upon these “prestigious pictures,” noted the volume’s foreword approvingly, adding that the effect of “illusion is complete so that one believes himself to be actually in the presence of the subject.”

Magic lantern slides, also known as stereopticon slides, furthered that illusion. The device used to project them, which was called a stereoscope, provided a “window through which to walk … and see objects and places in natural size and at a natural distance.” To bring home the veracity of the biblical narrative, Sunday-school teachers and religiously minded parents could choose from among hundreds of images, bundled together and advertised via promotional brochures, of biblical sites, ancient Temple ruins, and “costume studies” of locals in their native dress.

Meanwhile, those who had the economic means and physical stamina to undertake a lengthy and often demanding voyage to the Near East could rely on a growing genre of illustrated travel literature to whet their appetite for adventure and direct their steps. Baedeker’s 1876 Palestine and Syria: Handbook for Travellers was among the earliest of such guidebooks, whose lengthy, detailed description of the route one might take from, say, Jaffa to Jerusalem, came in handy, as did its helpful hints on matters ranging from how much to pack (very little); what to look for when securing a horse, mule, or donkey (make sure they were “not addicted to lying down and rolling”); and how to come by the local currency (“be very cautious” when dealing with “money-changers, generally Jews”). Its maps, photographs, and other visual devices were also among its most desirable features for they could be trusted, it was said, where “information sought from natives” could not.

Even so, nothing brought interested parties closer to the Holy Land and, most especially, to ancient Jerusalem, than three-dimensional, scale models of its venerated holy sites such as King Solomon’s Temple, the Temple Mount, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, and Rachel’s Tomb. Fashioned out of wood or plaster, putty or bronze, exhibited at world’s fairs and sold at pilgrimage sites and tourist shops, these objects became increasingly popular throughout the 19th century.

It’s not hard to understand their appeal. Where drawings and photographs were flat, three-dimensional models allowed for greater precision and with it, a heightened attentiveness to detail. Scale, too, had much to with their winning over attentive audiences. By cutting down to size and miniaturizing places that loomed so very large in the religious and cultural history of the West, the models placed the past within reach, rendering it accessible.

What’s more, at a time when both archaeology and Zionism were coming into their own and, for better or worse, were joined at the hip, physical evocations of Jerusalem’s holy sites did double duty, serving as the visual and material equivalent of a proof text. For archaeologists of the Holy Land, these reconstructions aided and abetted their scientific inquiries; for Zionists, they grounded the movement’s aspirations in something far more real, more tangible, than tradition or emotion.

When touring contemporary Jerusalem, many of us might have seen a model of its first-century antecedents that was situated on the grounds of the Holy Land Hotel. Painstakingly created in the 1960s by Michael Avi-Yonah of Israel’s Department of Antiquities and rendered out of Jerusalem stone and marble, the 22,000-square-foot reconstruction of the Second Temple and its surroundings was relocated in 2006 to the Israel Museum where, fittingly enough, it now sits between the Billy Rose Sculpture Garden and the Shrine of the Book, nodding to both.

A popular tourist attraction, this latter-day model was preceded almost 100 years earlier by painted wooden reconstructions of the ancient Temples and the Temple Mount fashioned in the 1870s and 1880s by Conrad Schick, a German Lutheran missionary-cum-craftsman who had settled in Jerusalem several decades before. Making use of movable parts, hinges and hooks, layers and lids, and built to travel, his clever constructions, or what Schick himself liked to call “plastic reproductions of the known,” enabled the mind to visualize the imprint of the past on the present and to encounter the ways in which Jerusalem’s history was, quite literally, a layered affair.

Nothing brought interested parties closer to the Holy Land and, most especially, to ancient Jerusalem, than three-dimensional, scale models of its venerated holy sites.

He made it look easy, effectively resolving the difficulties inherent in the process of translating textual references into physical form which measured, in some grand cases, as long as 18 feet, nearly 6 feet wide and 20 inches high. The challenges that would have “staggered any ordinary man were simply a stimulus to him,” observed one of the model maker’s many champions, adding that “each step, each window and door, had chapter and verse to justify its existence.”

As fascinating, and determined, a personality as his “masterly” creations, Schick typified the larger-than-life characters who peopled Jerusalem during the closing years of the 19th century. A self-styled and self-taught archaeologist and architect, whose excavations of Jerusalem’s topography figured in hundreds of articles for the Palestine Exploration Fund, he also designed the neighborhood of Mea Shearim from the ground up and built several structures outside the Old City walls such as the German Hospital in downtown Jerusalem, now known as Bikkur Holim, and Hansen’s Hospital (originally named the Jesus Hilfe Asyl) in the Talbieh section of town, both of which still stand.

