That Voodoo That You Do

The history of the religion in New Orleans and beyond—and how it differs from the touristy kitsch peddled today in the French Quarter

In recent years, “zombie crossing” decorations, zombie 5Ks, and even zombie paintball hunts have been ubiquitous at Halloween. While the connection has all but disappeared from the contemporary swift-running, virus-infected zombie genre, for most of the 20th century the walking dead were closely associated with Voodoo, which books and movies tended to portray as something lurid, exotic, and sinister. To the extent that Voodoo remains in the American popular consciousness, one likely factor is its association with New Orleans, where enslaved people practiced rites and rituals that blended West African religion with Roman Catholic imagery and beliefs. Today, modern-day practitioners of Voodoo remain active in the city, as does a history that interweaves race, class, suffering, and survival.

New Orleans was the epicenter of Voodoo in early America, and the practices there bore (and continue to bear) little resemblance to the tourist kitsch that permeates the French Quarter today, from overpriced Voodoo-doll keychains to Voodoo-themed chicken and daiquiri restaurants. This past August, I attended a workshop on New Orleans Voodoo with Voodoo priestess, filmmaker, author, editor, publisher, and blogger Lilith Dorsey at the city’s annual Hexfest conference. While in New Orleans, commonly referred to as the northernmost city in the Caribbean, I encountered more than one local who spoke proudly of Voodoo’s legacy of resistance to oppression and bigotry—one very much at odds with its malevolent popular image.

The first enslaved Africans arrived in Louisiana in 1719, around 20 years after French settlement was established. With them, according to author and Voodoo researcher Carolyn Morrow Long, came their religious practices, mostly from West and Central Africa, which they combined with what she calls in a 2002 journal article “the folk Catholicism of the colonists.”

Long writes in the same Nova Religio article that New Orleans Voodoo eventually developed a distinct identity from Haitian Vodou, on which it had originally been patterned. Like the Haitian variety, it is centered around lwa, spirits or subordinate deities who mediate between believers and a supreme deity. In Louisiana, however, the lwa gradually shifted their associations from West and Central African deities to Catholic saints with similar characteristics or patronages. (The snake lwa Damballa, for example, is often celebrated by Voodoo practitioners on the feast of St. Patrick, who legend says drove snakes out of Ireland.) Possession by the lwa is considered a common and desirable spiritual experience in Vodou, in which the spirit “mounts” the believer to communicate with believers. Long wrote that the original lwa names from Africa that are used in Haitian Vodou seem to have been largely replaced by their associated Catholic saints in Louisiana by the end of the 19th century.

