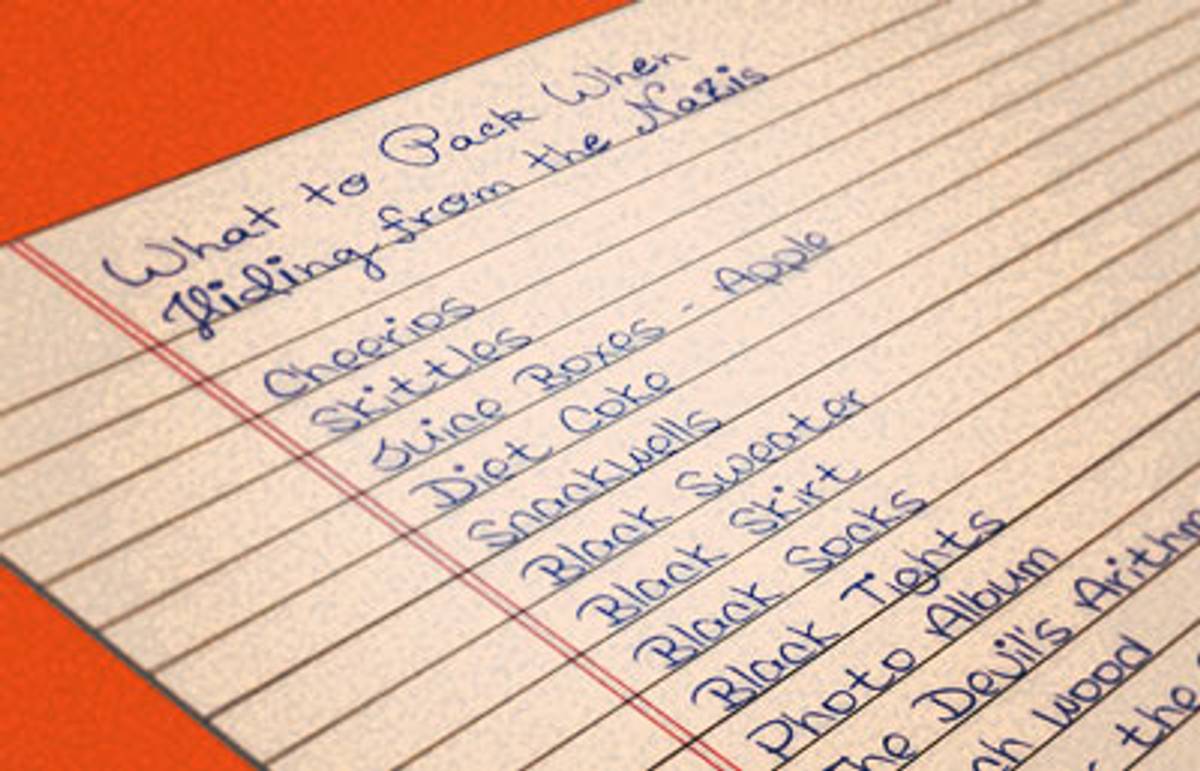

When I was growing up, the Holocaust haunted me. In a valiant attempt at control in a hostile and uncertain world, a world that was once capable (and could be again) of hunting down Jewish children and sending them to their fiery deaths, I took out my Lisa Frank notebook—a luridly colored affair with a pair of grimacing kittens dressed as ballerinas pirouetting across the cover—and made lists. Lists with titles like “People who would hide us from the Nazis,” “People who would probably turn us in to the Nazis,” and of course, “What to Pack When Hiding from the Nazis.”

The items on the latter list were the most self-evident: One would need food, of course, Ziploc bags of Cheerios and Skittles, apple juice boxes, and cans of Diet Coke from the pantry. Family photographs—I’d want images of my annihilated relatives to occupy a place of honor at Yad Vashem. A few suitably depressing items of clothing and, finally, books. The books were the most important. Even an activity as challenging as fleeing the Gestapo was bound to include some downtime, and the titles I packed were chock-full of helpful hints, sure to help me out of any jam or rat-infested crawlspace under an abandoned Warsaw building where I and three others lay hidden, eating rotten potato peels and creeping in the dead of night to relieve ourselves in the frozen sewers. I speak, of course, of the genre known as Young Adult Holocaust literature, a body of work specifically designed to remind Jewish children that no matter how safe they might feel, there will always be those who wish to destroy them. As one perspicacious young reader observed in his “Kid’s Review” (in the name of research, I browsed a few such tomes on Amazon recently): “Would you want to be a jew when you are getting ready to be killed by the germans I wouldn’t.”