Renowned for his geniality and hospitality, for inviting visitors to his home to see some of his reconstructions, Schick “was never more delighted than when exhibiting his model to Jews,” related the American Israelite shortly after his demise in 1901. “No Jewish pilgrim of the past quarter of a century but has a story to tell of Dr. Schick’s courtesy and kindness.”

Those fortunate enough to encounter his handiwork were quite taken by its “magic,” and for good reason. When looking at a model of Haram al-Sharif, for instance, what swam immediately into view were two beautifully detailed, miniature versions of the Dome of the Rock and the Al-Aqsa Mosque, both of which could be detached from their setting and moved about like chess pieces. Were you then to lift up the platform on which these Muslim holy sites rested, King Solomon’s Temple and its adjacent rock formations filled the eye. In other iterations, Herod’s Temple nestled atop King Solomon’s, and in still others, while both temples shared a common foundation they were meant to be exhibited independently of one another.

Schick’s “ingenious” designs won him many fans, and prizes, too, including his successful entry to a competition that brought a free-standing model of the Dome of the Rock to the Vienna World’s Fair in 1873, where it was one of the star attractions of the Ottoman Pavilion. Decades later, in 1904, several renditions of the Temple traveled to the St. Louis World’s Fair where thousands of Americans had the opportunity to see for themselves what all the fuss was about.

New World residents who didn’t make it to St. Louis could make a beeline instead for Boston and Harvard University’s Semitic Museum, whose curator, David G. Lyon, purchased several of Schick’s models from his family and exhibited them on the museum’s third floor, in its “Palestinian room.” There they stood for over 50 years until de-accessioned and, presumably, discarded. (Today they might have enjoyed a different fate, valued—and salvaged—as historical artifacts, indices of the state of the field at the time they were made, but that’s a story for another time.)

Fortunately, some of Schick’s late-19th-century maquettes have managed to survive into the 21st and are currently on view at Jerusalem’s Christ Church Heritage Center. In his day, the facility was known as the “House of Industry,” where converts to Christianity were instructed in craftwork as well as catechism. This site also happens to be where Schick’s workshop was located, the birthplace of his creations.