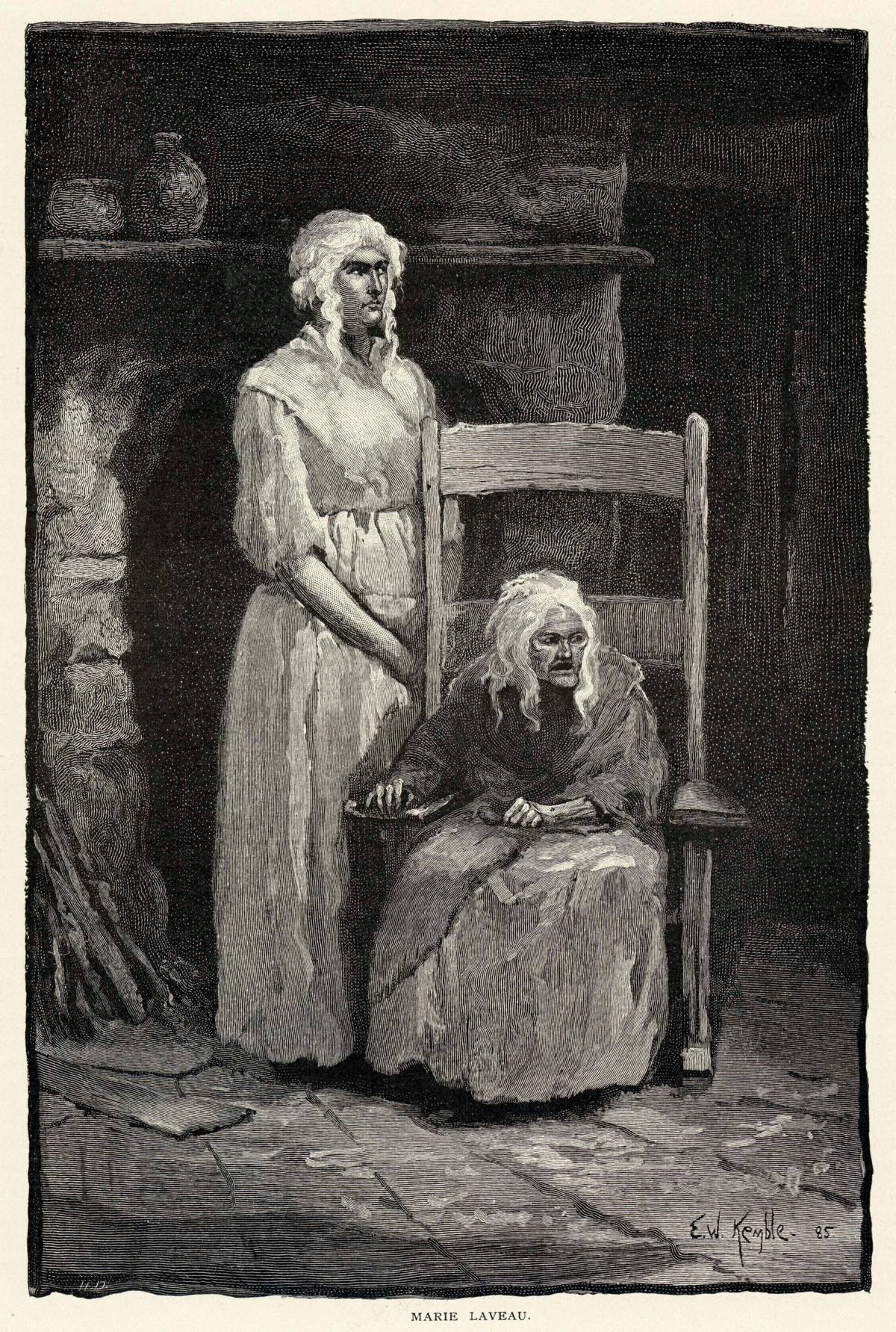

Earlier that century, Voodoo had attained immense cultural significance in New Orleans through the influence of the formidable “Voodoo Queen,” Marie Laveau. The tomb of the Voodoo icon, who was also said to have been a devout Catholic, is located behind the oldest church in the city, in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1—closed to the general public a few years ago after intensifying and high-profile vandalism. (The 18th-century cemetery is also the future resting place of Nicolas Cage, who, pharaohlike, has had a pyramid constructed for himself among the avenues of family-owned mausoleums.) Its capstone is visible from the cemetery wall, which is covered in myriad graffiti X’s drawn by petitioners to symbolize their requests of the deceased Laveau to work her magic from beyond the grave. On a city cemetery tour that picked up at the Irish Cultural Museum (in reality, a very homey bar with some infographics about the Irish experience in Louisiana), I learned about Laveau’s reputation as a powerful Voodoo practitioner. Her one-of-a-kind status allowed her to cross barriers of race, gender, and class in antebellum New Orleans.

Her influence is still felt today. When I told locals I was in town to write about Voodoo, more than one brought up Laveau, and on two separate occasions, men preemptively leapt to her defense against her occasionally tawdry popular image. With asynchronous chivalry, they eagerly informed me that Laveau was an influential advocate on behalf of the marginalized in the New Orleans of her day (which is believed to have spanned almost all of the 19th century). A free Creole woman, she is thought to have begun her career as a hairdresser to the wealthy and powerful of New Orleans society, which would have facilitated her influence and movement between antebellum castes. Much of her life is shrouded in mystery and legend, though, which makes it difficult to say much about her with certainty. First, there is the year of her birth, which was maybe in the 1790s, maybe at the dawn of the 1800s. There is also the confusion created by accounts of her daughter, also named Mavie Laveau, who was said to have strongly resembled her, and who was also a Voodoo practitioner. Additionally, sensationalized, voyeuristic accounts by (typically white) outsiders of gatherings over which Laveau likely presided contributed to a general air of suspicion around Voodoo.