There was Touch Wood: A Girlhood in Occupied France by Renee Roth-Hano, outlining how to pass as a convent-educated Catholic. I learned the appropriate times to cross oneself (out of fear, reverence, or superstition), invoke a saint (for a lost object, a difficult problem, or when beset by a pack of thieves), and that Frenchmen who refer to Jews as “wily Israelites” are less virulently anti-Semitic than those who prefer the more traditional “filthy Christ-killers.” The Island on Bird Street by Uri Orlev taught me how to burrow under the ghetto wall, how to keep and shoot a gun, and that the only person you can really trust is your pet mouse. And in Number the Stars by Lois Lowry, I discovered the importance of being Danish.

Such tales of woe were plentiful, yet unlike their real-life counterparts, these brave, benighted children, these Henryks and Hannahs and Boleks and Shmuliks, rarely wound up in Auschwitz. They might lose all their earthly possessions, be assaulted by classmates and teachers shouting racial epithets, even have parents or younger siblings murdered before them (all events deemed appropriate for young readers and beneficial to the formation of their Jewish identities), but clearly the experience of a death camp, even fictionalized, was just too scary. There was, however, one notable exception: The Devil’s Arithmetic by Jane Yolen.

It was like a dare, that book. To have read it—not just to have checked it out from the library and stared at the cover, paralyzed with fear for three or four days, but to have actually read it—was a kind of status symbol. It marked you as a force to be reckoned with, a deranged loose cannon, the kind of kid who would stick her hand in a tank of piranhas or say “Bloody Mary” three times in the mirror at midnight with a death wish in her eyes. The others would whisper about you in car pool before they picked you up on the first day of school, like you were Dennis Hopper. Don’t mess with her. She’s crazy. Loco. Read The Devil’s Arithmetic cover to cover and ain’t been the same since.

While the film adaptation starring Kirsten Dunst has somewhat deflated its epic creepiness, The Devil’s Arithmetic is probably the most frightening book ever written for children. It’s certainly the most frightening book I’ve ever read. The chilling premise is this: Hannah Stern, a modern thirteen-year-old girl, prefers the company of Gentile friends to studying for her Bat Mitzvah and is weary of visiting her elderly grandfather, a semi-catatonic concentration camp survivor who spends his days parked in front of the Hitler—I mean, the History—Channel, weeping uncontrollably. “I’m tired of remembering!” she exclaims. Well, as every Jewish child who has had his Hebrew school class visited by an itinerant representative of the Anti-Defamation League knows, he who does not remember history is condemned to repeat it. I think it’s printed on the mini-Frisbees they hand out after they’ve finished terrifying you. For Hannah, with her casual disregard for the suffering of her elders (and at thirteen, she should really know better), this concept will take a particularly vivid form. Upon opening the door for Elijah at her grandparents’ Passover seder (to which she has come grudgingly—bad girl! Bad JEWISH GIRL! ), she feels a strange breeze across her face and is mysteriously whisked away to… the magical land of Birkenau!

The fish-out-of-water/new-kid-in-school scenario is very common to children’s literature, playing on a child’s fear of strangeness, loneliness, of not belonging. Most of these stories, however, do not feature Josef Mengele as a supporting character. But eventually Hannah, with a little help from her fellow inmates, masters the camp rules for survival—basic bowl-and-potato etiquette, exploiting the lesbian tendencies of the female guards, and of course, “never stand next to someone with a G in her number. G means Greek, and the Greeks don’t last long”—only to discover that such rules are merely a superstitious construct devised by the prisoners to delude themselves that they can somehow subvert, or at least delay, the inevitable, and lo, the ungrateful little JAP gets sent to the gas chamber. Ha! That’ll learn her!

But lucky for Hannah, instead of paralyzing her central nervous system as she claws futilely at the walls with her fingernails until finally suffocating to death in agony, the gas transports her safely back to her own time like three clicks of a pair of ruby slippers, sadder, wiser, and presumably more willing to call her grandparents once in a while. Maybe even come over, spend a little time, would it kill her? No, it wouldn’t. Typhoid, sadistic medical experiments, the hungry Rottweilers when you get off the cattle car, that’s what kills you. Bubbe and Zayde only want to see you once in a while, is that such a crime?