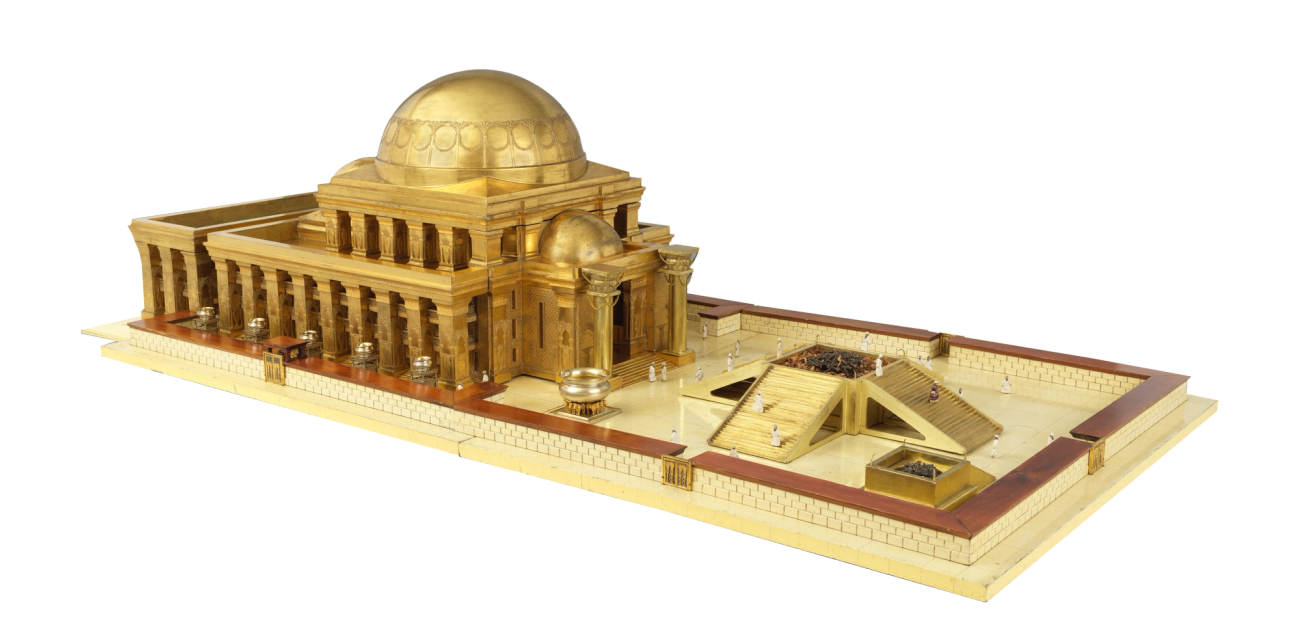

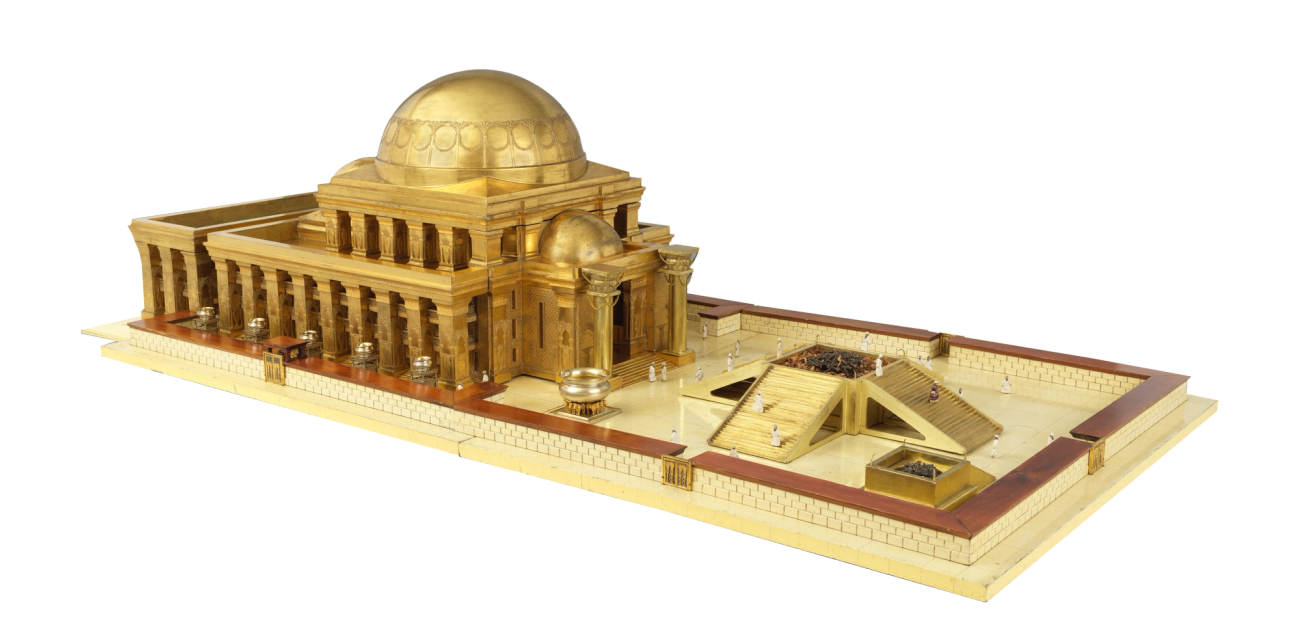

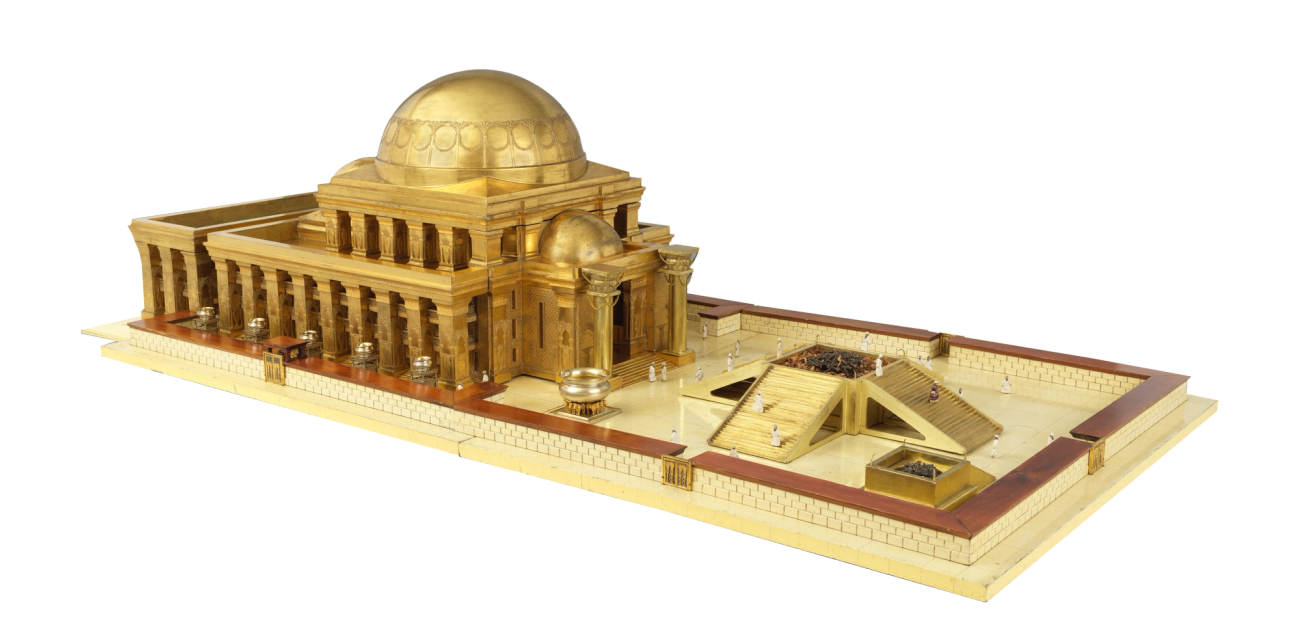

In 1887, amid the glorious setting of London’s Royal Albert Hall, and under the imprimatur of the Anglo-Jewish Historical Exhibition, a “remarkable reconstruction” of King Solomon’s Temple, created only a few years earlier out of gilded wood, silver, bronze, and papier-mache, and measuring the size of a baronial dining room table, took center stage. “Nothing,” prospective visitors were told, “will catch the eye and occupy the mind more.”

Designed by Thomas Newberry, a lifelong student of the Bible, author of the “Englishman’s Bible,” and a frequent lecturer on the history of the Temple, and executed over the course of three years by the London firm of William Bartlett & Co., “carvers, gilders, decorators and restorers of works of art and vertu,” this marvelously detailed, gleaming rendition of the Temple’s architecture, its setting, and its vessels enabled visitors to “gain some conception of the magnificence and splendor” of the ancient complex. To gild the lily, a cluster of tiny figurines clothed in ancient dress were positioned about the complex, adding a human dimension.

Strikingly beautiful in its own right, the Temple model also captured in one fell swoop the exhibition’s ambitious objectives: to awaken British Jewry to its cultural patrimony; stoke a stronger, more palpable, sense of history; and demonstrate the existence of an aesthetic sensibility, a “fondness for art,” among the Jews, despite the long-standing belief that they had none. Toward those lofty ends, as an exercise in worthiness, a whopping 3,000 objects were put on display, ranging from documents and portraits to coinage, ritual objects and antiquities. “There was something to interest all tastes,” crowed the Jewish Chronicle of London.

While some contemporary British Jews—and several of their American counterparts—fretted lest the exhibition “publicly parade” too much of the Jews’ good fortune, others thought that exposure was precisely the point of the proceedings, an opportunity to “remove something of the mystery which somehow seems in the mind of the outside world to environ all that is Jewish.”

