Trees Grow in Brooklyn

Sephardic Jews built a safe haven around Ocean Parkway. Will the recent antisemitic attacks threaten our sense of safety?

Did you know that the elbow is the strongest point in the body? If you are close enough to use it in an emergency situation, you should.

Contrary to what Google and Fitbit tell you, do not take the stairs. Stairwells are dark, and isolating, and they make perfect crime scenes. Take the elevator, but run if there is a gun pointed at you, preferably in a zigzag direction.

These “tips” came to me in a text message group with five of my best friends. They were written by a police officer, and in light of the recent spate of hate crimes against Jews in Brooklyn—where we live—we were instructed to forward them to anyone we cared about. I sent the message to my mother, my sisters. I sent it to my husband. I forwarded it to another family group chat where there was a discussion about mace currently underway. (Was it true that you couldn’t ship it to New York or New Jersey?)

I hesitated, and then sent it my grandmother.

*

Tree-lined Ocean Parkway is the sun around which my community of Sephardic Jews orbits. In the fall, the leaves scatter along the promenade, creating a mosaic of reds and browns. Even in the winter, when the branches expose themselves as bony and bare, the trees have a fortress effect. At times they can feel suffocating. At others, comforting. Therein lay the Catch-22 of living within a community; its perimeters could feel protective and radioactive all at once. But whatever form, the trees remained, and seeing them meant I was home. I’ve never considered what they meant to others: the tourists taking the long route to Coney Island or the hip couple on an extended bike ride from a part of Brooklyn with a better name. I’ve never considered what they meant to my neighbors, those of different religions and races. To the dozens of microcommunities who, too, saw this tree-lined promenade and decided it was as good a place as any to start anew.

The possibility that someone might see these trees and resent—even hate—the people who dwelled around them, was always just that. A possibility. One that grew nearer when a man wearing a yarmulke was punched in the throat in Williamsburg. Closer, still, when three Jewish women were assaulted near a Chabad in Crown Heights. The tips from a policeman came when, moments from my parents’ home in Gravesend, a mother and her 4-year-old child were hit over the head with shopping bags.

I was writing a piece on the cultural significance of a modern household appliance: the freezer. I was pouring over interview transcripts with dozens of elderly women in my community whose journeys began in Aleppo or Damascus or Egypt and culminated here in Brooklyn, surrounded by the trees. They’d been through so much—religious discrimination in their native country, forced to put oceans between their parents and siblings. Many of them settled in Bensonhurst first, where a small Syrian Jewish community grew alongside Irish and Italian neighbors. The iceman would come around early each morning. An iceman! Could you believe it? If you wanted keep something frozen, you kept it in a box hung outside of your window.

It wasn’t like it is today (with the Sub-Zeros). Of course, it never was. But the freezer changed everything. The freezer made planning for spontaneity possible. It evolved, truly, to be the crown jewel of the home. My mother might allot a day to fill hers, with lahmajin and rolled yebre, glass Pyrexes lined with oil-soaked eggplant and heshu. Enough sambusak that when I’d spend Shabbat at her home, my 2-year-old in tow, I’d swipe two Ziplocs containing a dozen each and she’d barely notice. (The same couldn’t be said about Bounty.)

I’d grown accustomed to writing about things like this. Bangles dipped in gold and hors d’oeuvres that resemble half-moons and mass migrations to tropical destinations. I practiced faith without thinking about it—why would I? A few years ago, I began to comment on my practice. Sometimes, I even made fun of it—on the internet.

I was trying to make a latke using mostly spinach and egg whites when I heard about the attack at Rabbi Chaim Rottenberg’s home in Monsey, New York during Hanukkah. “It’s vile,” I told my husband, once I found the words. What I really wanted to say: If you didn’t know, you couldn’t tell we were Jewish just by looking at us.