The message was hardly lost on me. And as I practiced taking apart the showerhead to check for Zyklon B pellets before I turned it on, I noted to myself that if anyone was going to open the door for Elijah at the seder, it was going to be my sister. She was almost five years younger than me and hadn’t even started kindergarten yet; she had a lot less to live for.

This is what we were raised on. These were the stories that filled our heads—I’m speaking in the Rothian “we” now, the “we” that means every Jewish person of my generation anywhere in America. Our parents’ generation, the baby boomers, had focused on happy Jewish things like the state of Israel and Sandy Koufax. They seldom spoke of the Holocaust at home or at religious school. It was too recent, too vivid, too painful a reminder of the world’s cruel indifference. But we could take on this burden, this legacy of unspeakable pain. Enough time had passed. We wouldn’t be crushed under the weight.

I attended a Jewish day school, and my class had an ongoing assignment: Once a week we were to find a newspaper article that featured some Jewish content, cut it out, attach it to a sheet of notebook paper with a staple or paper clip (we were not to use Scotch tape, although neat gluing was permissible), and on the notebook paper, in pen, inscribe a brief summary of said article. The definition of “Jewish content” was fairly relaxed—a piece concerning a certain Aaron Spelling show might be acceptable, or, depending on our teacher’s mood, a review of the new Billy Crystal movie—as was the standard to which our summary was held; a typical sentence might read: “What is Jewish about this article is that it is an article about Israel which is the Jewish country so as you can see this article has something Jewish about it.”

It wasn’t difficult to find such a story. Jews—not to mention their antagonists—manage to keep themselves in the news. There was always a snippet about Yasser Arafat or Jeffrey Katzenberg somewhere, and in a pinch there was The Jerusalem Post my father received in the mail twice a month, in which everything, even the want ads, was Jewish. And it was in this paper, as I struggled to complete my homework in the thirty minutes between The Golden Girls and L.A. Law one evening, that I discovered the item that would destroy my mind and haunt my soul, that would finally push me from the rocky precipice of sanity into the chasm of Nazi-induced psychosis.

It was here that I first read about the Mengele twins.

Ominously titled “The Girl in the Cage,” it was a first-person account from a survivor of the horrifying and perverse medical experiments the Auschwitz camp doctor, nicknamed “the Angel of Death,” performed on sets of twin prisoners, mainly children. Don’t, I told myself, staring wide-eyed at the accompanying ink drawing scratched in a stroke so rough it looked painful. Stop reading. Find some little piece about Teddy Kollek and call it a day.

I was nine, but I remember everything in that story like I read it yesterday. How she and her twin sister were discovered hiding under their mother’s skirt as they disembarked from the cattle car with cries of “Zwillinge! Zwillinge!” (“Twins! Twins!”), and were ripped from her arms as she was sent to her death. How the twin girls were locked naked in a small cage and given injections that gave them seizures. How one day, her sister seized so violently she was taken from the cage and never returned. The unanesthetized, pointless surgeries, the cutting into her leg to scrape at the bone with a scalpel, the chemicals dropped in the eyes to see if they would change color, the chilling times they would sit nude on Mengele’s lap, as he petted them fondly, speaking in soft, fatherly tones. And of all the twins kept for torture in the medical block, this girl and her dead sister, four years old when they first arrived, they were the lucky ones. They weren’t subject to experimental hysterectomies or sex-change operations. They weren’t sewn together back-to-back like the Gypsy twins Mengele had tried to conjoin artificially, who screamed for three days until the gangrene killed them.

Like all children, I was warned from the time I was very small of the peril of talking to strangers. Strangers harbored all manner of unsavory intentions, and a stupid or greedy child taken in by their offers of candies or bicycles was sure to find himself covered with cigarette burns and gagged and bound with electrical tape in a rat-filled subterranean chamber, forced to submit to all kinds of disgusting adult demands involving his private parts. Nearly hysterical one day, I confided my fears to my mother, who consoled me. Most strangers were perfectly nice people, she said, with no intention of hurting children or their private parts. But there were a few bad apples out there, not many, but a few, and it’s a shame that they were the ones we heard about, but that’s the way it was.

“Don’t worry too much, baby,” she said, stroking my hair. I buried my small, damp face in the comforting curve of her chest. “You can’t go around being afraid all the time. And you know that Daddy and I will protect you, no matter what.”