Vodou provided a strong sense of cultural and religious identity to enslaved rebels during the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804). Occurring contemporaneously was the Louisiana Purchase in 1803; Long wrote that U.S. authorities in the newly acquired region, who already regarded Catholicism as decadent Latin superstition, had their WASPy fears and bigotries stoked by the accounts of violence against the white colonists at the hands of the rebels. The Haitian Revolution cast a long shadow in the American imagination, and the establishment continued to present Voodoo as a lurking menace to public order. Long’s Nova Religio article, “Perceptions of New Orleans Voodoo: Sin, Fraud, Entertainment, and Religion,” contains an 1859 description in the New Orleans Daily Crescent of the alleged goings-on at Marie Laveau’s house and the “hellish observance of the mysterious rights of Voudou,” which it described as “one of the worst forms of African paganism, and is believed in and practiced by large numbers of negroes in this city, and by some white people. A description of the orgies would never do to put in respectable print.” By contrast, Long includes in her article an eye-witness description from a participant in one of Leveau’s ceremony, which included altars with crosses, pictures of saints, the Our Father prayer, and “creole dance,” followed by a convivial dinner.

Although of Black descent herself, Laveau’s clientele was racially mixed, with one contemporary account describing them as frequently “more white than colored.” And her perceived ability to affect outcomes for them through ritual was only one source of her influence. She was also described as a high-profile philanthropist, purportedly assisting orphans, visiting death row inmates, paying bonds for Black women who had been arrested, and advocating for prisoners in the courtroom. “Marie would often visit the cells of the condemned,” her New York Times obituary read, “and turn the thoughts of those soon to be led out to atone for their crimes to their Saviour. Her coming was considered a blessing by the prisoners, because if they could only excite her pity, her powerful influence would often obtain her pardon.” This type of influence in a city where Code Noir laws prohibited interracial marriage, voting, or holding public office, cannot be underestimated.

A review in the journal Caribbean Studies of a 2006 book by Long, A New Orleans Voudou Priestess: The Legend and Reality of Marie Laveau, takes issue with what the author sees as a lack of hard evidence and a preponderance of conjecture about Laveau’s life in the book. However, this lack of documentation is perhaps unsurprising given Laveau’s status as a woman of color living in the 19th-century American South. Ultimately, whatever the reality of her life, abilities, and influence might have been, her ongoing power as a legend is undeniable, and she endures as an iconoclastic symbol for marginalized voices.

Texas death row inmate and artist Rob Will wrote of Laveau’s legend in a 2020 blog post about a triptych he painted of the beloved Voodoo Queen. For Will, who is fighting what he claims to be a wrongful murder conviction, Laveau serves as a Joseph Campbell-style “creative hero” who moves and guides society toward salvation. Will gets at her symbolic power when he writes about his portrayal of her, which he says on a surface level honors Laveau’s humanitarian and social justice legacy, but might also just “spread the delightful metaphysical Energy of the magic of the Voodoo Queen of New Orleans” at the same time, which, he asks, “is much more fun, isn’t it?”

Most Americans might not associate Voodoo and “fun,” per se, at least beyond the mild frisson of proximity to something with a lingering air of taboo, such as a French Quarter Voodoo tour, or seeking a Voodoo-tinged psychic reading from one of the many self-proclaimed fortune tellers in Jackson Square. But at her New Orleans Voodoo workshop at Hexfest this summer, Lilith Dorsey spoke earnestly to attendees about her faith while employing colorful, irreverent anecdotes, which she punctuated with frequent jokes and laughter. The pictures in her accompanying slideshow featured smiling group shots of affable-looking people, and she spoke warmly about friends from her practice who had died as if they were still alive, and might walk through the door at any moment.

A committed practitioner, Dorsey was keen in her presentation to set the record straight about her religion: Voodoo dolls? Not a thing (employing a “poppet” for sympathetic magic comes from European traditions, she said). Evil? Hardly, and to suggest so, she has written before, is offensive. Orgiastic frenzies? “Nothing could be further from the truth,” she said. Far from tales of zombies come to life and demonic possession, in her blog Voodoo Universe (housed on the world religion blog clearinghouse Patheos), Dorsey writes about an effort that would be considered praiseworthy by nearly any faith group’s standards: standing up a community garden in New Orleans’ Ninth Ward, designated a “food desert” by the USDA. In her workshop, she mentioned an effort undertaken by herself and some associates to send representative dolls to disadvantaged children of color. Dorsey reiterated a theme in her lecture that she’s written about before on her blog: The popular focus on hexes and curses as key components of Voodoo misinterprets the experience of people of color under colonial oppression. Lacking any sort of justice or protection in the secular realm, they adopted practices from their spiritual traditions to try to secure those things for themselves.