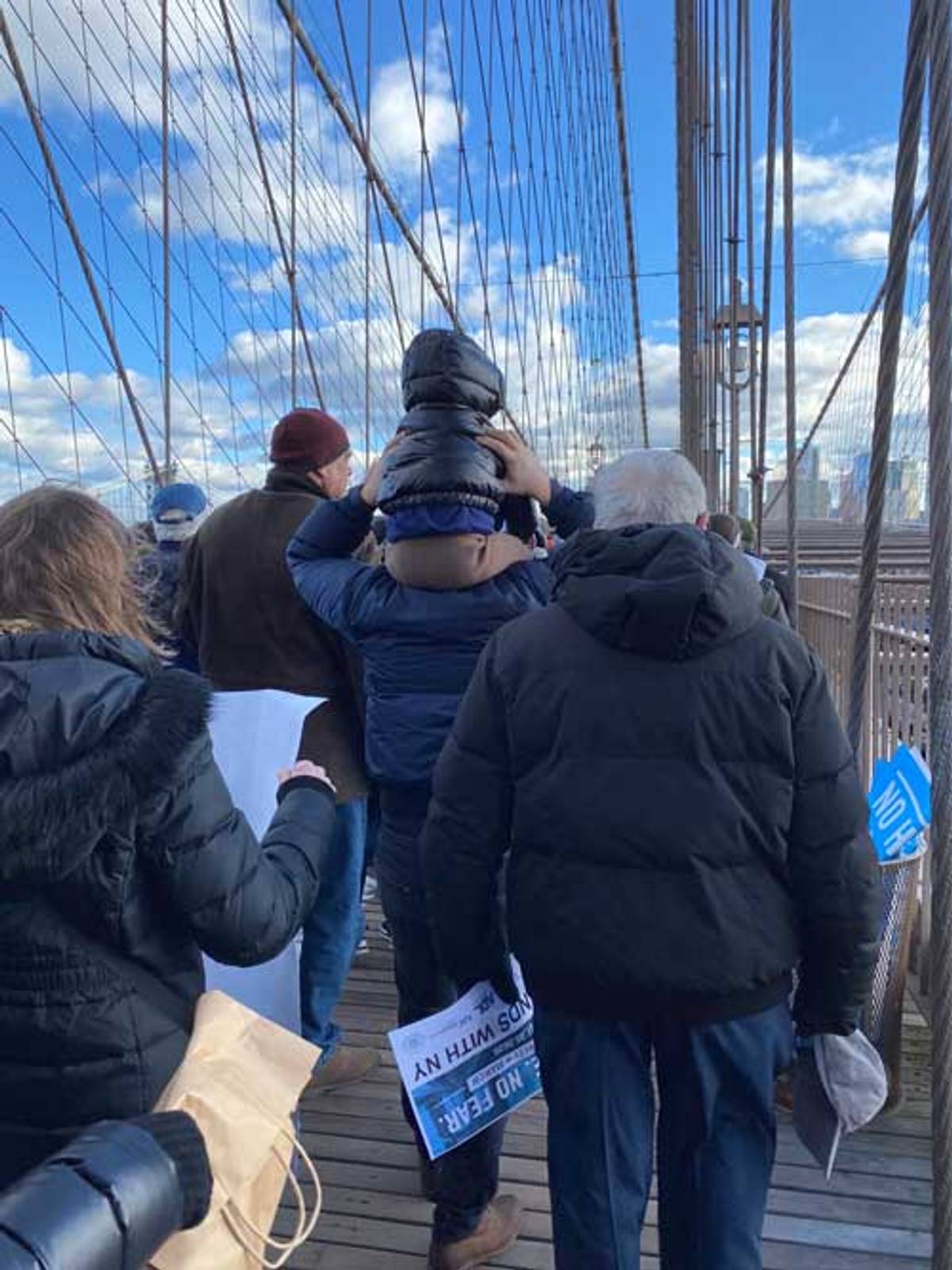

In January, 25,000 people poured into Foley Square to march for solidarity. Anne Frank and Martin Luther King Jr. were resurrected on oak tag and hoisted above a sea of hat and hair. The last chance to exit disappeared as we rounded a bend to enter the Brooklyn Bridge. It was 1:10 when the panic set in. Trust the body to the right of you. Trust the body to the left of you. Trust the body who’s been nipping at your heels for the last quarter-mile. Trust the nails and bolts that support all of you. What’s that smell? Can you not stomp your feet so aggressively?

No hate, no fear.

My Grandpa Maurice, I thought, would hate this. My grandpa, who fled Egypt for Paris and then Brooklyn, would rather watch basketball over a hot plate of foul than participate in a march claiming to protect his right to safety in America. My grandpa would tell you that to your face, too. If I were a betting woman, I’d say that my Grandpa Nissim would sit this one out as well. Nissim, my mother’s father, who didn’t know his own birthday so it was celebrated on Hanukkah. Nissim, who drove a massive white truck wracked with graffiti and shuffled around Bedford Avenue wearing pants that were too big, a wad of cash wrapped in a rubber band, stuffed in his sock. Who sometimes would give me a dollar or five to clean up the Israeli newspapers strewn on the floor of his apartment. But before all that, before the ministrokes and then the massive one, before the induced coma and the diabetes diagnoses, Nissim Sasson had a life in Aleppo and another in Haifa but I wouldn’t know much about that, because I never really asked.

Both of my grandparents would’ve looked at the Instagram photo of my son levitating above the mass of bodies at the rally, propped up on my husband’s shoulders and said, “It’s Sunday. Take him for candy.” Perhaps it’s easier to march for solidarity when you’re two generations removed from the fight it took to get here. I suspect that for many elders in my community, acknowledging that there is still a war to be waged is a bitter pill to swallow. Haven’t we already won? We’re here, aren’t we? Living in beautiful homes surrounded by the trees, with choices to make. Which synagogue to worship at? Which yeshiva to enroll our children in? We tend to rally around our own, sure, but we’ve worked hard to acclimate to American society; in business and in the way we dress. This victory should last a little bit longer, shouldn’t it?

One time, a classmate in my liberal-leaning seminar at my small liberal arts school within my larger, liberal arts university told me: You know you’re not white, right?

Mayor de Blasio provides a name for what’s been happening to us: “anti-Semitic crisis.” Various politicians call for various tasks forces in various neighborhoods and I think, will this be read as favoritism? How much is our protection worth when measured up against someone else’s hate? A nagging voice reminds me that it could always be worse. It is worse, for most people. And again, you wouldn’t know we were Jewish just by looking at us. Unless you saw the trees, and they meant something else to you.

The other day, someone who I trust to give me the news told me that the future for Jews in America is very dark. And in Europe? This person whom I trust says, forget about it. Or, as a sign on the Belt Parkway East reads as you’re leaving Brooklyn: Fuhgeddaboudit.

*

A professor in my MFA program once told me to approach writing about my home like an anthropologist. I try to walk down Ocean Parkway like a stranger but keep getting distracted by a familiar face. I try to stay angry over a difference in political opinion but there is so much more that binds us than tears us apart. I try not to show my mother how relieved I am to be home for Shabbat. I don’t fall apart at the notion of living within arm’s reach of my parents and my in-laws. I buy a Syrian cookbook. I buy another. I spend six hours cooking four different types of jibben for my toddler, who loves jibben, and recognize this as a victory, not a defeat.

I store them in my freezer.

At the moment, I feel comforted by the trees.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Esther Levy Chehebar is a Brooklyn-based writer. She is currently at work on a novel loosely inspired by her Syrian Jewish upbringing.