However, the evening I came to her with my Mengele problem, she was in a lighter mood.

“Dr. Mengele, huh? Maybe that’s who we’ll send you to the next time you’re ‘too sick’ to go to school.” She giggled, greatly amused. “Oh, a leetle Jewish girl mit a sore throat? Vell, vee vill RIP her throat out and zen it von’t hurt anymore!”

I gazed at her silently, ashen faced and ill.

“Oh, come on, sweetie. It’s a joke.”

“Jokes are supposed to be funny,” I whispered.

She rolled her eyes. “Jesus Christ, will you lighten up? Go finish your damn homework—it’s almost time for L.A. Law.”

She had lied. My mother had lied. Most people were not nice. Most people looked at you and saw a target, a victim, someone to be abused, tortured, exploited for political or professional gain. A helpless plaything upon whom the world’s monsters might inflict their own hate-filled perversions, their darkest, basest desires. Such was the nature of being a child. Such was the nature of being a Jew. And by that logic, was not a Jewish child the worst thing to be? They were everywhere, the bad people. They were still out to get us, all of them, biding their time, ready to pounce at the proper moment, when the world was once again susceptible to hatred. Everywhere. The neo-Nazi skinheads who grimaced from the envelopes of Anti-Defamation League fundraising letters; that girl with the giant pink glasses from preschool who told me that Jews were not God’s Children; the mild-mannered mechanic, embedded quietly in some Ukrainian community in Michigan, who turns out to be an infamous death-camp guard who made people eat their own ears. My mother said she would protect me from such horrors, that she and my father would keep me safe. Another lie. Where were all those other mothers? Where were the Mengele twins’ mothers? Dead. Gassed. Dead, gassed, and useless.

Downstairs, I could hear the first strident bars of the L.A. Law theme song.

“Sweetheart?” my mother called up the steps. “Sweetie?”

I took a deep breath. “Yeah?”

She paused, taken aback at the palpable fear in my voice. “Do you want some ice cream?”

Fool. Ignorant of the gathering storm that soon would shatter our comfortable little lives into a million bloody pieces, she dug deeper into her carton of Edy’s Grand, dribbling some down the front of her freshly laundered nightgown, while the television—The television! The infernal soundtrack that blocks our ears, our minds, from truth!—flickered across her blank, doomed face. She was watching L.A. Law; she couldn’t miss L.A. Law. But where would she be when they came for Benny, the retarded guy? When they came for the red-haired English lesbian who came on this season? Still watching, still spooning low-fat chocolate chocolate chip into her mouth? Spoon away, old friend, spoon away. Because when they come for Douglas Brackman, when they come for Stuart Markowitz, it will be too late. Too late for us all.

I didn’t sleep that night.

Or the next night.

Or the night after that.

For there in the walls of my bedroom, walls painted in the palest china blue, a color I had chosen myself from the book of paint chips the decorator had brought, creeping so lightly, so stealthily, that senses less acute than mine, brains less agile, might mistake them for the scuttlings of a mouse, there, inside my walls, were the Nazis.

Nazis! Gray eyes glinting in the flickering light, canine ears pressed tightly to the drywall, long-bridged noses, slim and elegant, filled with the scent of the wretched Jew-child. They missed nothing. The moment I closed my eyes would spell my doom, for at this moment they would pounce, and oh! What fresh Hell awaited this helpless Daughter of Israel! But I would not go easily. I would not doom my body to the ash heap. I would not be but another faceless victim, another nameless number, another faggot (in the bundle-of-twigs sense) for their grisly fire! Not I! Not this night!

* * *

“We need to talk,” said my mother. The ballet car pool had just dropped me at home.

I wriggled impatiently, anxious to fix some microwave popcorn and return to my copy of Nuremberg Diary. “Um, not now, okay?”

“I got a call today from Mrs. Finkel.”

“Mrs. Finkel?”

“The librarian. You know, at the Jewish Community Center. She’s friends with Grandma—”

“I know who she is. How did she get this number?” I demanded.

“What do you mean, how did she get this number? Probably she got it out of the Hadassah directory, the same way I would get her number.”

Nearly every Jewish woman and girl in the country belongs to Hadassah, the Women’s Zionist Organization of America. The local chapter directory is a veritable who’s who of area Jewish females. Earlier that week, I had casually mentioned to my mother that we might consider terminating our association with the organization and withdrawing our names from its records, as when They came for us, the Hadassah directory would likely be the first place They’d look.