White, traditional Christian cultural influence continues to distort this reality, Dorsey maintains throughout her writing, and history seems to support her to some extent. Culture aficionados of both the high and pop variety attribute popular Voodoo tropes to the 1929 publication of The Magic Island. The sensationalist travelogue by William Seabrook purportedly chronicled his time in Haiti, his experiences with the religion and, he claimed, zombies. He wrote it during the U.S. military occupation of the country, which, according to scholarship in Duke University’s Black Atlantic project, began in 1915 as an ostensible response to the assassination of the country’s president (American financial and foreign policy interests were also at stake there in the run-up to WWI). The U.S. Marine Corps established martial law on the island, and among its harsh measures was the suppression of the Haitian folk practice of Vodou, which was Anglicized to Voodoo. Once again, the American white Protestant establishment was suspicious of the combination of African religion and Catholicism that existed on the island. Missionaries and journalists conveyed to the American public at home images of a primitive Black population in the thrall of mysterious, dangerous paganism.

In the late 20th century, as America’s late Cold War enthusiasm for science approached the highs of the heady pre-Sputnik 1950s, Voodoo came under a different, more detached, type of scrutiny. When Harvard anthropologist and ethnobiologist Wade Davis announced to much fanfare the findings from his field work in Haiti in the 1980s, he described the process of “zombification” by which victims were poisoned with naturally derived toxins to produce a deathlike state. While it could ultimately be lethal, survivors emerged spontaneously after a few hours.

Davis’ work was inspired in part by that of Zora Neale Hurston, the first Black folklorist to present serious accounts of both New Orleans and Haitian Voodou. Hurston’s work on Haitian Vodou, Tell My Horse, was a blend of personal travelogue, anthropology, and folklore that, while perhaps a more respectful account of contemporary practices than Seabrook’s, nevertheless attracted criticism in academic circles for its impressionistic vignettes featuring Hurston herself as a participant. At one point, by her own account, she boiled a cat alive as part of a ceremony (Dorsey insists that there are a lot of misconceptions around animal sacrifice, which she contends is done more humanely today than in commercial meat-processing). Hurston had started the discussion, however, and paved the way for more sober scholarly consideration of Voodoo’s meaning in the lives of practitioners. For instance, both Davis and Hurston discuss secret societies within the Haitian Vodou system in their work. Hurston wrote about them at some remove, with a mixture of awe and dread, apparently afraid of reprisal, in Davis’ estimation. By contrast, and borrowing from UC Berkeley social anthropologist Michel Laguerre, Davis saw the secret societies as a historical political tool of the formerly enslaved rural classes to assert themselves against a Francophile ruling class. He understood them as extrajudicial protection, meting out justice on behalf of members, with “zombification” functioning as a form of punishment within that system.

Like former President George Bush Sr.’s campaign trail dismissal of supply side economics as “voodoo economics,” or Pat Robertson’s attribution of Haiti’s 7.0 magnitude earthquake in 2010 to the Vodou practiced by rebels during the Revolution, references to Voodoo in America tend to obscure the grievance behind a syncretic religious practice which enabled enslaved Africans to retain their traditional beliefs, and which became a source of solidarity in the face of oppression and suffering.

As with New Orleans itself, outsiders find themselves enticed by Voodoo’s complex cultural mixture. Rarely understood in its religious, historical, or political contexts, Voodoo continues to exercise a powerful hold on the American imagination as something seductive and enigmatic; branding from IPAs to doughnuts indicate that it persists as a countercultural signifier. But in New Orleans, for Lilith Dorsey and others like her, Voodoo remains a powerful source of connection with a community, a way to honor the past, and a means of standing up to injustice.

This story is part of a series Tablet is publishing to promote religious literacy across different religious communities, supported by a grant from the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations.

Maggie Phillips is a freelance writer and former Tablet Journalism Fellow.