Whether the exhibition succeeded in demystifying the Jews is anyone’s guess. But there’s little doubt that among the thousands of visitors, whose numbers encompassed British Jewry’s “notabilities” and its school children, as well as the “sympathetic presence” of Christian clergy and “Gentile celebrities,” the exuberant Temple model made quite a splash.

How could it not? Every bit as, if not even more, detailed than the models that emanated from Schick’s hand, Newberry’s version had something else going for it: splendor, not just scholarship. Where the former literalized history, this one exuded wonder, generating awe and visual excitement. Much like King Solomon’s glittering creation, it, too, “flashed on its beholders.”

After a successful three-month run, the Anglo-Jewish Historical Exhibition closed its doors; every object on display, including the Temple model, was safely returned to its owner. And that was that. Or was it? In the absence of a paper trail, it’s hard to know whether this glorious rendition of King Solomon’s Temple ever saw the light of day again, prompting me on more than one occasion to ponder its fate.

I ponder no more. To my surprise and delight, I learned just the other day that it had not only survived the passage of time, but is currently on view, front and center, in Gallery 554 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Under the wing of the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, which received the object as a gift in 2019 and displayed it a year later, King Solomon’s Temple keeps company with other examples of the 19th-century’s “artistic virtuosity,” including exquisitely wrought candelabra and teapots.

Imagine that! Solomon’s Temple is now well within reach on Sundays through Tuesdays and on Thursdays, from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., and on Fridays and Sundays, from 10 a.m. to 9 p.m.

Jenna Weissman Joselit, the Charles E. Smith Professor of Judaic Studies & Professor of History at the George Washington University, is currently at work on a biography of Mordecai M. Kaplan.