“Mrs. Finkel told me that you tried to check out all four tapes of Shoah this afternoon.”

“So? You’re allowed to check out all four tapes! They come as a set! It’s like checking out one tape!”

She was still making that damn face. I hated that face. “She told me it was the seventh time you’ve tried to check it out in the past three weeks.”

“So what? She kept saying it was reserved.”

“It’s on the thirteen-and-over list, honey.”

“Meaning?”

“Meaning you have to be thirteen or over to check it out. That’s the rule.”

“That’s the first I’ve heard of any such rule.”

“Sweetie, that’s the rule.”

“IT’S A BULLSHIT RULE!”

My mother’s shrill temper flared at last. “And when were you planning to watch all NINE AND A HALF HOURS OF SHOAH, HUH? Were you going to take a night off from whatever weird fucking shit you’re doing to the walls of your room when the normal people are asleep?”

Never content to let a long period of insomnia pass unproductively, I had kept myself busy in the restless wee hours cutting out pictures of famous Jews from magazines and sticking them on the walls of my bedroom with bits of chewed gum, where they acted as talismans warding off the unspeakable evil that lay in wait. The resemblance to Anne Frank’s famous bedroom wall in the Secret Annex, touchingly adorned with colorful postcards and newspaper ads picturing film stars and babies, was not lost on me; however, I reasoned, if poor Anne had only been a bit more judicious, a little more ethnocentric in her selections, things might have turned out differently. The Gestapo wasn’t going to get me, not with that giant picture of Henry Kissinger on the wall.

“I shudder to think how many times in a row you could watch that goddamn thing,” my mother continued, shaking her head. “How many fucking times did you sit through The Birth of a Nation last summer? Seventeen? Eighteen? Enough times to make a sane person psychotic—God knows what it did to you.”

I began to cry.

“Honey, tell me something.” She looked thoughtful. “What happens to you when you start to have scary thoughts?”

My cheeks flush. My heartbeat veers wildly out of control. I start to claw at my skin like it’s a canvas bag I’ve been tied in, a canvas bag filled with rats. My stomach churns. I feel like I’m going to pass out, throw up, or, failing those, throw myself out a window, hoping pain or death will distract me. “I don’t know,” I said.

“Okay.” She pursed her lips again. It’s not easy to be the mother of a schizophrenic third-grader, but oy; what are you gonna do? “Tell me something else. Do you ever think of anything besides the Holocaust?”

The Holocaust. I gasped a little at the sound of it. I had stopped using the word. It hung in my head, unspoken, un-thought-of, like the name of a crush one dares not speak aloud, lest by some Mystical Power of Boy, he should hear it, and abruptly, heart-wrenchingly, withdraw his presence from your lunch table, and if that happened, you might as well not even go back to school. You might as well not even live. You might as well rip the picture of Woody Allen off your wall and let the Nazis come get you.

“Do you ever think of anything besides the Holocaust?” She was waiting for an answer.

“Sometimes. But then—”

“Then what?”

“Well, if I find myself not thinking about…it…then I make myself think about it. I’ll think about something I’ve read or some picture I saw, and I won’t stop thinking about it until I can’t stop thinking about it.”

“Why don’t you let yourself not think about it? What do you think is going to happen?”

“Those that do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” I intoned solemnly. Surely this would end the conversation. I could creep to my room, finish reading Ribbentrop’s testimony to the war crimes tribunal, and enjoy the ensuing surge of terror in peace and quiet before dinner.

“Who said that?” my mother asked.

“I don’t know. Maybe Elie Wiesel?”

“No! Who said that to you?”

“Oh.” I almost laughed. “Everyone.”

“Everyone? At school?”

School, Hebrew school, every work of Jewish children’s literature I had ever received as a prize or present, every piece of spiky Holocaust memorial sculpture displayed in a Jewish Community Center lobby with a title like Remember Not to Forget or Six Million…and Counting.

It was not yet acceptable for pediatricians to prescribe antianxiety medication to small children, nor was she about to launch a verbal attack against a Jewish community and education system that with its overwhelming emphasis on victimhood, its insistence that the youngest and least of its brethren experience the same level of psychic pain as its elders in penance for growing up in a country and time relatively free of hatred or danger, leads to a kind of retroactive survival guilt that would ultimately manifest itself in their unformed psyches in one of two ways.

So my mother just said, a little sadly, “Listen to me. The next time you find yourself having those thoughts, I want to you to close your eyes, count to three, and then, as loud as you can, I want you to shout ‘STOP!’ Okay?”

“STOP!” I shouted.

“No! To yourself!” My mother clutched her ear. “Shout in your head.”

I shouted in my head for months. My mother, continuing her good work, banished most of the books from my shelves, replacing them with The Baby-Sitters Club and, against her better judgment, Sweet Valley High. “I’d rather have you shallow and sexually precocious then morbidly psychotic,” she said. Eventually, the thoughts began to recede. I managed to say the word Holocaust aloud. I no longer checked the showerhead for gas or packed small bags full of socks and SnackWell’s, and when it was released in theaters a few years later, I managed to see Schindler’s List with a friend of German-Catholic descent and did not become hysterical—although we had smoked an oddly strong joint in the parking lot before the movie and were forced to discard our popcorn when it began to remind us of a jumbo tub of buttered human teeth, refillable with proof of purchase.

But true salvation would not come until I was in Auschwitz.

I was on a Jewish teen tour, with hundreds of other Jewish teenagers from all over the country—somehow it seemed fitting that my first personal encounter with the death camps should also be my first with the Jewish youth of Long Island and New Jersey.

After a week spent methodically pulverizing what little faith in humanity we had left, we would spend the second week visiting the glory, wonder, and triumph of the Jewish spirit that is the state of Israel, and in this way would our parents ensure that we would grow up to be the kind of people who would marry other Jews, send our children to religious school, and, after we had built up our medical practices, begin to contribute significant chunks of money to the proper federations and charities.

I was told this experience would change my life.

We spent a bit of time orienting ourselves to our surroundings, recovering from jet lag, surveying the delicate peer dynamic of our new community. Soon we were prepared to begin the important business of hysterical weeping.

Which was what I was doing, crumpled against the pillar in the Sorting Room at Auschwitz. We had walked slowly around the cavernous space, examining the enormous mounds of things that had once belonged to people—the mountain of hair, a chamber crammed with children’s toys. The faces of even the toughest and angriest among us were streaked with tears, but my wails must have been particularly wrenching (or ostentatious), for almost at once, I felt an arm softly draping my shoulder.

It was Bettina, a tiny blond woman in her seventies. Several Holocaust survivors were traveling with us, but Bettina was by far the best loved—and the least haunted. I turned slightly to look up into her kind face, and she wrapped her arms around me at once, cradling me like a mother.

“Shhh, darling, sha. Don’t cry like that. Don’t cry.”

“I can’t help it!” I blubbered.

“I know, sweetheart. I know. But not like that. Listen to me, darling. You shouldn’t carry our pain,” she said, wiping the tears from my face with a folded Kleenex, slightly damp. “Our pain is ours. We don’t need you to feel it for us.”

“But all the people….” I couldn’t stop. “All the things.”

“They’re just things, bubbeleh. Just things.” She gestured toward a huge case. “And think, maybe some of the people that used those things, they’re still alive somewhere!”

I followed her hand to the case full of empty cans of gas pellets.

“Okay,” she said. “Not those maybe. But look. Those shoes. Maybe, would you believe it, somewhere in there is a pair of my old shoes? And I’m standing here with you, darling. You see?”

“Isn’t it painful here for you?” I asked. “To be here?”

Her eyes darkened. “Painful? Yes, sweetheart, of course. But I’ll tell you what. It’s a lot better than the last time I’m here.”

I laughed out loud, and a girl nearby stopped sobbing for a moment to glare at us. Bettina plunged an arm into her enormous handbag and extracted a wrinkled Halloween-sized packet of M&M’s. “Here,” she said, patting my cheek. “Take.”

I took.

“Eat!”

I ate.

From Have You No Shame? by Rachel Shukert. Copyright © 2008 by Rachel Shukert. Published by arrangement with Villard Books, an imprint of Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc.

Rachel Shukert, a Tablet Magazine columnist on pop culture, is the author of the memoirs Have You No Shame? and Everything Is Going To Be Great. Starstruck, the first in a series of three novels, is new from Random House. Her Twitter feed is @rachelshukert.

Rachel Shukert is the author of the memoirs Have You No Shame? and Everything Is Going To Be Great,and the novel Starstruck. She is the creator of the Netflix show The Baby-Sitters Club, and a writer on such series as GLOW and Supergirl. Her Twitter feed is @rachelshukert.